Viv

Fell, New York

August 1982

VIV

Coming here was an accident. A detour sent her bus into Pennsylvania, and from there she hitched, trying to save cash. The first ride was only going to Binghamton. The second ride told her he was going to New York, but an hour later she realized he was driving the wrong way.

“We’re not going to New York,” Viv said to the man. “We’re driving upstate.”

“Well,” the man said. He was in his forties, wearing a pale yellow collared shirt and dress pants. He was clean-shaven and wore rimless glasses. “You should have been more clear. When you said New York, I thought you meant upstate.”

She’d been clear. She knew she had. She looked out the window at the setting sun, wondering where he was taking her, her heart starting to accelerate in panic. She didn’t want to be rude. Maybe she should be nice about it. “It’s okay,” she said. “You can let me out here.”

“Don’t be silly,” the man said. “I’ll bring you to Rochester, where I can at least get you a meal. You can get a bus from there.”

Viv gave him a smile, like he was doing her a favor, driving her away from where she wanted to be. “Oh, you don’t need to do that.”

“Sure I do.”

They were on a two-lane stretch of road, and she saw the sign for a motel ahead. “I need to stop for the night anyway,” she said. “I’ll just stay here.”

“That place? Looks sketchy to me.”

“I’m sure it’s fine.” When he didn’t speak, she said, “I don’t mean to be a bother.”

Her throat went dry as the man pulled over. She thought she might throw up. She couldn’t have said what she was afraid of, what made her so relieved that he did as she asked. What else would he have done? she chided herself. He was probably a nice man and she was being ridiculous. It came from being on the road alone.

Still, once he stopped the car she opened the door, putting one foot on the roadside gravel. Only then did she turn and get her bag from the back seat. The entire time she had her back to him, she held her breath.

When she had finished wrestling the bag into her lap, she felt something warm on her thigh. She looked down and saw the man’s hand resting there.

“You don’t have to,” he said.

Viv’s mind went blank. She mumbled something, pulled out from under his hand, got out of the car, and slammed the door. The only words she could manage—spoken as the car pulled away, when the man couldn’t hear her—were “Thank you” and “Sorry.” She didn’t know why she said them. She only knew that she stood at the side of an empty road, in front of an empty motel, her heart pounding so hard it felt like it was squeezing her chest.

Back in Grisham, Illinois, Viv was the problem daughter. After her parents’ divorce five years earlier, she couldn’t seem to do anything right. While her younger sister obeyed the rules, Viv did everything she wasn’t supposed to: skipping school, staying out late, lying to her mother, cheating on tests. She didn’t even know why she did it; she didn’t want to do half of those things. It sometimes felt like she was in someone else’s body, one that was angry and exhausted in turns.

But she did all the things that made her bad, that made her mother furious and embarrassed. One night, after she’d been caught coming home at two in the morning, her panicked mother had nearly slapped her. You think you’re so damned smart, her mother had shouted in her face. What would you do if you ever saw real trouble?

Now, standing on the side of a lonely road far from home, with the man’s taillights vanishing in the distance, those words came back. What would you do if you ever saw real trouble?

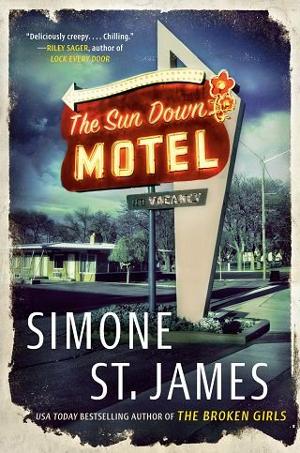

The August sky was turning red, the lowering sun stinging her eyes. She wore a sleeveless turquoise top, jeans with a white and silver belt, and tennis shoes. She hefted her bag on her shoulder and looked up at the motel sign. It was blue and yellow, the words SUN DOWN in the classic old-style kind of letters you saw from the fifties and sixties. Underneath that were neon letters that probably lit up at night: VACANCY. CABLE TV!

Behind the sign was a motel laid out in an L shape, the main thrust leading away from the road, the foot of the L running parallel to it. It had an overhang and a concrete walkway, the room doors lined up in the open air. An unremarkable place decorated in dark brown and dirty cream, the kind of place people drove by unless they were desperate to sleep. At the joint of the L was a set of stairs leading to the upper level. There was only one car in the parking lot, parked next to the door nearest the road that said OFFICE.

Viv wiped her forehead. The adrenaline spike from getting away from the man in the car was fading, and she was tired, her back and shoulders aching. Sweat dampened her armpits.

She had twenty dollars or so—all the cash she had left. She had a bank account with savings from her job back home at the popcorn stand at the drive-in, plus her small earnings from modeling for a local catalog. She’d stood in front of a camera for an afternoon wearing high-waisted acid-wash jeans and a bright purple button-down blouse, placing her fingertips into the pockets of the jeans and smiling.

Her entire savings totaled four hundred eighty-five dollars. It was supposed to be New York money, the money that would send her to her new life. She wasn’t supposed to spend it before she even got anywhere. Yet like everything else about this trip so far, she seemed to have miscalculated.

This didn’t look like an expensive place. Maybe twenty dollars would get her a bed and a shower. If not, maybe there was a way to sneak into one of the rooms. It didn’t look like anyone would see.

Viv approached the office door and put her hand on the cold doorknob. Somewhere far off in the trees, a bird cried. There was no traffic on the road. If the guy on the other side of this door looks like Norman Bates, she told herself, I’m turning around and running. She took a deep breath and swung the door open.

The man inside did not look like Norman Bates—it wasn’t a man at all. It was a woman sitting on a chair behind an old desk. She was about thirty, lean and vital, with brown hair in a ponytail and a face that had hard lines. She was wearing a baggy gray sweatshirt, loose-fit jeans, and heavy brown boots, which Viv could see because she had them propped right up on the desk. She was reading a magazine but looked up when the door opened.

“Help you?” the woman said without moving her feet off the desk.

Viv put her shoulders back and gave the woman her catalog-model smile. “Hi,” she said. “I’d like a room, but I only have twenty dollars in cash. How much is it, please?”

“Usually thirty,” the woman said without missing a beat or changing her pose. The magazine was still at chin height. “But I’m the owner and there’s no one else here, so I’m not going to turn down twenty bucks.”

Feeling a rush of triumph, Viv put her twenty-dollar bill down on the desk. And waited.

The woman still didn’t move. She didn’t put down her magazine, and she didn’t take the twenty. Instead her gaze moved over Viv. “You passing through, honey?” she said.

It seemed a safe enough question. “Yes.”

“Is that so? I didn’t hear a car.”

Viv shrugged, trying for vacant and harmless. Most people fell for it.

The woman finally closed the magazine and put it on her jean-clad lap. “Were you hitching on Number Six?”

“Number Six?” Viv said, confused.

“Number Six Road.” The woman’s eyebrows lowered. “If I was your mother, I would tan your hide. Hitching on that road is dangerous for lone girls.”

“I didn’t. My ride just dropped me off here. He picked me up outside Binghamton. I was heading for New York.”

“Well, honey, this isn’t New York. This is Fell. You’re going the wrong way.”

“I know.” Viv wished the woman would just give her a room. She needed to put her heavy bag down. She needed a shower. She needed something to eat, though without the twenty she didn’t know how she would pay for it. She pointed to the big book sitting open on the desk, obviously a guest registry. “Should I write my name in there?” Then, her suburban Illinois good-girl training coming through: “I can pay you the thirty if I can just get to a bank tomorrow. But they’re all closed now.”

The woman snorted. She tossed the magazine—Viv saw that it was People, with Tom Selleck on the cover—onto the desk and finally swung her feet down. “I have a better idea,” she said. “My night guy just quit. Cover the desk tonight and keep your twenty bucks.”

“Cover the desk?”

“Sit here, answer the phone. If someone comes in, take their money and give them a key. Keys are here.” She opened the desk drawer at her right hand. “Have them sign the book. That’s it. You think you can do that?”

“You don’t have anyone else to do it?”

“I just said my guy quit, didn’t I? I’m the owner, so I should know. Either you sit at this desk all night or I do. I already know which one I’d rather it be.”

Viv blew out a breath. The work itself didn’t bother her; she’d worked plenty of service jobs back in Illinois. But the idea of staying awake all night didn’t sound very fun.

Still, if she did it she held on to her twenty. Which meant she could eat something.

She glanced around the office, looking for a signal that there was a catch, but all she saw was bland walls, a desk, a few shelves, and the window on the office door. There was the muffled sound of a car going by on the road, and the sky was getting darker. Surprisingly, Viv smelled the faint tang of cigarette smoke from somewhere. It was sharp and burning, not the old-smoke smell that could come from the woman’s clothes. Someone was smoking a cigarette nearby.

For some reason, that made her feel a little better. There was obviously someone in this place, even if she couldn’t see them.

“Sure,” she told the woman. “I’ll work the night shift.”

“Good,” the woman said, opening the desk drawer and tossing a key on the desk. “Room one-oh-four is yours. Wash up, have a nap, and come see me at eleven. What’s your name?”

That smell of smoke again, like whoever it was had just taken a drag and exhaled. “Vivian Delaney. Viv.”

“Well, Viv,” the woman said, “I’m Janice. This is the Sun Down. Looks like you’ve found yourself somewhere to stay.”

“Thank you,” Viv said, but Janice had already gone back to Tom Selleck, putting her boots on the desk again.

She picked up the key and her twenty and left, pushing open the office door and stepping onto the walkway. She expected to see the smoker somewhere out here, maybe a guest having a smoke in the evening air, but there was no one. She walked out onto the gravel lot, turned in a circle, looking. In the lowering light of dusk the motel looked shuttered, no light coming from any of the rooms. The trees behind the place made a hushing sound in the wind. There was the soft sound of a shoe scraping on the gravel in the unlit corner of the lot.

“Hello?” Viv called, thinking of the man who’d put his hand on her leg.

Nothing.

She stood in the lowering darkness, listening to the wind and her own breathing.

Then she went to room 104, took a hot shower, and lay on the bed, wrapped in a towel, staring at the blank ceiling, feeling the rough comforter against the skin of her shoulders. She listened for the sounds you usually heard in hotels—footsteps coming and going, strangers’ voices passing outside your door. Human sounds. There were none. There was no sound at all.

What kind of motel was this? If it was this deserted, how did it stay open? And why did they need a night clerk at all? At the movie theater, the manager had sent everyone home at ten because he didn’t want to pay them after that.

She wasn’t getting paid, not exactly. But it would still be easier for Janice to turn the lights out, lock the office door, and go home instead of trying to find someone to sit there all night.

Her feet ached, and her body relaxed slowly into the bed. Lonely or not, this was still better than hitching on that dark highway, hoping for another stranger to pick her up. She started to hope there was a vending machine somewhere in the Sun Down, preferably one with a Snickers bar in it.

The man in the yellow collared shirt had put his hand on her thigh like it belonged, like they had an agreement because she was in his car. He’d curled his fingers gently toward the inside of her thigh before she pulled away. She felt that jolt in her gut again, the fear. She’d never felt fear like that before. Anger, yes. And she’d slept a lot since her parents’ divorce, sometimes until one or two in the afternoon, another thing that made her mother yell at her.

But the fear she’d felt today had been deep and sudden, almost like a numbing blow. For the first time in her life, it occurred to her how erasable she was. How it could all be over in an instant. Vivian Delaney could vanish. She would simply be gone.

I’m afraid, she thought.

Then: This seems like the right place for it.

She was asleep before she could think anything else.

Fullepub

Fullepub