7. Cricket

From her table at the far end of the dining hall, Cricket watched the campers with a mounting sense of awe. Her cousin had written about the camp, and for years, Cricket had read descriptions of human and inhuman kids sitting together, laughing together. Forming friendships and romantic involvements. But to see it firsthand was something stellar indeed. Where else could a naga and a gnome share a piece of cake? Where else could she watch a teen girl teaching a skunk ape how to twirl spaghetti with his fork?

Gods, she wished her parents were here to see what she did: a future, hope, a world outside of Green Bank and its ever-shrinking forest.

A plastic tray slapped against the table, and a figure slid into the seat opposite Cricket, obscuring her view of the campers. She blinked, gaze refocusing on the pale, freckled face and frizzy red hair of Avery.

She offered a tight-lipped smile as she settled, placing her hands in her lap and bowing her head.

“What are you doing here?”

Avery snapped her head up. “Eating?”

“Yeah, no duh. I mean here.” Cricket waved her fork over the table, where she’d been perfectly happy sitting alone. “Don’t you have campers to sit with?”

“That’s not … that’s not really how it works.” She raised her hands from her lap and straightened her fork. “I’m the Assistant Director. I’m not in charge of a singular cabin; it’s my job to make sure the campers are comfortable and having a nice time, dinner included.”

Cricket stabbed the bowl of sprouts, grains, and roasted vegetables Nurse Almaden had put together for her at the buffet. “I’m not one of your campers.” She pointed the bite at Avery before shoving it in her mouth.

“No, but you’re in the camp, and you’re eating our food, so for all intents and purposes, you’re one of us.”

“Right.” She shoved another forkful into her mouth, chewing loudly before asking, “Did you get your filing done?”

Avery, who had bowed her head again, peered at Cricket beneath thick lashes. For the briefest instant, she thought she tracked annoyance in her expression, and then the girl dropped her gaze away, mumbling something unintelligible.

“What was that?”

“I said, ‘no’,” Avery snapped. “I didn’t.”

“I thought you had to submit an insurance claim.”

“I did. I do, but I …” She glanced side to side, cheeks flushing a sweet shade of pink.

Cricket set her fork down and laced fingers under her chin, lips curling in amusement. “Oh, this is gonna be good.”

“I don’t know what you are,” Avery squeaked. The pink blazed hot, cherry tomato red. “The form asks what species you are, and I don’t … I’m not …”

“Woooooow.” Gripping the edge of the table, Cricket leaned back, drawing out the moment with feigned shock. Of course, the human wouldn’t know what she was. As far as Cricket knew, no one did. The faun, at least, her family unit, had dropped through the veil fifteen years ago and remained hidden.

Not even the people of Green Bank spread the word of their fae friends in the forest. The faun kept the predators away, planted produce, and tended the earth, and the people of Green Bank bought their vegetables and thanked them for the lawn care. Being an isolated town smack dab in the middle of a radio-free zone, the people were almost as technologically adverse as the faun. Just like the song said, their little patch of West Virginia was almost heaven. Until recently.

But apparently, Avery had no idea the faun were unheard of, and the opportunity to watch that lovely blush color her cheeks was too good to pass up.

“You’re the Assistant Director of an integrated camp, and you can’t tell one inhuman from another?” Cricket clicked her tongue, ears twitching underneath her curls. “What, do we all look alike to you?”

“No!” Her eyes bugged, and her lips formed a plush, lovely circle. “Oh my goodness, not at all.”

“Oak and ivy, your face.” Cricket pealed with laughter, wrapping arms around her stomach as the human turned deeper and deeper scarlet. She didn’t even care that her laughter came out in short, bleating bursts. “I’m totally messing with you.”

She grinned at the human, tears limning her eyes from the laughter, and then froze at the new look on Avery’s face. Her eyes were wide but reddened and sheened, her brow wrinkled and lower lip trembling. In that look, Cricket knew she’d gone too far, teasing someone who took herself far too seriously.

“Hey,” she said in a low voice, reaching across the table. Without giving thought to the gesture, she pressed two metal-capped fingers lightly against Avery’s hand. She stared down at the touch and then jerked her arm away as if she’d been burned. Cricket kept still, taking the insult in stride. “I’m sorry, I didn’t think—”

“No, it’s my fault,” Avery whispered and transformed before her very eyes. She sat up straight, rolling those soft shoulders back and raising her chin. In a blink, her eyes were dry, if still red. She gave a curt nod and plucked her napkin from the tray as Cricket shoved a forkful of food into her mouth, chewing in silence until Avery asked with all the poise of a hostess, “What brings you to Elkwater Music Camp?”

Cricket, hunched over her meal with both elbows on the table, looked up from her vegan bowl. She finished chewing, swallowed, and blew a curl out of her eyes. “Came for help.”

Avery’s cold expression eased, and she leaned slightly forward. “Help?”

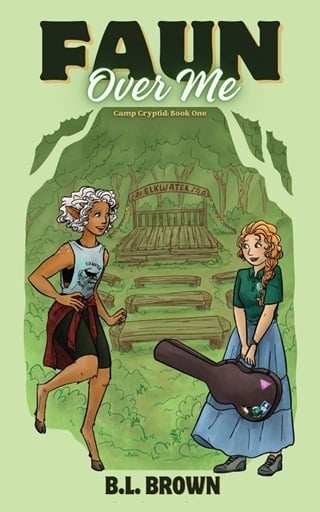

“Someone keeps buying up the land where we live—faun, by the way.”

She blinked.

“Kind of related to satyr, but also, like, deer?” Did Cricket imagine it, or had Avery’s shoulders relaxed as well? “So, add that to your form.”

“They want to push you out?”

It was Cricket’s turn to blink, taken aback by her sudden interest and the hint of concern in her voice.

“I-I don’t know,” she admitted. “That’s what it feels like. Every time we settle in a new part of the woods, the land gets bought, and we get pushed out. Used to be we could spread out, but now the dens are getting closer and closer.”

“Why don’t you move?”

Cricket huffed a laugh, shaking her head. “I wish it were that easy.” She poked the food in her bowl. Gods, why was she even telling Avery all of this? She didn’t even know what faun were and was clearly out of her depth in dealing with inhumans. But there was something about how she leaned forward, completely engaged in Cricket’s story in a way no one in her family had been for years.

She knew why; it wasn’t hard to figure out. They were tired of her pestering the family to move. Tired of her wild claims and cries of evil real estate developers. Tired of her criticisms. When she was younger, her mother and father would humor her, nodding and smiling and placating her with repetitions of “one day,” and “wouldn’t that be nice,” and “you will understand why we stay when you are older.”

When her cousin married, Cricket was hopeful they would see how integration was possible beyond Green Bank. See how the faun could have more than their ever-shrinking patch of woods, but the elder faun, like her father, Bosk, were immovable, and Cricket was desperate.

“It’s complicated,” she said, those two words failing to sum up the last decade of her life. “Anyway, I came here to find my cousin; they’ve lived at the camp full-time for the last eight years.”

“There’s no one here like you.”

The words were spoken quietly, almost reverently. Cricket snapped her gaze to Avery, who was prodding the food on her plate, cheeks once again flushing the lovely pink of a mountain laurel in late spring.

“I … thanks?”

“I mean, I’ve never seen another, um, faun. We have naga, wolven, gnomes, and all sorts of campers in the Sasquatch family, a few lizard people. There’s a satyr around here somewhere; he’s in the woodwinds, but I haven’t seen another faun.”

“They’re here,” Cricket stated. “Just got stuck out of town with the road closures.”

“Oh, those should be cleared in the next day or so.” Avery twirled her fork in the air. “Still, I’ve never seen another faun in the camp.”

“How do you know?”

“I’m the Assistant Director.” She raised an eyebrow, blue eyes intent on Cricket. “It’s my job.”

“No,” she shook her head. A half smile quirked her mouth, and, to her surprise. Avery’s delightful blush returned. “How do you know the roads are re-opening?”

“My dad has a meeting in Green Bank, over the ridge. Some business deal. He wouldn’t make the drive from Harrisburg if he thought he couldn’t get to the real estate his client wants him to inspect.”

Cricket stiffened at the name of her small town. Her ears pressed flat against the side of her head as a new suspicion about Avery, or rather, her family, arose. “What does your dad do?”

“He’s a lobbyist.” She set her fork down at a perfect ninety-degree angle, then straightened her already straight tray. “His firm has worked with US Petrol forever. They’ve been pushing for a new pipeline.” Avery folded her napkin into a perfect rectangle and ran a finger along her knife and spoon, ensuring they were parallel to her plate. Cricket wiped her mouth with the back of her hand, watching the performance with interest. “Before I came up here, my dad was pretty deep into the project; they’re purchasing the land on behalf of US Petrol using a third-party firm in Atlanta.”

“Atlanta?” Cricket’s ears perked up, and Avery’s gaze lifted, dancing from one side of Cricket’s face to the other. “Like, in Georgia?”

“Where else?”

At Cricket’s lack of response, Avery again lowered her head, hands disappearing under the table. She exhaled, shoulders dropping, and Cricket’s ears pricked forward at the sound of low mumbling. She ducked to the side and caught sight of Avery’s lips moving. It was hypnotic how the plush pads formed each silent word. Her gaze drifted over Avery’s face, lingering on her eyelashes, long and curled in a delicate arc so much darker than her hair and skin, the contrast beautiful and alluring.

That thought straightened her back. Unsure of what to do, she grabbed her glass and swallowed the last of her water before asking, “What are you doing?”

“Praying.”

“Why?”

Avery cracked open one eye, peering up at Cricket. “Because it’s what you do.”

She glanced around the dining hall at the other counselors and the campers. Chatting, eating, laughing. “No one else is doing it.”

Her head jerked up, neck crawling red. She flipped her hand at the dining hall at her back. “No, they aren’t, okay? They think it’s weird, too.”

Cricket glanced around their table, shoved in the furthest corner of the room and curiously empty when she’d taken her seat only moments before Avery joined her. Her stomach dropped, and she took in the human girl with fresh eyes.

“I didn’t say it was weird,” she said. “I just asked what you were doing.”

“You … don’t think it’s weird I pray before my meal?”

She gave the question a beat, feigning thinking about it before responding, “I mean, I didn’t say it wasn’t.”

Avery’s chin tucked, her head tremoring in tiny surprise, and then she unleashed a peal of giggles that rang like a bell. “I knew it! You do think I’m weird.”

“Yeah, well, tomato, lycopersicum.”

Campers streamed past, chatting and laughing, some holding hands and scurrying into the dark. The sun had set since she entered the dining hall, and now, in the dark and alone, Cricket had no idea where to go. She leaned on her new crutch as she scanned the crowd for a counselor or Nurse Almaden and found neither.

“Need help?” Avery skipped down the stairs, skirt flouncing around her ankles and twisting between her legs. She scowled, tugging the fabric free and tossing it aside with a huff.

“Do you?”

“What?” Avery’s eyes widened. Lights strung along the central path of the camp reflected in the blue, bringing to mind planets gleaming in a spring dusk sky. “Oh, no. It’s just the skirt; it gets in the way.”

“Then why do you wear it?”

“You are full of questions tonight, aren’t you?” Avery smiled as she walked by, stopping after a few paces to call back. “Are you coming?”

“Depends. Where are you going?”

“Shortcut to the Director’s Cabin.” She pointed at a trail running along the side of the dining hall. “It’s about a ten-minute walk if you take the main trail, but if we shortcut behind the field, it’s closer to five.”

Cricket flexed her hoof, swallowing a wince as a sharp pang warbled up her shin. “Okay then.” She followed Avery around the building and out onto a large grassy field. In the low light bleeding from cabins and the dining hall, she could make out bleachers and light poles black against the sky. Avery kept close to the low-lying building running the length of the bleachers, walking at a hurried pace that Cricket struggled to match.

“Hey, slow down.”

“What?” The human glanced over her shoulder, slowed, and then stopped, waiting for Cricket to catch up. “Sorry, I didn’t want to bother anyone.”

“Bother who?” She glanced around, ears pricking at the quiet. The purposeful quiet. She peered under the bleachers, picking out shadows that were deeper than they ought to be. Avery cleared her throat, the sound coming from much closer than Cricket anticipated. Less than a hand-span away, Cricket could feel the girl warming as if she were blushing from head to toe, the heat of her embarrassment radiating off of her in waves.

Her ears pricked, shooting upright from her curls and swiveling toward the sound of a low moan coming from the shadows. Realization struck, and she laughed. “Oh, my Gods.”

“Ssh!” Avery grabbed her wrist lightly, tugging Cricket into movement.

Her grip was strong, not soft like she would have guessed from Avery’s appearance and demeanor. But then again, she was a musician. Cricket only played panflute, but a few members of her family had branched out to other human instruments. Guitar and banjo were the most popular—their extra knuckled fingers lent the faun an advantage, and the hours of practice strengthened their hands. The lack of fingernails was a bit of a hurdle at first. To get around it, the faun who had picked up those instruments wore metal caps on the tips of their fingers, the ends hammered to a nail-like point, and the necessity had become a fad among Cricket’s generation.

“It’s a shortcut, I promise,” Avery muttered over her shoulder.

“And a well-known one at that.” Cricket snickered, craning her neck around to spy on the lovers under the bleachers. “How many are down there?”

She thought she heard Avery grumble, “I don’t know,” but whatever she said was lost as she cut between two buildings. The narrow width of the breezeway forced them to walk single file. Avery dropped Cricket’s wrist, and she adjusted herself to face forward rather than hobble at an angle. The wood panels of the buildings brushed her shoulders on either side, and she shuddered.

“It’s really tight.”

“Claustrophobic?” Avery asked.

“Yes.”

“I’m sorry.” Avery looked over her shoulder. “I didn’t know.”

“It’s alri—”

Avery stopped abruptly, spitting and swiping at her face with both hands. Cricket bumped into her, something wispy tickled her ears, and Avery screamed. Every hair rose along Cricket’s neck and shoulders, the sensation of that scream like that of metal tips scaling down the strings on a guitar. Avery darted down the breezeway, spinning in a circle once she had the space to do so. Her hands flew down her front, batting at her skirt, then returning to her face as she chanted, “Ew. Ew. Ew.”

Cricket hobbled out of the breezeway and into a small backyard. A soft yellow glow spilled onto the lawn from the light on a wrap-around porch, illuminating a small grill, two lounge chairs, and a picket fence. Flowers she recognized from growing up in Green Bank hugged the fence, and in the far corner of the yard, beneath a Mountain Ash already blooming with berries, was a hammock and a soft, welcoming bed of pine straw, grass, and all-weather pillows.

A small breeze wafted through the yard, tickling across the back of Cricket’s neck.

Wait.

Was it the wind or a …

“Oh, Gods.” She copied Avery’s awkward dance, dragging spiderweb away from the back of her neck and out of her hair. A swipe at her throat brought away something with structure, and Cricket shot her hand out, whimpering at the sight of an orb-weaver spider scurrying up her arm.

“Oh, gosh, are there more?” Avery shrieked and pulled at her hair, loosening the long, frizzy ponytail. A cascade of fire poured down her back, tiny curls crowning her brow as she shoved her hands into the mass and shook it out. Cricket stood transfixed by all of that hair. Porchlight danced in the strands, illuminating golds and oranges. Just as quickly, it was whisked away, pulled into a messy bun on top of Avery’s head. “I swear that web wasn’t there yesterday.”

“You have beautiful hair,” Cricket replied. Avery stared at her, eyes wide, lips parted. Oh, Gods. Cricket scrunched her eyes, pinching the bridge of her nose. “I mean, I believe you.”

She opened her eyes to find Avery staring at her, lips now pursed as if she were about to speak. Instead, she coughed into her fist and faced the stairs. “This way.”

The back porch was cluttered in the way of frequent use. A basket of shoes sat by the door, and two rocking chairs flanked a small wood-burning stove and a metal barrel of logs. Flannel blankets covered a wicker loveseat, and she caught the undeniable scent of her cousin woven in with the fibers.

Avery tested the knob on the backdoor, nodding when it proved to be unlocked and facing Cricket. Again, she noticed the human’s height—the perfect height for Avery to rest her head on Cricket’s shoulder.

Her ears twitched, and she tucked her chin.

Where in the hells did that come from?

The gentle brush of Avery’s fingers startled her from the thought. They plucked at her sleeve and the soft down on her shoulder before lifting away, flicking something from the tips. “You’ve got some …” Avery looked up, brows bunching together as her eyes darted over Cricket’s face, her hair, like the faun was a puzzle she couldn’t figure out.

Her tongue darted out, moistening her lower lip and drawing every iota of Cricket’s attention to her mouth.

Oh. Oh no.

She knew herself well enough. Had known for years where her interest lay, and it always started like this: noticing the little things like the strands of gold woven into fox-fur hair and how that tiny line appeared when Avery was considering something.

I need to go inside. I need to get away from her. This is a terrible idea. She doesn’t even like me. I’m not even sure she likes girls or females or …

Her hooves wouldn’t move, and Avery’s eyes were impossibly large in the low light, her upturned nose giving her a fae, otherworldly appearance, like one of the fair folk from her mother’s books but far shorter and with more curves and—oh, Gods.

“You have something …” Avery reached up. The movement startled Cricket enough that her instincts took over. Rooted in place, eyes pinned on Avery, her ears shot straight, intent on every sound on the porch and in the woods beyond. Trapped by the glowing reflection of the porchlight in Avery’s eyes. “Here.”

Her fingers lightly brushed the tip of an ear, and a thrill of pleasure shot straight down Cricket’s spine. She bit her lip, barely halting the whimper that a single touch elicited.

She wouldn’t know. She couldn’t know. She said there’s no one here like me, and she’s clearly never been around inhumans before this summer. There’s no way she could know.

Still, she screwed her eyes closed, forcing slow breaths through her nose as Avery’s fingers continued their soft, teasing touch. Gods, the light pinches were beyond teasing. This was torture.

Her nipples pebbled all the way down her torso, and she thanked the Gods she’d worn a shirt that covered her body, even as a low, heated throb began in her core.

Avery’s fingers scaled the inner curve of Cricket’s ear, and a sound rose in her throat. She darted her hand up, grabbing the human’s wrist. “Please,” she managed. “Please stop.”

“I’m sorry. I—” Muscles flexed beneath Cricket’s palm, and she let go, finally zeroing in on what Avery held pinched in her fingers. “Spiderweb.” She smiled sheepishly. “It was caught in your hair and your ears.”

“Yeah.” Cricket swallowed, body burning from the echo of that soft, teasing touch. “Yeah, I need to go.”

She rushed inside, leaving Avery in all that soft, invitingly low light, and let the door slam behind her.

Fullepub

Fullepub