Chapter Forteen

“Alright, I’ll bite. What are you so cheerful about? People are starting to worry.”

They were in Toks’ apartment in Severin, having just arrived from Hamburg. The insanity of the Ring Cycle was behind her and she was… happy… to be in Korovinja again, a week of celebration and Korovinjan music ahead of her.

And then back to Sydney.

She smiled at the thought.

“Look! There it is again. You’re doing something weird with your face.”

There was a laugh from her assembled friends. It made Toks feel… relaxed.

They were very new feelings.

“Careful, Sumi,” said Artis. “We want it to last.”

“Pfft.” Sumi was sceptical. “Whatever it is, she’s freaking me out. And she won’t put her phone down. Time was she never looked at it and left all the mundane stuff that lesser beings worry about on their phones to me.” Sumi slung plates around the coffee table and bustled with takeout containers. “Something is going on.”

Toks glanced up from her phone, stuck her middle finger up at the lot of them, and went back to texting Polly.

She ignored their chuckles.

Polly was making some ridiculously cheeky remarks about Toks’ supposed inability to properly understand the subtleties of track layering as opposed to orchestral texturing and that Toks was overscoring things like she thought she was Wagner. Toks challenged that any piece that contained a drop was even capable of subtlety and it had been on. They’d been texting since she got on the plane back in Hamburg and hadn’t stopped.

It was eight in the morning in Sydney and Toks could picture Polly just in from a surf, her hair wet and tangled with salt, a cup of tea steaming on the balcony at Jerinja. She’d be smiling, texting Toks back at top speed and forgetting about the breakfast beside her.

In Severin, it was nine in the evening and Toks was having a quick bite to eat before her cousin and his mates dragged her out clubbing. Except that she’d almost certainly be dancing to something by Tightly Strung at some point, she almost didn’t want to go.

There was the most incredible feeling of lightness in her head making her dizzy. She could hear angels on the wind.

“Could be love,” her cousin said.

The laughter was so cruel Toks finally put her phone down. Arseholes.

Nikoloz Konstantyn Tokarycz, Korovinja’s most beloved billionaire, was slouched in her sofa next to her. He was two years older than Toks and almost her spitting image – the Tokarycz genes were strong – golden hair, green eyes, cheekbones to cut yourself on. Their fathers had been brothers, though Nikoloz’s father had never escaped the regime and run to Australia as Toks’ family had. She remembered playing in the snow with him and her brother when they were kids, chasing him through the endless rooms of their extravagant apartments, irritated when the boys won every game simply because they were bigger and stronger.

That playful, competitive vibe had continued into their grownup life, though the imbalance now came from the vast influence Nikoloz Tokarycz had over all European business and politics, and the absolutely filthy level of wealth he enjoyed. Toks wasn’t going to complain, though. She bummed flights on his private jet almost weekly, and the tens of millions he poured into the various music programmes she’d established across Europe more than made up for any residual childhood jealousy.

Also, Toks’ parents hadn’t been executed for crimes against the state like Niki’s had, but they didn’t go there. That was a rubbish thing to lord over anyone. It wasn’t like the Troubles had been her cousin’s fault.

Most of the time, he was dearer to her than her own brother. Right now, he could drop that teasing shit before she thumped him.

“And what if it is?” she asked, mildly. “Love.” She hadn’t used that word in a long time.

The group hooted and jeered.

“Not possible,” declared Sumi. She passed Toks a plate and smirked.

“Oi! Screw the lot of you,” cried Toks, but she couldn’t stop her smile.

“You nearly have.” Nikoloz’ boyfriend Artis was pouring the champagne. He looked around, pointing to the women in their circle – a soprano, a socialite from the orchestra’s Board, and Sumi.

“Shut up, Artis,” she said under a new cascade of jeers. She knew she had a reputation. She just didn’t appreciate it coming to roost at this particular moment. She shot apologetic glances at the women – not Sumi – and was grateful for their understanding smiles. The maestro was always up for a good time and her conquests knew never to expect anything more.

For the first time in a long time, Toks found herself a tiny bit uncomfortable about that fact.

Her phone buzzed and Toks snatched it back up again. The laughter was rich.

She’d overreacted at the Nerradja Country Fair. Now that she’d slowed down enough to think about it. It was the stab of hurt – the pure, unadulterated pain that shot from nowhere and hit her as hard as it had all those years ago – that had taken her by surprise. Logically, it made sense. Polly had a daughter. Generally speaking, the easiest way to obtain such a thing was by sleeping with a man. And Polly, her body, her love and her life had been such a part of Toks that the merest thought of someone else touching her had been a violation she hadn’t known how to deal with. To discover that Polly had… done that… at almost the exact same time she’d promised to meet Toks in Berlin had reawakened years-old agonies and poured on acid.

The soothing tug of Jerinja and the impossible hope of a fairy floss flavoured kiss at the fair had simply made it all the more devastating.

But she shouldn’t have run away. Toks shouldn’t have spent the next three weeks ignoring her. She shouldn’t have so eagerly retreated to her cousin’s private plane and the other side of the world just because Ksenia Tokarycz was a gutless coward who hadn’t learned or changed in sixteen years.

Because Polly’s silent tears shining on her cheeks as Toks had led the orchestra through all that luscious Rachmaninoff had nearly had Toks undone. She’d been there every night. Always way up in the choir seats, half in the dark. And Toks had known she was there. Known. Felt it in the beat of both their hearts like a metronome.

It wasn’t until she was on the plane, Sumi laughing with the attendant and the pilot and leaving Toks to her mood, that she realised how stupid she’d been.

Polly replied to her texts in the middle of the insanity of back-to-back Ring Cycles and Hamburg had never looked so beautiful. Sumi made her usual jokes about the harem of nine gorgeous women Toks engaged to play the Valkyries and the Rheinmaidens, and Toks didn’t even hear her. Uptight tenors, stressed horn players, eighteen tuned anvils and fifteen solid hours of music in performance, and Toks did the whole thing with only half a mind.

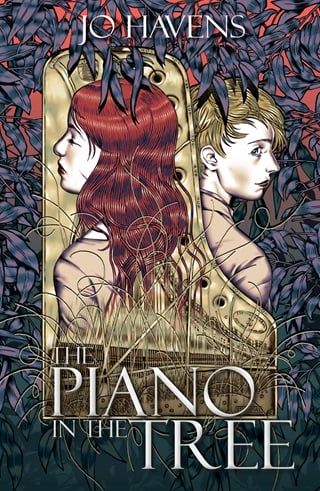

A photo of Polly and Tilda under the quince tree in the orchard at 613, their backs leaning against the ruined piano there became a treasured picture in her phone. An image that Tilda sent her of Polly tuning that damned chook-shed Blüthner in the music room at Jerinja was the first and last thing Toks looked at each day. She chatted business with Polly at first – the mechanics of scoring electronica for orchestra – and then they chatted trivialities. It took just one short day until they were poking fun at each other. A week and they were definitely flirting.

They hadn’t actually talked but Toks had the blossomest feeling that she might finally, maybe, possibly be on the way to doing something right.

So she grabbed at her phone the moment it buzzed and ignored her friends. She swiped it open with her heart in her mouth. She’d been right about breakfast on the balcony. The first pic was of the view down Thirteen Mile Beach. The second was better. A selfie, Polly in a thin floaty shirt over a green bikini top with—

Nikoloz plucked the phone neatly from her fingers. He shot one irritatingly elegant eyebrow at the screen. Toks let him look. For some reason, Niki’s approval felt important.

“It must be love,” he mused. He held up the phone for everyone to see with a wicked grin. “The world-renowned Maestro Tokarycz has never stooped to shagging surfer-babes before. And one her own age at that!”

Toks launched a volley of punches at his shoulder, roaring her outrage and secretly loving the laughter that rang around them. This was a play straight from her lost childhood and it was a crazy delight to have that simple pleasure again, even as she railed at his teasing. She had to work to get a decent thump in – her big cousin had had ten years in the military in Korovinja before the regime fell – but she put up a fine fight, the group cheering her on.

It took Artis and Sumi to separate them, sighing like put-upon parents. Artis handed around the bubbles. Sumi stepped back to let everyone get to the takeout meal she’d spread on the table, and while everyone was distracted she returned Toks her phone.

“Proud of you, boss,” she murmured. “It’s a long time since you’ve let yourself be this human.”

Toks should have had a snarky comeback for that, but her mind was full of Polly Paterson and there was the tantalising hum of music on the air.

Toks’ apartment in Severin was one of the elegant treasures from the 1700s that faced the Kjarta Harmonja, the grand old square that graced the centre of the city. She had the whole third floor – thirteen foot ceilings, parquet floors and vast white framed windows that let in the early spring morning. They framed a postcard view across one of Europe’s most beautiful cities – the concert hall, the summer palace of the old kings, and a cathedral to rival the Notre-Dame de Paris. The river glistened in the background, wending its gentle way between stone and tree-lined banks, the entire scene festooned with the green banners celebrating the anniversary of the revolution.

But Toks saw none of it.

“Maestro, we need to move. Sending you updates to today’s schedule now. The car is downstairs.”

Toks was slightly hungover but she was attempting to play it out at the piano. She had that selfie of Polly on her phone propped up on the music stand and was letting the music tumble straight from her eyes to her fingers. Modal inflections and rippling chromaticism over a shifting tonal bed inspired by those pianos Polly had placed in the river and on the escarpment. A palette of hope and potential, and a wistful dance of melancholy and joy – and she didn’t even hear Sumi bundling today’s scores into her bag.

A takeout coffee hung in the air in front of her face.

“That’s gorgeous, Toks. I can’t decide whether it’s Poulenc or Debussy. Or Ravel? No. Too liquid. Satie? Who—? Oh.”

Sumi saw the pic of Polly on her phone. She was kinder about it than Toks deserved. She nudged her with her arm and Toks stopped playing. She blinked and took the coffee.

“Come on, Romeo,” Sumi said, gently. “I’m glad you’re happy, but we’ve got a very busy day ahead. Breakfast TV interview, Classic FM interview and a meeting with Nikoloz’ people before we even get to rehearsals. You’re gonna have to snap out of it.”

It was four in the afternoon in Sydney. Toks wondered what Polly was doing, then shook it off with a deep breath.

She snapped her phone closed, took the coffee Sumi offered, and strode downstairs to the car.

The Severin Philharmonic knew the famous pieces from the great Korovinjan composers by heart and could play them with their eyes closed. The programme Toks had selected to celebrate the anniversary of the revolution was a crowd-pleaser that generally wouldn’t be worth her time – except that she was the world’s most eminent conductor and Severin had long since claimed her as their own. Besides, the orchestra was a pet project of hers and most of the musicians in it were friends.

She ran the rehearsal laughing from the podium, whizzing them through the music and only giving notes in places where she intended to draw out particular responses from the audience. Spirits were high.

Sumi bustled her immediately on to her Women on the Podium programme, catching up with some of the ten young women selected from all over Europe to participate in her prestigious school. There was a lecture at the Severin Academy after that, and then the bit Sumi looked forward to every year.

“We’re walking you straight into the top of the second half,” Sumi told her, holding out her jacket for her. Her smile was wicked and her eyes glittered. “Hot fucking damn, Maestro. It is sinful how good you look in this.”

Toks rolled her eyes. “It’s a kids’ show. It’s not supposed to be sexy.”

She was in a ridiculously cheerful mood. She shrugged the jacket on and fiddled with the lace at her wrists. The maeve frock coat with a brocade waistcoat was designed by the costumiers at the Korovinjan Opera Company to match the maeve silk pantaloons and white stockings she was already wearing. She was dressed as Korovinja’s most famous composer from the 1750s right down to the heels with buckles and the powdered wig. Mozart would have been jealous.

Sumi held up her phone to take a picture, a viciously hungry smile on her face.

“You are a weird and twisted woman, Sumi,” Toks told her.

“It’s for social media!”

“Of course it is.” But Toks lifted her chin and threw her shoulders back anyway. The frock coat hugged her waist and flared out over her hips. The high collar set off her cheek bones. She cut a very fine classical figure even if she said so herself.

“I might send it to Polly though.”

“What?!” Toks lunged for her phone, but Sumi danced out of her way.

“There’s your score, Maestro, marked up by your assistant conductor. The youth orchestra is pumped, there’s a full house and the first half has gone brilliantly. You’re on in five.”

The three Korovinjan youth orchestras were another of Toks’ programmes funded on her cousin’s euro. Every year for the anniversary, she combined the three of them into one mega band and put them all centre stage in the main concert hall. Parents and grandparents booked the place out and the Dom Harmonja overflowed with music and family and the laughter of children.

Toks’ costume became more elaborate every year too.

Secretly, she loved this shit.

“Who’s my co-conductor?” she asked.

A nation-wide competition awarded one lucky music student the chance to conduct at her side.

“A seven-year-old named Nina. She has leukaemia. You’ll meet her in a moment. She’s actually quite a talent.” Sumi fussed with the lace cravat at Toks’ throat, then thrust her baton into her hand. “That’s our five minute call. Let’s go.”

She was piano rehearsing the violin soloist the following day when her phone buzzed in her pocket.

“My apologies,” she murmured and flicked her fingers at her associate conductor. “I have to take this.”

Sumi’s eyebrows shot to the ceiling and Toks escaped the room.

Polly was nearly crying with laughter. “You look like crusty old Salieri.”

“Salieri? Salieri? Pearlie, how you wound me! Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart would be jelly on his knees before me. That was the height of 18th century fashion, I will have you know.”

There was a snort-giggle all the way from Jerinja. “Matches your eyes,” Polly laughed. “But, why, though? Not that I’m judging, babe, just, why?”

Toks’ insides liquidised on the word babe.

“Kids’ concert series,” she said, playing it down.

“A kids’ concert series?” Polly said, flatly. “You? You conducted dressed like that?”

“Just one piece,” Toks protested. “And I was only assistant conductor. The real maestro was a seven-year-old named Nina.”

Polly gave a puzzled huff. “What was the piece?”

“Theme from How to Train Your Dragon. Nina picked it.”

“Who are you?” Polly asked.

Toks laughed. “Pearl, I have to go. I’m rehearsing Anne-Sophie Mutter.”

“Of course you are.”

She couldn’t resist. “Bruch’s first.” Only the most popular violin concerto in the repertoire with one of the world’s incomparable soloists.

“She’s hot,” Polly deadpanned.

“Oi! She’s sixty.”

“Milf. She doesn’t need to dress up.”

“I’ll talk to you later, Pearlie Paterson.”

Polly’s laughter rang in her ear.

The rest of that day was a blur of meetings with the creative and management teams for the anniversary celebrations. An outdoor concert in the Kjarta Harmonja perfectly timed to sync with a firework display dazzling the skies over the cathedral and the concert hall, plus literal cannons in her percussion section.

She was shattered by the time they were all over.

Nikoloz and Sumi suggested a nightcap somewhere, but they both smiled knowingly when she said she just wanted to get to bed.

“What’s her name?” Niki asked. “This surfer girl of yours.”

“None of your business,” she told him, tartly. “And you can both stop grinning like that. I’m actually tired. I’m going to sleep.”

Niki pretended to consult with Sumi. “The Ksenia I know would come out with us,” he mused.

“The maestro is getting on,” Sumi pointed out. “She has a Chopin recital tomorrow morning for the blue rinse brigade in the city recital hall, and she’s conducting a Czerny concertino from the piano in the evening.” She gave Toks a piercing look. “Plus she’s mentoring one of her students through the orchestra rehearsal tomorrow. Please don’t forget that, Toks.”

“Does she even have time for love?”

Toks wasn’t so sure.

But she wanted to hear Polly’s laugh again. She left the two of them bickering and took a taxi back to her apartment.

Her timing was good. Polly was at the beach surfing with Daz.

Toks got a much better look at that bikini.

The rest of her week passed at the same frenetic pace, all building to the concerts and outdoor spectaculars that celebrated the fall of the Vass regime sixteen years ago. Her musicians, her soloists, the staff at the concert hall, every person in the entire country was in a good mood, and adding that to the flirting thing she had going with Polly Paterson meant Toks had never been happier either.

It wasn’t until just before the prestigious Saturday night concert in the Dom Harmonja, that it occurred to her to send Polly a selfie from her favourite place.

She persuaded the stage manager to let her take a snap on the podium before they opened the house. She wasn’t in her tux and white tie yet, but that was okay. She caught the gorgeous vaulted ceiling of the space, the plush red velvet of the seating as it curved away behind her. The gold filigree on the private boxes that lined the walls. The Dom Harmonja was one of Europe’s most beautiful concert halls, having survived way more than its fair share of wars, and Toks had loved it since she was a kid.

Now she stood on the podium in the very heart of it.

She pressed send on the picture with more hope in her soul than had dwelt there for a long time.

And then she was swept up in the concert. Then the soiree afterwards. A quick change and she was back on stage at the outdoor event in the vast square at the Dom’s door. A different orchestra, a completely different sound – those damned cannons – and the fireworks.

After that, Sumi’s schedule finally emptied out and the party really kicked off. Severin was a beautiful, glittering jewel of a city in the middle of the country that had once been her home, and she snapped a hundred more pics to send to Polly.

Niki and Artis insisted she join them for a rooftop party on the edge of the square, and some time around three a.m. she found herself dancing to a shamelessly sampled Schumann riff and realised it was Tightly Strung. She could hear Jerinja in its infectiously joyous beat. Eucalyptus hit her brain in a tingling rush and the blue of the world at the edge of the escarpment called to her soul.

She checked her phone. There was no message from Polly, but she held it up and recorded a few seconds of the room jumping to the track, then the view of Severin from the balcony – the square and the Dom Harmonja all draped in the banners of the revolution.

It was beautiful.

Sumi dragged her out a bit later with the motherly reminder she’d be on a plane to Sydney in a few hours and that she had a rehearsal the moment she landed, and had she even gone over the Sch?nberg yet?

There was still no message from Polly.

She crashed into a first class cabin on the commercial flight, tugged noise-cancelling headphones over her ears and watched her phone. She endured the hustle and inconvenience of Dubai’s premium private lounge during the stopover and cursed the twenty hours of flying time between Korovinja and Australia. There was plenty of signal in the world’s richest city, but no messages from Polly. She drank substandard whisky on the Dubai-Sydney leg and glared at the Sch?nberg until she had it in her head.

The plane deposited her into the harsh Sydney sun, a day far hotter and drier than any April morning had a right to be, and still her phone was silent.

A car took her down to the Quay where a thousand aimless tourists wandered the foreshore, where the Sydney Opera House rose like a lotus flower from the Harbour and she knew she was in the same timezone as Pearlie Paterson once again.

Polly hadn’t contacted her since that selfie in the Dom Harmonja in Severin, and the blossoming potential of that moment seemed a whole world away.

The air conditioning vent in her office hummed in E flat.

“No! Horns, you are still late on that pick up to 62. Watch please, people. I’m not waving my arms around for the fun of it— agh!”

She tossed her baton onto her music stand, slumped on her stool and regarded the entire brass section from under her brows. That was a tanty of the kind only maestros of her calibre could throw but she was ashamed of herself for indulging.

“My apologies,” she muttered, flicking through her score again. “It’s just so bloody hot. I’m not used to it.” She let them have a laugh at her expense. “Europe’s made me soft. Let’s take it again from the beginning of the rondo.”

Richard Castelli watched her from the viola section with concern.

“Is Polly well?” she asked him, catching his arm in a corridor after the rehearsal. It was Thursday. Polly had left her on read for five days and Toks was a coward all over again.

“Why don’t you come down to Jerinja after the concert on Saturday night?” he said. “Daz always puts on a barbecue on Sunday afternoon. Everyone’s welcome. White wine in the sun, and all that.”

The thought almost made her cry. She sniffed and raised her chin.

Richard noticed.

“I’m not going to take no for an answer, Maestro,” he said, gently. “I’ll talk to your assistant and book it in. We’ll share the driving. I’ll see you at the stage door at ten-thirty sharp, Saturday night.”

It wasn’t a kindness Toks deserved, but she wasn’t going to turn it down.

Fullepub

Fullepub