Carly

Fell, New York

November 2017

CARLY

This place was unfamiliar.

I opened my eyes and stared into the darkness, panicked. Strange bed, strange light through the window, strange room. I had a minute of free fall, frightening and exhilarating at the same time.

Then I remembered: I was in Fell, New York.

My name was Carly Kirk, I was twenty years old, and I wasn’t supposed to be here.

I checked my phone on the nightstand; it was four o’clock in the morning, only the light from streetlamps and the twenty-four-hour Denny’s shining through the sheer drapes on the hotel room window and making a hazy square on the wall.

I wasn’t getting back to sleep now. I swung my legs over the side of the bed and picked up my glasses from the nightstand, putting them on. I’d driven from Illinois yesterday, a long drive that left me tired enough to sleep like the dead in this bland chain hotel in downtown Fell.

It wasn’t that impressive a place; Google Earth had told me that much. Downtown was a grid of cafés, laundromats, junky antique stores, apartment rental buildings, and used-book stores, nestled reverently around a grocery store and a CVS. The street I was on, with the chain hotel and the Denny’s, passed straight through town, as if a lot of people got to Fell and simply kept driving without making the turnoff into the rest of the town. The WELCOME TO FELL sign I’d passed last night had been vandalized by a wit who had used spray paint to add the words TURN BACK.

I didn’t turn back.

With my glasses on, I picked up my phone again and scrolled through the emails and texts that had come in while I slept.

The first email was from my family’s lawyer. The remainder of funds has been deposited into your account. Please see breakdown attached.

I flipped past it without reading the rest, without opening the attachment. I didn’t need to see it: I already knew I’d inherited some of Mom’s money, split with my brother, Graham. I knew it wasn’t riches, but it was enough to keep me in food and shelter for a little while. I didn’t want numbers, and I couldn’t look at them. Losing your mother to cancer—she was only fifty-one—made things like money look petty and stupid.

In fact, it made you rethink everything in your life. Which in my crazy way, after fourteen months in a fog of grief, I was doing. And I couldn’t stop.

There was a string of texts from Graham. What do you think you’re doing, Carly? Leaving college? For how long? You think you can keep up? Whatever. If all that tuition is down the drain, you’re on your own. You know that, right? Whatever you’re doing, good luck with it. Try not to get killed.

I hit Reply and typed, Hey, drama queen. It’s only for a few days, and I’m acing everything. This is just a side trip, because I’m curious. So sue me. I’ll be fine. No plans to get killed, but thanks for checking.

Actually, I was hoping to be here for longer than a few days. Since losing Mom, staying in college for my business degree seemed pointless. When I’d started college, I’d thought I had all the time in the world to figure out what I wanted to do. But Mom’s death showed me that life wasn’t as long as you thought it was. And I had questions I wanted answers to. It was time to find them.

Hailey, Graham’s fiancée, had sent me her own text. Hey! You OK?? Worried about you. I’m here to talk if you want. Maybe you need another grief counselor? I can find you one! OK? XO!

God, she was so nice. I’d already done grief counseling. Therapy. Spirit circles. Yoga. Meditation. Self-care. In doing all of that, what I’d discovered was that I didn’t need another therapy session right now. What I really needed, at long last, was answers.

I put down my phone and opened my laptop, tapping it awake. I opened the file on my desktop, scrolling through it. I picked out a scan of a newspaper from 1982, with the headline POLICE SEARCHING FOR MISSING LOCAL WOMAN. Beneath the headline was a photo of a young woman, clipped from a snapshot. She was beautiful, vivacious, smiling at the camera, her hair teased, her bangs sprayed in place up from her forehead as the rest of her hair hung down in a classic eighties look. Her skin was clear and her eyes sparkled, even in black and white. The caption below the photo said: Twenty-year-old Vivian Delaney has not been seen since the night of November 29. Anyone who has seen her is asked to call the police.

This. This was the answer I needed.

I’d been a nerd all my life, my nose buried in a book. Except that once I graduated from reading The Black Stallion, the books I read were the dark kind—about scary things like disappearances and murders, especially the true ones. While other kids read J. K. Rowling, I read Stephen King. While other kids did history reports about the Civil War, I read about Lizzie Borden. The report I wrote about that one—complete with details about exactly where the axe hit Lizzie’s father and stepmother—got my teacher to call my mother with concern. Is Carly all right? My mother had brushed it off, because by then she knew how dark her daughter was. She’s fine. She just likes to read about murder, that’s all.

What my mother didn’t mention—what she hated to talk about at all—was that I came by it naturally. There was an unsolved murder in my family, and I’d been obsessed with it for as long as I could remember.

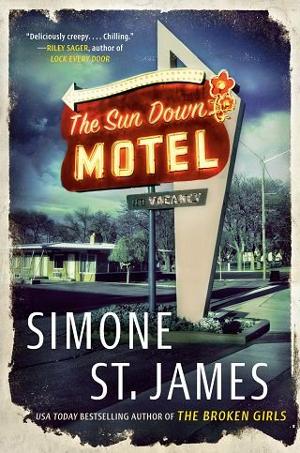

I looked at the newspaper clipping again. Viv Delaney, the girl in the photograph, was my mother’s sister. In 1982, she disappeared while working the night shift at the Sun Down Motel and was never found.

It was the huge, gaping hole in my family, the thing that everyone knew about but no one spoke of. Viv’s disappearance was a loss like a missing tooth. Never ask your mother about that, my father told me the year before he left us all for good. It upsets her. Even my brother, the eternal pain in the ass, was sensitive about it. Mom’s sister was killed, he told me. Someone took her and murdered her, like that guy with the hook. It creeps me out. No wonder Mom doesn’t talk about it.

Thirty-five years my aunt Viv had been missing. My grandparents—Mom and Viv’s parents—were dead. There were no pictures of Viv in our house, no mementos of her. The year before Mom died, when I was home for the summer, I’d found a story online and seen Viv’s face for the first time. I’d thought maybe enough time had passed. I’d printed the clipping out and gone downstairs to show it to her. “Look what I found,” I said.

Mom was sitting on the sofa in the living room, watching TV after dinner. She took the clipping from me and read it. Then she stared at it for a long time, her gaze fixed on the photograph.

When she looked back up at me, she had a strange look on her face that I’d never seen before and would never see again. Pain, maybe. Exhaustion, and some kind of old, rotted-over, carved-out fear. In that moment I had no idea that she had cancer, that I would lose her within a year. Maybe she knew then and didn’t tell me, but I didn’t think so. That look on her face, that fear, was all about Vivian.

Her voice, when she finally spoke, was flat, without inflection. “Vivian is dead,” she said. She put down the clipping and got up and left the room.

I never asked Mom about it again.

• • •It was only after Mom died that I got mad. Not at Mom, really—she was a teenager when Viv disappeared, and there wasn’t much she could have done. But what about everyone else? The cops? The locals? Viv’s parents? Why hadn’t there been a statewide search? Why had Viv been allowed to vanish into nothingness with barely a ripple?

The first person I asked was Graham, who was older and remembered more than I did. “Grandma and Granddad were divorced by then,” Graham said. “When Viv disappeared, Grandma was a single mother.”

“So? That meant she didn’t look for her daughter? Granddad, either?”

Graham shrugged. “Grandma didn’t have much money. And Mom told me that she and Viv used to fight all the time. They didn’t get along at all.”

I’d stared at him, shocked. We were sitting in my mother’s rental apartment, in the middle of boxing up her things. We were taking a break and eating takeout. “Mom told you that? She never told me that.”

My brother shrugged again, leaning back on a box and scrolling through his phone. “They didn’t have the Internet back then, or DNA. If you wanted to find a missing person, you had to get in your car and go driving around looking for them. Grandma couldn’t take time off work and go to Fell. And Granddad was already remarried. I don’t think he cared about any of them all that much.”

It was true. Mom hadn’t had a good relationship with her father, who had left their family to sink or swim. She hadn’t even gone to his funeral. “What about the cops, though?” I said.

Graham put his phone down briefly and thought it over. “Well, Viv had already left home, and she was twenty,” he said. “I guess they thought she’d just taken off somewhere.” He looked at me. “You’re really into this, aren’t you?”

“Yes, I’m really into this. They didn’t even find a body. It isn’t 1982 anymore. We have the Internet and DNA now. Maybe something can be done.”

“By you?”

Yes, by me. There didn’t seem to be anyone else. And now that Mom was gone, I could ask all the questions I wanted without hurting her feelings. Mom had taken all of her memories of Viv with her when she died, and I’d never hear them. My anger at that was helpless, something that the therapists and counselors said I needed to work through. But my anger at everyone else, my outrage that my aunt’s likely abduction and death were written off as just something that happened—I could work through that by coming to Fell and getting my own answers.

I clicked the other scanned article I had on my computer. It was headlined simply MISSING GIRL STILL NOT FOUND. The details were sketchy: Viv was twenty; she had been in Fell for three months; she worked at the Sun Down Motel on the night shift. She’d gone to work and disappeared sometime in the middle of her shift, leaving behind her car, her purse, and her belongings. Her roommate, a girl named Jenny Summers, said Viv was “a nice person, easy to get along with.” She was also described—by who was not cited—as “pretty and vivacious.” She had no boyfriend that anyone knew of. She was not into drugs, alcohol, or prostitution that anyone could tell. Her mother—my grandmother—was quoted as being “worried sick.”

She was a beautiful girl, gone.

On foot. Without any money.

Vivian is dead.

Viv’s case hadn’t received national or even statewide media attention. The local Fell newspapers weren’t digitized—they were still physically archived in the Fell library. When I started digging, all I found were true-crime blogs and Reddit threads by armchair detectives. None of the blogs or threads were about Vivian, but a lot of them were about Fell. Because Fell, it turned out, had more than one unsolved murder. For such a small place, it was a true-crime buff’s paradise.

The second article was in Mom’s belongings. I’d found it when I’d gone through her dresser after she died, tucked in an envelope in the back of a drawer. The envelope was white, crisp, brand-new. Written on the back, in Mom’s lovely handwriting, was: 27 Greville Street, apartment C.

Viv’s address, maybe? The piece of newsprint inside the envelope was nearly disintegrating, so I’d scanned it and added it to the first one I found.

Vivian is dead.

Mom had wanted no memories of her sister, no discussion of her, and yet she’d kept this article for thirty-five years, along with the address. She’d even put it in a new envelope sometime recently, recopied the address, which meant she’d at least pulled the article out of the old envelope, maybe read it again.

Viv was real. She wasn’t a spooky tale or a ghost story. She had been real, she had been Mom’s sister—and somehow, looking at that crisp white envelope, I knew she had mattered to Mom, a lot, in a way I had lost my chance to understand.

This was all I had: two newspaper articles and a memory of grief. Except now I had more than that. I had a little money and I had a very clear map from Illinois to Fell, New York. I had an address for Viv’s apartment, maybe, and the Sun Down Motel. I had no boyfriend and a college career I had no passion for. I had a car and so few belongings that they fit into the back seat. I was twenty, and I still hadn’t started my life yet. Just like Viv hadn’t.

So I’d left school—Graham really was blowing this out of proportion—and got in my car for a road trip. And here I was. I’d look around town and dig up the local articles in the library. I’d go see the Sun Down for myself, since my Internet search said it was still in business. Maybe someone who lived here had known Viv, remembered her, could tell me about her. Maybe I could make her more than a fading piece of newsprint hidden in my mother’s drawer. Her disappearance was the big mystery of my family—I wanted to see it firsthand, and all it would cost was a few days out of school.

Try not to get killed.That was my big brother, trying to scare me. It wasn’t going to work. I didn’t scare easily.

Still, I closed my laptop and tried not to think about someone hurting the girl I’d seen in the photo, someone grabbing her, taking her somewhere, doing something to her, killing her. Dumping her somewhere lonely, where maybe she still was. Maybe she was only bones now. Maybe that person, whoever they were, was dead now, or in prison. Maybe they weren’t.

Vivian is dead.

It wasn’t fair that Vivian was forgotten, reduced to a few pieces of newsprint and nothing else. It wasn’t fair that Mom had died and taken her memories and her grief with her. It wasn’t fair that Viv didn’t matter to anyone but me.

I was in Fell. I didn’t belong here. I had no idea what I was doing.

And still I waited, without sleeping, for the sun to come up again.

Fullepub

Fullepub