Chapter 3

I wake up in a ten-thousand-square-foot, concrete-and-glass monstrosity in Point Dume. It’s the last house on the block, butted up against the nature preserve, so if you step through the sliding back doors and look left, there’s just scrub grass and ocean to the ends of your eyeballs. It has a gated driveway, a manicured lawn with stone steps down to a private beach, a chef’s wet dream of a kitchen that’s never been cooked in. It’s a gilded fortress. It is, of course, my mother’s house.

No place for children, is how Laz always described it—usually with a highball glass in hand, sun hitting his green eyes as he perched on the back patio. I have this perfect memory of him in white linen pants, framed by Camilla’s infinity pool. He’d walk across the street from his house for afternoon drinks, every bit as groomed as he was at last night’s show, though his only audience, those days, was my mother.

He’d say this in front of me, that the home she’d made was not intended for me. I knew it already; it was impossible not to know—the house had a meditation studio, an infrared sauna, blown-glass objets d’art scattered like so many seedlings. But no place for me to keep my brightly colored chapter books, and no snacks in the pantry unless I wanted raw almonds, which I didn’t. My dad’s apartment in Venice still had my first-grade drawings taped to the refrigerator. Taped, because it wasn’t magnetic. And still there, maybe, because he so rarely was. But at Camilla’s house I’d always known to make myself small and neutral enough to creep chameleon-like through her monochrome rooms.

The only color in the house is the sea; every room was designed to let it in. The entire back wall is glass from floor to ceiling, like we’re in a display case for the ocean to observe. This morning the water is a moody blue, shadows moving across it like specters cast from the clouds. Rain today, maybe.

I’ve been watching the ocean since before the sun rose above it, tracking its churning waves from black to navy. It’s light enough now that the room around me has come into focus: last night’s floral dress draped over the desk chair, my phone screen-side-down on the cold marble nightstand, the frayed edge of a book just peeking from my open backpack on the floor.

I stare at the only visible triangle of its cover until my eyes blur. A physical reminder, incontestable, of the last thing I did before flying to Los Angeles. The same thing I always do.

I went searching for my mother in the one place I can always find her: the airport bookstore.

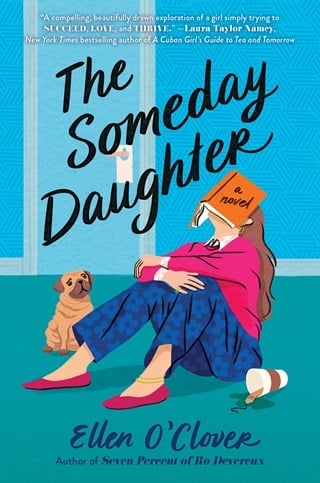

Sometimes she winds up in SELF-HELP, but usually she lands in the broader NONFICTION. Often at the back of the store, past all the new hardcover fiction and the spinning shelves of airplane neck pillows. Finding her in airports is more of a compulsion than a choice, something I always do before flights, like a nervous tic or maybe a good luck charm. There have been a couple of times over the years I couldn’t track her down—in the Jackson Hole airport when I met my dad for Christmas sophomore year, or during one never-ending layover in Des Moines. But almost always, tucked between the Rs and the Ts, there she is. Camilla St. Vrain: Letters to My Someday Daughter.

It’s a thin book, which probably factored into its popularity. One hundred and twenty pages, easy to rip through on a cross-country flight or a long afternoon at the pool. The book’s newer editions have a subtitle, added by her publisher after a few years: Rewriting Your Inner Narrative Through the Transformative Power of Kindness. Most versions have Camilla’s face on the cover, frozen in time at twenty-nine, when the book was published and became an instant bestseller. She’s wearing a blazer in the photo, its lapels framing her flat, gold necklace. Under the picture: Camilla St. Vrain, PsyD.

I’ve heard her explain the book’s philosophy hundreds of times—often enough to wear it like a tattoo on the inside of my forehead, often enough that I can pull up the words from nothing.

Ladies, she always begins. Let’s stop being so mean to ourselves, shall we? Let’s change that little voice inside that tells us we’re unworthy. Let’s each of us speak to ourselves as if we’re someone innately deserving of kindness. Someone we’re obligated to protect, to convince that the world is beautiful and good. Someone like our own hypothetical someday daughters.

Of course, I wasn’t around back then. Camilla didn’t have me for another seven years; when she wrote the book, she had no idea how to talk to a daughter. But millions of women ate it up. My mother was so successful at writing about being a therapist that she didn’t need to actually be one anymore. Her fans were loyal and hell-bent on bettering themselves; she did speaking tours, book clubs, conferences. She changed people’s lives, or at least that was the claim.

And here I’ve always been, the real daughter Camilla St. Vrain holds at arm’s length, like a tissue you’ve trapped a house spider inside. Something to be contained and feared until you can get it to the trash can.

They had three copies at Denver International, two hardcovers and one paperback with a neon USED sticker half-covering the title. The airport was test-driving a new trade-in program: buy a book at the start of your vacation and return it to another airport at the end for half your money back. The next day, I knew, there would be twenty-fifth-anniversary editions on those same shelves, smelling of fresh-cut paper and sporting a film-grain photograph of Camilla and me on my fourth birthday. The next day I would be in Los Angeles to begin an entire summer promoting it with her.

I pulled the used copy of Letters off the shelf. It was a first edition, no subtitle, just the title written out in self-confident capitals. When I cracked it open to a middle page, the margins were full of annotations, someone’s reactions and reminders and starred sentences left there for anyone to find.

I glanced up instinctually, breathing through a hot flush of secondhand embarrassment. Who would return something like this? I flipped to another page, where the reader had underlined We are the determiners of our own self-talk. How mortifying to take this book so seriously you’d mark it up for yourself, save a sentence like that.

I snapped it shut, took it over to the register. Bought it for $6.79.

Ethan was waiting for me between our gates, thick textbook splayed open in front of him on a high-top table halfway inside a coffee shop and halfway into the terminal.

“Find anything good?” he asked, looking up as I pulled out the chair across from him. But I’d already buried the book between folded jeans in my suitcase, hidden it from the world just like everything else about my relationship with Camilla.

“No,” I said, accepting the coffee he nudged toward me. “It’s all tabloids and beach reads in there.”

“Mmm,” he said softly, and tucked his chin to turn back to the textbook. We’d graduated the day before, me with the Ss and Ethan with the Ws, wearing matching black robes and gold-tasseled caps. He was flying to Pennsylvania, where we should have been going together. Already studying for the summer premed intensive we were both accepted to back in March. His family was tucked away at their gate, giving us the privacy of one last hour together before we parted for a summer that was supposed to be spent side by side. Camilla, of course, had taken a red-eye back to LA after the ceremony.

“This is interesting,” Ethan said. He looked up at me, then spun the textbook so I could read it right side up. “The first unit’s on biomedical ethics, and they’re talking about this case study from the seventies, this man who presented with thoracic pain....”

His eyes were on the book, pointing me through a diagram. But I just watched him: dark lashes through his square-framed glasses, the soft lines of his pale cheeks, the cut of his shirt collar. He smelled like piney deodorant and the fancy Kiehl’s soap his mom always sent in her care packages—the familiar way he’d always smelled, since we met in junior English when we were paired up for our midterm assignment.

We were supposed to take turns verbally arguing our thesis angles for Frankenstein, work out the kinks before putting pen to paper. Ethan told me that Frankenstein was Shelley’s reaction to the body horror of giving birth and losing her baby, herself the motherless daughter of a woman who died in childbirth. I stumbled through an argument that I knew wasn’t nearly as compelling, feeling like a fool until he intercepted me on the steps of the humanities building after class and asked if I wanted to join forces. That’s exactly how he said it, too. Join forces. He meant, did I want to go on a date. He was wearing a burgundy cabled sweater and those same thick-framed glasses, his teeth perfect white and braces-straight. I almost couldn’t believe my good fortune that this person thought I was his match.

We spent the year and a half after that editing each other’s papers, holding up flash cards for one another on our favorite couch in the library. He became a student EMT because I was one, too, and when our shifts overlapped, we sat up together in the student center with our navy-blue uniforms on, watching old movies on his laptop. Ethan came from a family of New York lawyers and wanted to be a neurologist. I came from my mother and wanted to be a real doctor in the way she was not.

We chose the summer course at UPenn because it was the obvious option: a résumé-builder that kept us together for the last few months before college. Ethan is going to Yale, and I’ll be at Johns Hopkins—a fewer-than-five-hour drive for weekend visits. But for just a little while longer, he was right there across from me: steady, reliable Ethan. Poised over a textbook to share something he knew I would care about, because he’s the one person who always knows.

I took a breath. I took a minute to mourn what Camilla had stolen from me.

Fullepub

Fullepub