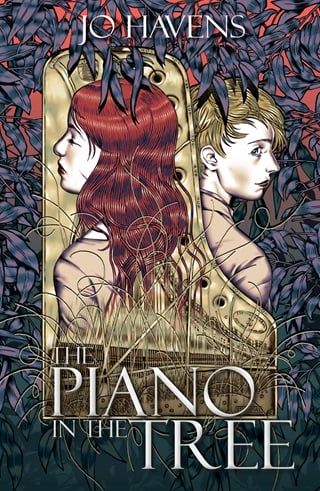

Chapter Five

The first hints of the Southerly didn’t arrive until around six in the evening, but when they did they came in the form of teasing, swirling zephyrs that spun through the thick, hot soup of the summer air. Just an advance guard, at first. Gusts. Eddies. They stirred the leaves on the trees. The wallabies sat up on their back legs, sniffed the air and scratched their bellies. One by one they came out of their hiding spots and slouched down to the dam.

Magpie was the first to notice.

“Here it comes,” she announced. “At long fucking last.”

She threw open the glass doors to the verandah and ignored the howls from everyone else. Polly followed her out.

“You’re letting the cold air out!”

“Come off it, Maggs. It’s still an oven out there.”

Magpie had the binoculars trained on the southern horizon.

There they were. Huge, hulking thunderclouds, still a few hundred kilometres off, but on their way. They were towers of fluffy white cloud, billowing and boiling as they punched up to the limit of the troposphere, pristine against the pitiless blue of the sky. But their fierceness, their promise, was at their base. They hunched on the horizon like an army, a bruise-coloured flank of squalls slowly ripping their way up the coast.

Magpie nodded at them.

“Two hours,” she said, sagely. “There’ll be hail too.”

“Meteorologist now, are you?” Daz grumbled. “Shut the bloody door.”

Magpie dug in. “You people need to harden up. Back in my day we didn’t even have air-conditioners—”

“If you reckon it’s going to be two hours, I’ll make you another jug of strawberry daiquiri.”

She was back inside with the door sealed closed in a second.

“You’re on, darls.”

Polly chuckled and left them to it. The breeze had begun to stir the Steinway in the tree. The wind was still just a breath, only strong enough to set the lowest wires vibrating. A low hum curled around the gentle slope down to the dam and drifted up to the house.

The piano wasn’t visible from this particular spot on the verandah. To see it from the house she’d have to walk right to the northern end of the balcony, skip over to the deck around the hexagon of the study, skirt that and then climb the few steps up to the verandah that wrapped around the bedrooms. It would be a trek across the whole hodge-podge of house extensions and add-ons, so she didn’t. She slipped on her flip-flops and strolled down to the eucalypt at the edge of the dam, wallabies scattering from her path. At the foot of the tree she looked up.

The Steinway was barely a piano anymore.

The wooden parts of the instrument had never made it into the tree. The keys, hammers, wippens and dampers were still in a series of buckets in Polly’s workshop – the eviscera of the music consigned to spare parts. The mahogany ‘furniture’ of the instrument had been irrevocably damaged when Polly had hitched the Steinway Grand up to her tractor years ago and dragged it out of Toks’ house and across the paddocks. She was pretty sure the brass pedal mechanism was still in the west field somewhere and the cows simply nosed around it sniffing out the sweeter grasses. The lid had fallen off when she’d ground the instrument against a gatepost between the two properties. It had sat there for a year, its polish dulling gradually until one day, after a storm, it was gone completely. The legs and the rest of the casing had succumbed to Polly’s axe and she’d burnt the lot in a particularly satisfying bonfire.

But it had always been the metal frame of the piano – the harp-like bit, the plate – that she’d been interested in.

Right now it barely stirred in the breeze. Thick ropes held it above the dam. They looped over a massive bough of the tree, ran through quite a clever system of pulleys, winches and a windlass Polly was particularly proud of, and came to rest at a block near the foot of the tree. It was a system that enabled Polly to lower and retrieve the piano-frame whenever she felt like re-wiring and re-tuning the thing. She rested her hand on the ropes now.

They were humming.

It was a frequency she recognised after years of summer storms and it complemented the tones she was hearing from the piano itself.

It was going to be one hell of a storm.

There was a small jetty of stone out from the edge of the dam into the slightly deeper water. Polly’s father had built it when she was a kid, before they’d had a swimming pool. Tilda and her friends still swam in the dam sometimes, just for something different. It was always colder than the pool on days like this. Sometimes they had banana bed races and squealed about the eels. Sometimes they caught yabbies and Daz cooked them for dinner. Sometimes they fed the ducks and cooed over the rows of ducklings that appeared each spring.

There was an incredible amount of duck poop on the jetty now. Polly gathered up the skirt of her dress and tied a second knot in it. It was more like a mini-skirt now. The wallabies wouldn’t care. They’d seen her scars before. She stepped gingerly between the duck poop and out of her flip-flops. She dipped a toe into the water – warm on top, cooler below, the bottom of the dam just visible between the native water-lilies that peppered the edge. It would be just over knee-deep, she decided, and stepped in completely.

Mud squelched between her toes, cooler than the air conditioning in the house and a thousand times as soothing.

She stood there for a long time listening to the piano as it gradually announced the arrival of the storm and purposely didn’t think about Ksenia Tokarycz.

By the time she returned to the house, Daz had corralled Justin and Tilda into preparing salads and had fired up the barbecue on the kitchen terrace.

Magpie was peering at the approaching storm with her binoculars.

“Um, Poll,” she called. “I think you have a visitor.”

There was a very expensive-looking red Porsche Taycan parked at the top of the drive.

Tilda snapped a pic with her phone. “Who’s that?” she asked. She had a quick look around the room. Both of Jerinja’s current guests were accounted for, still sheltering in the air-con and waiting for dinner. “I think I’d have noticed if one of our guests drove that.”

Tilda was still in her swimming cozzie, too, though the dress she wore over the top was considerably shorter and more revealing than Polly’s. Polly could tell she was debating whether or not the person in the car was worth getting changed for. Polly looked down at her own muddy feet. And her scars. She quickly undid one of the knots in her skirt and it fell to her knees. The other seemed to be stuck. The fabric was damp.

Tilda pulled a face at her. Tilda believed she should own her scars. Polly couldn’t stand watching people try not to stare.

The owner of the car gave neither of them time for anything more.

A woman jumped out, flung the door closed and stormed up the stairs, two at a time.

Polly’s body recognised the woman before her mind did.

She froze. Her heart stopped. Her breath stalled. Her lips fell open.

“It’s—”

The woman didn’t even pause at the front door. She didn’t knock – but then, she never had. Not since they were ten. This woman was as familiar with Jerinja as Polly was. She yanked open the front door as if it was her own.

Once, Polly had hoped it might be.

“It’s—” she tried again. What was wrong with her voice? Tilda was looking at her. Polly was dimly aware of Magpie and Justin hovering in the background, of Richard retreating to the lounge overlooking the pool and taking the two guests with him. She cleared her throat.

“It’s Toks.”

“You shot my horse.”

Of all the things Polly expected Toks to say, that wasn’t it.

Years ago, she’d imagined a whole scenario in her head. In this ridiculous dream, Polly had sucked up her guts and gotten on a plane. She might have just happened to have found herself at a cafe somewhere between Toks’ apartment in Hamburg and the Elbphilharmonie where Toks was Chief Music Director of the Hamburg Philharmonic. It would have been spring. There might have been red geraniums in cheerful pot plants between Polly’s table and the street. And Toks might have just strolled on past.

What an extraordinary coincidence!they’d have laughed, and the years and the resentment and all the bitterness between them would have melted away in a moment.

Toks wouldn’t have changed at all. She would still have looked greedy whenever she glanced at Polly. The scars on Polly’s arms, on her legs, on her face, would have been burnt away by the sunshine and the brightness of the moment and that endless, familiar love in Toks’ smile.

Babe, you look sensational. She’d always felt beautiful in Toks’ eyes. How long has it been?

Toks wasn’t going to say anything like that now. That was just a stupid pile of romantic bullshit that was going around in Polly’s head – bouncing around, clanging, flashing, harsh and violent, like a bullet in an echo chamber. Shorting out her brain because Ksenia Tokarycz was standing in her doorway for the first time in sixteen years and looking just as wild, just as gorgeous as ever.

Babe, you look sensational.

Polly finally managed to breathe again. Toks did look sensational, and it had been way too long.

Ksenia Tokarycz was in skinny jeans as if the forty degree heat meant nothing. They were artfully faded and torn at the knee and she wore a white button down shirt with a pin-stripe so fine it appeared as the softest green. She’d tucked it in at the front – just on one side – and the rest hung out in a ruffled, casual kind of way that managed to look insanely expensive at the same time. She’d been just as casual about the buttons – most were undone, leaving her throat exposed with a good plunge down to her chest. A silver chain hung there – a delicate thing with a tiny pendant that stuck to her skin and moved with her breath. She wore round, silver-rimmed sunglasses with jade-coloured lenses, but these she tore off with one hand and pointed at Polly.

Her eyes were as green as ever.

Polly spared a glance down at her own sundress, a ten-year-old thing made from cheesecloth, for crying out loud. Her fingers were still wrestling with the stupid fucking knot that she couldn’t get undone. Her feet were muddy. That was possibly duck shit. The scars on her arms and legs were a record of her failure.

Babe, you look sensational. How long has it been?

Toks wasn’t ever going to say that to her.

“You killed my horse,” Toks said again, “and shot my farm manager.”

There was an extremely uncomfortable silence.

Polly cleared her throat. Toks was having the same effect on Polly’s body she’d always had. Her heart was racing.

“Why don’t we go through to the music room,” she murmured. She still couldn’t make her voice work properly. “We can talk about it in there.” Polly was painfully aware of Tilda’s eyes flicking between the two of them.

“We can talk about it here.”

Toks put her hands on her hips and her chin up. It was a pose Polly remembered all too well. Toks had been perfecting it since the playground at primary school when the school bully had had a go at her for her European accent and her secondhand shoes.

Filthy Korovinjan refo.

The poor kid probably hadn’t even known what he was saying. None of them knew what ‘refugee’ meant back then. Or where Korovinja was. Not when they were children. Toks had explained it to him, though. In great detail. With her ten-year-old fists and an attitude that had seemed so much older than every other kid in their tiny, country school. It had taken Polly a long time to understand what war meant, what it might have felt like to leave behind your home, all your toys, all your clothes and run, run through the night, run for your life, to the other side of the world.

Toks had always been a little bit dramatic.

And she had an audience now.

Polly sighed and saw her sigh irritate Toks even more.

“Well?”

Justin was suddenly behind Polly. He pressed her shirt into her hand – the soft, white, long-sleeved thing she usually wore in summer to cover the scars on her arms whenever they had new guests. She hadn’t bothered with it today. The current guests had already been with them for a few days and what with the crazy heat… No one cared anyway, as Tilda kept trying to tell her. Polly pulled it on and finally conquered the knot in her skirt. Its hem fell to the floor.

Toks frowned at her.

Polly couldn’t help pulling the shirt a little tighter and Toks’ frown turned into a sneer.

“Hi Toks,” Polly managed.

Toks ignored that.

“There is a woman called Sherry in my house.”

Her voice was clipped and precise, shot through with contempt and barely contained fury.

They were obviously going to do this here, with Toks barely in the front door, Polly hovering like a lost soul in the middle of her own house, and the others retreating to the kitchen bench, their eyes drilling into Polly’s back.

“Kerrie Donovan is your leading hand,” Polly said. Patiently, she thought, impressed at her own ability to sound calm.

The correction shot Toks’ eyebrows up her forehead.

“Sherry.”

“Kerrie.”

Toks’ eyes narrowed. “She was in my house.”

Was?God, had Toks thrown her out? For fuck’s sake.

“She lives there, Toks. She’s been living there for two years.”

“So she said.”

Polly shrugged. This was going nothing like the way she’d thought it might. A bright planter of red geraniums flashed through her mind and she brushed it wistfully away.

“She also said my horses have been sold— No, wait, she said you sold my horses.” Toks jabbed her sunglasses at Polly again. “Aside from the one you shot, of course.”

“I didn’t—” Polly ran her hand up through her hair and instantly regretted it. It was still tangled and full of chlorine from the pool. She probably looked a mess. Toks’ hair was blond – that perfect wheat colour like a field in the sunset, like honey, like gold – and it was in a tousled pixie cut, short on one side, the other tickling her chin. Polly’s fingers twitched. She wanted to run her hands through it, the way she used to.

She clenched her fists.

“You didn’t what? You didn’t shoot my horse? Sherry said—”

“Kerrie.” Polly sucked in a deep breath. “It’s not what you think. Toks, why don’t we go through to the music room and talk about it.” She held out her arm.

“I believe we are talking about it,” Toks said, crisply. She tugged her shoulders tighter and stood taller. Her spare hand, the one still holding the rim of her glasses – fingers taut and long – flicked impatiently at Polly like she was conducting, cueing a recalcitrant brass section, dragging the second violins up to tempo.

Polly bristled. That did it. Suddenly, she was as angry as Toks was.

Outside, she heard the middle register of the piano resonate in a sudden burst of wind. The breeze was getting stronger. The storm was getting closer. In some way, the thought fuelled her. She put her hands on her own hips. One of Toks’ eyebrows twitched.

“I told you about this,” Polly said. “This was two years ago, Toks. I tried to call you. Many times. That bitch of an assistant of yours wouldn’t put me through, so I emailed you. Twice. I explained everything. You said nothing. I could only assume that you didn’t care.”

It rocked Toks’ head back. She blinked, sneered again like there was something sour in her mouth, then ducked her head. Her hair fell across her face.

“Milica was—” She choked.

Polly was surprised. Toks had taken a hit – and early, too. Not like her. Toks started again.

“Milica was my first friend here. Before you. Before anyone. I would have appreciated knowing.”

Her voice was soft and quiet for the first time since she’d burst in. Polly took pity on her.

Milica had been a beautiful old mare – sweet tempered, patient with two young girls who’d taken her on barebacked adventures along the edge of the escarpment and stood, indulgently, as they’d investigated the long-winded and incomprehensible fantasies that filled excitable and imaginative childish minds. Later, Milica had carried the picnic basket as two young women saddled up other horses and trekked down the valley to secret places and lost the whole day there. Milica had been old when Toks’ father had bought her for his young daughter, and Polly and Toks had cared for her and loved her deeply. She’d been family.

“She got caught in a fence,” Polly said, gently.

It had been horrible. It had also been the only time she’d ever tried to contact Toks in the sixteen years since the Incident, but Milica had been important enough to both of them that she’d felt Toks deserved to know.

“Dogs, we think. There’d been a few strays around at the time. Milica had been down in your lower paddock. God knows why. That farm manager you had was a moron.”

Toks’ face closed over. Her lips pressed into a thin line. Polly gave her a moment. Losing Milica had hurt. It had been two years ago for her, but she felt it still. Toks was feeling it for the first time.

Toks apparently didn’t need the moment.

“And?”

Polly blinked. Didn’t she care?

“And I was up in Sydney for a few days.” A Beethoven piano concerto concert series with the orchestra. The piano was tuned between each performance. She always stayed at Richard’s Woolloomooloo apartment when that happened. Not that Toks needed to know that. “Old Willoughby saw her when he was driving past – remember him?”

Toks glared at her. Clearly she did and didn’t care to be reminded. Polly flushed. But Toks had been away for sixteen years. Polly didn’t know what mattered to her anymore.

“Willoughby called me and I called your farm manager and let him know. I expected him to sort it out.”

Polly paused. Bit her own lip. This was the awful part. She didn’t like remembering it herself. It still made her furious. It still broke her heart.

“And?” Toks said, again. She was the coldest thing in the room.

“And he didn’t. Poor Milica stretched that fence for four days, Toks. I’m so sorry. There wasn’t anything to be done.”

Toks eyes slid out of focus. Polly could see the tiny signs that she wasn’t okay with this – the clench of her jaw, the flare of her nostrils – then the tilt of her chin as she tipped her head even higher and pretended it didn’t bother her at all.

So, she was still a stubborn idiot.

The moment stretched out. On the sofa, Tilda sniffed. She’d learnt to ride on Milica too, sitting astride the slow, old darling when she was three years old, her short legs barely making it over the curve of Milica’s back, her chubby fingers tangled in her mane. It had been a terrible time for everyone.

The swift look Toks directed at Tilda was sharp with indignation – who are you to be mourning after my horse? – but when she turned back to Polly her gaze ran thick and slow with venom.

“So you shot her?”

“I’m sorry, Toks. It was the kindest thing to do. The vet was lambing up at Milton Brae. He was hours away.” Polly sniffed too. “I’m so sorry.”

There was silence. Just the hush of the air conditioner and the hum of the approaching storm in the piano in the tree.

“And my farm manager?”

Toks had moved on already. Polly’s own pain at having to euthanise a creature who had been family was obviously inconsequential. It tipped Polly back into irritation.

“He was a dickhead. You’re better off without him,” Polly said, her hands finding their way back to her hips. “Killing Milica was the least of it. He wouldn’t even let your mum onto the property to pick her own peaches, for heaven’s sake. I don’t know where you found him or why you employed him in the first place but he sold off half your herd and—”

“So you shot him too?”

“Oh, for fuck’s sake, Toks, what do you think?” Polly spared at glance at their audience. Tilda’s eyes were popping out of her head.

This was ridiculous. She and Toks were still standing in the middle of the room like prizefighters sizing each other up. Toks’ green eyes were fierce. They demanded a better answer.

“I shot near him. I didn’t hit him. I was angry. Do you think he’d still be around if I’d actually wanted to—”

At the kitchen bench, Justin cleared his throat softly.

Polly took a deep breath.

“He was pretty serious about pressing charges,” Toks said, but her pose had softened slightly. There could have been the tiniest hint of a smile at the corner of her mouth.

“Oh, so you do read your email?”

Toks had the grace to look embarrassed. Just for a moment. She hardened the expression up with a disinterested sneer as soon as she realised Polly had noticed.

“I seem to remember some fuss. I was in Vienna. I had other things on my mind.”

They stared at each other.

“He dropped the charges?” pressed Toks.

Polly didn’t feel like answering that.

“Did he?”

Toks was just as demanding as ever.

Polly sulked. She folded her arms. “He was encouraged not to pursue prosecution,” she muttered.

“Encouraged?”

“Sergeant Simpson is still rather fond of mum’s lilly pilly gin. I make it now.”

Toks laughed. It startled everyone.

“Sergeant Simmo? He’s still around? You bribed the police with homebrew? Ha!” Toks sounded pleased. “Simmo loves me. How many speeding tickets did I manage to talk him out of giving me?”

“Twelve,” Polly answered, without thinking. She hadn’t ever thought that was funny.

Toks looked proud. “Thirteen, I think, if you remember correctly, bab—” She cut herself off, eyes wide.

Polly’s heart stalled.

What had she been about to say?

There was a swirl of wind outside. A splash of frequencies from the piano slammed into Polly’s mind, connected with a thousand memories and threatened to spill over as tears.

“Toks—” she whispered.

Toks put her sunglasses back on.

“Why don’t you stay?” Polly blurted. It sounded desperate. She moderated it. “For dinner, I mean. We’re cooking for eight anyway. One more will be no trouble.” She saw Toks sway slightly, but her eyes were lost behind the glasses. “You’re welcome to stay if you want—”

She was babbling.

Toks’ chin tipped fractionally toward the vast dining table near the windows. It was a hand-hewn thing Polly’s father had made decades ago, rough at the edges, softened by the hundreds of cheerful meals that had been enjoyed around it. Worn smooth by contented bellies and laughter. Right now it was set with bowls of salad, wine glasses and paper serviettes Magpie had folded into a different shape for each diner. Polly saw Toks’ chest rise as she held a breath and decided.

Toks swept a cool assessing look at her audience – Magpie standing with her glass to her lips enjoying the show, Tilda on her knees on the sofa with her eyes like saucers, Daz with his usual good-natured smile, this time loaded with invitation and a cheeky eyebrow at the jug of strawberry daiquiri he’d been holding for the entire performance, and Justin with a cautious expression on his face. Richard was just visible through the doors to the pool lounge, the gentleman sheltering from conflict as he always did. They were Polly’s family. The home and the people she’d been nurturing for years.

It was just about perfect.

One thing could have made it better.

For a tiny second Toks’ lips fell open, then they pressed into a thin line.

“No,” she said, and turned to the door. “Thank you,” she added, like it hurt to grind it out.

“Toks—”

Toks paused with her back to them all. Polly saw her shoulders twitch.

“We buried her under the old quince tree at the bottom of your orchard,” Polly said. “You know, where we used to go when— when— Well, I thought that was a nice place. She liked quinces sometimes, crazy old horse. Remember? I could show you—”

There was a sniff.

Idiot,Polly told herself. It was her property. Toks may have been away for sixteen years but she couldn”t have forgotten that.

“Of course I remember, Pearl Paterson. I’m not the kind to forget.”

She said that like it meant a hundred other things.

Polly winced.

And then Toks went. Down the stairs two at a time to her car. She slammed the door and spun away from the house in a spray of pebbles.

They clattered against Daz’s van.

Her family joined Polly at the windows.

“Well, that couldn’t have gone much worse,” Polly muttered. Tilda slipped up behind her and tucked herself under Polly’s arm.

“If she’s put a dinge in my Kombi—” Daz started.

They were all watching the flash of red between the trees as Toks’ car took the long drive out of the Jerinja property way too fast. She was headed out to the road – a dirt track, really – that led to the only other farm on the escarpment: 613. The Tokarycz property.

Magpie took the jug of daiquiri still held aloft in Daz’s hand and poured herself another glass.

“Daz, mate, point to the part of your Kombi that doesn’t have a ding,” she said, dry as the summer.

And, just like that, the hustle and bustle of a Sunday afternoon barbecue swirled back into motion. Magpie was cunning, in her way. Daz stuck his middle finger up at her and defended his beloved van. Justin laughed, told him he was a ding, and kissed him. That made Tilda groan with mock-disgust and turn back to her phone. Richard emerged from the pool lounge with the two guests. Daz remembered the sausages on the barbecue, squawked with alarm and jogged out to rescue them.

The storm rolled slowly closer. The air lost its dry, merciless heat and began to taste of hail. The piano sang like a harp – the upper register vibrating now like a host of angels on the wind – and Ksenia Tokarycz drove away, as furiously as Polly had always known, in the pit of her stomach, that she would.

“So, that was her, eh?” Magpie had a note of cunning in her voice.

She handed Polly a basket of fluffy white bread rolls and they waited by the table for Daz to finish at the barbecue.

Tilda looked up from her phone.

“That was the famous Maestro Tokarycz. The woman who broke your heart. Your first love. Your one true—”

“Shut up, Magpie.” Polly gave her the kind of smile that said she was right. “Think I was the one who broke her heart, though.”

Magpie snorted. “She’s got one?”

This was the one crucial fact Polly had hidden from Tilda.

“Wait. You two were together?” Tilda’s phone hit the cushions. Forgotten. “When?! Oh my god, Mum! Seriously? You and her—”

“Yes, sweetsticks. Forever ago. At school. At music college.” Polly rolled her eyes at Tilda’s disbelief. “And you can stop looking at me like that, thank you very much. She was my— girlfriend.” She stumbled over the word. It was painful to say it. She’d almost said soulmate. “Girlfriend. Do we still say that these days? Or do the hip young things have a new word for it?”

Tilda looked like someone had just dumped a million bucks in her bank account. “Nope. Girlfriend will do just fine.” She shared a triumphant grin with Magpie. “Way to go though, Mum. Slay. That woman is hot.”

“Oi! Eyes off, please, junior.” Polly wasn’t sure she needed a teenager’s analysis of her failed love life. “Toks is older than me and I’m your mother.” She thought about it for a second. This, at least, was taking her mind off the humiliation of the encounter. She narrowed her eyes. “There is something in your tone, dear child, that suggests surprise— surprise that your mother could pull a woman like that.”

Tilda grinned and backed away with her hands held high in surrender.

“Woah. I was just saying—”

“I wasn’t that bad myself, you know.”

“What? Back in the day?”

“Magpie, smack her for me.”

Magpie was gleeful. The moment devolved into giggles and hugs, the two women – one sixteen, one sixty – knowing just what Polly needed. Polly found herself with a head on each shoulder and arms around her waist. They looked out the window at the storm gathering down the coast.

The men walked in with plates of steak and sausages.

“You’re still alright, Mum,” Tilda said.

Polly snorted. She folded her arms on the table and waited for the potato salad to come her way. Her fingers traced the scars above her elbow. Habit.

“Nice try, kiddo. I still love you.”

Magpie raised her wine glass. A toast. “Girl’s got a point, though,” she drawled. “That woman is definitely hot.”

Polly sighed. “Yeah. She is.”

They were all leaning back from the table in that full, sleepy kind of way when they realised the storm was rolling in faster and more aggressively than Magpie had predicted.

Daz spooned extravagant portions of pavlova into bowls and passed them around the table.

“She’s going to get stuck over there,” Magpie mused. “Kerrie’s always going on about how the causeway floods these days.”

Polly had been thinking that too.

“Who’s going to get stuck?” asked Daz.

“Toks,” Tilda said. She bounced a little in her seat. Still fangirling, despite the ugliness of the earlier scene. “She’s a famous conductor,” Tilda told the two guests and waved her spoon for emphasis. “Grew up with my mum. Lives on the farm next door.” She frowned. “Well, she used to. When she was younger.”

“She’s not old now, darling,” Polly pointed out, mildly. Forty wasn’t old. If it was, her thirty-nine years were getting on a bit too and she didn’t like the thought of that. Besides, Toks wore her four decades well. Very well, she thought, crossing her legs under the table.

“Kerrie won’t be too pleased if she does get stuck there.” Magpie grinned. “Kerrie doesn’t do that kind of pretentious shit. Did you see her sunnies? They were fuckin’ Cartier!”

“Did you see her car?” breathed Tilda. Her eyes narrowed suddenly. “Can you make a lot of money being a conductor?” she asked the table, the dollar signs practically glowing in her eyes.

“Tonnes,” said Richard.

“Really?”

“Ksenia Tokarycz guests for all the top tier orchestras and she has contracts with the Berlin Phil, the Vienna, the New York Phil, and the London Symphony orchestras—” he waved a hand “—just to name a few. The major opera companies around the world clamour for her as well. She can name her fee, and from what I’ve heard, it’s not an inconsiderable one.”

“Like what?” Tilda completely lost interest in the pavlova. Even the others looked curious. Polly was too. She hadn’t considered what an internationally renowned orchestral conductor might take home after a season.

Richard rubbed his hands together. “Well, before coming to Sydney, Maestro Tokarycz was contracted to the Vienna Symphony as Principal Conductor for the last two years. She wouldn’t be doing that for under one-point-five per year.” He shovelled a huge spoonful of pavlova into his mouth and talked around it. “She works for it, mind you, and she’s the face of the orchestra during that time – and given the splashy way she struts around Europe, it’s a stylish face that all the big bands are eager to be seen with.”

Tilda looked blank. “One-point-five?”

“Million,” Richard supplied.

Magpie snorted cream. “Three million bucks? For waving a little stick around?”

“Three million euro,” he clarified. “At least. Because that’s not counting the fact that she’s currently the Principal Guest Conductor of the Berlin and the New York Philharmonics. That means she’s contracted to step in for a short concert series when their Principal shoots off to guest somewhere else. She’ll bring, say, three major works with her and a guest soloist, and they’ll run a short series for a week or two. Maybe eight performances. Then they’ll fly out again. I’ve heard—” and he waggled his eyebrows at Tilda’s enthusiasm “—that she doesn’t walk away from a gig like that without an extra hundred-and-fifty grand in her pocket.”

“Bullshit,” squeaked Tilda.

“And she’ll do that five, six times a year.” Richard sounded gleeful now. He knew full well Tilda was thinking of the thirty dollars per hour she got from conducting the band at the local public school. “Ksenia Tokarycz also has a string of projects going with the Korovinjan State Orchestra. They’re funded by her cousin, of course. Nikoloz Tokarycz is a multi-billionaire, which explains how she gets around Europe in a private plane all the time—” he broke off, suddenly. “Sorry, Polly.”

Polly ignored the way the entire table went still and regarded her cautiously. “Don’t be. It’s alright. Keep going with your story.” She waved off Justin’s sharp look down the table at her too – and the curious glances from the two guests.

Richard started again, more circumspectly now. “Of course, there’s no way the Sydney Symphony is going to be paying her anything like that, which is why she’s negotiated a series of month-long seasons with breaks in between. So she can get back to Europe and keep guesting for the big bucks.”

There was a rather stunned moment of quiet.

“I am so becoming a conductor when I grow up,” vowed Tilda. She pulled her phone out and started scrolling, spooning pavlova into her mouth with half a mind.

“No phones at the table,” chorused Magpie, Daz and Justin together, but Polly shook her head. She knew they’d lost her for now.

Polly leaned back in her chair and pulled her knee up to her chest. So, Toks was gorgeous, successful and filthy rich. The news wasn’t exactly making her feel better.

“How do you know all this, Richard?”

He shrugged. “The whole orchestra has been researching her. Half of us are terrified, the other half are squee-ing worse than Tilda here. She hasn’t guested for us before, but we hear the stories. Maestro Tokarycz doesn’t suffer fools.” He seemed to think about that for a moment. “But her other orchestras practically worship her. I heard the Berlin Phil begged her to become their Principal and she turned them down.”

Polly frowned at that. Berlin had always been Toks’ dream. How many times had she listened to Toks go on about the glass ceiling there and how determined she was to smash it?

“And you’re scared of her?” Magpie looked doubtful. Nothing scared Magpie.

Richard didn’t deny it. “She’s going to work us to death, if nothing else. Nineteen concerts in four weeks. She’s going to drag us through Mahler’s First five times next week and that is not counting rehearsals. Some utterly evil Prokoviev and some Shostakovich. And the contemporary music she’s programmed!” His eyes shot skywards. “The woman is a machine.”

“Well, she won’t be doing it any time soon if she’s stuck over at 613 and the causeway floods,” Magpie pointed out.

A massive crack of thunder made them all jump. The Steinway howled.

It was coming.

They threw open the doors and stepped out onto the verandah to watch the storm approach.

The view down the coast, along the escarpment, was wild. A wall of grey with a rolling, roiling shelf cloud before it was swallowing the small towns and beaches down on the flat. The far end of Thirteen Mile Beach disappeared into the whiteness. Merribee township fell. On the plateau, Nerradja followed. The freeway south, which snaked like a thin silver line through green dairy country, slowed and then stopped. Cars collected under the few overpasses at the exits, then they disappeared into the storm too. By the time Crookhaven was engulfed, the air was freezing, peppered with darts of ice cold water like needles.

The piano sang like a crazed thing in its tree and the party on the verandah inched slowly backwards to the safety of the eaves as the front crept up the hinterland toward them.

The noise, when it hit, was astonishing.

It almost drowned out the piano.

At the extreme last moment, they dashed inside, slamming the full glass doors against the onslaught. Then they gasped at the hail, at the wild, wild wind that tore branches from the trees, at the white-out that hid the entire coast line and turned Jerinja into an island. A raft of friendship and good humour amid the tumult.

Magpie laughed at the expressions on the faces of the two guests.

“City folk, hey? This shit happens all the time down this way in summer. It’s a good excuse for more daiquiris, don’t you think, Daz?”

Polly didn’t have her stamina.

“I’m going to get some sleep,” she announced. She needed to close her eyes and picture Toks again – Babe, you look sensational – and she needed to not be hearing the piano. She kissed Tilda on the top of her head and went.

“In this?” one the guests wondered.

“She doesn’t like the noise,” Tilda explained.

Polly took her pillow to the chaise lounge in the wine cellar. It was the quietest place in the house.

Fullepub

Fullepub