Chapter 2

The alley behind the theater smells like hot garbage. When I spill sideways through the metal door, my foot lands in something wet enough to splash me, though this is Los Angeles and it hasn’t rained in weeks. Horrifying. I suck in a lungful of trash air and collapse against the door as it whooshes shut, zipper pull promptly gouging my spine.

It’s muggy as murder out here, moon rising over the smog haze of downtown LA. Inside, my mother is doing damage control. Magnolia is probably on a rampage already, hunting me down one hallway at a time. I’ve got maybe thirty more seconds to myself, so I smash my eyes shut and start counting my fingers.

Thumb to pinky, thumb to ring finger, thumb to middle, thumb to index. I repeat it quickly, over and over, counting out loud.

“One, two, three, four.” Breath of disgusting air. “Five, six, seven, eight.” Another breath, and a steadying swallow. “Nine, ten, ele—”

“What are you doing?”

For a moment, I don’t move. I stand suspended—hand lifted in front of me, tips of my thumb and middle finger pressed together, zipper pull lodged into my skin—like maybe if I don’t open my eyes, I’ll still be alone.

But then the voice comes again, a pointed little cough. I open my eyes and lower my hand.

“Conjuring a spirit?” I can only see half the guy’s face, one knee jutted into the yellow cast of a streetlamp. He’s leaning against a dumpster, and moves even farther into the light to get a better look at me. “Don’t let me stop you, if so.”

“I’m clearly not conjuring a spirit.” My voice is as acrid as the garbage keeping us company back here. The last thing I need, after being paraded like a prize calf by my mother, is some stranger joking around with me in a trash pit.

The guy steps into the glow of the streetlamp and, finally, I place him: one of the interns staffing the tour. I saw him backstage before the reading, huddled over an enormous video camera.

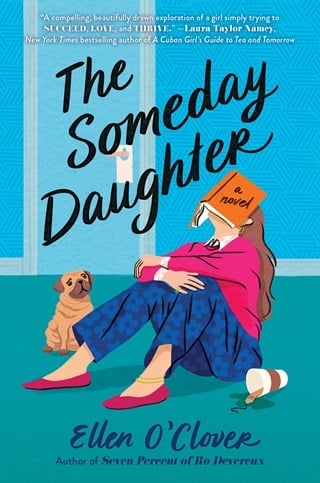

“Not super clear,” he says. His hair is dark and curly, tied at the nape of his neck with a few pieces shaken loose to scrape his jaw. It makes him look like some kind of colonial pilgrim. Or Tarzan. “I didn’t realize magic would be part of the show.” He tips his head toward the theater’s giant marquee, just visible at the end of the alley: Camilla St. Vrain: “Letters to My Someday Daughter” Anniversary Tour.

“It’s not magic.” I reach for the zipper, trying to twist it so it isn’t jutting into me. “It’s a centering practice.” I can’t quite reach, and I spin so my back is facing him. “Can you help me with this?”

Silence. I glance over my shoulder, and he’s watching me with his eyebrows raised. “What?” I say.

“Do you need to be naked for the next phase of the conjuring?”

“I don’t need to—” He’s smiling when I turn around, lopsided and easy-looking, one crooked canine visible in the dim light. “I’m sorry, what are you doing back here?”

He huffs half a laugh. “I’m not answering until you tell me what a centering practice is.”

“I don’t need to explain myself to you.” And I certainly don’t need to explain my finger counting, the habit I haven’t quite been able to break, the quickest way to calm myself down when I’m worked up—by my mother, by her demands of me, by anything. “Just help me with the zipper.”

I turn back around, hands on my hips. For a moment there’s nothing—just the hot, motionless air and the distant honks of evening traffic. Then I feel fingertips on my back, cool and light, and finally—finally—relief from the zipper. The guy takes two steps away from me before speaking again.

“That was rough in there.”

I straighten, smoothing my hands over the floral skirt as I turn back to face him. “I don’t know what you mean.”

“Really,” he says flatly. I don’t like how he’s looking at me, like I just showed all my cards and have no way to clutch them back to my chest now. “So it’s typical for you to flee mid-event like you just remembered you left your flat iron plugged in?”

I feel my face scrunch into itself, rake my eyes over his dark hair. “What would you know about leaving a flat iron plugged in?”

“Little sister.” He lifts his phone, dark-screened in the space between us. “I’m out here because she called.”

My own phone buzzes in the depths of my dress, and I reach into the frills to find it.

ETHAN WOOD: How’d it go?

His name is enough to make me remember: I need to get out of here.

“Look,” I say, glancing up, “um—”

“Silas,” he supplies, watching me patiently. As if it doesn’t smell like a landfill on fire back here, as if he has all the time in the world.

“Silas,” I repeat. I gesture at myself. “Audrey. I’ve—”

“I know who you are.”

I wince. “Right. I’ve got to go.”

“Where?” he asks, glancing toward the dark end of the alley. There’s a town car waiting there, sleek black and sleeping, ready to whisk my mother away. “Driver’s still inside.”

“No,” I say. I open my phone to call a rideshare and in my peripheral vision, Silas shifts. “Like, go go. Go home.”

“To Colorado?”

I look up at him. I shouldn’t be surprised when people do this, when they’ve read enough of Camilla’s Wikipedia page to see where she sent me to school. But still, it grates: I don’t know this person at all, but somehow he knows where home is to me. I don’t answer, just look back down at my phone and start to call a car.

“Hey, don’t,” Silas says. Our eyes meet, and there’s something there—like this matters to him. “We’re just getting started.”

The Letters to My Someday Daughter tour has barely begun. There are nine more cities to visit, eight more weeks of travel, so much more money for my mother to make. And yet.

“I’m leaving.”

“No.” An icy voice rises from behind us, and there she is: Magnolia Jones herself, haloed in the light from the doorframe. My mother’s assistant, and the most tenacious woman to walk the earth in four-inch stilettos. “You most certainly are not.”

Fullepub

Fullepub