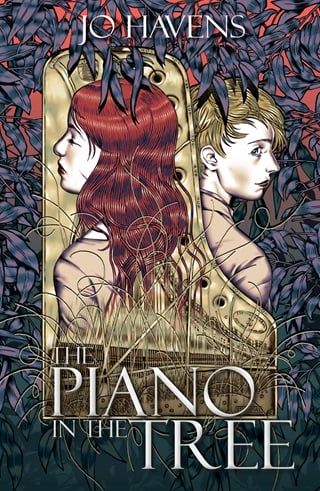

Chapter Thirteen

Polly hauled Toks’ piano down from its tree and restrung it.

It was a mammoth task. It needed the tractor, a winch and a trailer to do it safely but her pulley block system worked well, as it had every time, and Daz came to give her a hand.

“Hardly any wires left in it,” Daz noted. “Geez. Doesn’t make it any lighter.” He grunted. They pushed the trailer through the open double doors of her workshop and attached the piano frame to a chain block. Polly wiped her forehead with the back of her arm. It was March, but it was still hot. She could tell Daz was mostly there to check up on her. “She really pissed you off this time, hey?”

“It’s not that,” Polly admitted. The frame was hanging horizontally in the middle of her shop now. They positioned a herd of metal sawhorses underneath it and let it gently down. Half a tonne of heartache rusting and flaking in the humid air. “It just messed me up a bit. Seeing her again. After all this time.”

“She was nicer than I thought she’d be.”

“Toks is nice!”

That popped out a bit defensively.

Daz looked at her. “Is she? I mean, after the Incident, when she let you spend all that time in hospital in Landstuhl all by yourself and she was just up the road in Berlin—”

“Berlin was hardly just up the road—”

“You spent two weeks there crying to yourself and she never—”

“Ages ago, Daz. Forget about it,” Polly said. She nudged him. Were they really going there? “You were crying too,” she pointed out.

They’d been put in the same ward once Polly had been stabilised. Daz had a bullet wound to the shoulder, but the bulk of the damage had been to his spirit. No one had walked away from the incident in Severin with their equanimity intact. Barely any of them had walked away at all. She and Daz had been two broken Aussies together in a US military hospital in Germany that no one knew quite what to do with.

“I was out of my head, Polls.”

She leaned against his shoulder. Strong, warm and protective, and as messed up as she was.

“Nothing’s changed then.”

He smiled at her fondly. They didn’t unpack these memories too often.

Daz shook himself. Toed at a sawhorse with his boot. “Yeah, well, I figured she was a total bitch back then, but she was alright the week she was here.”

“You only like her because she complimented your venison pie.”

“Mate, that was great pie.”

“Yeah. It was.”

They stood and looked at the piano for a moment. Polly wanted to get into it, into the repetition of stringing, tensioning and tuning. Anything to quiet her mind. She knew Daz worried about her.

“I’m good here, Daz,” she said, gently, gratefully. “If you want to go.”

Daz nodded. He squeezed her arm. “Don’t spend too long by yourself, Poll.”

Magpie checked up on her next.

“Well, obviously you can’t help stupid, but that woman took stubborn idiocy to a new level when she spent a whole week with you actually in the building at the Opera House and still didn’t talk to you.”

Polly blew a huff of breath at her fringe. It had taken a day, but she’d cleared the piano frame of its remaining strings now. The months hanging in the open – from the full summer sun to the sea mist on cold nights – had taken their toll on the pinblock. It was warped and cracked. She was debating replacing it with a whole new one.

“She’s the music director and chief conductor of—”

“She’s an idiot, is what she is! Can’t see past her own ego. I thought as much the moment I saw her.”

Magpie had her hands on her hips, a smear of light blue paint on her cheek and an air of knight-in-shining-armour about her. Polly smiled fondly.

“No, you didn’t. As I recall, you drooled.”

Magpie harrumphed broadly. “I can drool and still recognise an entire bloody field of red flags when I see them. What’s the difference between God and a conductor?”

Polly pulled a face.

“God doesn”t think he’s a conductor.” Magpie looked altogether too pleased with herself.

“You looked that up,” Polly accused.

“What’s the difference between a bull and an orchestra?”

“You don’t have to slag Toks off just to make me feel better, Maggs.”

There was a very long pause. Magpie waggled her eyebrows.

“Oh, for heaven’s sake.” Polly surrendered. “What?”

“A bull has its horns at the front and its arsehole at the back.”

A thoroughly juvenile snort-laugh escaped Polly and Magpie cackled delightedly.

“There you are!” she chortled. “That’s what I like to see. You alright, darls?”

Polly wiped her eyes. She giggled again. “I am. I’m a big girl, you know, though I appreciate what you’re trying to do. I’m fine.”

She wasn’t completely sure that was true. She prodded at her feelings, snipped the weathered, rusting wires from her own heartstrings and decided she and Toks were simply back where they started. Those five days had been a blip. A delightful one, but an aberration nonetheless. One sticky key on an otherwise functioning keyboard, or one perfect note in a tuneless piano? Polly couldn’t decide. She sorted through her supply of wires salvaged from older pianos. Some were carefully rolled. Some were a chaotic tangle.

Not unlike her own thoughts.

Magpie watched her cautiously. “You’re a strong woman, babe,” she grunted. “It will take more than a jumped up, arrogant, fancy-pants maestro from the other side of the world to unsettle you, right?”

“You know that’s true. I’m fine,” Polly insisted. She flapped her hands. “Go. Paint something. You really don’t need to worry about me.”

“But I do, darls. Come here.”

Magpie wasn’t going to drop it until she’d wrapped Polly in a massive, motherly hug and held on just long enough and then some. Polly could smell the turps and linseed oil in her hair, and feel the genuine concern in her arms. She muffled a sniff into Magpie’s neck.

“I heard that,” the woman murmured.

“No, you didn’t,” Polly said.

Richard stuck his nose in a few nights after that.

He arrived with a cheese board and a bottle of red, settled down on one of her high stools and poured them both a glass. Polly put down the tools and joined him. It was late and he’d just driven down from Sydney. The cool air of the first properly autumnal night drifted in through the doors and pooled at their feet.

“It’s a relief to have our associate conductor on the box again,” he chuckled. “Everyone’s blood pressure is back to normal.” He tweaked an eyebrow. “I saw you watching a few performances last week up in the choir seats. What did you think?”

Polly blinked. She’d caught all of Toks’ rehearsals and her concerts that week when she’d been up in Sydney tuning for the Rachmaninoff. She’d tried to stay away, but company rush tickets were only twenty dollars and the only available tickets had been so far from the stage she thought she’d be safe. She didn’t think anyone had noticed.

“Of Yajing Tan? And the Rachmaninoff? She was amazing. You guys absolutely nailed the symphony.”

Richard tapped his glass against hers. “Not what I meant and you know it.”

Polly sighed. “Toks was incredible. I couldn’t take my eyes off her.”

“Ha! Neither could we. She’d have eviscerated anyone who did. She has the most extraordinary style and I’m quickly becoming addicted to it.” Richard grimaced. “Just like a drug. Beautiful and brutal. I think we all love her and hate her in equal measures.”

That sounded familiar to Polly.

“Have you seen what she’s up to in Europe?” Richard asked mildly, but there was something sly in his tone that made Polly look again.

“Why are you asking?”

Richard’s hand landed on her knee and he gave it a squeeze. “It’s not as dark up in those cheap seats as you think it is, dearest one. I saw your tears.” He tipped his head toward the house, where everyone else in their odd little family was sleeping. “The others are talking you up and making sure you’re still okay on your own, but I wonder if you need to be. On your own, that is.”

There was a moment and the evening ticked with the noises of the night – crickets in the bushes, a boobook in the trees overhead, and an orchestra of pobblebonks down at the dam.

Polly hadn’t ever imagined she’d be on her own. That was part of what had made Toks’ rejection so painful – ever since she was seven, she’d simply known with her soul that her life would be with Toks. Watching Toks during rehearsal had been difficult. She’d crept into a box behind the cellos and basses, high up at the back, silent in the dark. Polly had been entranced by her dishevelled elegance as she led the rehearsal, her sleeves rolled to slightly different lengths on her arms, her golden-blond hair tumbling into her eyes then impatiently brushed away.

It had made Polly’s fingers twitch.

In performance, Toks had been extraordinary.

And that had revealed the gaping hole in Polly’s life – not just the place where Toks belonged, but where her own ambitions had withered and died too. She’d told herself over the years that tuning pianos and pasting together some boppy tunes with her daughter was enough. She’d convinced herself she was content. She’d held her own dreams under, struggling against her hands, until they’d slipped quietly away and left her alone, the music bleeding from her fingers with every passing day. She’d devoted herself to supporting the art of others instead.

Seeing Toks right there in the spotlight having achieved all the things they’d planned together hurt like hell.

But she’d observed enough of Toks that week at the House to know that Toks was suffering too. Toks put on a good face, she strode through her life with confidence and style, but Polly knew her. Most of that towering arrogance was swagger. Her aloof and accomplished maestro performance was a shield. Toks was alone too.

Polly sighed. The whole thing was ridiculous. She’d lost her dreams and gained a daughter and a bunch of loveable busybodies who’d become her family. Toks glittered on the absolute pinnacle of achievement and had no one.

Polly pulled a face at the loveable busybody in front of her now. “Maybe I was crying at the music,” she tried.

Richard snorted. “Maybe you weren’t.”

“Yeah,” she admitted. “Maybe I was crying for a million might-have-beens and too-late-nows.”

“Never say that, my dear. That night when the maestro was here and she made us all play together? That was the best I’ve heard you play in a long time. You two must have really been something together. Don’t pretend it’s all gone, Polly. The music is still in your heart. I strongly suspect someone else is too.”

She nodded. She couldn’t deny that.

Richard stole the last piece of cheese from the platter, stood up and stretched.

“And on that note,” he declared. He gave Polly a keen look suffused with a care and concern that almost made up for all things she’d relinquished. “Are you sleeping?”

“Not yet,” she said. “I’ve re-strung. I’m starting on the tensioning now.”

Tensioning an entire concert grand piano from nothing was a curious business – a blend of brute force, delicate precision and howling atonalities all in pursuit of eventual harmony.

Brute force was needed to convert the tensile strength of more than two-hundred-and-thirty wires to melody. Nearly a third of them were copper-wound steel, the lowest ones as thick as Polly’s pinky. Delicate precision came not with the actual tuning, but with the introduction of nearly thirty tonnes of pressure to a cast iron frame in a careful, methodical way that didn’t cause the whole harp to buckle and buck like a wild animal.

The noises it made as she pulled each wire closer to its eventual tension upset almost all animals within earshot, so Polly worked at night. At midnight. At three a.m. when the familiar, ceaseless nightmares drove her sweating and shaking from sleep as they did every time she closed her eyes.

The ring-tailed possum in the tree above her workshop growled and howled back at her, and when it jumped down from the branches onto the tin roof with a thud that scared the hell out of her, she took a break.

What was Toks doing in Europe?

She started on her webpage and saw a four week programme of concerts across five cities and four countries that was breathtaking in its scope. Prestigious performances in Paris, Lyon and Geneva. All four epic operas of the Ring Cycle in concert form scattered over eight nights in Hamburg. In the final week, she was in Korovinja for a national celebration playing a programme of the country’s greatest musicians with Severin Philharmonic.

Right now, the maestro’s social media showed her part way through the Ring Cycle – action shots of her at the podium, her hands ordering and cajoling brilliance from a hundred musicians. Garlands of flowers decorated the floor at her podium. Group pictures of Toks with a dazzling array of famous opera singers leapt out of her feed, her arm over the shoulders of the men or slipped around the waist of the women.

A candid shot of Toks frowning over an open score of music on a plane somewhere, a pencil in her hand.

An interview in two languages in the maestro’s dressing room at the Elbphilharmonie, a magnificent view over the Elbe River in the background.

Toks looked tired. In the interview she mentioned a whole raft of exciting projects to come, including something new and exciting in Australia.

It was too much for Polly. She put her phone face down on her work bench and picked up her tuning hammer again.

The possum screeched at her.

Polly was three weeks into re-stringing the remains of Toks’ piano when Tilda came belting into her workshop one afternoon with Polly’s phone in her hand and indignation in her tone. Justin was right behind her.

“Mum! You have a message. You have three! You have three messages!”

“Tilda, she doesn’t have to look at them if she doesn’t want to.”

“Of course she wants to look at them. That’s what messages are for. That’s what you do with messages. I don’t even understand how you can leave your phone in the house when you’re working out here. Boomers and tech, honestly!”

Justin swatted her.

“What?” Tilda held the phone out to Polly with one hand on her hip and a belligerent glare for both of them.

“Nobody here is a Boomer, Gen Z, and you know it, so you can drop the attitude,” Justin told her.

“Just look at your messages, Mum. Please?”

Polly took her phone. There were three notifications from a number that didn’t have a name associated with it. The plus code at the beginning suggested they were from Europe. One had images attached.

They could only be from Toks.

A tornado of butterflies flew straight through Polly’s chest. They punched through her front, disintegrated her heart, picked the pieces up on their wings and tore out between her shoulder blades, back into the open, pitching themselves at the sky and the blazing sun.

She took a breath to recover. Justin watched her cautiously.

“You don’t have to look,” he said, quietly. “I can block her number, if you want. You won’t even have to see them.”

“Why would she want to do that?” Tilda looked at Justin like he was insane. “Come on, Mum.” She jiggled. “Pleeeease?”

Her impatience made Polly suspicious. “How does Toks have my number?”

“Just read them.”

“Tilda?”

“Please?”

The mother-daughter guilt-thread tugged irresistibly. Polly thumbed at her phone.

— Early thoughts —the first message read. — This on the plane, so will need some revision. What you two have done to the allegro theme – transposing to g major, you are literally killing me – really hurts my soul, but I feel this has potential. Very interested to know what you both think —

Polly flicked straight to the attached images. There were ten.

They were all photos of an orchestral score, large sheets of paper spread out on a table, a tumbler of whiskey on the rocks just visible at the edges. Twelve staves of handwritten music scrawled in Toks’ almost illegible style, though Polly would have recognised it anywhere. When she zoomed in, she saw it was one of their tracks – Tightly Strung – the track that had first launched them to fame. A massacred snippet of Beethoven’s Seventh and some lyrics about love, and the song they’d all danced to in the big house only a month ago, Toks moving like she was made of music, Polly not knowing where to look and Magpie laughing at them all.

Toks had begun to score the electronic version for orchestra.

Polly held up the phone for Tilda to see and the gleeful happy dance the kid did told her everything she needed to know.

“Oh my god, she’s really doing it!” Tilda squealed. “Maestro Ksenia-fucking-Tokarycz is scoring our songs!”

Justin smacked her head. “Language.”

“Fuck, yeah!” Tilda sang.

Polly looked at the third message.

— Really interested to know what *you* think, Pearl, about a lot of things. I’m sorry about how things turned out between us these last few weeks. Can we talk? Please? —

Polly had to sit down. ‘Sorry’ and ‘please’ from Toks all in the same message? She was reeling.

“What is it?” Justin asked. He was still worried.

Tilda was still buzzing. “Can I have another look? Can you send them to my phone?” She seized both devices and did just that. “Oh my god, she’s written it all by hand. And on a plane?” She looked a question at Polly, astonished. “She just wrote it down? Straight out of her head? For an entire orchestra? By hand?”

Polly huffed a smile. It was exactly the kind of cocky brilliance Toks was famous for – writing out a symphony as easily as if it was a shopping list. The hole in her chest flooded with warmth.

“You’ve got a lot to learn, kiddo,” she murmured. Tilda was scrolling through the pics of the score with a dazed look in her eyes. “But I get the feeling you knew she was doing this. You want to tell me why?”

“She asked me, Mum. Well, her assistant did. She’s super keen about the Synthphonic Sessions, and I’m half of Tightly Strung, after all. It’s my call too.” She looked between Polly and Justin and jiggled on the spot again. “Please? It will be so cool.”

Her daughter made a fair point, Polly supposed, but the words that were spinning around in her mind were still the ones from Toks.

Could they talk?

Please.

She knew how much a request like that would have cost Toks. She wished it had come sixteen years ago, but suddenly the strings inside her own chest were vibrating as taut as the wires on the piano frame in front of her. She knew she’d take what she could get.

“Okay,” she said.

“Wooo!” Tilda’s whoop startled all of them. She danced out of the workshop singing the lyric from the track at the top of her lungs.

Justin ducked his head to get a proper look in Polly’s eyes. “You sure? You okay?” he asked.

She understood his hesitation. He’d been looking after her for so long. She smiled and nodded slowly. She wasn’t, but it was worth a try.

“Yeah,” she murmured. “I’m fine.”

Polly finished restringing the piano and hung it back in the tree.

For some reason, she didn’t feel like shooting at it.

In the evening breeze, every note sang strong and true, billowing out like a promise.

Fullepub

Fullepub