Chapter Twelve

At least Sumi was pleased to see her.

Toks knew that was only because Sumi took one look at her face when she got back to Sydney, made a very good guess and suggested they christen Toks’ incredible apartment as a consolation prize. Toks also suspected it was because Sumi was already sick of the five-star hotel she’d engaged for herself uptown.

Toks’ mood couldn’t have been worse, but Sumi’s dress fell to the floor and she draped herself very prettily over the lid of the Steinway concert grand that had finally been delivered.

Who was Toks to say no to an offer like that?

It wasn’t like there was anyone else in her life.

Fucking her assistant while staring at a magnificent view of the Harbour, the Bridge and the Opera House did nothing to move the needle on the contempt Toks held herself in. She’d been a fool. A naive, simpering fool, and she couldn’t believe she’d let down her careful walls in just five short days.

Five wonderful days.

She should never have gone home— fuck it, she shouldn’t even call it ‘home’. She hadn’t for ages. She’d written that shit off sixteen years ago. Drawn a line under it. Packed away her heart. It had hurt to do it then, but Toks was reeling at how much it stung right now.

Oh, but she’d nearly been lured in again. Polly-fucking-Paterson and that cheeky smile Toks had thought was meant for her. Her lips, her eyes, that pretty flutter her lashes made when she looked shyly down and back up again. Her shape, her hips, and her waist that still made Toks’ palms tingle. Her breasts that stopped Toks’ mind and had her licking her lips and letting her eyes slip downwards. Remembering Polly’s scent, her taste, her surrender – fuck, the whole essence of her that still cried out to Toks like a symphony, a song in her soul that she couldn’t ignore—

“You okay, Toks?”

“I’m fine.”

“Your hands seem a little heavier than usual.” Sumi looked back at her over her shoulder and Toks hated both of them.

“I thought you liked it like that.”

Sumi frowned. “You know I do.”

A ferry down in the Harbour blew its horn. F sharp. Something threatened to crumple the scant control Toks had on her expression. Threatened to avalanche lower and twist in her chest and gut too.

“Bedroom,” she ordered.

Sumi watched her for one moment longer, then grinned and skipped away. Toks stepped between unpacked boxes of music scores and suitcases to get to a bedroom with an equally sensational view.

It was the finest view over one of the most beautiful cities in the world, but it had nothing on the view from Jerinja.

“Rough time down home?” Sumi asked, when Toks slapped her back into action a while later. Sumi would spend her life on her back if Toks let her. She settled down between Toks’ legs.

“Do I look like I want to talk about it?”

“Normal people talk about their feelings.”

Toks held up her hand. “Perhaps. But you could be doing something far more useful with your mouth right now.”

Sumi pulled a face. “I suppose it was too much to hope that going home might make you a better person, Maestro.”

Toks didn’t even know where home was. Once she’d thought it would be wherever Polly Paterson was, and that shitty attic apartment in Berlin all those years ago that she’d nested full of treasures she couldn’t wait to share had been the last time she’d ever attempted to make one. She felt sick when she thought of it – and her naivety. Polly had been fucking some Korovinjan dude while Toks had been stupidly tending a row of potted herbs on a window ledge for her.

The cruelty of it hollowed out her belly and stuck in her throat like a rock.

She sobbed.

Sumi looked at her strangely.

“Don’t stop,” Toks snapped.

But Polly had scars, one tiny part of her mind whispered. Polly had been hurt. There had been an accident and she couldn’t—

She couldn’t be bothered letting Toks know where she was because she’d been screwing someone else. A man. And then raising his child.

The fact that Toks had screwed – and was now currently screwing – any woman keen to open her legs for her wasn’t lost on Toks at all.

She’d made a life from it. Five days on a farm with a friend she’d known at school needn’t change that. Toks was the best in the world at what she did. She didn’t need Polly Paterson.

“I don’t think this is working,” Sumi muttered. She wiped her chin with the back of her hand.

Toks sneered. Untangled her fingers from Sumi’s hair. “You should go.” She strode away to the shower. Did she even pack a robe?

“Toks, are you sure you’re okay?”

“Just go, Sumi. I have work to do.”

She looked pretty, all confused and worried and pulling her clothes on and hopping on one foot, but Toks didn’t want to think about her care. She had the awful feeling she didn’t deserve it.

It made her callous.

“I’ll see you at work tomorrow morning.”

“At least come and get some dinner with me, Maestro. There’s a Japanese place just down here on the Quay I’d like to try.”

But Toks waved her away and Sumi was so concerned she didn’t even have a smart-arsed retort for her. Toks wouldn’t let herself miss the big table at Jerinja and the easy laughter around it. She wouldn’t think about Polly Paterson’s sweet smile like the home her soul longed for.

She wouldn’t.

She showered, then padded around her echoing apartment not seeing the view. She dug the score of a symphony out of a box and lifted the fall board of the instrument.

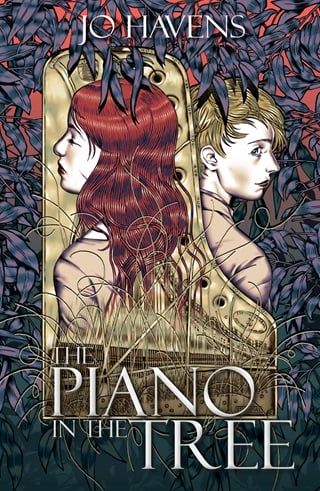

Perfectly shining pianos standing like monuments in empty apartments were Toks’ own special kind of loneliness.

The air conditioning vent in her office hummed in E flat.

The Sydney Opera House was an extraordinary building but the maestro’s office was distinctly less opulent than the ones she was accustomed to in Europe’s finest concert halls. Granted, it was the only room assigned to creatives that actually had a view but Toks couldn’t keep uncharitable thoughts about Australia’s bloody egalitarianism out of her mind. The staff were lovely, every demand on her rider had been met and the coffee was excellent, but Toks was already looking forward to the end of this three week season.

That fucking air-con vent was going to drive her insane.

There was a Yamaha baby grand jammed into the limited space between her desk and a sofa, and it bore the marks and coffee circles of all the hundreds of maestros before her. It played nicely enough – for a practice, reference instrument – but Toks was in a mood. Snapping at the staff only made her feel slightly better.

“Get this tuned.”

The team member’s eyes widened and shot a quick look at Sumi over Toks’ shoulder. Toks didn’t need to turn around to know Sumi was rolling her eyes behind her back, apologising for her attitude without words and making friends where Toks could not. Sumi was establishing herself as the reasonable one – the go-to person who could manage the rock-star maestro’s moods.

It was their usual pattern, but fuck that too.

“Don’t look at her. I gave you the order. Get it tuned.” She had to go. She had a four hour rehearsal to lead. Four hours of Mahler’s First and some contemporary Australian music she’d commissioned. And an orchestra she didn’t know. She hitched her best arrogant sneer onto her face. “And fix the air conditioning vent. It is unacceptable.”

She heard the staff member’s puzzled whisper to Sumi as she left.

“What’s wrong with the air conditioning?”

Sumi’s easy, friendly laugh was physically painful.

Oh, she could turn it on when she had to.

She was the best in the world for a reason. Musicians loved her for the collaborative tone she took with them, drawing their utmost from them and making them feel as if they’d created something extraordinary together. She softened her orders with jokes and shared the finer points of her vision with them. She worked them hard, insisting on precision, bending them to the subtleties and nuance she demanded. She saw the exhausted side-eyes they gave each other but also the smiles as they knew they’d achieved something exquisite.

She made sure they were grateful to have her.

Richard Castelli sat almost directly in front of her – leader of the viola section – and a difficult reminder of a handful of the loveliest days she’d had in a long time. He was good – of course he was – but she could hear Jerinja in the scrape of his bow, the majesty of the escarpment in his tone.

The memory of a duet with Polly at her side.

She tried not to look at him.

She charmed the orchestra and she schmoozed its sponsors. A lunchtime meeting with executives and management in a glittering tower high above the city, and she was just as dazzling. They laughed at her quips, keen to shake her hand and shower her with compliments. She played the part of the humble musician and ignored the mocking looks Sumi aimed at her when the elites weren’t looking. Back at the House, a publicity photoshoot was an irritating necessity, as were a few interviews for social media, but she vetted the results with a playful air that made everyone adore her all the while ensuring they delivered exactly what she wanted.

Her concertmaster and heads of sections met with her next, all suitably honoured to be meeting her at all, all intelligent and capable musicians and likeable humans. She played the appropriate role for them too, nurturing the team she’d have to work with over the next two years, building relationships and learning the strengths of her new orchestra. Richard was quiet. She gave him a tight smile.

A few quick moments in her office before her evening appointments revealed the air vent was still humming in E flat and her piano had not yet been tuned.

She would never have tolerated substandard bullshit like that in Berlin, Vienna, Hamburg or Severin.

It won Sumi a serve from the sharp edge of her tongue and, as a direct and stupid consequence, a take-out dinner alone in her empty apartment.

She shook that off. Her soloist for the second week’s programme, the deliciously obedient Rebecca, buzzed her apartment door not long after.

Rebecca was very impressed with the view too, not that she saw much of it, with her face pressed into the furniture.

Toks tore shreds off Sumi the next morning when the air vent continued its irritating hum.

“It’s a building-wide air conditioning system, Toks. Be reasonable.”

Sumi was lucky no one from the House was within earshot.

“It’s a constant E flat – no, fuck it, it’s a good three cents off a perfect E flat and it is doing my head in. I’m trying to work here! The first movement of the Mahler is in D, the second is in A!” Sumi did not look suitably concerned. “What key is the third movement in, Sumi?”

Sumi blew out a sigh.

“Well?”

“D minor,” she admitted.

“And the fourth?” Toks couldn’t believe no one else could feel her pain.

“Yeah, okay. F minor.” Sumi grimaced. “That sucks.”

“Finally!” exploded Toks. “Get it fucking fixed, or you can crawl into the air vent yourself.”

“Come off it, Toks.”

“You will address me as Maestro while we’re at work.”

“Your piano has been tuned, if your royal highness might like to inspect it. Perhaps it might lift your mood.”

“Get out, Sumi.”

“Gladly.”

The piano was perfect.

In fact, as much as it pissed Toks off to admit, the piano was beyond perfect. It hadn’t simply been tuned, it had been re-voiced to suit the dynamics of the room. Every key had been meticulously re-weighted and the battered instrument was now an absolute dream to play.

For a second, she thought of the liquid, fluid sounds that spilled from the ruined pianos around Jerinja, but she banished that frivolousness. She didn’t have time for nonsense like that.

Someone had worked hard overnight.

Toks shrugged and dropped the fall board with a thud. It was her due, of course, as the generation’s finest conductor. By far and away the most prestigious musician to grace the Sydney stage.

The noise made Sumi pop her head through the door.

“Well?”

Toks hummed. E flat. Curled one side of her lips in a fuck-you smile.

“I forgot to mention, Maestro, but your mum called.”

“No,” Toks said, flatly.

“No, what?”

“No to whatever it is she wants. I have a rehearsal. You sort it out.”

She dragged the orchestra through the intricacies of the fourth movement of the Mahler, and tried to ignore the obscure feeling of longing that twisted in her gut.

Of course, her first week reviews were excellent.

Sydney audiences loved her, leapt to their feet and called her back to the stage over and again. She tried to sweep their adoration aside and refocus it on the orchestra, but the crowds were rapturous. Pleased and proud to have their home girl back in Australia. She flicked her fingers at the band and gave the audiences an encore or two. Mahler’s Blumine and the Adagietto from the Fifth, and knew she’d won their hearts forever. The orchestra had been… satisfactory, and she endured their congratulations. Even offered a few in return.

Their success only meant another round of sponsorship and executive meetings, with the dubious added pleasure of the suits being rather smug and self-congratulatory. There were some television and radio interviews for various art programmes, some guest lecturing at the Conservatorium and the Sydney universities – and, of course, continuing rehearsals.

The pattern was endless. Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday to get three hours of new and complex music under their belts. Performances on Thursday, Friday and Saturday.

Busy days. Intensely focused evenings.

Empty, lonely nights.

Toks was used to it.

The second week of her Sydney season was devoted to the Tchaikovsky violin concerto with Rebecca Herzog. Toks spent the mornings extracting precisely what she wanted from the orchestra, and in the evenings, she worked with Rebecca more… personally. But in the afternoons, she moved on to preparation for the third week of the season – meeting and rehearsing the soloist for her piano concertos.

Yajing Tan arrived from Philadelphia with two hours of Rachmaninoff in her fingers – the third concerto and Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini – both guaranteed crowd-pleasers. The soloist herself was a dull creature with an equally serious husband who followed her around the world as her assistant and translator, but her talent was remarkable.

She arrived at the Opera House to select a piano.

There were a myriad of considerations involved in selecting an instrument for a piano concerto with an artist of Yajing Tan’s calibre and with Rachmaninoff on the programme. The Sydney Opera House was a Steinway venue and had six model D concert grands in its performing piano bank, which, as Sumi pointed out, was convenient because Yajing was a Steinway artist just as Rachmaninoff had been. Not that Toks cared. If the best instrument for the work had been a B?sendorfer, she would have insisted a selection be made available and the House would have complied.

The six instruments available for them to choose from were always maintained in impeccable condition and stored below the stage in a climate controlled environment matching the auditorium as closely as possible.

But all the same, pianos were complex and delicate beasts, each with their own particularities – a deeper tonal richness here, a more powerful dynamic range there. Each had a touch, tone and responsiveness that called to a performer’s personal artistic expression, or more perfectly aligned with the repertoire. Toks had her own requirements for the piano she’d be leading through the concerto, but collaborating with the artist on the decision was where the art began.

She ordered all six instruments be tuned and brought to the stage of the concert hall so that she and Yajing could audition them and hear them in the space. The process of choosing a piano would take an hour at least, and Yajing would play the same fragments of music over and over. Once they’d chosen, Toks would order the technician to make the necessary fine adjustments to the action and voicing so that the instrument would respond as precisely as possible to her and the soloist’s expectations.

As Toks strode through the side doors to the stage with Sumi, a representative from the Opera House, and Yajing and her husband in tow, the very last person she expected to see was Polly Paterson.

“That’s Polly Paterson?” Sumi muttered, under cover of Yajing bashing her way through the ossia cadenza on one piano after another. “Not what I expected.”

“I don’t want her here.” There was a second while Toks’ brain caught up to her mood. “What is that supposed to mean?’

“She’s the chief piano technician for the House. She’s here to serve your final choice and voice the instrument to your requirements. I can’t send her away. You’ll need her.”

Polly had retreated to the prompt side corner and was whispering with the stage manager. It looked chatty and friendly. As a mech walked by and plainly cracked a joke, both women pretended outrage and mock-thumped him, one arm each. Polly was obviously comfortable in a space that seemed to be hers. She took something from the ever-present prompt-side lolly jar without even thinking about it.

Polly Paterson was more at home here than the damned maestro was.

She kept her eyes low when she looked to the stage, though. Her gaze met Toks’ once, then fluttered back to the floor. She looked willowy and fresh in tailored green flowing pants and a floral shirt. That glorious titian hair that Toks used to twist her fingers in was an efficient ponytail flipped forward over one shoulder. She stood out like a rose amid the plain blacks of the rest of the crew.

Toks could almost smell the sea breeze against the escarpment and the tang of eucalyptus in the air.

But she seethed as Sumi turned and gave Polly a smile and a friendly wave. “What do you mean, she’s not what you expected?” Not that it mattered. Why was she feeling protective? And of what? Sixteen years of rejection?

“You’ve never said, Toks, but that woman broke your heart, didn’t she? I just assumed anyone who could get through to the lump of ice in your chest would have to be a complete ball breaker. She looks really nice.”

“Screw you.”

The woman’s smile turned cheeky. “You do. But yeah, I forgot. You’re the ball breaker.”

“Sumi.”

“On it, boss.”

Toks turned her attention back to the work.

An hour later, they had the Steinways down to two – a bright instrument that was Toks’ preferred sound, and a mellow piano that Yajing liked for its more present touch.

The impasse meant talking to the piano technician.

Told you so,mouthed Sumi.

“Just fetch her, please,” Toks said with a thin-lipped smile.

It irritated her far more than it should have that Sumi and Polly were both laughing when they returned.

Like a coward, Toks stepped back and let the representative from the House introduce Polly to Yajing and explain the issue.

Polly ran her hand over the more mellow of the two pianos with the gentle touch of a lover. Toks watched it and clenched her teeth.

“This one is a favourite for many performers,” Polly told Yajing, and paused, patient and considerate, for her translator. She was confident and engaging, and her positive attitude made Toks’ simmering annoyance set like concrete. “It has a lovely touch, and I’m sure I can brighten its tone to please both you and the maestro. Should I get to work re-voicing, and we can reassess after tomorrow morning’s rehearsal? Maestro?” There was something hopeful in the questioning smile she turned on Toks.

Toks was still too bruised to deal with whatever the fuck that was.

She flicked her fingers with a dismissive nod and watched the hope freeze on Polly’s face. Three mechs swooped in to start moving the pianos back to the basement. Toks knew it was a dick move, but when Yajing sat down at one of the Steinways again and began to play, Toks sat next to her and they improvised a few different rounds of the Paganini variations. Playing with someone like Yajing was good for Toks – there weren’t too many people who could challenge her skill set – and they were dancing along the edge of brilliance in no time. She glanced up once, sly and smug, only to see Polly watching them both with an awful expression on her face – raw, haunted and grieving something precious. Toks had to drop her head and pretend to be focussed on her line.

Bitch, Sumi mouthed at her, from behind Polly’s back.

Sumi followed Polly and the mellow Steinway down to the basement, both of them chatting away like old friends the moment their backs were turned, and Toks went back to her office.

The hum in E flat drove her out of her mind, so she took her study back to her empty apartment.

Alone.

She found out what Polly and Sumi had been up to together the next day.

She was three hours into a four hour call with Rebecca Herzog and the orchestra, and deep in the final movement of the Tchaikovsky when a noise from the empty auditorium behind her scratched at her mind.

She silenced the orchestra.

Sumi and a front of house member were showing her mother and an excited gaggle of her geriatric nursing home friends into M row. That Magpie woman was with them, pushing Draga’s wheelchair and gaping at the splendour of the concert hall. Toks was just about ready to throw her baton down and pitch the kind of fit only maestros of her stature could get away with when Sumi cleverly preempted her.

“Sorry to interrupt your work, everyone,” she called, “but this is Mrs Tokarycz – the maestro’s mother. And some of her friends.”

Toks was supremely irritated when a good number of the orchestra cheerfully waved.

“Hey Castelli!” Magpie’s dry tones rumbled through the auditorium. “So you do work. Fancy.”

Richard’s mates in the strings section jeered. He stood up and took a small bow.

Toks glared at her assistant. Sumi smiled pertly back.

Draga folded her hands in her lap and looked at Toks expectantly.

For fuck’s sake.

Toks turned her back to them all and focussed on the music.

To pour salt on the wound, Sumi invited the gang from Nerradja into the green room after the rehearsal.

The green room was a large lounge area set between the two main concert halls reserved for the artists and crew of all seven of the Sydney Opera House’s performance spaces. A cafe served meals no matter the time, a battered, well-used piano sat in a corner, and most of the wide, comfortable sofas faced the view across the water and over to Kirribilli.

A bank of screens showed the stages of each performance space.

Musicians, opera singers, actors and techs lounged and waited the few hours before the afternoon’s rehearsals and performances.

When Toks emerged from her office, Sumi and Richard were arranging coffees for the oldies, and Magpie looked like she’d settled in. She was chatting up a fit looking woman from the opera chorus. An annoying number of Toks’ own musicians seemed keen to properly meet her mum.

“I played violin,” Draga told a young woman Toks vaguely recognised as a second violin player. Third row. “Back in Korovinja, before the Troubles. I wanted to play in the orchestra but, of course, the Severin Philharmonic didn’t accept women players in those days.”

“Seriously?”

Toks barely hid an eye roll. The woman was almost half her age. She didn’t know how easy she had it.

“They’d never have tolerated a woman on the podium back then,” Draga insisted.

The woman tittered nervously and cast a star-struck look at Toks.

“I’m sure you don’t even remember it, Ksenia,” Draga went on. “The elegance, the sophistication. The concert hall at Severin is such a beautiful building.” There was a distinct note in her tone that suggested the concrete and tiles of the Sydney Opera House couldn’t compete. “Every famous soloist from around the world played at Severin. We engaged only the very best conductors.” Toks bit her tongue. “And the parties! Soirees with everyone in the finest fashions. Flirting with your father.”

Toks made a disagreeable noise. She stood, pointedly not sitting down to join them. She could see a grand piano being wheeled to the stage in the concert hall – the instrument Polly had been working on. She and Yajing Tan would inspect it in a moment.

“Dad wasn’t into music,” she said, thoughtlessly.

Draga switched to Korovinjan as if her audience of admirers weren’t even there. “And you’d know? You barely spoke to him, you ungrateful child.”

“He was a miserable old grump who loved his cows more than he loved us.”

“He was in shock, Ksenia. Just like we all were.”

The look on the second violin player’s face made it immediately clear she also spoke Korovinjan. Toks took a proper look at her. Blond hair of the typical Korovinjan phenotype. Green eyes. Cheekbones. Round Australian accent. She could easily be the first generation child of refugees who’d escaped the country in the same wave that Toks had. The poor thing didn’t know where to look.

Draga hadn’t noticed and Toks couldn’t be bothered sparing her the embarrassment. She was the Creative Director of every note of music heard in this entire building, she had concertos with the world’s finest soloists to rehearse. She didn’t need a dressing down from her own mother in front of her colleagues.

“The whole world changed once he found out what his father was, what his brother was, and what they were doing to our beautiful country. You think it’s an easy thing to run from everything you know?”

The violin player’s eyes were like saucers flicking between Draga and Toks and making too many connections. Her mother was being indiscreet. Toks looked at the monitors again. Polly was on the stage now, tuning the piano.

“Oh my god,” the violin player breathed. “Tokarycz.”

Toks needed to get out of there. The whole thing felt deeply unfair.

“I ran,” she pointed out. She’d been a refugee too.

Draga gave a mirthless laugh. “You always do, Ksenia.” She tipped her head at the bank of screens. Her expression softened as she watched Polly, but was hard as steel when she looked back at Toks. “Over and over again. You’re still acting like a spoiled child. Spoiled and blind. And you never care who you hurt.”

Her mother was far, far more astute than Toks had given her credit for.

Toks aimed a smile at the second violin player. “Excuse me, please,” she said in English. “I have work to do.”

Toks stood in the wings and watched her.

The piano was centre stage, lid open and sideways to the audience – exactly as it would be positioned in performance. Polly had her back to her bent over the keys, half in and half out of the piano as she tapped on her tuning hammer and struck the keys. The sounds clashed in Toks’ head.

Polly tuned in the traditional way – of course she did – and it was clear she was just finishing up, making her way around octaves that were already very nicely in tune, tweaking and brightening the tuning to match the room. Her head tilted as she listened, her hair caressed the nape of her neck as she leaned into her task. Her sleeves were rolled up and her fingers were lithe and graceful as they sought out the keys she wanted without looking. The lush roundness of her backside, taut in a pair of deep indigo jeans, twitched rhythmically with each tap against her wrench. Toks wondered what was wrong with her that she couldn’t take her eyes from her.

The circle of fifths up and fourths down. Reference checking the thirds and sixths between. Perfect octaves knocked slightly imperfect, the merest dissonances between the harmonics in the upper frequencies providing exactly the brightness Toks was seeking. A machine would have tuned things so precisely the sound would be dull. Polly’s talent lay in challenging that perfection – just enough to take the tones fractionally out of phase, just enough to make her artistry dazzle.

Her ear was extraordinary. There were years of skill and dedication at work here. Polly was a master. The piano sounded perfectly imperfect.

Toks realised who had tuned her office piano. And re-voiced it. That must have been an overnight job. You didn’t re-weight, re-voice and tune a piano in under four hours. Polly must have spent the same amount of time – hopefully more – on this instrument.

At Toks’ order.

A cascade of worries tumbled out of nowhere.

Had Polly been home? Had she worked all night? Jerinja was a two hour drive away. Had she risked the roads on so little sleep just to tune Toks’ piano? Or did she stay in town? And where? Had Polly been camped out in some grubby hotel uptown while Toks had been lamenting her empty luxury apartment barely metres from the Opera House? They could have had dinner. They could have— Had Polly been lonely—?

She stopped herself.

She didn’t care. She shouldn’t care. If she cared, she was only setting herself up again for another dose of pain. Polly Paterson wasn’t Toks’ concern and hadn’t been for sixteen years.

Why the hell should she give a shit now?

There was something odd, though, in Polly’s method, Toks realised. She frowned and leaned against the door where she hid in the darkness of the prompt corner. Polly’s patterns of intervals had taken her all around the keyboard – all eighty-eight notes. Except for one.

The F sharp below middle C.

She knew now that Polly was damaged, but how, exactly, she was too proud to ask. She couldn’t do this again. She’d waited too long. She’d waited in that bone-numbing cold. No message. No call. Just a ghosting before the word had even been invented. Just that awful, crushing, squeezing feeling that grew, day after day after day, as she frantically exhausted every avenue of help she could think of, until even the baffled and bewildered bureaucrats at the embassy had blurted it out.

Maybe your girlfriend just doesn’t want to see you. You ever think of that?

What the hell was wrong with Toks that sixteen years later she still couldn’t get the memory of Polly Paterson out of her body?

“Fascinating to watch, isn’t it, Maestro?”

The coordinator from the House appeared beside her, with Yajing Tan and her husband. On stage, Polly pulled the final note into line – the F sharp – then gathered up her tools. She stood to one side and accepted Yajing’s gratitude as she declared the piano utterly perfect.

“And you, Maestro?” the coordinator asked. “Are you happy? Are we all good?”

A stupid expression, Toks thought. No staff member from any other concert hall in the world would speak so casually to her. She was not happy. And nothing, nothing about this entire situation was good.

She couldn’t stop herself.

She reached around Yajing’s shoulder and hit the F sharp.

Polly’s expression froze, but the piano was precisely what Toks had asked for.

“It’s acceptable,” Toks said.

Sumi strolled onto the stage.

“Draga and Magpie and everyone are going to dinner at the Opera Bar before the performance. Are you coming, Toks?”

“‘Draga’, now, is it?” she muttered.

“Polly’s going to be there, aren’t you?” Sumi smiled.

Polly nodded.

Toks pictured them both sharing a meal before a performance – maybe in Hamburg, perhaps in Berlin, definitely in Severin. They’d eat early, both of them needing to focus and concentrate before the evening’s concert. Then they’d hole up in Toks’ dressing room, Toks reading her score, Polly humming the cello line and slipping into a slim black dress. Toks would help her with the zip. They’d kiss for luck at the five minute call and Polly would brush the lapels of Toks’ jacket with the backs of her fingers and smile that cheeky, addictive smile.

Toks would be brilliant on the podium, but she’d watch for Polly in front row of the cellos – that tweak of one eyebrow that would always let Toks know if she overdid things. They’d slip back into jeans and comfy clothes, and sneak out the loading dock to avoid the fans at the stage door. They’d go for cocktails on the stroll home, then giggle their way up to bed and Toks would fall asleep with her face on Polly’s breasts and Polly would tickle her scalp with neat, short nails – and the next day they’d do it all again.

It had been a foolish dream.

“I have a performance to prepare for,” Toks gritted.

The hopelessness on Polly’s face almost matched the feeling in Toks’ heart.

After one more week of performances, she and Sumi were back on her cousin’s private plane getting the hell out of Sydney and back to Europe.

Fullepub

Fullepub