Chapter Four

It took three days for the promised storm to arrive.

In that time, the summer heat dialled itself up significantly. Each morning dawned hot and dry, the sun rising over a still, flat ocean.

Even by the coast, temperatures soared into the 40s. Trees drooped. Wallabies collected by the dam at dawn and dusk and squabbled with each other over the best shady spots during the day. Down in the pastures, the cows beared it stoically. In the town, people gathered in those cafes best known for the strength of their air conditioning, if not their coffee, and by midday the streets were deserted.

Artists, musicians and writers staying at Jerinja drifted up the hill from their cottages and into the shelter of the big house.

And Polly welcomed them in.

The main house at Jerinja was a hodge-podge of styles.

Polly’s parents had been shamelessly herbal. As flower-power children they’d been nuclear-free, save-the-whales, tie-dyed, hippy-dippy tree-hugging greenies and Jerinja was case-study in eco-living long before eco-living was stylish. Her dad had extended the original farmer’s cottage with a string of adventures in home building techniques and an utter disregard for regulations. There were three hexagonal rooms, two on stilts with a stone cellar built beneath them. Timber had been sourced from their own patch of forest on the escarpment. A natural spring had been diverted to provide fresh water to the house complete with a water-wheel that generated power. A history of solar panels ranged across the uneven roof line. A wide deck wrapped around the entire house, punctured in three places by living trees that grew up through it and cast their soothing shade over everything.

Growing up, the house had been the envy of all Polly’s friends. She had a hand-carved rocking horse in the stone-lined bay window. She had a treehouse that climbed five levels into the canopy and that she could access from a rope bridge that began at her bedroom window. The swimming pool was hand-built too, with a waterfall at one end cascading over natural rocks. In the house, an open, airy living space flowed from a generous kitchen through a lounge and dining space, out to the music room, and further to a spacious verandah. The whole thing could be opened or closed against the weather with glass doors that folded away to nothing, and from every room – including the six bedrooms – there was a spectacular view of the coastline.

It was the perfect house for escaping the crazy-hot days, and in its shelter, life slowed.

The visiting writer set herself up in the pool lounge. She typed for a while, got up to slide into the pool, then wrapped a towel around herself and went back to writing. The children’s book illustrator found the study with its old leather chesterfield and its view across the escarpment. He positioned himself perfectly under an air-con vent, put on headphones and got to work.

Daz made everyone snacks then shot off to the beach.

Tilda grumbled about homeschool. No one listened, so she disappeared into her room and did a whole week’s work in one day. She spent the next three lounging by the pool giving the finger to anyone who asked how school was going.

And Polly tuned a piano here or there, travelling straight home afterwards to get out of the heat.

According to the gossip, dutifully reported by Richard via text, Ksenia Tokarycz arrived in Sydney and moved into a fuck-off expensive apartment on the Quay. She was ruffling feathers on the orchestra board already.

Polly carefully didn’t think about her.

Each evening, the little group gathered to eat together in the main house. They clutched gin and tonics and leant on the verandah railing, gazing south down the coast. If a cool-change came – a Southerly Buster – they’d be the first to see it.

On the second day of the heatwave, Polly and Tilda composed music together.

“If you can call it music,” Draga said, that familiar cheek visible over her glass of lilly pilly gin.

She was visiting again – Justin ferried her back and forth several times a week, usually when Daz had something particularly yummy planned for dinner. She was part of the family, after all. It was early afternoon and the heat was intense. Polly wondered if they might be able to get her out of her chair and into the pool, but she expected the woman was far too proud for that.

“Of course it’s music, Mrs T.” With a teenager’s eagerness to be offended, Tilda always mistook Draga’s teasing for irritability. Right now she was lost in the beat of her own composition. “It might not be classical music, but it’s still music.”

Draga snorted. “Sounds like Ravel to me. Not that Ravel would recognise what you’ve done to it, mind.”

“It’s not Ravel!”

Draga looked at Polly. Tilda did too.

“Is it, mum?”

Polly shrugged. She played the phrase she knew Draga was referring to on the nearest keyboard.

“Just a tiny bit. Daphnis et Chloé. Second movement.”

“Ha!” Draga was triumphant.

Tilda looked irritated. “I didn’t know that.”

“I hate what you’ve done to it,” Draga added.

Tilda scrubbed the work back to the beginning and played it through the main speakers. Twice as loud.

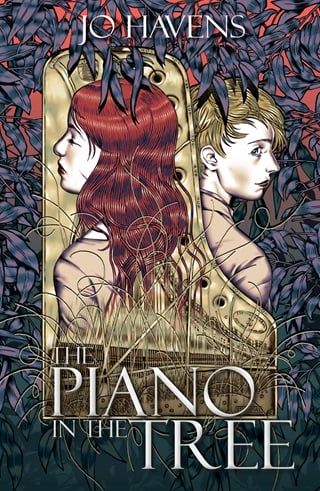

They published their work under the name Tightly Strung. That referred to a few things, of course, but mostly it referenced the pianos. Especially the one in the tree.

It grew from Polly’s wild days, years ago, just after the Incident, when dark, loud clubs hid her scars and the pounding beat kept the memory of other sounds out of her head. She had run back up to Sydney to get away from the baby and from the useless kindness she saw in everyone’s faces whenever they looked at her. She met a woman back then – a DJ – hip and edgy, who mixed music and beats in a style Polly had only ever been vaguely aware of. She taught Polly how to appreciate it properly – from synth-pop through house, trance and techno, all the way to eurowave, trap and acid. And she supplied an endless cocktail of drugs that Polly fell into just as hard. They enhanced the appreciation, Polly insisted to anyone who asked.

She wasn’t sure how long she’d done that shit.

She might have done it forever if she hadn’t run into Daz on the dance floor one night, as smashed as she was, hiding from the same monsters. They’d gaped at each other in a kind of frozen horror while the pretty young things of Sydney’s nightclub scene bumped and grinded around them.

Clueless fools.

The lights strobed like gun flare. The beat ricocheted like bullets.

Justin emerged from the pulsing crowd and stared at them.

Polly saw his lips move, saw a slideshow of expressions snap across his face in the flickering lights.

“Fuck,” he said. “Not again.”

Then he pressed a bottle of water into her hands. He had the same strength in his arms that had saved her the first time they’d met.

After that, all Polly remembered was the sunrise over Bondi Beach where she and Daz had apparently sobbed their guts up for the rest of the night like the two hopelessly broken souls they were, one under each of Justin’s arms. He made her take them home, back to the farm, where her kid was three years old now and her mother’s patience had reached its limit.

It turned out alright in the end.

Tightly Strung emerged much later.

The DJ cared, in her way. She brought a deck and a vintage Roland TB-303 down to the farm.

“You’re musical,” she told Polly. “You have talent. My best tracks are the ones you helped me with. Don’t give it away.”

Justin watched them closely.

“Not for fuckin’ cows, anyway,” the DJ said. Polly could tell the woman had a similar level of contempt for Tilda, who was four now and who had managed to smear mashed avocado onto the woman’s black jeans.

“She got purple hair,” Tilda said, loudly and bluntly. Four-year-olds said it like it was.

The DJ looked unimpressed.

“No like it,” Tilda added.

It was all the recommendation Polly needed. Every relationship had its sweet point and its sunset. Polly didn’t need the drugs and the temptations she knew came with the deal. Now that she had Tilda, Justin and Daz and a plan for Jerinja, she’d find her own way through her mess.

They parted on fair terms and agreed to stay in touch. Polly created samples for her every now and then. Laid down piano or cello tracks for her. The Roland TB-303 sat in the music room and attracted other vintage synthesiser gear like a magnet. A Fairlight sampler, a Yamaha DX7 and an actual 1970s Minimoog, plus a bunch of digital equipment, Pro Tools and a trio of screens.

The recording kit set a dramatic contrast to the broken pianos that Polly collected too. Two uprights huddled in a corner of her music room, both with their innards fully exposed. The harp of a third, utterly disembowelled from its cabinet, leaned against the stone fireplace. A hundred-year old Blüthner grand filled the rest of the room.

Polly tuned and restored pianos for a living.

What spoke to her was the sound of a ruined piano.

When Tilda was ten and sulking over her piano practice, Polly mixed a track for her based on the Mozart she was hating. They added a beat, Tilda’s childish vocals with some naughty lyrics and it made them all laugh. Tilda was ridiculously proud of it, but she turned out to have quite the ear.

Six years later, their collaborations had a far more sophisticated feel. That same ex-girlfriend played one of their tracks at a club in Sydney. A visiting DJ took it back to London and remixed it at the Ministry of Sound, no less. A big name from Berlin loved it and asked for more – and Tightly Strung became a Thing that surprised Polly and Tilda as much as it surprised everyone else.

Spotify was sheer genius.

“It’s bonkers, when you think about it,” Tilda explained patiently to Draga. “We drop a track on Spotify and instantly people all around the world are listening to it.” She bumped her hips against Polly’s. “Perfect for a reclusive weirdo like mum here. Plus: we’re famous!” She grinned.

“Don’t let it go to your head,” snorted Magpie. The older woman was busting a few moves of her own in a small circle directly under the air conditioning. She was in a lurid fuchsia muumuu, her hair twisted up with a paintbrush thrust through it and her feet bare.

Maggs and Tilda always ribbed each other mercilessly, but the heat was making their needling sharper than usual.

“I get paid,” crowed Tilda. She was wearing over-ear headphones, one side pushed back so she could tease Magpie. She tweaked levels as she spoke. “Money! I create music, it goes viral and money ends up in my bank account. How can you possibly rag on that when you make your meagre living scribbling with crayons?”

“Cut it out, you two,” said Polly. “It’s too hot for that. Tilda, let’s tighten up the resonance on this drop-in here.”

Draga shuddered. “I have studied music for longer than both of you have been alive and I don’t even know what that means.”

“It’s called glitch-hop, Mrs T,” called Tilda over the track. “Some circuit bending, some bit-rate reduction, some of mum’s crazy piano samples and some Ravel, apparently. It’s supposed to sound like—”

“It sounds like artificial intelligence discovered religion.”

Polly quite liked that.

Tilda narrowed her eyes. “Is that a compliment?” she asked.

It was all too much for Magpie. “Who cares? Crank it up, darls,” she told Tilda. “I wanna shake my thang then I’m going for a swim. Who’s coming?”

Draga got her own back later that evening.

Richard arrived late in the long summer sunset, after the first days of rehearsal with Maestro Tokarycz.

“She is fucking ruthless,” he declared, falling onto the couch and accepting a gin and tonic from Daz with a limp but grateful smile. “Oh. Hi, Draga. Sorry, but she is. Genius – obviously – but merciless and wholly without compassion.” He groaned. “We’re all knackered. I’ve no idea how we’re going to survive two years with her.”

The air had barely cooled. Daz served up a dinner of quiche, salad and a barbecue chook, and they drained two bottles of sav blanc in the thick, still air on the verandah until the mozzies forced them inside. Richard couldn’t stop talking about Toks.

“She has such depth, such insight,” he gushed. “We absolutely tore Mahler’s First apart today.”

“His first what?” drawled Magpie.

Tilda rolled her eyes.

“We shredded it. Dismantled it. She knew precisely what she wanted, and I swear, I heard things in that symphony that I’ve never heard in it before and I know that work like I know my hands. I mean, it’s Mahler, for fuck’s sake. I’ve done it with the Melbourne and the Singapore.” Richard shook his head, still bewildered. “But she was so— so savage in what she wanted.”

Draga watched him curiously. “What did she want?” she asked, quietly.

Richard was so caught up in wonder he didn’t catch her tone. He waved his wine glass and marvelled. “Perfection!” he said. “And I think she bloody got it too. She stopped us eight bars into the second movement and told us we were ‘playing like Bruckner and Brahms nervously looking forward.’”

Draga snorted.

“But she was right,” Richard insisted. “We needed to pull back on the Viennese schmaltz and let the modernism of the line mock the past, she said. Forget Beethoven! If we continued as we were going we’d be Wagner before lunch.” He grinned at the memory. “Somehow, she made us all laugh at the same time as dismantling everyone’s ego and building a shining tower on the wreckage. She was— she was brilliant.”

It made something inside Polly ache. Of course Toks was brilliant. She always was. But now Richard knew her better than Polly did. He’d known her for a day, maybe two, and he had greater access to her secrets, her talent and her laughter than she did.

It hurt.

It twisted twice as hard when Polly told herself that after sixteen years she didn’t have a right to those things anymore. Sixteen years was enough to change everything. She’d fallen in love with Toks. Maestro Ksenia Tokarycz was a stranger.

Polly drained her wineglass and saw the same bitterness on Draga’s lips. Their eyes met.

“Fetch your instrument, Mr Castelli,” Draga said, suddenly. “Tilda, your violin. Polly, get your cello. Magpie, help me to the piano.”

Tilda and Richard both groaned.

“I’ve had to listen to your doof-doof all day today, young lady. You will play some proper music with me now.”

“I don’t want to—” Tilda whined.

Polly pulled her upright. “Do it, Tilds,” she said, quietly. “I think I need this too.”

Tilda softened immediately.

“Well, I know where the maestro gets it from,” Richard grumbled, but he tuned to the A Draga played on the piano with a smile.

They played a Schumann quartet, elegant and lyrical. It was one they played regularly, Richard and Draga’s musicianship a tutorial for Tilda and a wistful memory for Polly. Polly only ever played her cello when Draga bullied her into it.

The maple wood hummed against her chest, the bouts vibrated against her knees and sent shivers up her thighs. She played with her head bent to the strings, her hair over her eyes and she listened to the hush of rosin, the scrape of horsehair over wire. Ugly, raw ingredients – wood and wire, sap and hair – yet centuries of tradition made them beautiful. The harsh turned sublime.

Too often, if she played at all, Polly saw her worst memories before her eyes. Some days she saw her cello smashed on the stage of a grand concert hall and heard, not the music she was playing, but the shouts of angry men in a language she couldn’t understand. The pleading of her friends. She worked through this every time she picked up a bow. It was a torture she’d endured and worked through over the years as she encouraged her daughter to play, as she joined her in duets from Tilda’s first days on her violin.

It never got easier.

But today, it was different. Today, something else filled her mind. Someone. Today, a love she’d thought she had to forget seemed just that little bit closer.

And the thought of Toks and the music they’d always shared together pushed the nightmares aside and let her truly feel the Schumann as she hadn’t in a long time. She felt it in her skin, in the bone of her chest. In her heart.

Polly wasn’t so foolish that she let it turn into hope.

But it made a nice change.

It was still stiflingly hot once they were done.

“Take me home,” Draga told Justin and Daz at the end of the piece. Her eyes were red.

Tilda noticed. “Are you crying, Mrs T?”

“Perspiring, thank you,” Draga sniffed. “This heat has to break soon, doesn’t it?”

Justin and Daz were deep into the third bottle of wine, so Polly and Magpie drove Draga back to Nerradja Gardens. Polly took the scenic route in the moonlight – the headland above Thirteen Mile Beach. It was a spectacular view even in the darkness. The slightest breath of a breeze blew in over the ocean.

“I think you’re both idiots,” Magpie told them, her eyes on the rising moon. “She’s your daughter and your ex-lover. You have to call her. You have to see her.”

No one said anything.

“Stubborn bloody fools, the pair of you.”

The heatwave stretched into a third day – Saturday – and tempers stretched even thinner.

The water in the swimming pool was tepid by mid morning. The writer, who’d spent the past two days sitting on the side of the pool with her legs in the water and her laptop precariously on her knees, gave up entirely and headed into the forest to the waterfall with a notebook and pen. The water in the glades was always freezing. It sprang from the earth.

In her own cabin, Magpie threw down her paintbrushes with a cry of “fuck this” that was audible across most of the property. She got into her bashed up vintage Torana and disappeared. She was back twenty minutes later with three bags of ice from the local servo, eight punnets of strawberries and a loud order to Daz.

“Frozen daiquiris, my friend. Lots of them.”

She sat herself down on the sofa under the air-con in the main room with a pile of trashy magazines and absolutely no intention of moving for the rest of the day.

Richard fussed over his viola. It was a Brothers Amati instrument formed at the hands of master luthiers in Italy in 1593. Global warming hadn’t been a thing for the Amati boys. Richard packed the viola carefully in its case and came to find Polly with puppy dog eyes.

Polly knew the drill. It happened every summer. Several times. There was a cool, dry space in the wine cellar under the house. Climate-controlled by virtue of being dug half into the ground and built in with stone. Polly’s father had intended it as an enormous energy-free refrigerator. Justin and Daz had taken one look at it and decided it should be a wine cellar.

Once Richard had the Amati fiddle settled in the wine cellar, he was reluctant to leave it behind – as always. The instrument was on loan to him via the orchestra, and was probably worth millions. Richard wouldn’t say how many, but from the way he shook his head when he told the story, it was a lot.

He also had a pile of sheet music with him and his other, cheaper instrument. There was an antique chaise lounge against the stonework. Richard sat down cheerfully.

“Going to get some practice in down here where it’s cool,” he said, and flashed her a grin. “The new boss is a tyrant.”

Polly didn’t miss the distinct shape of a wine glass in his pocket, or his side-eye at one of the new bottles of New Zealand pinot noir on the rack.

She wondered why he hid it. He was welcome to it, he knew he was. But the weather did funny things to people.

Polly spent the day not thinking about Toks.

She spent some time in her workshop. A 1940s Bechstein concert grand discovered legless and upright in a mouldy garage in Sydney’s exclusive Rose Bay was getting a total overhaul. She drilled new holes for hitch pins in the plate – a precision, hair-raising job that required her full attention.

She was a big girl. So was Ksenia Tokarycz. Sixteen years was a long, long time.

Everything came to an end.

Polly would continue to tune the pianos at the Opera House – and wherever else around Sydney her talents were needed – and Toks would conduct the orchestra. And it was highly unlikely their paths would ever cross.

And that was fine.

Fine, Polly told herself as she plucked the phone from her daughter’s fingers, hauled her off the lounge and pushed her, giggling, into the swimming pool. Magpie joined them. They sat on the rocks of the waterfall and sipped Daz’s daiquiris – Tilda putting in a strong argument to try one herself. Daz and Magpie were bad influences.

“Well?” pleaded Tilda.

“A weak one isn’t going to kill her,” said Magpie.

“She’s sixteen,” added Daz. “I spent most of sixteen totally stoned. This has fruit in it.” He held up the jug and waggled his eyebrows.

“Fine,” said Polly. And it was. Really.

Tilda squealed and wrapped Polly in a wet hug. “Love you, mum.”

So, when it finally happened, Polly thought she was prepared.

It turned out she wasn’t.

Fullepub

Fullepub