6. Avery

“You were where?” Nurse Almaden’s beady eyes widened. She blinked, and then twitched her head to the side in a very birdlike manner, assessing the pair.

“The woods,” Cricket muttered. She gripped the edge of the counter and slid her arm off of Avery’s shoulders. Soft, downy fur tickled the base of her neck, and she shivered, hugging her arms around herself. “I went for a walk.”

“You split your hoof!”

“That happens all the time.”

“And sprained your ankle,” Almaden squawked.

Cricket shrugged and made a soft sound that sounded like “meh.” She hobbled to the chair and collapsed into the cracked, worn leather. Dropping her head back with a relieved sigh, she stretched her arms and groaned in a way that had Avery spinning to stare out the window.

Classes and practice were done for the day, and campers wandered through the middle of camp, laughing with their friends and fiddling with instruments as they made their way to the cabins. In the hour before dinner, Avery usually headed to the practice rooms and lost herself in music, dancing her fingers over a keyboard or chasing a melody on her guitar, working out all the tension of her day in a melodic world of her own. Any filing or scheduling she needed to do for Director Murray could wait until after lights out when the camp was quiet and the night calm, but she found herself antsy to complete something. Anything. To achieve something instead of wandering aimlessly in the chords of an unnamed song.

“Sss, ow.” Cricket hissed behind her, that raspy, rusty voice sizzling in Avery’s ears.

“Apologies,” Almaden muttered. “But you did this to yourself.”

“I was bored.”

“Your cousin gets bored, but I never see them being stupid about it,” the nurse clapped back.

Cricket muttered something Avery couldn’t catch, and she twitched her face to the side, catching the inhuman from the corner of her eye. Nurse Almaden perched on a stool in front of Cricket and was unwrapping the filthy ACE bandage from her ankle. She’d pulled a rolling service tray up beside them, the surface loaded down with antiseptic spray, gauze, gels, and a fresh bandage.

Cricket’s leg stretched between them, the nurse careful not to pinch her calf with the neatly filed points of her short talons. Her upper lip was curled back, blunt teeth clenched together. She gripped the armrests, the tips of her fingers bent slightly backward. Sunlight glinted off of the metal caps she wore on half of her fingers—three on her right hand, covering her thumb, index, and middle fingers, and two on her left, capping her index and middle finger.Avery turned all the way around, puzzling the purpose of the caps.

“No nails,” Cricket gasped. She hitched in the seat, shoulders rising as the nurse sprayed antiseptic on her hoof. Avery flicked her gaze up to the inhuman’s, heat burning her cheeks as she realized she’d been caught staring. Cricket waggled the fingers of one hand as Almaden prodded her hoof with a Q-tip. She hissed, eyes clenched in pain, arching her back in the chair. Her head fell back, and Avery’s gaze was drawn to the long line of her throat. She coughed lightly into her fist and aimed for the door. “I should go start the paperwork.”

“No need,” Nurse Almaden called out.

“No need?” Avery whirled around. “Cricket was hurt on camp property; I need to file a report.”

“That’s not necessary.” The nurse didn’t bother looking up from her task. She poured a measure of hydrogen peroxide on the hoof, and Cricket grunted as white foam rose, squirming but managing to remain in the chair.

“What if she sues?” Avery gestured at Cricket, who cracked open one eye.

“I live in the woods; how would I retain an attorney?”

“Okay, so you know you’d need to retain an attorney, which suggests a certain amount of risk.”

Cricket snorted, and twin patches of blonde curls on either side of her head danced. “I’m not going to sue the camp, but I do need to talk to ‘Director Murray.’” She crooked an over-long finger on each hand, palms still flat against the armrests, as she said the director’s name. “Need to tell her about what chased me.”

“Why don’t you fetch the director, Avery,” Almaden said, beady eyes intent on Cricket’s hoof. “I’m sure she’ll echo what I’ve said.”

Avery left without a word, jogging down the stairs and charging across the center promenade toward the director’s cabin. The lights were off inside, save for the small lamp on a table beside the door. The light Director Murray always left on.

“To keep my wife from tripping,” she’d explained. “They’re an early riser.”

Turning on lights as she went, Avery headed to the office where the filing cabinet with the insurance forms lived. Despite Nurse Almaden’s instruction, she had every intent of filling out the appropriate forms and maintaining a record of events. Just in case, she told herself.

Settling at the desk, she glanced over the form, hesitating with a pen poised over the line asking for Species.

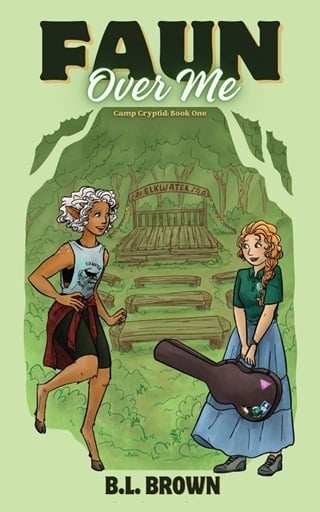

What was Cricket? Avery had never seen an inhuman like her. Granted, she’d never seen half of the inhumans at Elkwater Music Camp before starting this job, but still—what had long graceful legs and cloven hoofs. A satyr? Were those even real? Inhumans had only come around in the last fifteen years; the news reports of the sudden influx of mythological and fae creatures were some of Avery’s oldest memories, but satyr had been depicted in ancient art. Had inhumans always been here, only just now deciding to come forward?

And if so, why?

She scanned the desk as ifDirector Murray’s papers held the answer. Grocery and supply lists submitted by the dining hall and counselors were strewn across the surface, along with bills, marketing proofs, and a blueprint for the proposed renovation and expansion of the camp. Additional bunks, a second marching field, an acoustic dome for the amphitheater, a theatre complex, and a chorus room—all the dreams Director Murray had for the camp that would never be realized if she failed to find investors and sponsors.

Avery set the blueprints aside and frowned at the yellow notepad with her name scrawled at the top.

She snagged the notepad, deflating in the chair with a sigh as she read the message:

“Avery – your dad called. Call his office. –M”

She sighed again, setting the paper down and pinching between her eyes. There was no time listed to tell her when her dad had called, but knowing Nathan Payne, he’d be in his office for another few hours until her mom had finished putting the youngest kids to sleep.

Steeling herself, Avery pulled the phone closer and dialed his work number, silently praying for the line to keep ringing and clenching her jaw when her father’s secretary answered.

“Payne Strategies,” Mrs. Jones greeted, her voice crisp yet kind. “How may I direct your call?”

“Hi, Mrs. Jones. Is my dad available?”

“Eliz—Avery!” She corrected herself, the formal tone giving way to what sounded like a smile. “Hey honey, how are you? How is summer camp?”

“It’s good. Busy, but good.”

“They feeding you enough?”

Avery laughed, her apprehension put at ease by the middle-aged woman’s care. Mrs. Jones had worked for her dad for close to a decade and for the lobbying firm her dad had inherited for a decade before that. Her cheerful, kindly nature hid a cunning secretary with a steel-trap of a memory that had put no small amount of politicians in their place. “Almost too much, but nothing’s as good as your tater tot casserole.”

“And that is how you get yourself a care package of cookies,” Mrs. Jones said. “You calling for your father, honey?”

“I am, had a message that he called the camp earlier.”

“Got it; he’s just finished with a meeting. Let me patch you through.”

“Thanks, Mrs. Jones,” Avery said. “It was nice to chat with you.”

“You too, Avery. One sec.”

The line went silent, long enough for Avery to take a deep breath and center herself in a place of calm before her father picked up.

“Elizabeth! How’s my eldest daughter?” Nathan Payne’s voice boomed as loud and forceful on the phone as he was in person. Avery drew in a quick breath, tensing at the sound even though miles separated them. His office was in the heart of Harrisburg, and Avery was safely tucked far and away in the Appalachians. He wasn’t here; he wasn’t anywhere near her, and yet the crushing weight of her father’s personality had Avery wanting to shrink against the wall to avoid his notice.

“Good, Dad. You called?”

“Right to the point, that’s my girl,” he chuckled. “I was beginning to think you weren’t going to call me back. Doesn’t your last class end at three?”

“There was an issue with a camper,” Avery mumbled. “I had to take her to the infirmary.”

“Is that what they have you doing up there? Babysitting monsters and applying Band-Aids?”

“No, Dad, it—” Avery exhaled, dreading the coming argument. “I’m the Assistant Director, it’s my responsibility to—”

“You told your mother and I that this was a stepping stone, Elizabeth. A strategic choice to further your career, not an Inhumanitarian Aid Mission.”

“It is, Dad. I mean, it isn’t—”

“You need to keep your focus, Elizabeth,” he stated, launching into the tirade Avery had heard numerous times throughout the weeks leading up to the day she left for Elkwater Music Camp. “Carnegie Mellon isn’t going to want someone who gets easily distracted. They want students in their program who are focused. No matter how many musicians Murray has churned out over the years, you’re still just a girl. Integration has only made it harder for humans to succeed. Affirmative Action, my ass.”

“Dad!”

“It’s an overreaction from bleeding-heart liberals thinking equality means leaving our children behind.”

Avery closed her eyes, inhaling through her teeth. “Was there something you wanted to talk about, Dad? The dinner bell is going to ring any minute.”

“Wouldn’t want to keep the monsters waiting.” He chuckled as if it were a joke and not how he actually thought and felt about inhumans. Avery pressed her lips together. “So much like your mother. Listen, kiddo, I’ve got to run, but I wanted to let you know I’ll be in the area later this week.”

Avery’s eyes flew open at that, dread curling in the pit of her stomach. “Why?”

“Meeting with a business partner up from Atlanta. US Petrol has an interest in the Monongahela; you know how it is. Got to get to Green Bank and put eyes on the property. Thought I’d swing by and take my little girl out to lunch. Mix a little pleasure with business. Think you can step away from babysitting the monsters for an afternoon with your old Dad?”

“I mean…”

Avery fumbled for an excuse not to see him. She might be struggling to fit in at Elkwater, fighting every day against lifelong lessons and biases, but the camp was still a respite. An escape from her father’s views and loud opinions. She would have to return home at the end of the summer, living back under her father’s roof until it was time to move to Pittsburgh. Avery refused to think about what would happen if Carnegie did not accept her. She didn’t want to think about the pressure he would place on her to marry a Penn State boy and pop out more little Paynes. Her time at Elkwater may be fleeting, but it did not make it any less of a haven.

A haven she didn’t want poisoned by his presence.

“Um, I think the roads are still closed. There was a storm that—”

“They’ll be cleared by tomorrow. Given the amount of money my client is throwing at the towns up there, I’m surprised they’re not already cleared for their trucks. Day after next, Elizabeth. My associate and I will pick you up.”

The line went dead, and Avery stared at the desk, eyes burning. Road closures or not, there was no way her dad wouldn’t follow through on a promise to US Petrol. They’d engaged Payne Strategies when her grandfather was still in charge, and the firm had built its reputation on that relationship, lobbying for pipeline expansions and barrel rates for the last fifty years.

She exhaled and pressed the tips of her fingers against her hairline. She knew it was too good to be true. Knew her parents would never let her have this summer for free. There was always a cost with Nathan Payne. Always a hoop to jump through and a dance to perform. That he was meeting a business associate told Avery everything she needed to know: her role wasn’t to enjoy lunch with her dad. It was to smile and be silent, the perfect Christian daughter upholding the image of fine, upstanding American values that Nathan Payne had launched his career on. God and country. A Family man. Human.

The dinner bell rang, and she jumped from the chair, tearing Director Murray’s note from the yellow pad and crumpling it in her hand. Her skirt tangled in the legs of the chair, and she gave it one strong tug, clenching the fabric in her fist.

What was done was done. Her mother always said that whenever a decision was made that Avery and her siblings disagreed with. Whether it be the location of the family vacation or the toppings on their pizza, what was done was done, and there was no use wallowing in it.

“Lift your chin, bite your tongue, and act with grace.”

Nathan Payne was coming to the camp. Avery could suffer one lunch. She could act with grace for a meal, and then he would be gone.

Easy.

Fullepub

Fullepub