Chapter 10

10

TWO DAYS LATER

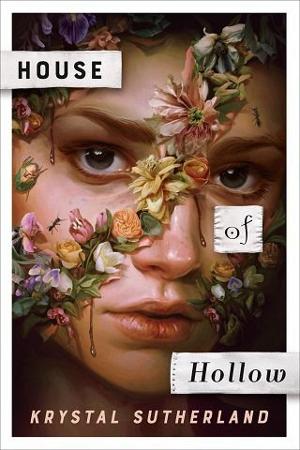

Another flash wentoff, leaving a new cluster of sticky white spots in my vision. I looked down at my dress and tried to blink them away. A thread was coming loose at the hem. I picked at it, watching the stitching come undone as I pulled. It was a House of Hollow piece taken from Grey’s closet. We’d all dressed in House of Hollow clothing to show solidarity. A blazer for Vivi. An emerald-green velvet dress for me. A brooch for our mother, despite her protests. A dash of Grey’s gag-worthy perfume at our wrists and throats, so we all stank of smoke and the dangerous part of the woods.

The dress was high-necked and rubbed against the scar at my throat, making it raw and itchy. I pulled the seam away from the scar, but it still felt like sandpaper working away at my skin.

The lead detective was standing, giving his opening remarks. “Miss Hollow does not have her cell phone with her,” he said. “We have not been able to track her through any social media. We are concerned for her safety. We are asking the public to be on the lookout for her, and for anyone who has any information regarding her whereabouts to come forward.”

The journalists were immediately feverish. “Do you think this disappearance is in any way linked to her disappearance as a child?” one of them asked.

“We don’t know,” the detective said. “We’re liaising with Scottish authorities to determine if there are similarities, though at this stage there doesn’t appear to be any correlation.”

“Where was her last confirmed location? Who was the last person she spoke to?”

“We can’t release that information yet. I’ll answer more questions in a moment. At this time, Miss Hollow’s family would like to make a brief statement.”

In another universe, I was in my Friday English class discussing Frankenstein with Mrs. Thistle. Instead, Vivi, Cate, and I were together at the front of an event room inside the Lanesborough. A crystal chandelier glinted overhead. The walls were richly paneled and gilt frame portraits lined the space; only the leopard print carpets felt modern.

My mother sat to one side of me, woody and brittle. Vivi sat to the other, slouched back with her arms folded. She stank, the oily smell of stale booze and sweat and cigarette smoke. Cate hadn’t been able to force her into a shower, so she’d sprayed her with extra perfume to mask two days of hard drinking. It didn’t help.

It was Grey’s agent who’d made the call to the police two days ago. We’d waited for them in her office, a chic, modern space adorned with framed pictures of our sister. They’d taken hours to arrive. There was no emergency, after all. No crime scene anymore, no body. Just a burned-down apartment and a missing girl—and girls went missing every day.

The police had arrived around sunset to take our statement. We had left out the details we couldn’t explain—the flowers growing on the dead man, the bull skull the man wore over his face—and told them only the bare-bones facts. Grey had left a note saying she was in danger. There had been a corpse in her apartment. A man had broken in and set the place on fire. He had shot Vivi.

The cops had been thorough yet workaday in their questioning. They had exchanged disbelieving, exasperated glances approximately every thirty seconds. I got it. Even with the craziest bits left out, it was a wild, implausible story from a wild, implausible family.

When the police left, Vivi called our mother, and the agent called Grey’s publicist. An hour later, the world knew that Grey Hollow—beautiful, strange Grey Hollow—was missing. Again. If Grey had been a famous supermodel a week ago, she was now something ten times more intoxicating: an unsolved mystery.

It was official. It had begun.

Which brought us to the press conference. The event had been planned for the dingy conference room of a local police station, but Grey’s publicist changed it to the Lanesborough.

We’d been instructed to look sad, demure, and helpless, which wasn’t hard. We were helpless. Grey had counted on us coming to look for her, and we had. Grey had squirreled away secrets that only we would find, and we had. Grey had left bread crumbs and bet on us saving her—and we had failed.

We’d missed something, some vital clue, and now Grey was really gone, and the only two people who might have a hope of finding her had screwed it up completely.

Something twisted in my heart at the thought of Grey alone somewhere, afraid, waiting for Vivi and me to rescue her. Waiting, and hoping, certain that we’d come—and eventually realizing that we wouldn’t.

I love you,I thought, gulping back a sob. Please know I love you. Please know I tried.

The journalists drank my moment of grief in hungrily. The flash of photographers left me headachy, disoriented. Cate stood and muttered her way through a plea for Grey to come home, her words never quite sounding convincing. Lips pursed, affect flat. I’d seen the footage of the press conference our parents gave the first time we went missing, in which our mother had verged on mania. Then her cheeks had been slick with tears, her eyes wide and red and wild, a wet tissue dabbed to her nose every ten seconds as she begged, begged, begged for us to be returned.

This was nothing like that.

It had been the hardest month of my parents’ lives. It had twisted and cracked them, both individually and as a couple.

They blamed each other. They blamed themselves. It had been Gabe who’d pushed to go to Scotland to visit his parents over Christmas and New Year’s. It had been Cate who’d wanted to take us walking through the streets of Old Town at midnight so we could see the fireworks and the revelry. It had been Gabe who’d decided the route. It had been both of them who’d taken their eyes off us to share a midnight kiss.

His fault.

Her fault.

Their fault.

Our fault.

Hadn’t they taught us not to speak to strangers? Hadn’t they taught us not to wander off? Hadn’t they been hard enough? Soft enough? Enough, enough, enough?

In the days that followed, our grandparents’ home was searched for blood, signs of a struggle. Cadaver dogs slunk through the halls and bedrooms, hunting for death. The gardens in the backyard were dug up, destroyed. Their car was seized as possible evidence. Dozens of witnesses were interviewed to try and piece together a picture of what had happened earlier in the day. Nearby lochs were dredged for our bodies. My parents took lie-detector tests. They were fingerprinted. They were photographed. They were followed, by police and journalists alike. The press took pictures of them at their worst moments. If they cried too hard, people accused them of faking it. If they tried to keep it together, people accused them of being cold.

God help them if they smiled.

No one believed their story—and why would they? It was impossible. Who could snatch three children without being seen, being heard? Who could do that in a matter of seconds? They couldn’t leave Edinburgh without an answer either way. They couldn’t work. They couldn’t stay at my grandparents’ house now that it was the scene of a suspected crime. They spent all their savings on hotels and rental cars and billboards with our faces on them. They barely ate. They barely slept. They knocked on every door in the Old Town. They drifted through the streets desiccated by despair, oily and fetid and thin. They oscillated between comforting each other and hating each other for what had happened.

Their souls—and their marriage—came apart at the seams.

They were perhaps only a couple of days away from being arrested for our murders when they made their pact.

“If they’re dead,” Cate said to my father, “do we kill ourselves?”

“Yes,” Gabe replied. “If they’re dead, we do.”

A woman found us on the street that night, naked and shaken but unharmed. The papers that had hounded my parents apologized for libeling them and paid big out-of-court settlements for damages—enough to enroll us all in a fancy private school.

Gabe and Cate had never recovered. They had been wounded too deeply, and wounded each other too deeply in turn. The worse in for better or for worse had been so much heavier than either of them could have imagined.

Now my mother was reliving that same tragedy. I squeezed her hand; she squeezed mine back.

Then our part in the press conference was over. It had been decided that Vivi and I wouldn’t speak, that we would take the focus off Grey, so as we all got up to leave the room, the whole press galley was shouting, asking the questions they’d been dying to ask from the moment they saw us.

“Iris, Vivi, is there anything you want to say about what happened to you as children?”

“Will you be assisting in the investigation?”

“What really happened to you in Scotland?”

“Do you think Grey has been taken by the same people who took you the first time?”

“Cate! Cate! What do you say to the people who still think you’re guilty of kidnapping your own children ten years ago?”

I kept my head down, eyes on the floor, my gut filled with oil. Police waved us into the next room, a quiet haven away from the vultures. After the doors had closed behind us, my family broke apart without another word. Vivi made a beeline for the hotel bar. I went home with Cate, back to our big, empty house. My mother shut herself up in her dark room, and I was left alone, still wearing my missing sister’s clothes.

My phone pinged in my pocket. It had been going off pretty much nonstop since the first press release, with messages from teachers and the parents of girls I tutored and fellow students who’d never actually spoken to me face-to-face but who’d gotten my number off a friend of a friend so they could pass along their thoughts and prayers.

This new message was from an unknown number:

OMG babe, so horrible about Grey!

Hope they find her soon!

P.S. Did you manage to pass my modeling portfolio to her agent? I linked it to you on Instagram, remember? I haven’t heard anything back yet. They’re probably busy with all this missing-persons stuff, but just thought I’d check!

I couldn’t stand to have the velvet itching against my skin anymore, cutting a hot path against my scar. I slipped out of it in the hall, then balled it up in my shaking hands and screamed into the fabric. I wanted to destroy something beautiful, so I took the dress and ripped. As I did, a curl of paper, delicate as filament, fluttered from some hidden place inside a seam. I sank to the floor, my back against the wall, and unfurled it. The note was handwritten in Grey’s signature green ink.

I’m a girl made of bread crumbs, lost alone in the woods. —GH

Yeah, Grey,I thought to myself. No shit.

What do you do when someone you love is missing? When all the looking you can do is done, what do you do in the long hours that linger ahead of you, heavy with absence and worry? Vivi’s answer was to get as drunk as possible for as long as possible, to disappear inside herself. My answer was to wander the floors of our house, dusting off memories of Grey in each room, Sasha trailing at my heels as though she could sense my grief and anxiety.

Here, in the cupboard under the stairs, was where Grey had layered the space with blankets and cushions and fairy lights, and read the Chronicles of Narnia to us every night for a year. Where I had pressed the pads of my fingertips into the plasticky bulbs of the lights as she read, and marveled at how the brightness shone through me, made fluorescent red by my blood, revealing capillaries and veins and all sorts of secrets beneath my skin.

Here, in the kitchen, was where she had cooked breakfast every Sunday morning, dancing around to the Smiths or the Pixies as she slammed through cupboards and left chalky storms of flour on the floor.

Here, in my bedroom, was where she had curled up next to me when I was sick and told me fairy stories about three brave sisters and the monsters they met in the dark.

Here, in her now-empty room, was where she had tacked the “Telltale Hand” palmistry guide poster above her bed and laden her shelves with salves and smudge sticks.

I sat on her bed for a long time, trying to remember what the room had looked like before she left. There had always been clothes scattered on the floor, and the bed was forever unmade. Tendrils of a wisteria vine had crept through her window and always seemed busy overtaking one corner of the room. A pink Himalayan salt lamp had sweated moisture onto her bedside table, curling the pages of her copy of A Practical Guide to the Runes, Grey’s favorite bedtime read. The dresser had been scattered with pouches of herbs, strings of crystals, and highlighted books on ancient Roman curse tablets.

All of it was gone now, and the girl was gone with them.

My mother was crying. It was not a new sound. It had been the backing track for much of my life. The house moaning in the wind and beneath it, my mother crying. I padded barefoot down the hall to her room, careful to avoid the creaky floorboard that would betray my presence. The door was open a crack; a slice of light jutted out. It was a tableau I recognized: Cate kneeling by her bed, the photograph of me and my sisters and my father in her hand. Her face was buried in her pillow as she sobbed, sobbed so hard I worried she would inhale fabric and feathers and choke.

In the afternoon, I sagged into my bed with my laptop and cycled between Twitter and Reddit and every news story I could find about Grey’s disappearance. It had exploded on social media. I followed hashtags and read deep into threads until my head ached with fullness, until my anxiety was a physical weight resting heavy inside my skull, until my body felt gouged out and desiccated. I picked my fingernails until they bled. I couldn’t breathe properly but I couldn’t stop reading and watching people’s reactions. Was it a publicity stunt or a hoax or a cry for attention or a misunderstanding or a murder or a suicide or a government conspiracy or aliens or a pact with the devil? I scrolled and clicked and consumed and filled myself and drained myself until I saw my mother pass my bedroom door around sunset, her scrubs on, her dark hair pulled back in her usual work bun.

I went to the hall and caught her at the bottom of the stairs. “You’re kidding me.”

“The world has to keep turning,” she said as she grabbed her car keys and made for the front door. The skin beneath her eyes was distended, her lips bee-stung.

“Why don’t you love her anymore?” I demanded, following her. “I mean, what could a seventeen-year-old girl have said to you that was so cruel it made you hate her?”

My mother stopped halfway out the door. I expected her to protest. I expected her to say I don’t hate Grey. I could never hate my own child. Instead, she said, “It would break my heart to tell you.”

I took a few deep breaths and tried to unravel what that meant. “Would you even care if she was dead?”

My mother swallowed. “No.”

I shook my head, horrified.

Cate came back to me then, pulled me into a hug, even as I feigned pushing her away. She was shaking, a frenetic energy humming though her. “I’m sorry,” she said to me. “I’m sorry. I know she’s your sister. I shouldn’t have said that.” I never felt more alien to Cate than when we were standing right next to each other, the height difference between us extreme. My small, sweet, blue-eyed mother, and then me, towering and angular. We were different species. “Don’t go anywhere tonight, okay? Please. Stay here. Stay inside. You know I can’t bear to lose you. I’m sorry . . . but I still have to go to work.”

And so she did. She left. I sunk onto the stairs, staring after her, a great twist of acid turning inside me. My scar was still itching from the velvet dress, so I dug my fingernails into it. There was a little hard nodule of scar tissue on one end now, inflamed by the rubbing fabric. I scratched it until it bled. The house felt too quiet, too filled with shadow and too many places for an intruder to hide. What if the masked man was already inside? What if he came during the night, while I was here on my own?

I checked Vivi’s location on my phone—she was still at the Lanesborough, still probably drinking at the bar. I hadn’t spoken to her all day. Vivi was volatile like that. She could be your best friend one moment, your coconspirator in all manner of mischief, then completely withdraw the next.

Another grim thought: Grey was the grounding force in our sisterhood, the sun we both orbited around. What would Vivi and I be without her? Would we drift apart in the cavernous space Grey left behind, rogue planets spun out into the abyss?

Would I lose both of my sisters at once?

When the doorbell rang, I thought it was Cate again, back to explain herself. I took my time getting to the door, opened it slowly.

“I need a drink,” Tyler Yang said as he pushed inside, walking straight past me without an invitation.

“Sure, come in, strange man I’ve only met once before,” I said after him, but Tyler had already found his way up the hall and into the kitchen. I heard cupboards banging, pots crashing. I closed the door and followed him inside.

“It’s above the fridge,” I said, my arms crossed as I watched him. He was more disheveled today, his black hair falling over his forehead, his skinny jeans ripped at the knees, but it worked. Even against the bland background of a suburban London kitchen, there was a swaggering, pirate-like energy to Tyler Yang, intensified by his smudged eyeliner, billowy floral shirt and leopard print House of Hollow trench coat that covered his tattooed arms. He was tall, lean. Inconveniently handsome.

He found the booze stash, picked the gin, and then took a long swig right from the bottle.

“Charming,” I said.

“Your sister is Gone Girl–ing me, I bloody know it,” Tyler said as he paced the kitchen, gin bottle still in hand.

“What are you talking about?”

“She’s faking it! I’m gonna go down for this and that’s exactly what she wants.” He took another long swig, then stopped, eyes darting from side to side in mad thought. “Does England have the death penalty?”

“Wait, you think Grey is faking her disappearance to . . . punish you?”

“Would you put it past her?”

I thought of how Justine Khan had shaved her head in front of the whole school. I thought of the male teacher Grey didn’t like, the one who kissed her in front of her class and got fired for it. I thought of how he’d insisted that he hadn’t wanted to do it, that she had whispered in his ear and made him. Grey Hollow did have a slightly warped sense of crime and punishment, and a way of making bad things happen to people who crossed her.

Tyler was pacing again. “A lot of strange shit happens around that woman. An unnatural amount of strange shit!”

I sighed. I knew.

“The police went to my flat while I was out, you know,” he continued. “Apparently, they have an arrest warrant.” He sniveled. “It’s trending on Twitter.”

I checked; it was.

“They’ve got something on you?” I asked.

Another muffled sob. Another swig of gin. “Hell if I know.”

“So you came . . . here? When the police are about to charge you with . . . what, my sister’s murder?”

Tyler pointed the gin bottle at me, his fingers dripping with thin silver rings. “You know I didn’t have anything to do with her disappearance. I can see it in your eyes. You know something, Little Hollow. Tell me.”

I shook my head. “We thought we knew something. We thought it might somehow be linked to what happened to us as kids, but . . . we’ve got nothing.”

“Fuck!” Tyler ran his hand through his hair, sweeping it back out of his face, then sank onto the kitchen floor, his head bobbed forward onto his chest and both arms limp at his sides. I went and crouched in front of him. Up close, I caught the stink of gin and weed and vomit, and wondered how drunk and high he already was when he got here.

“You knew her, Tyler,” I said.

He shook his droopy head. “I don’t know if anyone ever really knew her,” he said, his words slurred.

“Think. Think hard. Is there anything you can tell me, anything at all, that might be a good place to start? A name, a location, a story she told you?” I waited for a full minute, then shook his shoulder, but he flopped a hand in my direction with a whimper and then slumped back against the cupboard, unconscious.

“Oh, for God’s sake,” I said as I stood up.

Tyler was too heavy for me to move, so I found a spare blanket and pillow in the linen closet and left him there, sprawled out on my kitchen floor.

I woke on Saturday morning to the taste of blood and the smell of sweat and alcohol. There was a deep, jagged hunger inside me; I’d been chewing on my cheeks and tongue in my sleep. The blood was my own. It had dried on my lips, dripped onto the pillowcase. The smell of sweat and alcohol came from Vivi, still dressed in what she wore to the press conference yesterday, her makeup a cracking fresco on her skin. Her warm body was curled around me, one of her legs draped over my hip bones.

It had been a strange, sleepless night. The hours had clumped together and then fallen away in great chunks. I had only managed to close my eyes as sunrise blanched the winter sky. In the end, I had been grateful for Tyler Yang’s uninvited presence. Checking on him throughout the night to make sure he hadn’t choked on his own vomit gave me something to do that wasn’t worrying about Grey. The news of Tyler’s arrest warrant had spread fast and far on the internet, and I fell from one rabbit hole to the next reading about him, about his relationship with my sister and his career and his past. Which inevitably brought me to the tragic story of Rosie Yang.

I had been sitting on the kitchen floor next to Tyler when I came across the headline.

DROWNING HORROR:

WITNESSES TELL OF HAUNTING SCENES AS GIRL, 7, DIES ON FAMILY TRIP TO BEACH

I picked my fingernails while I read. It had happened years ago, when Tyler was five, at a busy seaside town in midsummer. There had been a heat wave. The beach had been packed with thousands of people escaping the sticky heat. Tyler and his older sister had wandered off from their parents and been found floating facedown in the surf not long after. Tyler was revived on the scene. Rosie could not be resuscitated and was pronounced dead at the hospital.

The article included a picture of her from her birthday party the week before. A little girl in a yellow sundress with the same black hair as Tyler’s, the same impish grin, the same dimples.

I had put my palm against Tyler’s chest as he slept and felt the steady rise and fall of his rib cage, the strong beat of his heart, and imagined the scene on the beach that day. The hands of a lifesaver against his chest, the compressions so deep they splintered his thin ribs. The bare, wet skin of his back pushed into the hot sand as onlookers crowded around, pressing their fingers to their mouths and holding their own children back so they couldn’t see. His parents hovering over him, hovering over his sister, barely able to breathe through the pain and the hope and the wanting. One child sputtering water from his lungs, a sudden intake of breath. The other limp, blue, cold.

Tyler Yang was confident and cocky and cavalier. Tyler Yang did not seem like a man with a tragic past. Yet the worst thing that I could imagine happening, the thing that was maybe happening to me right now—losing a sister—had happened to him already. He was a grim testament to a truth I knew but refused to acknowledge: that it was possible to suffer devastating, incomprehensible loss and continue to live, to breathe, to pump blood around your body and supply oxygen to your brain.

I sat in the kitchen for most of the night after that, checking Tyler’s breathing, Grey’s knife in my hand in case the horned man came back, until finally, at dawn, I crawled into my bed and collapsed.

I rested my cheek on Vivi’s tattooed chest and listened to the beat of her heart, one arm across her stomach. My heart beat in time with hers. The three of us, with the exact same rhythm in our chests. When one was scared, the hearts of the others knocked. If you cut us open and peeled back the skin, I was sure you’d find something strange: one organ shared, somehow, between three girls.

We were puzzle pieces, the three of us. I’d forgotten how good it felt to wake up next to her, curled into her, a whole with three parts. Grey’s absence felt raw and aching this morning. I wanted her more desperately than I ever had before. I wanted to find her and collapse into her and let her stroke my hair the way she had when I was little, until I fell asleep cocooned in her arms.

My sister. My refuge.

A tear slipped from the corner of my eye and hit Vivi’s warm skin.

She stirred when I started to sob. “Hey,” she said groggily, releasing a plume of sour breath. “What’s wrong?”

I nuzzled further into her. “I thought I’d lost you too. I thought you might not come home.”

“I’m not going anywhere.” Vivi shook her head against me. “I . . . I shouldn’t have left you here, Iris. After Grey ran away. I should have stayed here and watched out for you, helped you carry the load. I’m not leaving you again.”

Tyler burst into the room then, floral shirt crumpled, eyes wide, hair wild atop his head. “YULIA VASYLYK!” he said, pointing at me. “YES!” Then, as quickly as he’d appeared, he was gone again.

Vivi sat up and stared at the empty doorway, as if trying to make sense of what she’d seen. “Am I still wasted or did I actually just see Tyler Yang in your bedroom?”

“I think he’s hiding from the police,” I said.

“That’s . . . kind of genius. It’s the last place they’d look.”

Tyler appeared again and clapped for us to get up. “Little Hollows. That was a eureka moment. You must come.”

“I am way too hungover to deal with this,” Vivi said as we disentangled ourselves and went downstairs. We found Tyler in the kitchen, his bedding from the night before neatly folded on the bench. He was pacing again. I saw him differently now, this man who carried such tragedy in his heart. Sasha watched him from atop the refrigerator, her tail flicking furiously to show her distaste for this intrusion into her space.

“Yulia Vasylyk,” he said. “That’s where we start.”

“Are you speaking English?” Vivi asked as she sat at the breakfast bar and put her cheek on the kitchen counter, eyes closed.

“It’s a name,” Tyler said. “A woman. Someone Grey has mentioned before.”

I was so hungry, my stomach felt like a black hole expanding up into my rib cage. I pulled out my phone, typed Yulia Vasylyk into Google, and hit return.

The disappearance of Yulia Vasylyk three and a half years ago had not been big news. There were only a handful of short articles, and two of them had referred to her as Julia.

“I don’t get the link,” I said. “Another missing woman?”

“Type Yulia Vasylyk Grey Hollow,” Tyler said.

I was skeptical but did what he said. Google returned only one exact match. I read it out loud.

UKRAINIAN WOMAN FOUND A WEEK AFTER BEING REPORTED MISSING

Nineteen-year-old Yulia Vasylyk, an aspiring fashion model from Ukraine, has been located one week after her boyfriend reported her missing. Vasylyk was found wandering near her Hackney apartment late Monday night, barefoot and confused. Police took her to a nearby hospital for evaluation. No further details were released.

In a strange twist of fate, Vasylyk shares hçer small, one-bedroom Hackney apartment with three other girls, among them . . .

I stopped reading and looked up at Tyler.

“Keep going,” he urged.

I took a breath and continued.

. . . among them another famous missing-then-returned person: Grey Hollow. Hollow, now eighteen, was abducted from a street in Scotland when she was a child, but found safe one month later.

Neither Vasylyk nor Hollow could be reached for comment.

“Holy shit,” Vivi said, lifting her head from the kitchen bench. “It happened again.”

Tyler was grinning. “Bingo, baby,” he said, snapping his fingers. “Someone else came back.”

Fullepub

Fullepub