Chapter Six

She shouldn’t have done that.

“Idiot, idiot, idiot,” she muttered, smacking her palms against the steering wheel. The Porsche beeped at her – a G, one part of her mind registered. She brought the car to a halt out the front of the tired old house she’d grown up in and stared angrily at its front door. After a moment, the door opened and that woman came out. Toks noticed she slammed the screen door behind her with just the right knack to make it catch on the latch.

Toks was surprised she remembered that.

KerrieDonovan stormed down the front steps and stood impatiently next to the driver-side door of Toks’ car. She had a duffel on her shoulder. Toks lowered the window.

“I’m going to the pub,” Kerrie declared, “and then I’m staying at a friend’s place. It’s your house, after all. A bit of warning would have been nice, though.” She waited for Toks to say something, then snorted when Toks didn’t. “I’ve made up the bed in the green room. The one with the old record player.”

Toks’ old bedroom. Toks blew out a swift breath of irritation. This couldn’t get any worse.

Kerrie didn’t see the gesture as gratitude. It wasn’t, even though Toks knew she should be doing better than this.

“Geez.” It was a breath, an outraged oath, and Kerrie looked deeply unimpressed. “This explains bloody everything.” She hitched her bag higher on her shoulder. “So? One night? Two? How long are you staying?”

“I’ll be gone by the morning,” Toks said, crisply. She should go now, actually. If she started driving now, she’d be back up in Sydney by nine, maybe ten. She might still get dinner in one of the restaurants at Circular Quay. She could call Sumi back from whatever it was the woman did in her own time. She could—

She could sit by herself in her empty luxury apartment and stare at the Harbour and not play the piano that hadn’t been delivered yet. Which was why she’d come down here. No performances, no way to work on the ones coming up. She had a Steinway here in her parent’s house.

And there’d been this silly, niggling feeling that she should go home.

Idiot.

“Yeah,” said Kerrie. “Alright then. Fine.”

She turned and strode over to a white Toyota HiLux – the utility vehicle of choice for Aussie tradies and farmers alike – and roared out of the long drive. The truck handled the deep ruts and potholes far better than the Porsche did.

Toks sat and watched until the ute reached the road – a good five minutes, including the time it took for Kerrie to stop the vehicle and close the gates Toks hadn’t bothered to close. A distant roar that could have been ‘selfish fucking bitch’ drifted over the paddocks on the gathering breeze.

There was a storm coming.

Toks got out of the car and looked at her own bag hanging in the back seat – a Montblanc garment bag. Sumi had packed it. She hadn’t decided if she’d stay yet.

The house was as ordinary as she remembered.

It wasn’t rundown. It wasn’t shabby. That Kerrie woman was obviously taking care of it. It was simply a plain, weatherboard cottage built in the 1930s – as functional and uninspiring now as then. It hadn’t even been positioned to take in the view, she thought, climbing the worn wooden steps to the verandah. It enjoyed a practical outlook over a barn that had always housed tractors rather than the cows, and onwards to the milking sheds. If she looked south she could see her mother’s orchard nestled in the crook of a small hill. It sheltered the old fruit trees. It blocked the vista down the coastline.

If she looked north, she could just see Jerinja a mile or two away over the trees.

Jerinja was still magical.

It wasn’t just a house.

Jerinja was still full of people just like she remembered. She’d heard their laughter from the bottom of the stairs. Heard it stop when she walked in.

There had always been people at Jerinja. Polly could never explain exactly who they were. Her parents, of course, but there were always people visiting and working on the farm. Students from around the world who slept on hammocks on the verandah and helped in the orchards or the gardens or at the dairy. Academics and thinkers who talked about alternate methods of agriculture and used words like sustainability and resilient productive ecosystems. They wore hand-knitted sweaters in hand-spun wool, and they created jars and jars and jars of preserves and pickles.

They sat on logs around an open fire pit in the middle of the garden and watched the stars. They played puzzlingly simplistic songs on guitars and ukuleles and everybody sang – and always Toks watched them with bewilderment until Polly grabbed her hand and made her join in.

Dinners were loud, chaotic events around that wonderful table and the Patersons never asked – they simply assumed they were feeding Toks too because she never went home.

They never questioned. They never judged.

Jerinja was always perfect.

Now, it seemed the hippies had gone, but Polly had plainly filled it with friends.

For some reason, that hurt in a way Toks couldn’t quite define.

It hurt to see Polly too.

She shouldn’t have gone.

Kerrie had installed a massive TV where the bookcase used to be and a thoroughly ugly leather reclining lounge where her mother’s wingback chair had been.

One thing about being a stubborn, cold-hearted fool for the past sixteen years was that things stayed the same in your memory, Toks mused. The house didn’t look like hers anymore.

Neither did Polly Paterson.

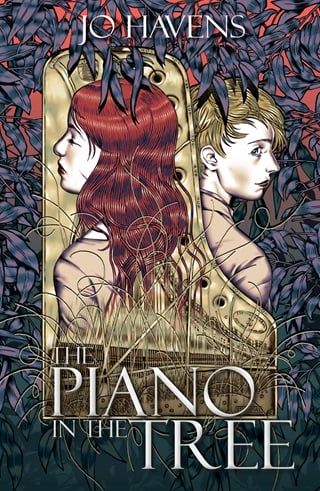

Oh, she was still beautiful. Her eyes still looked at Toks and saw through to her soul. They were still that delicious, warm chocolate colour, liquid like something Toks wanted to fall into. She still had that slim little waist that Toks used to slip her arm around and that perfect fullness to her hips.The curves were different now, riper, but the whole shape of her burned into Toks’ mind the second she saw her.

There you are!There. Like the blush of her skin, the sound of her breath – damn it – the very fragrance of her, right there as the answer to all the questions Toks hadn’t known she’d been asking.

She still had that red hair that flared like the sunset. It still curled its tips to her chin and framed her face like a heart. She still had that adorable pattern of freckles across her nose – like a scattering of quavers and semibreves in a symphony that Toks had memorised years ago.

And her lips. They still held that secret kiss. The one that matched the dimple in her cheek. The kiss that Toks had always tried to steal.

But Polly had changed too.

The red of her hair had burnished to a deep auburn now. The lightest frost was a blossom at her temple. Delicate wrinkles around her eyes were proof of just how easily and delightedly she laughed.

And the freckles were joined by— scars.

Those had been a shock. Toks knew she hadn’t dealt with that well.

There was a sudden rumble of thunder. It took her back to the tram in Vienna and her mother’s early morning phone calls. All those scars, her mother had said, but Toks hadn’t thought— she hadn’t thought there’d be so many. They were on her arms, on her legs. On her face. Everywhere.

Her beautiful Pearl.

Lightning flashed somewhere close just south of the orchard. In the split second of white light, Toks saw Polly’s face again in her mind’s eye.

There was a scar on her face – a single straight line from the apple of her cheek to her jawline. As white and clean and shocking as the lightning. Next to it, just below the corner of her eye, was another – this one perfectly round.

She didn’t want to think about it, she didn’t want to dwell, but a small, dark, deep part of her brain wondered how Polly got scars like that from an accident.

She knew she’d sneered. She hadn’t meant to. She was angry, sure. Fuck, after that ridiculous shouting match with Kerrie, she was furious, but she was angry about a hundred things and had been for years. Most of them were impossible to pin down. Most of them brewed in a tight little knot in the back of her throat and sneering was the only way to stop them from vomiting out. The moment she set eyes on Polly, though, they’d slid down to her stomach and burnt like acid – and stung like hell – and then they were gone. Sixteen years of messy, stupid pride and pain and heartache and blame, and it all dissolved away.

She wasn’t angry at Polly at all.

How could she be?

But then Polly had fussed with that ugly dress she was wearing and that tatty shirt, and she’d folded her arms across her chest as if she hadn’t wanted Toks to even see her.

And that had made Toks boorish and surly. Rude.

Which wasn’t anything new, of course.

Toks sighed.

Typical.

The thunder rumbled again – a sharper crack this time. The storm was getting closer. Toks had forgotten how fast they moved in this part of the world. She should leave, if she was going to go.

But she gave the painfully-familiar-but-strangely-changed living room another glance and realised the thing she’d come for wasn’t there.

Where the hell was her piano?

There should have been two pianos, actually.

There was the old R?nisch upright that she and her brother had learnt on. Polly too once Toks’ mother saw the sense in giving lessons to a select group of kids from their primary school for a little extra cash. It had been a bashed up instrument even then – the best they could afford at the time. Toks didn’t miss the way her mother pressed her lips into a thin line every time she looked at it. They’d had a shiny black grand piano in their drawing room back in Severin, in Korovinja, but Toks barely remembered it.

The R?nisch had been old when it arrived at 613. There were scorch marks on the wood either side of the music stand from the brass candle holders bracketed to the front of the instrument. The burns had freaked Toks out when she was little. They reminded her of bomb blasts.

But Toks had fixed all that when she was nineteen.

She entered the Musica Australis piano competition and smashed her way through the early rounds. Her first performance on the stage of the Sydney Opera House had been the grand final with her mum and Polly Paterson in the audience, both of them more nervous than she had been. Toks had a program of Liszt, Chopin, Rachmaninoff and a contemporary piece, and her eyes on the main prize.

She won them all. Youngest person ever to win the competition, the people’s choice award, best performance of a new work and the opportunity to study under one of the country’s most prestigious soloists.

And a Steinway concert grand.

Polly sat on the verandah and read her reviews aloud as a full team of technicians and piano movers manhandled the magnificent instrument into the lounge room of 613.

“Ksenia Tokarycz is that rare artist who brings profound musicality and prodigious technique organically together,” she read. “Ooo, Toks, listen: ‘Her intelligent virtuosity and total immersion into Rachmaninoff’s idiom showcased a magical ability—’” she blew a short raspberry “—blah blah blah, hang on, ‘natural instinctive quality,’ oh no, this bit: ‘Her powerful yet sensitive interpretation—’”

Toks stuck a pose like a bodybuilder. They’d been swimming in the dam at Jerinja and Toks was in shorts and a slightly muddy T-shirt. Polly dissolved into giggles.

“Stop it, you twit. ‘Her powerful yet sensitive interpretation revealed a one-in-a-million talent as Tokarycz got to the soul of the piece.’”

“Give it a rest, Polly.” That was Mikheil. He’d been there too, down from Sydney where he’d been studying architecture. “Her head is big enough as it is.” He was overseeing the journey of the piano up the front steps like he was already some bigshot designer. “There’s no way this stupid piano is going to fit in our lounge room,” he muttered.

“You live in Surry Hills, Micky,” teased Toks. “It’s hardly your lounge room anymore.”

“It’s not going to fit in my lounge room,” her mother said. She was smoking a cigarette and looking over Polly’s shoulder. She looked grumpy, but then, she always did. Even more so since Toks’ father had passed away. But Toks could tell she was pleased.

“Here it is!” cried Polly. “This is my favourite bit: ‘The applause that followed was endless, and rightly so, for a star had emerged before our eyes.’”

The stars had been in Polly’s eyes that day. She was seventeen and transcendent, and all of Toks’ hopes and desires and dreams and truth were right there in the radiant smile she turned on Toks.

The Steinway was definitely not in the house now. There weren’t too many places to hide a twelve foot long piano.

If her mother or that Kerrie-woman had sold it—

A sudden crack of thunder directly overhead drove Toks’ ears into her skull and a sudden gust of wind slammed the front door shut like a gunshot. A wall of water raced over the hills toward the house. In seconds, it was teeming. Plummeting down. The view to Jerinja disappeared into an angry swirl of grey – even the cowsheds disappeared.

Toks was stuck.

“Just get me out of here,” she snapped.

She had a finger in one ear to block out the roar of hail on the tin roof and her phone pressed to the other. Sumi was being excessively unhelpful and there was the thoroughly irritating sound of happy, relaxed people in the background. Sumi was out somewhere. Enjoying herself.

“You must be joking.”

Toks took a deep breath. “Do I sound like I am joking? Arrange it! Get it done! What are you for, Sumi? Do your job, for fuck’s sake.”

There was a small pause. “Hold on a minute, Maestro.”

Thatwas better. Toks waited.

She stood at the door of her old bedroom, stopped on the threshold as if going in would be an admission of defeat. Nothing had changed in there. Neat racks of vinyl records – all classical. A stack of CDs, as vintage as the records now. A music stand in the corner with some violin repertoire still on it. One entire wall covered with photos of her and Polly.

When Sumi spoke again, it was quieter at her end. The rain still bucketed down outside.

“Is everything okay, Toks? You sound angry.”

“Why didn’t you tell me about my horse?”

She hadn’t meant to say that. It just popped out. She was losing control. She hated this.

“What?”

“You are employed to manage my affairs,” she said, crisply. “I trusted you with my professional and my personal life. I trusted you to—”

“Maestro, where are you?”

Toks hated the careful tone in Sumi’s voice. It tipped her right back into that simmering, impatient fury that had accompanied her ever since she tossed that purple sofa over the balcony in Berlin. She hadn’t realised that had been her normal until a few moments under Polly Paterson’s gaze had stripped it all away.

If it wasn’t pleasant at least it was familiar.

“I’m at home— I’m at 613. Not that it’s my home anymore. There’s a stranger living in it. Apparently she’s my farm manager now. You didn’t think to tell me any of these details? You didn’t think keeping me informed of these kinds of matters might fall under your remit? What the fuck have I been paying you for, Sumi?”

“I—”

“And my horse! You didn’t tell me about my horse!”

She sniffed and pulled herself up short. She was shouting. She was crying.

Toks never cried.

There was a long sigh from the phone.

“It was two years ago,” Sumi said. “You were recording Mahler’s Fifth with the Vienna, you had a two week season with the London Symphony coming up and you were rehearsing Der Rosenkavalier with the Met.” Her voice softened. “I didn’t tell you, Toks, because you always get— well— like this whenever anything about Polly Paterson comes up. And she was the one who had to—”

“I know what she did.”

There was a moment.

“There were some issues with your previous farm manager and the police, too,” said Sumi. “I sorted it all out with Draga and your brother. I didn’t want you stressed. Not with the Mahler. I was trying to— to protect you, Toks.”

“I don’t need your protection. I need you to do your job.”

There was another tight pause. “I was doing my job, Maestro. Your mum assured me Polly Paterson would know what was best for the farm. I left it all in her hands. You don’t even care about the farm.”

“Of course I don’t,” she spat. She’d always hated everything about 613. Except for the fact that it gave her Polly Paterson.

“But I’m sorry I didn’t tell you about your horse. There never seemed to be a good moment. You were back to Vienna after that, and then Gurrelieder with Hamburg. I apologise, Maestro.”

Toks screwed her eyes up and rested her forehead against the door frame. It seemed to be humming with the same frequency of the storm outside. She wandered back to the lounge room and stared out at the tumult. It showed no signs of easing.

“Toks?”

Sumi sounded worried. Concerned. That wouldn’t do. She didn’t want the woman’s sympathy.

She started again.

“It turns out I drove all the way down here for no reason,” Toks said, as coolly as she could. “And now there is a storm. I’m disinclined to drive all the way back again and I have no desire to spend the night in this house that is no longer mine. Please make immediate arrangements to get me back up to Sydney tonight.”

Sumi made an unattractive guffawing noise.

“I beg your pardon?”

“Toks, be reasonable. This isn’t Europe. You don’t have your cousin’s helicopters on speed dial here. I might be able to arrange some other billionaire’s private jet for you but is there even an airfield where you are?”

Toks didn’t answer.

“I’m looking on my phone. There isn’t. You’re thirty kilometres from the nearest airfield— For heaven’s sake, this is your country. Your home. Shouldn’t you be telling me this?”

She was right. Toks wasn’t in the mood to admit it and she was rapidly losing the energy for this particular fight.

“It’s not my home,” she whispered, more out of pigheadedness and habit than anything else. The short visit to Jerinja had made her sick with memories and could-have-beens. Toks owned apartments in cities across Europe and felt at home in none of them. She could still feel the woodgrain of the front door of Jerinja under her palm.

Another blast of thunder shook the house and there was a squawk from Sumi through the phone.

“What the hell—?!”

“Storm,” said Toks. “Go back to whatever you were doing, Sumi. Sorry for disturbing your evening.”

She ended the call before Sumi’s incredulous laugh had the chance to turn into outright mockery.

Toks never apologised.

She found Sherry’s umbrella in the laundry.

It turned inside out in the wind just before she made it to the barn.

“Fuck!”

Rain slammed into her face, individual drops hitting as hard as pebbles. She wrestled the stupid thing right again only to have it snatched out of her hands and blown halfway to Jerinja before she could think. It cartwheeled across the paddocks and was lost to the violence of the storm.

Toks was soaked in seconds.

“Fuck!”

She leant on the door of the barn and tumbled into its shelter. The cacophony inside nearly sent her back out again – the hammering on the tin roof was an assault to her senses, her ears ringing, her mind reeling.

And she only found one of the things she was looking for.

The old upright piano was against the back wall of the old shed. There was an old jerry can on its lid slowly leaking petrol from its seams. A mysterious collection of rusted antique farm equipment was piled at its foot. One of its candle holders was missing but the burn marks were visible even in the gloom.

Toks flipped up the fall board and shrieked as a rat scurried out and jumped to the ground. It blinked at her and ran over her foot. It sped into the darkness.

The Steinway was not in the barn.

She was already wet.

She tried the cowsheds too.

Her piano wasn’t there either.

It was still pouring when she grabbed her garment bag from the back seat of the Porsche. She hugged it to her body and bent double to try to keep the worst of the rain off it.

Of course she tripped on it as she dashed up the verandah stairs.

She had the wit to hurl it toward the front door and out of the wet, but then she simply rolled over on the front step and clutched at her shin.

“Fuck,” she spat. Then she said it again. “Fuck.”

Fuck just about everything.

Toks sat there for a long moment, taking the rain like a beating. She’d behaved like a spoiled child. She deserved this. If she actually had the grace to admit it, she’d been hoping – hoping today might have gone a little differently. Hoping that coming home might have helped her feel something. Anything.

Instead, everything had gone wrong, almost from the beginning.

She should just get in the car and drive back to Sydney.

Her mind ran automatically through her schedule for the next few weeks – the symphonies and concertos programmed for the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, then back to Vienna for a week, Sydney again, then Paris, London and Korovinja. She’d be in Sydney every few weeks. For two years. That was plenty of time if she wanted to try whatever this was again.

She heaved herself upright and shook the rain from her hair like a dog. It was a pointless action, because the moment she reached for her garment bag, the sheer volume of water falling from the sky overwhelmed the gutters. Brown, gritty water sloshed over her like a waterfall. Black, slimy, half-decayed gum leaves stuck to her garment bag like leeches.

She’d just unearthed a hair-dryer in Kerrie’s bathroom and plugged it in when every light in the house pulsed and the power went out.

The rumble of thunder that followed was decidedly mocking.

“Fuck, fuck, fuck.”

An hour later, she was back at the front door of Jerinja.

This time, she knocked.

The man who answered it was fit and muscled. The smile on his face – directed at someone in the house behind him – fell away as he saw her. It was replaced with caution.

He was the same age as her, maybe a bit older. Something about the set of his shoulders screamed military though there was a touch of middle-aged softness to his waist. Toks recognised the same posture in her cousin from Korovinja, though he hadn’t worn a uniform for a long time. She suspected it was the same for this man. The back and sides stayed short, but the blonde mess on top was scruffy and casual.

The hippies had definitely left Jerinja, then.

“Let me guess,” he said, after a moment. “Causeway flooded?”

Toks felt her chin go up.

The rain that fell on the plateau always took one way over the escarpment. At one point between Jerinja and 613, it crashed down a narrow gorge of boulders and settled in a pool between the cliffs and the road. When a storm like this tipped the balance, it spilled over the only road out, cutting 613 off from the rest of the world.

Toks had driven the Porsche through it when it was ankle high. By the time she’d had to turn around and go back, it was thigh deep.

She should have known better.

“And there’s a tree down near old Willoughby’s,” she gritted.

She was trapped on a single stretch of road with no way back and no way forward.

An older woman with a paintbrush through her hair leered at her from behind the man.

“You look like you tried to pull it off the road yourself, darls,” she said.

Toks glared.

“You did? Ha!”

“Shut up, Magpie,” the man said without taking his eyes off Toks. He said it gently, with a kindness that was aimed at her, Toks realised. She hadn’t credited the muscles and the shoulders with such sensitivity. He smiled at her.

She ducked her head. She was misjudging everything today.

“Is Polly—?”

“Polly is sleeping,” the woman said quickly, as if Polly was someone she needed to protect against Toks’ boorishness.

Maybe she was.

But it was only eight o’clock. Toks sneaked a glance at her watch.

“She sleeps when she can.” Magpie – if that was her name – sounded defensive.

The man waved her away.

“I’m Justin,” he said. “Come in. Though if you’re dripping, maybe stay on the mat there. I’ll just grab some keys and we’ll set you up in one of the cabins.”

Cabins?

“I just need somewhere I can change and get dry—”

But he turned her around and led her back down the front stairs, along a path Toks didn’t remember and through gardens that hadn’t been part of the Jerinja she knew. The rain was just a light mist now and the almost-forgotten smell of hail-torn eucalyptus leaves hit the back of Toks’ brain like a drug.

The cabin turned out to be a very elegant tiny home with a handmade quilt on the bed and a vintage record player in the corner. Something in the back of her throat made it hard to swallow.

“I’ll be gone by morning,” Toks said, but Justin cut her off.

“Stay as long as you need to,” he said.

That knowing gentleness was back. How did he know Toks wanted to stay forever?

“Come up to the big house for breakfast.”

Fullepub

Fullepub