What We Don’t Know The Story Behind the Story

What We Don’t Know:

The Story Behind the Story

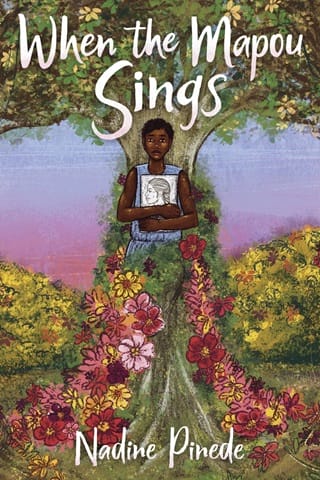

This novel is set in Haiti from 1934 to 1937, right at the end of the nineteen-year US occupation. It’s inspired by real events—and by a mystery surrounding them.

First, the real: Zora Neale Hurston went to Haiti on an anthropology fellowship in 1936. While she was there, she wrote her masterpiece, Their Eyes Were Watching God . And in her nonfiction book on Haiti and Jamaica, Tell My Horse , Hurston praised a Haitian woman named Lucille, who worked as her domestic.

Now, the mystery: Nothing else is known about the real Lucille. And Hurston’s fieldwork notebooks have vanished.

Enter the magic of the historical verse novel. It has the power of intimacy and emotional resonance to paint history in primary colors.

In centering Lucille’s story, I was largely inspired by three sources:

the stories my mother told me about her grandmother, a bold market woman who lived through the occupation and narrowly escaped serious trouble

the mystery of what happened to Hurston in Haiti, including her fear that her research on zombies was leading to trouble

the work I witnessed by Chavannes Jean-Baptiste, the first Haitian winner of the Goldman Environmental Prize, whose anti-corruption activism did get him in trouble. Good trouble, as John Lewis would say.

Historical fiction is storytelling anchored in the past. Whenever possible, I tried to stay faithful to the historical timeline of major events, such as the withdrawal of US occupying forces in 1934, the 1936 summer Olympic Games in Berlin, and Hurston’s first period of fieldwork in Haiti, from fall 1936 to spring 1937. I am greatly indebted to historians Yveline Alexis and Brandon Byrd for their assistance in getting the history right. Any remaining errors or omissions are mine.

Based on my research, I invented the characters and the stories of Lucille and her family, the section chief and his mother, the Ovide family, Celestina, Fifina, Cousin Phebus, and Pince-Nez, among others.

I took the liberty of placing the Black choreographer, dancer, and anthropologist Katherine Dunham in Haiti in 1936 for the fictional Madame Ovide’s dinner party, although Dunham was not in Haiti at that time. In her letters, Hurston wrote often of Katherine Dunham in terms of a rivalry, pushed to compete against each other by their respective mentors, the anthropologists Franz Boas and Melville Herskovits. Unlike Hurston, Dunham made Haiti her home for decades, and she was eventually honored by the Haitian president for her contributions to Haitian culture. I gave her a cameo as a foil and to introduce some of the other real figures who represented Haiti’s “talented tenth,” to use the intellectual activist W. E. B. Du Bois’s term. Du Bois himself was of Haitian descent.

The Haitian notables gathered at Madame Ovide’s are among the many who worked for a democratic civil society and promoted the serious study of Haitian culture. These included the anthropologist Jean Price-Mars, sculptor Hilda Williams, editor Jeanne Perez, along with others in the women’s rights movement, and the prominent Sylvain family, particularly Suzanne Comhaire-Sylvain, the first female Haitian anthropologist.

I cast author and activist Jacques Roumain as an older role model for Oreste Ovide. His biography, A Knot in the Thread: The Life and Work of Jacques Roumain , by Carolyn Fowler, also helped me imagine how the Ovides might have lived.

When the Mapou Sings is about a lesser-known period in history that is relevant to our uncertain times. History is a song that enriches us all as more voices are included. Today there are young people like Lucille, Oreste, Fifina, and Phebus who are fighting every day to create a thriving Haiti and who are beacons of hope.

Bibliography

Notes on Selected Sources

For me, writing historical fiction took patient detective work and obsessive curiosity. As a historian by training, I’m particularly drawn to primary sources. Here are some of the key resources that helped me imagine a world I could never visit. Full citations follow as needed. For more information, please visit www.nadinepinede.com .

The statement from the US secretary of state on page 7 is from Address of the President at Cape Ha?tien, Haiti, July 5, 1934, and “Final Ceremonies in Haiti,” Marine Corps Gazette , November 19, 1934, a copy of which was shared with me courtesy of Professor Yveline Alexis, Oberlin University, and the original of which is held at the United States Marine Corps History Division Archives in Quantico, Virginia.

A helpful “Tourist Map of Haiti,” drawn by M. P. Davis, was used by the American “song hunter” Alan Lomax during his visit to Haiti in 1936–1937. It’s included in the ten-CD boxed set Alan Lomax in Haiti, 1936–37: Recordings for the Library of Congress . The set also includes Lomax’s Haitian Diary , in which he recorded his meetings with Zora Neale Hurston. Some of Lomax’s film footage from Haiti is available on YouTube.

The songs I included are folk songs I heard during my time at the thirtieth anniversary of the Papay Peasants Movement. Modern acoustic guitar versions of “Latibonit” and “Mesi Bondye” by Haitian American Leyla McCalla are available on YouTube. The lyrics of “Choucoune,” known in Haitian Creole as “Ti Zwazo” and in English as “Yellow Bird,” were written in 1883 by Haitian poet Oswald Durand.

A book of postcards of Haiti from 1895 through the 1930s, edited by Peter C. Jeannopolus, stimulated my imagination.

The photo Hurston took of Felicia Felix-Mentor, which she identified as the first photo of a zombie, appeared in a 1937 Life magazine article, “Black Haiti: Where Old Africa and the New World Meet.”

Regarding Hurston’s fascination with zombies, an article in Medium by Charles King, drawn from his book Gods of the Upper Air , on groundbreaking anthropologists, including Hurston, was an eye-opener for me. Science would suggest that Hurston was on the right track in her research, but only decades later; see Gino Del Guercio’s article cited in the bibliography.

Very few letters written by Hurston from Haiti still exist. I relied on Carla Kaplan’s Zora Neale Hurston: A Life in Letters and letters written by Hurston in Haiti to Henry Moe, at the Guggenheim Foundation.

Hurston’s niece Lucy Anne Hurston put together a sparkling collection called Speak, So You Can Speak Again: The Life of Zora Neale Hurston , which includes facsimiles of Hurston’s handwritten notes, as well as early poems, painted postcards, and a CD of songs and interviews.

My mother’s great-uncle Arsène V. Pierre-Noel wrote the first book on the healing properties of Haitian botanicals, called Les plantes et les legumes d’Ha?ti qui guerissent .

Some first-person accounts from Americans were useful, such as US Marine Corps Captain John Huston Craige’s “Haitian Vignettes” and US Marine Corps Major G. H. Osterhout Jr.’s “A Little-Known Marvel of the Western Hemisphere: Christophe’s Citadel, a Monument to the Tyranny and Genius of Haiti’s King of Slaves,” both of which appeared in National Geographic .

I expanded my knowledge of the rich tradition of Haitian proverbs with Edner A. Jeanty’s Paròl granmoun: Haitian Popular Wisdom: 999 Haitian Proverbs in Creole and English .

Sources

Address of the President at Cape Ha?tien, Haiti, July 5, 1934. Collection FDR-PPF, President’s Personal File, 1933–1945, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Papers as President, Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum, Hyde Park, New York.

Bell, Beverly. Walking on Fire: Haitian Women’s Stories of Survival and Resistance . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2001.

“Black Haiti: Where Old Africa and the New World Meet.” Life , December 13, 1937, 26–31.

Bontemps, Arna, and Langston Hughes. Popo and Fifina: Children of Haiti. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993. First published 1932 by Macmillan (New York).

Boyd, Valerie. Wrapped in Rainbows: The Life of Zora Neale Hurston. New York: Scribner, 2003.

Craige, John Huston. “Haitian Vignettes.” National Geographic , October 1934, 435–485.

Davis, M. P. “Tourist Map of Haiti,” drawn for Haiti, a Brief Historical Review and Guide Book (1933). Alan Lomax Collection, Manuscripts, Haiti, 1936–1937, Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/resource/afc2004004.ms120274/ .

Del Guercio, Gino. “The Secrets of Haiti’s Living Dead,” Harvard Magazine , January– February 1986. https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2017/10/are-zombies-real .

Dubois, Laurent. “Who Will Speak for Haiti’s Trees?” New York Times , October 17, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/18/opinion/who-will-speak-for-haitis-trees.html .

“Final Ceremonies in Haiti.” Marine Corps Gazette , November 19, 1934.

Fowler, Carolyn. A Knot in the Thread: The Life and Work of Jacques Roumain . Washington, DC: Howard University Press, 1980.

Hurston, Lucy Anne. Speak, So You Can Speak Again: The Life of Zora Neale Hurston . New York: Doubleday, 2004.

Hurston, Zora Neale. Dust Tracks on a Road: A Memoir. New York: Harper Perennial, 2006. First published 1942 by Lippincott (Philadelphia).

——. Fo lklore, Memoirs, and Other Writings. Edited by Cheryl Wall. New York: Library of America, 1995.

——. I Love Myself When I Am Laughing . . . And Then Again When I Am Looking Mean and Impressive . Edited by Alice Walker. New York: Feminist Press at CUNY, 1979.

——. Letters to Henry Moe. October 14, 1936; January 6, 1937; April 5, 1937; May 23, 1937; September 24, 1938; March 20, 1937. John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, New York.

——. Tell My Horse: Voodoo and Life in Haiti and Jamaica. New York: Harper Perennial, 2009. First published 1938 by Lippincott (Philadelphia).

——. Their Eyes Were Watching God. New York: Harper Perennial, 2006. First published 1937 by Lippincott (Philadelphia).

——. You Don’t Know Us Negroes and Other Essays . Edited by Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Genevieve West. New York: Amistad, 2022.

——. Zora Neale Hurston: A Life in Letters. Edited by Carla Kaplan. New York: Anchor, 2003.

Jeannopoulos, Peter C. Port-au-Prince en Images / Images of Port-au-Prince . New York: Next Step Technologies, 2000.

Jeanty, Edner A. Paròl granmoun: Haitian Popular Wisdom: 999 Haitian Proverbs in Creole and English . Port-au-Prince, Haiti: Presse évangélique, 1996.

Jennings, La Vinia Delois. Zora Neale Hurston, Haiti, and Their Eyes Were Watching God . Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2013.

King, Charles. Gods of the Upper Air: How a Circle of Renegade Anthropologists Reinvented Race, Sex, and Gender in the Twentieth Century. New York: Anchor, 2019.

——. “When Zora Studied Zombies in Haiti.” Medium , July 23, 2019. https://zora.medium.com/when-zora-met-zombie-dbcf0fb45d11 .

Lomax, Alan. Alan Lomax in Haiti, 1936–37: Recordings for the Library of Congress . San Francisco: Harte, 2009.

Lyons, Mary E. Sorrow’s Kitchen: The Life and Folklore of Zora Neale Hurston. New York: Athenaeum Books for Young Readers, 1993.

Martin, Alain, dir. The Forgotten Occupation: Jim Crow Goes to Haiti. 2 Hander and Pameti Films, 2023. http://theforgottenoccupation.com .

Moylan, Virginia Lynn. Zora Neale Hurston’s Final Decade . Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2011.

N’Zengou-Tayo, Marie-Jose. “Fanm Se Poto Mitan: Haitian Woman, the Pillar of Society.” Feminist Review , no. 59 (Summer 1998), 118–142.

Osterhout Jr., G. H. “A Little-Known Marvel of the Western Hemisphere: Christophe’s Citadel, a Monument to the Tyranny and Genius of Haiti’s King of Slaves.” National Geographic , December 1920, 469–482.

Paris, Robel. Haitian Recipes. Port-au-Prince: Henri Deschamps, 1955.

Pierre-No?l, Arsène V. Les plantes et les legumes d’Ha?ti qui guerissent: mille et une recettes pratiques . Port-au-Prince, Haiti: L’état, 1960.

Plant, Deborah G. Zora Neale Hurston: A Biography of the Spirit (Women Writers of Color). Westport, CT: Praeger, 2007.

Simon, Scott. “Haitian Soup Joumou Awarded Protected Cultural Heritage Status by UNESCO.” NPR, Weekend Edition , December 18, 2021. www.npr.org/2021/12/18/1065477169/haitian-soup-joumou-awarded-protected-cultural-heritage-status-by-unesco .

Tarter, Andrew. “Trees in Vodou: An Arbori-cultural Exploration.” Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture 9, no. 2 (April 2015), 87–112.

Timyan, Joel. Bwo Yo: Important Trees of Haiti . South-East Consortium for International Development, 1996. https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNACA072.pdf .

Twa, Lindsay J. Visualizing Haiti in U.S. Culture, 1910–1950 . Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2014.

Williams, Hilda. Hilda Williams: un hommage . Exhibition catalog. Port-au-Prince, Haiti: Musée d’Art Hai?tien, Ateliers R. Jér?me, and Centre d’Art, 1995.

“Zora Neale Hurston: Claiming a Space.” PBS, American Experience , 2023. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/films/zora-neale-hurston-claiming-space/ .

“Zora Neale Hurston: Jump at the Sun.” PBS, American Masters , 2009. https://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/masters/zora-neale-hurston/ .

With All My Gratitude

First, a big thank-you to the intrepid teachers and librarians who invite us to explore the past and imagine our possible futures. I am profoundly grateful to the many people who helped bring this book into being. Rubin Pfeffer faced unexpected challenges on this book’s journey with unstinting grace and wit. He has been a genuine inspiration to me. Amy Thrall Flynn has been a generous and patient guide, as well as a friend. My deepest gratitude to my dedicated editor, Carter Hasegawa, whose breadth and depth of cultural knowledge and sensitivity made revision feel like flow. All my thanks to the fabulous team at Candlewick Press and those working with them, including Hannah, Stephanie, Dana, Sasha, Nicole, Elise, Nathan, and everyone else I wish I had the space to include your name. You gave my book the best home, and your warm welcome during my visit was unforgettable. My heartfelt gratitude for the timely and invaluable assistance of Alison Hall, Gail Bloom, and Lainey Cameron, whose advice to use my joy filter touched me at just the right moment.

Archivists and biographers were vital to this journey. I’m grateful to those at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University, where I saw Hurston’s handwritten draft of Their Eyes Were Watching God —and the many crossed-out passages in Tell My Horse ! Seeing those pages sparked my imagination. Were the redactions made because Zora was afraid of the repercussions her research might have, or did she fear for those left behind, like Lucille? Thank you to the Guggenheim Foundation archives for mailing copies of Zora’s correspondence. At the Fashion Institute of Technology, director Valerie Steele kindly showed and let me touch the kind of clothing my characters would be wearing. Thank you to Zora’s biographer, the late Valerie Boyd. She graciously responded to my emails, as did Lucy Anne Hurston, Zora’s niece.

Thank you, Lucille, for inviting me to unearth your life, and Zora, for trying to support yourself as an author, which remains a challenge today. I still recall the thrill of discovering Jamaica Kincaid’s “Girl” in the New Yorker and thinking, How did she do that? When I was in college, Alice Walker inscribed my copy of In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens with one word underlined three times in purple ink: Be! Toni Morrison told me to “stay the course.” The best advice is often the hardest to follow.

Thank you to my early readers and supporters, including Cristina Garcia, Breena Clarke, and A.J. Verdelle. Elizabeth George, the mystery writer best known for her Inspector Lynley series, awarded me a grant from her foundation and later funded a fellowship that allowed me to attend a low-residency master of fine arts program. Thank you to all the students and faculty of the MFA program at the Northwest Institute of Literary Arts, which is unfortunately now shuttered. It was a joy to learn from David Wagoner, Kathleen Alcalá, Carolyn Wright, and Bruce Holland Rogers. The extraordinary Edwidge Danticat, a MacArthur Fellow, served as my thesis adviser and later selected an excerpt from my MFA thesis for her anthology Haiti Noir . Her encouragement and generosity over the years, and her brilliant work, including her historical novel The Farming of Bones , have all helped me more than I can say. The same is true of Tananarive Due, award-winning author, professor, screenwriter, and executive producer of the documentary film Horror Noire . I thank whoever assigned us as roommates for our New York Times summer internship!

I am deeply grateful to invaluable organizations helping writers in this challenging publishing landscape, such as the Authors Guild. The Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators helped me cross the bridge with its regional chapter and webinars and by awarding me a scholarship to its unforgettably inspiring annual conference. A big thank-you to George Brown and the Highlights Foundation family. Thanks to a scholarship, my manuscript found its shape at a Whole Novel Workshop led by Ashley Hope Pérez, author of the historical young adult novel Out of Darkness , one of the most challenged and banned books in the United States. It was also at Highlights that the ebullient novelist and workshop leader Nicole Valentine read my very rough draft revisions and offered lucid suggestions, as well as remarkable kindness.

Thank you to Kip Wilson, Jeannine Atkins, Cordelia Jensen, and Lyn Miller-Lachmann, who led me to discover the powerful beauty of the verse novel. Emma Dryden showed me the potential of returning to a manuscript I’d considered abandoning. Lesléa Newman’s loyalty, encouragement, friendship, and editorial acumen helped me reach the finish line, in the shadow of grief. Marilyn Nelson encouraged me to not play it safe. My mentorship with the exceptionally big-hearted Stacey Lee—thanks to We Need Diverse Books, which helped me write this new chapter of my life with both this mentorship and a grant for a summer working at Serendipity Literary Agency with Regina Brooks—gave me a compass to navigate challenges I didn’t know were coming. And Stacey never once complained about our nine-hour time difference, which made our FaceTime calls feel like pajama parties!

Artist communities are sanctuaries that balance the gathering of kindred spirits with the need for solitary musing. I’m deeply grateful for the grants, fellowships, residencies, and other supports I found for this novel as it was taking shape. Among the groups that provide support are Hedgebrook, Norcroft, Ragdale, Vermont Studio Arts Center, Atlantic Center for the Arts, the Squaw Valley workshops, Villa Dora Maar, the Chateau de Lavigny, Under the Volcano, Key West Literary Seminars, the Studios of Key West, and the Betsy Writer’s Room. Thank you to my friends in Key West, especially Ros, Joyce, and Kris. Also in Key West, whenever I see the iconic Judy Blume, a longtime advocate for our freedom to read and a co-owner of Books & Books, I’m reminded of why we persist. Bethany Hegedus and the wonderful team at the Writing Barn and Courage to Create gave me a chance to share what I’ve learned on this journey.

This would not be historical fiction without the history. I had help from the best, including novelist Madison Smartt Bell. Professor Yveline Alexis graciously shared her impressive expertise and pointed me in new directions that helped me deepen the novel in unexpected ways. Thank you to Professor Patrick Bellegarde-Smith for sharing his photos of family and of Haiti’s iconic gingerbread houses and to Professor Grace Sanders Johnson for introducing me to the roots of Haiti’s feminist movement. Professor Brandon R. Byrd was also generous with his knowledge. A big thank-you to the Haitian Studies Association for too many reasons to list, among them a revelatory screening of The Forgotten Occupation , directed by Alain Martin.

My novel was also sparked by contemporary figures, such as the courageous activist Chavannes Jean Baptiste, whose advocacy for disempowered small farmers in Haiti earned him the Goldman Environmental Prize. It was a privilege to help support his activism with the Mouvement Paysan Papaye. My admiration continues to grow for the students, faculty, and staff of the Haitian Education Leadership Program, which fights Haiti’s brain drain with the country’s largest college scholarship program. Thank you to Conor, Sam, and Ian, who helped me establish a scholarship in memory of my mother, Claudette, for young Haitian women. Chapo to Berchie, our first scholar, whose own words about her own remarkable journey radiate fierce hope from which we can all learn. Thank you to Chancellor Emeritus Charlie Nelms and his wife, Jeanetta. Professor Nelms has been an avid supporter of the scholarship fund, a valued friend, mentor, and role model. It has been an honor to collaborate with him across the years.

I’m extremely thankful for my friends, extended family, and allies, including Abby, Suzanne, Erika, Dan, David, Carmen and her late husband Juan, Carole and John, Barry, Bob, Philippe, Dennis, Simon, Efi, Mayra, Shelley, and all of my fabulous cousins, nieces, aunts, uncles, godparents, and other members of our marvelous family. Tonny’s support has been especially generous. Although we live far from each other, we remain close in spirit. Thank you to my brother Didier “Ed” Pinede. He is a devoted dad, voracious reader, walking sports encyclopedia, and, like our mother, a riveting storyteller.

I doubt I would have completed this novel without the abiding love of my husband, Erick, who helped lift me at my lowest points. His love of music and his curiosity as a scientist are matched by his keen editorial eye and sense of humor. Our beloved Hoosier cats and our Flemish dog remind us every day to savor the joys of the present moment, even as I confront fibromyalgia and other invisible disabilities. My pain mentors, Frida Kahlo and Octavia Butler, continue to inspire me with their boldness and courage.

I’m grateful to my ancestors, including those who have joined them this past decade, especially my mother and my father, Edouard. He linked his passion for music with pioneering creativity as an engineer in the same way my mother joined her passion for stories and for poetry, which she could recite by heart, with her teaching, service, and faith. I am still dazzled by the beauty of the letter my father wrote in French asking for my mother’s hand in marriage, and I return often to the wisdom of a letter he wrote me about perfectionism. My mother’s enthralling stories of Haiti and her grandmother, Grandmè Mimise, inspired this novel.

My parents shared an exceptional zest for life, whose roots I witnessed in their homeland. Dèyè mòn, gen mòn, is one of Haiti’s most well-known proverbs. Beyond mountains are mountains. Thank you to those who remain undaunted by the climb, guided by justice and compassion. Kenbe. Thank you to those who came before and who dreamt us into being. You made this possible, and I carry you with me. Mèsi anpil.

Fullepub

Fullepub