Chapter 8

"She must have been makinga list of everything she knew about the baby's father," I said. Unnecessarily, since none of us were stupid and the other two had surely figured that out for themselves already. "I guess we can assume that they met at the Hammersmith Palais de Danse."

"In April of last year," Christopher nodded, "judging from little Bess's birthdate."

"And he had fair hair and blue eyes and drove a black motorcar," Constance added.

"They must have left together, for her to have seen the vehicle."

"He probably took her back to wherever she lives," Christopher said. "Or where she lived at the time. It's a shame she doesn't know a bit more about motors. She might have noticed a make instead of just a color."

I nodded, looking from Uncle Herbert's black Bentley to Uncle Harold's black Crossley. Every man in the family had access to a black motorcar in April of last year, so knowing that the vehicle had been black was remarkably unhelpful.

"At least Crispin's car is blue," Christopher said.

I shook my head. "He still had the Ballot last spring. He didn't destroy it until autumn. And anyway, he had access to his grandfather's car, I'm sure."

Christopher snorted. "Have you lost your mind, Pippa? Do you really suppose Grandfather—or for that matter Wilkins—would have allowed Crispin to drive Grandfather's precious Crossley? Besides, why would he have needed it, if he had a motorcar of his own?"

He wouldn't have, of course. Unless it had been during that period when the Ballot was out of commission, before he had replaced it with the Hispano-Suiza. But that had been nine or ten months ago, not last spring. "At least the blue eyes take him out."

"Not necessarily," Christopher said. "In that kind of setting, and in the dark, gray can look very much like blue. I'm not sure we can eliminate anyone based on the eyes or the car."

"Well, you all have fair hair," I said, "so that's hardly helpful. You're all grandsons of the Duke of Sutherland. Or were, back then. Now, nobody is the grandson of the Duke of Sutherland."

There was a moment's silence.

"I hate this," I said. Constance nodded fervently.

"At least Mum will have nappies for the baby." Christopher began shoving everything back into the tote again, only to stop, guiltily, when there was a scuff of a foot nearby.

We all looked up, and I daresay we looked very much like we had something to hide. But it was only Wilkins, back outside the carriage house again. He had a cigarette in one hand and a lighter in the other, and he had probably expected us to be long gone, because he looked from us to the tote and the stack of folded nappies Christopher was busily shoving back inside with consternation.

"We found the girl's bag," I said brightly. "We thought we'd… um… take a look inside before we brought it to Aunt Roz and Uncle Herbert."

Wilkins didn't say anything, and I'm sure I sounded very much like a fool, trying to explain myself to the chauffeur. And not even my own chauffeur, but Uncle Harold's.

"Never mind," I added. "Carry on, Wilkins."

"Yes, Miss Darling." He gave the bag one last look before he walked in the other direction. Away from the house and the cars, towards the hedgerow screening the property from the road, where he could suck on his gasper in peace.

"Done," Christopher said. "Come on, Pippa. Let's get this to Mum before the baby needs a change."

He handed the bag to Constance, who looked dubious but took it.

"Coming," I said, with a last look at Wilkins. "How much did he take you for, anyway?"

"Who?" Christopher glanced at him, too. "Oh, just a few shillings. Not much."

He shook his head. "It must be terribly boring, just waiting around for my uncle to require the car again. Especially when we all know that he won't need it until it's time to go back to Sutherland on Sunday. What is Wilkins supposed to do with all this time?"

"I imagine he'll retire to his room in the village once dinner starts. Uncle Harold isn't likely to need him after that."

"Uncle Harold isn't likely to need him at all," Christopher said, and moved aside the branches between me and the croquet lawn. "Go ahead, Pippa. Constance."

"Thank you, Christopher."

"Anyway," Christopher added, "I imagine Wilkins will retire to the pub but not to his room, if I'm any connoisseur."

"Connoisseur of what, exactly?"

"Men," Christopher said, with a final look over his shoulder at Wilkins before he ducked through the branches after us. "It's a pity."

"What's a pity?"

He grinned. "That he doesn't incline my way. Good-looking bloke."

"It's just as well that he doesn't," I told him. "Running after the staff is just about the lowest of low tastes."

Constance nodded fervently.

"It's one of the few things I've always appreciated about St George," I added. "At least he stays away from the servants."

"Faint praise, Darling," a voice drawled, close enough that I jumped.

It was St George himself, of course, tucked away in the shade of the stairs, below the terrasse, doing what Wilkins was doing: smoking a cigarette. I don't know how he so often manages to be in a spot to overhear me when I wish he wouldn't.

Unlike Wilkins, he had company. Lady Laetitia was enjoying her own fag through the length of a lovely ivory cigarette holder. She eyed me down the length of it, like I were some lowly caterpillar that had crawled out from the trees and onto the lawn, and had the temerity to speak in her presence.

I ignored her. "St George," I said instead, pleasantly. "I didn't see you there."

"Clearly." He turned his head to blow the smoke the other way instead of straight into my face. "Who would you be running after, Darling, if he were inclined that way?"

"Oh," I began, since he'd clearly misunderstood that part of the conversation. But before I could continue, Christopher got in before me.

"We were talking about Wilkins." He gave Crispin a smirk that could equal one of his cousin's own.

"Is that so?" Crispin's eyebrow rose. "I didn't realize you had such low tastes, Darling."

Laetitia tittered. Constance opened her mouth, perhaps to explain the misunderstanding—it would have been nice after Christopher essentially threw me to the wolves—but before she could say anything, the latter had put out a hand and stayed her.

Crispin watched the byplay, but didn't comment. "What's that you've got?" he asked instead, eyes on the tote over Constance's arm. "You didn't have that earlier."

She lifted it, but this time I got in first. "Abigail Dole's things. We thought Aunt Roz might need fresh napkins for the baby."

He flicked me a glance. "And where did you find Abigail Dole's things?"

"Under the lilac bush," I said. "She must have dropped the bag before she staggered onto the lawn earlier."

Crispin nodded. "So to return to Wilkins…"

"Let us not return to Wilkins, St George. Wilkins is none of our affair. Although, since we're on the subject of Wilkins and of returning, I had him move the H6 back in front of the carriage house for you. You're welcome."

He squinted at me. "Did you talk him into letting you drive?"

Christopher sniggered. I said, "No, St George. I said I wouldn't, and I didn't. Your precious is safe from my clutches. How's your head?"

"My head?" He sounded sincerely confused, which was nice—if something had been wrong with it, surely he would have said so.

On the other hand, it was surprising that he didn't catch on to the reason I was asking. He's usually quicker than that, so maybe something was wrong after all. "What are you implying, Darling?"

"Nothing whatsoever," I said. "Carry on. We'll take the bag to Aunt Roz."

He nodded, looking past me out to the lawn. "Croquet in the morning, I assume?"

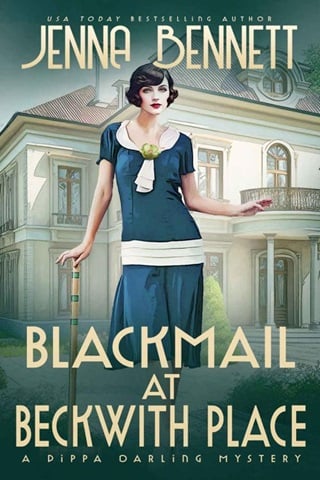

"First thing after breakfast." Beckwith Place has an actual, honest-to-goodness, dedicated croquet lawn, which should tell you how much we all enjoy playing. Or enjoy beating one another, at any rate. As far as I could recall, Crispin had beaten me the last time we'd played each other, and I was eager for my revenge. "Make sure you're rested, St George."

"Of course, Darling." He glanced at Christopher. "You'll be at supper, won't you?"

Christopher nodded. "Pippa's just getting ahead of herself. Looking forward to rubbing your nose in your defeat, no doubt."

"Unquestionably," Crispin agreed. "As I recall, I beat you last time, Darling."

"I know you did," I said. "I'm looking forward to returning the favor." I turned to his companion. "Do you play, Lady Laetitia?"

She looked at me as if I had uttered an obscenity. "Lawn croquet at dawn?"

I smirked. Not, then. "We'll see you at supper, St George. In the meantime, don't do anything Christopher wouldn't do."

"You're awful, Darling," Crispin said. "You realize that that leaves me at loose ends?"

"You could help Aunt Roz with the baby. Get some practice in for the future."

He paled. "I'm not certain I like what you're implying, Darling."

I was quite certain he didn't. Whether that implication was that he'd be responsible for little Bess soon, or that he'd be expected to provide Laetitia with a son and heir shortly.

She didn't like it, either. She gave me a narrow look, and then gave him one. "Crispin? Didn't you tell me…?"

"I did, Laetitia." He flicked her a glance. "Darling's just having some fun."

I smirked. "Whatever you say, St George. See you at supper."

I flounced away, up the stairs to the terrasse with Christopher and Constance trailing in my wake. Constance was wide-eyed and silent, Christopher sputtered like a tea kettle in his effort not to laugh out loud.

"You're evil, Pippa," he told me when we were far enough away that Crispin and Laetitia wouldn't hear him. "You know as well as I do that he's supposed to convince Laetitia the baby isn't his."

Of course I knew. However— "That's his problem. Mine is to keep her from becoming part of the family."

Constance nodded fervently.

"If Uncle Harold is determined to make it happen," I added, "and Crispin won't stand up for himself, someone has to ensure it doesn't come off."

By now, we were inside the house, making our way down the hallway past the kitchen, with no one to hear my outburst except Hughes, who was clattering about with the remains of tea.

I slowed to a stop. "Good evening, Hughes. What's going on with Miss Morrison, if you don't mind my asking?"

She straightened, face blank. "Miss Morrison, Miss Darling?"

"I heard you ask Lady Marsden about her earlier," I said. "Lydia Morrison, Lady Peckham's maid."

A shadow crossed her face and she turned back to the table. "Nothing you need concern yourself with, Miss Darling."

"Constance told me she left Lady Peckham's employ suddenly," I said, with a glance at Constance, who nodded. "She didn't give notice or anything. Was something wrong, and that's why she left? And now you're concerned about her?"

Hughes shook her head. "This is none of your affair, Miss Darling."

"She worked for my mother for as long as I can remember," Constance said from beside me. "If something's wrong, I would like to know."

Hughes eyed her. And eyed me, and eyed Christopher. We both attempted to look as if we weren't asking out of sheer, idle nosiness. Hughes sighed and turned her attention back to Constance. "We corresponded occasionally over the years. I was your mother's lady's maid at Marsden a long time ago. Lydia Morrison was Lady Charlotte's maid at Sutherland before the young lord was born."

The young lord being Crispin. So we were talking about things that had happened almost a quarter-century ago.

"Were you the one who wanted a change of position," I wanted to know, "or did Morrison?"

Hughes eyed me for another moment, but eventually she deigned to answer. "After Master Crispin was born, things at Sutherland weren't the same."

Obviously not. Although she probably wasn't referring to the obvious. People can be so annoying, with the way they don't just come out and say things.

I did my best to look politely expectant, and eventually she gave in and went on. "I wasn't there at the time, but apparently His Grace became… peculiar."

I arched my brows. So did Christopher. "His Grace meaning my grandfather?" he asked. Hughes nodded. "Peculiar, how?"

Normally, when a peer is referred to as peculiar, it's because he has found religion or a chorus girl or some such nonsense. Or has lost his faculties in some other fashion. I had never noticed any such peculiarities in Duke Henry. He'd been a sour old man for as long as I had known him, but I wouldn't have called him peculiar by any of the usual standards.

"Wasn't this right around the time when his own father died?" I asked, looking at Christopher. "The old Duke, the one we talked about, who was a lad around eighteen-sixty? Perhaps your grandfather just had a difficult adjustment into the role?"

Christopher shook his head. "I have no idea, Pippa. I was just a few months old myself at the time."

"So Morrison wanted to leave," I said. "Is that it?"

"Yes, Miss Darling," Hughes nodded.

"And she went to Marsden instead of you, and you came to Sutherland Hall instead of her. Did Duke Henry behave peculiarly towards you too?"

"I never noticed anything amiss in my lord's manner, Miss Darling."

"That's all quite interesting," Constance said politely, in a tone that indicated that she didn't find it interesting at all, "but I would like to know whether there's a reason to worry about Morrison's current whereabouts. This is all ancient history. But she left the Dower House more than two months ago and didn't leave a forwarding address. Do you have reason to think something's wrong?"

Hughes hesitated. "I phoned Dorset the evening after His late Grace's valet was found dead. My lady was uneasy in her mind, and wished to speak to Morrison."

"Aunt Charlotte? Did you hear what they talked about?"

She eyed me again, much as one does an insect on a pin. "No, Miss Darling."

The corollary—"and I wouldn't tell you if I did,"—was implied but not stated out loud.

"Hughes…" Christopher tried.

She shook her head. "I don't know, Master Christopher. She took the call in the study, away from everyone. I stood in the hallway so she wouldn't be disturbed. I couldn't hear the conversation."

"But you think it had something to do with Grimsby's death?"

She gave me another look. "I don't know, Miss Darling."

Fine. "You haven't heard from Morrison since she left the Dower House. And you're concerned."

She nodded.

"Perhaps you can prevail upon your aunt or uncle to make some inquiries," I told Constance, "when they get back to Dorset. Or perhaps Laetitia or Geoffrey would be willing to oblige. It's possible one of the other servants has heard from her. Or perhaps she had friends in the village that she's kept in touch with."

Constance nodded. "I'll let you know if I hear anything, Hughes."

"Thank you, Miss Constance," Hughes said politely. She went back to the tea things, and we headed for the cellar steps and the door into the front of the house.

"You don't suppose anything is really wrong with her," I said, "do you?"

"I can't imagine what," Constance answered, and Christopher nodded.

"It was Aunt Charlotte who did away with Grandfather and Grimsby. By the time Morrison left the Dower House, Aunt Charlotte was already dead. She couldn't have done anything to Morrison."

No, I suppose not. "And Morrison was in Dorset, so she couldn't have had anything to do with what happened at Sutherland."

"I don't see how," Christopher said.

"So why do you suppose Morrison hasn't got in touch with Hughes?"

"Is there any reason she would want to get in touch with Hughes?" Christopher didn't wait for me to answer, just went on. "She'd been working in Dorset for more than twenty-two years. She had no ties to Sutherland anymore. She might not actually like Hughes. She might not have liked Aunt Charlotte either, and that's why she wanted to leave her employ back in 1903. She didn't bother to come to the funeral, did she?"

No, she hadn't.

"It had been twenty-three years," Constance said in her soft voice. "Half her life, probably, since she worked for your aunt. She would have formed new friendships and connections during that time. Sutherland was a lifetime ago."

"She's probably on the beach in Blackpool," Christopher added, "under an umbrella. Or in London working at a dressmaker's shop. Or sitting in a cottage in the Cotswolds with a husband and two stepchildren."

"I suppose." Someone would have to work fast to acquire a husband and two stepchildren in two months' time, but the others were at least theoretically possible. "I don't suppose your mother is likely to know what was going on at Sutherland Hall back then, is she?"

"If she is, she wouldn't tell us," Christopher said. "It's none of our concern, and that's what she'd say. And Uncle Harold would tell us it's none of our concern, and he'd be right."

"And that's if anything was going on at all," Constance reminded me. "We only have Hughes's word for it that something was. Morrison might have wanted a change of scenery for her own sake. Perhaps she had a love affair in the village that went wrong, or something like that."

I made a face, and she continued, "Don't do that, Pippa. Twenty-two years ago, she wasn't much older than we are now. Just because she's a servant, doesn't mean she doesn't have normal thoughts and feelings."

Of course she did. "Fine," I grumbled. "Never mind Morrison, then. What do we do now?"

"I intend to go upstairs to see if I can find Francis," Constance said. "I haven't seen him since tea."

Since he'd stalked off into the house looking for a stiff drink, more specifically. I hadn't seen him since, either.

"I'll take the bag to Aunt Roz," I said, reaching for it. "I'll see you in the dining room for supper, if I don't see you before."

Constance nodded, and headed up the stairs to the first floor. Christopher and I followed the sound of Aunt Roz's voice, and the gurgling of the baby, into the drawing room.

She had spread a blanket on top of the rug, and little Bess was lying on it, kicking her legs, while Aunt Roz sat on the floor next to her. Uncles Harold and Herbert were arranged on the Chesterfield. They each cradled a glass of something amber, possibly bourbon.

"There you are," Aunt Roz said brightly when we came through the door. "Did everything go well, Christopher?"

"As well as can be expected," Christopher said. "Wilkins carried her into the infirmary. Doctor White said she might not wake up until tomorrow, but he'll let us know."

Aunt Roz nodded. "And what's that you've got there?"

"We found it in the garden." I handed her the bag. "It's full of nappies and baby clothes."

"Perfect." She peered into it. "This will come in handy."

I perched on the chair Laetitia had sat on earlier, and Christopher folded himself onto the arm next to me. "There was a note inside, as well." I dug it out of my pocket and passed it to Aunt Roz. "She must have sat on the train and compiled it. The paper has the GWR logo on it."

"What does it say?" Uncle Herbert wanted to know, peering over his wife's shoulder.

Aunt Roz cleared her throat. "Hammersmith Palais. Fair hair. Blue eyes. Black motorcar?—"

Uncle Harold harrumphed, but let her read through to the end before he said, "St George's eyes are gray. And his motorcar is blue."

Aunt Roz nodded. "My boys both have blue eyes. But I imagine gray might look a lot like blue in the dark. And—forgive me, Harold—Crispin would have had access to his grandfather's motorcar."

"The Ballot was black," I added. Uncle Harold gave me a look of concentrated dislike, but he didn't say anything.

Uncle Herbert cleared his throat. "Do we have any idea when…?"

"There's an embroidered blanket in there," I said, indicating the bag; Aunt Roz dove in, "with a name and a date on it. If it's accurate—and I don't see any reason why it wouldn't be—Elizabeth Anne was born in January of this year."

"That would put their meeting sometime in April of last year," Aunt Roz said, peering at the blanket, "if the baby was born at term. This is lovely."

She stroked the soft blanket and embroidery.

"I've been to the Hammersmith Palais de Danse," Christopher said, "although I didn't go anywhere near this girl. But I don't suppose my word is good enough for anyone."

"It's good enough for us, Christopher," Aunt Roz said, with a glance at Uncle Herbert. "We know you'd never…"

Uncle Harold harrumphed. "But I suppose you'll say that Crispin?—"

"Your son does have a habit of tom-catting around, Harold," Aunt Roz said apologetically. Uncle Herbert winced. "You heard what Euphemia said…"

I hadn't heard what Laetitia's mother had said, but I could guess. "He isn't the aggressor in that relationship," I said. "She seduced him, not the other way around."

All three of them looked at me. Four, including Christopher. Uncle Harold's gaze was particularly piercing, and I fought back a wince. It occurred to me, a moment too late, that I had just paraphrased what Crispin himself had told his father earlier.

Now Uncle Harold probably suspected that I had listened in on their argument.

"Sorry," I added. For form, not because I actually felt sorry. "But I watched them together for a full weekend at the Dower House in May, you know, and she's relentless. Ruthless, too. At one point she smacked him across the face with her fan because he wasn't quick enough to cross the room to her."

There was a moment's silence. "Might be just what he needs," Uncle Harold muttered. "A wife who will keep him in his place."

My eyes narrowed, and so did Aunt Roz's. Uncle Herbert's jaw tightened. "With all due respect, Harold?—"

"The boy is out of control," Uncle Harold said. "Someone has to rein him in. If Laetitia Marsden can do it, more power to her."

He put his glass on the table with a sharp click, got to his feet, and stalked towards the door.

"He's not a boy," I told his back. "He's a grown man. You can't make his decisions for him."

He swung around in the doorway to glare at me. "If he knows what's good for him, he'll do as he's told. And so will you, Miss Darling."

He vanished from sight, and we could hear his footsteps slap against the wood on his way across the sitting room and foyer and up the stairs.

Christopher didn't breathe out until there was silence in the room, punctuated by the slamming of a door from upstairs. Bess made an inquiring sort of sound from the floor. "That went well," Christopher said sarcastically.

"Did you expect it to?" Aunt Roz turned to me. "What on earth was that about, Pippa?"

"I overheard him talking to Crispin earlier," I said. "I'm fairly certain he knocked him into the wall a couple of times. Crispin sounded like it hurt."

Uncle Herbert winced again. He's never been the kind of father who disciplined his children with corporeal punishment. "Is he all right?"

"I asked him about his head outside, and he made it sound as if nothing was wrong, so I assume so. I'm still not happy about it."

"And about Lady Laetitia…"

"Harold and Pippa are both right," Aunt Roz said. "Crispin is grown and should be allowed to make his own decisions. But he is running wild, and it's understandable that Harold would support anything that would force Crispin to calm down."

"Not anything," I answered, a bit ungrammatically. "St George would settle down if his father allowed him to marry who he wants to marry. Until Uncle Harold does, I think he's fighting a losing battle."

Aunt Roz had nothing to say to that. Nor did Uncle Herbert. They exchanged a glance.

"Do you need us for anything?" Christopher asked as he got to his feet.

His mother shook her head. "No, Christopher, dear. You two go on upstairs and rest. Supper at eight in the dining room. Black tie."

Christopher nodded and held out his hand to me. "Come along, Pippa."

"Coming," I said, and let him pull me to my feet.

Fullepub

Fullepub