Chapter 7

It took lessthan a second for me to decide what to do. And I suppose I'm not proud of it… no, actually, that's not true. I'm perfectly fine with eavesdropping. As Crispin had told me once, you learn such interesting things.

"I'll be right back," I told Constance.

She opened her mouth, perhaps because she was thinking of saying something to stop me, although if she was, she thought better of it. Instead, she simply nodded, a resigned look on her face, and watched, silently, as I trod over to the door and depressed the latch, as softly as I could.

There was a chance, of course, that Uncle Harold and Crispin had stopped just inside the door, and if such was the case, it wouldn't matter how quiet I tried to be. They'd see the door open and would know that I was there. But if Uncle Harold had taken Crispin somewhere else for better privacy, then I stood a chance of getting inside undetected, and of perhaps hearing something interesting.

So I opened the door as quietly as I could, and held my breath as I eased it open and peered around it.

The boot room was empty. So far, so good.

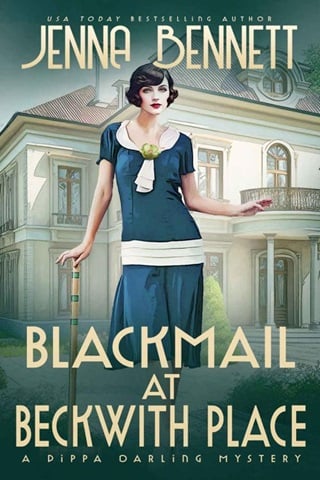

Beckwith Place is a rather small place as far as country houses go. The foyer at Sutherland Hall, for instance, could swallow several of the rooms at Beckwith Place whole. The boot room, obviously, is one of them. It's fairly minuscule, and full of Wellington boots and rain slickers and umbrellas and Uncle Herbert's golf clubs and things like that.

I eased the door shut and made my way across the room as quietly as I could. And stopped in the doorway and contemplated my surroundings.

On my right was the hallway to the terrasse, along with the kitchen and scullery, and the library. On my left was the door to the front of the house, and the stairway down to the cellars. Directly in front of me was the door to Uncle Herbert's study.

Where would Uncle Harold have taken Crispin for a private chat?

Not to the kitchen, obviously. Cook and Hughes were still there. I could hear the faint sound of voices, and of running water and dishes clacking together.

Nor to the library, I thought. They'd have to pass the kitchen door, and Cook and Hughes, to get there, and it was also closest to the terrasse, where the others were. I assumed Uncle Harold would want to avoid an audience for this confrontation, or he would have had it out with his son in front of me and Constance, most likely.

The study, perhaps? It's a small room, tucked away between the scullery and the cellar staircase. Quite private, if you're looking for that type of thing, and I assumed Uncle Harold was.

I crept across the hallway. The study door was open a crack, and there was no noise and no voices from inside. I inched the door open until I could get my head around the jamb, and peered around. The study was dark and empty.

They must have gone into the front of the house, then.

Unless Uncle Harold had yanked Crispin straight down the hallway and back onto the terrasse, of course. That was possible. But if he had wanted to have an actual conversation with his son, they must have gone in the opposite direction.

So I did the same: went to the door that separated the front of the house from the back, and pushed the latch down on the door. I could be a little less careful here, as there was another door between me and the foyer. The little area beyond the first door was essentially the landing for the cellar steps, and the cool draught that filtered up from below was enough to explain the reason for the doors. What was a cool draught now, in the middle of July, was a chill breeze in winter, and Aunt Roz had insulated both doors with felt to keep the cold air from escaping into the rest of the house.

I couldn't hear anything from beyond it.

So I swallowed my anxiety and depressed yet another latch. And eased the door between the cellar stairs and the front of the house open a finger's breadth, holding my breath in case it creaked.

"—idiot boy!" Uncle Harold's voice snarled, so close that he might as well have been standing on the opposite side of the door, and if I pushed it open any farther, I'd hit him in the back. "When are you going to get it through your head that?—"

"Don't you dare call me an idiot!" Crispin retorted angrily, and unlike his father, he took no particular care to keep his voice down. "I am not stupid, I?—"

He stopped talking as something hit a wall nearby with a thump that made the door vibrate. I jumped, and almost let go of it, and caught myself at the last moment, eyes wide. Had Uncle Harold shoved Crispin into the wall? Surely Crispin hadn't pushed his father? Or perhaps he had simply taken his frustrations out with a swing of his fist into it?

"Then stop behaving like it," Uncle Harold hissed. If anyone had been slammed into the wall, it didn't sound like it had been him. "You're damned lucky the Marsdens are still willing to consider you as a suitor for their daughter's hand?—"

"I don't want Laetitia's hand!" Crispin said shrilly.

"You should have thought of that before you ruined her," Uncle Harold snarled. "And furthermore?—"

"I didn't ruin her," Crispin retorted, "you imbecile. I didn't even seduce her. She seduced me! And?—"

"That's hardly something to brag about," Uncle Harold told him, viciously, and there was another thump as something else—or, at a guess, Crispin's back—hit the wall. Again. "And don't you call me an imbecile, you insolent brat?—!"

"Get your hands off me," Crispin said breathlessly. I could hear scuffling beyond the door. "Let go, damn you. Bloody hell, that hurt!"

I winced. Into the silence that followed, I could hear small sounds, like the rustling of fabric—Crispin straightening his clothes, where his father had grabbed him?—and the shuffling of feet. One of them getting away from the other, presumably.

Then—

"I'll hear no more about it," Uncle Harold said. "Stay away from Miss Darling and leave your cousin's fiancée alone. Spend your time with Lady Laetitia instead. And for God's sake, try to convince her that the bastard isn't yours. We can deal with?—"

"The bastard," Crispin said, his voice just as vicious as Uncle Harold's had been earlier, and ice cold, "is, in fact, not mine. I'm many things, Father, but I'm not a liar. When I have a child, it will be born in wedlock, to a woman who's my lawfully wedded wife, and who I won't have to worry is sneaking around behind my back to sleep with my?—"

But before I could find out whether he was going to say groom, or chauffeur, or perhaps cousin, there was yet another thump of something hitting the wall, this one accompanied by a sharp exclamation of pain.

I jumped, and accidentally let go of the door. And because I had, I moved as quickly as I could in the other direction. Hopefully they had both been too preoccupied to notice that I'd been there—had Uncle Harold really knocked Crispin's head into the wall three times? Hard enough for him to cry out?—but just in case they hadn't, I wanted to make tracks before they could find me.

So I scurried through the door into the hallway and from there around the corner into the boot room, and out the door to the driveway.

Nothing had changed in the time I had been gone. Constance was still standing beside the Hispano-Suiza, looking from one side to the other. Christopher and the Crossley were nowhere to be seen. And while it felt like I had been inside a long time, I didn't think it had been more than a minute or two, perhaps three. The row had been vicious and surprisingly violent, but short-lived.

Hopefully Crispin was all right, and Uncle Harold hadn't done permanent damage to him.

I scurried across to Constance and grabbed her by the arm. "Come on."

"What happened?" She stumbled over a tuft of grass as she struggled to keep up with my longer legs. I was still wearing brogues from traveling, while Constance was in delicate strap shoes with higher heels. "Are you all right?"

"I'm fine," I said, and let go of her arm once I determined we were far enough away from the house not to be overheard. "I'm not so sure about St George."

Constance lowered her voice. "What did your uncle do to him?"

Uncle Harold wasn't actually my uncle any more than Crispin was my cousin, but now was not the time to quibble. "Knocked him into the wall. More than once."

Constance winced.

"The first time he seemed to be fine. It knocked the wind out of him and made him shut up, which I assume was the point. The second time he complained that it hurt. The third time he cried out."

Constance sank her teeth into her bottom lip. "That's not right."

I shook my head. No, it wasn't.

"Why did he do it?"

"I don't know," I said. "The first time, Crispin got angry and told his father not to call him an idiot. The second time, he called Uncle Harold an imbecile?—"

"Understandable," Constance said.

I nodded. Understandable that Crispin would be upset with his father after being knocked into the wall, but also understandable that Uncle Harold would object to the appellation. "That's no excuse for manhandling someone, though. And the third time…" I shook my head. "I'm not even sure. They were talking about children. Or about Bess, specifically. Uncle Harold told Crispin that he had to convince Laetitia that Bess isn't his, and Crispin said that she isn't his, and that when he has a child, it'll be in wedlock, with a woman who's his wife and who isn't running around on him with someone else…"

I shook my head. "I can't imagine what there might be about that, that would be objectionable to anyone, especially to Crispin's father. Of everyone, he should be most invested in Crispin having a legitimate heir."

Constance nodded.

"It was probably just his tone. I frequently feel inspired to violence when St George opens his mouth, too." Especially when it's accompanied by a sneer, which it so often is.

"But you don't do anything about it," Constance said.

No, I don't. I might feel like it would be a nice thing to smack the pratty expression off Crispin's face, but I don't actually hit him. We're civilized people, after all, and besides, I'm not entirely certain he wouldn't hit back. He's done it before, after all. And yes, he has been told that it's wrong to hit girls, but when the girl hits first, he can hardly be blamed for retaliating in kind.

"I'm sure he's fine," I said, although between you, me, and Constance, I wasn't as certain as I would have liked to have been. Although I couldn't very well ask him about it, not without owning up to having eavesdropped on the conversation, so there was very little I could do about the whole thing.

"I hear a motor," Constance said.

I dragged my thoughts out of the quagmire they were circling and paid attention. And heard it, too. "This must be them."

We both turned our attention to the road, in time to see the front of Uncle Harold's Crossley come around the hedge and proceed majestically up the driveway towards us. We stepped out of the way and watched as Wilkins… no, as Christopher pulled the motorcar to a stop between the Bentley and the Marsdens' Daimler. Wilkins was in the passenger seat, chauffeur cap pulled low over his face as if he were trying to avoid being recognized.

I turned a chuckle into clearing my throat. "Wilkins, if you don't mind…"

He slanted a look my way.

"Do you suppose you could go and move Lord St George's H6 away from the door? I offered to do it earlier, and he told me, in no uncertain terms, that I was to go nowhere near his precious. But I assume he can't object to you doing it."

Wilkins nodded. "Right away, Miss Darling."

He walked away. The early evening sun reflected in the polished, knee-high boots that went with his spiffy uniform, and burnished the sandy hair peeking out from below the peaked chauffeur's cap.

I waited until he had vanished from sight before I grinned at Christopher. "Talked him into letting you drive the motorcar home, did you? Or did you have to resort to bribery or blackmail to be allowed?"

"Do you know something blackmail-worthy about Wilkins?" Christopher wanted to know, but continued before I could answer. "It took bribery. Although that's an ugly interpretation of an exchange of coins for favors. Naturally he was concerned about what Uncle Harold might say."

"Of course he was." I rolled my eyes. "Uncle Harold is in a foul mood, actually, so it's just as well that he didn't see you. But I might know something blackmailable about Wilkins."

Christopher perked up. "What's that? And why do you say you might, and not that you do?"

"It was over that horrible weekend back in April. Tom told me that Wilkins has—or had back then—a habit of taking the Crossley to Southampton to visit family."

"Not sure that's much of a blackmailable offense," Christopher said, disappointed. "Grandfather might have known all about it, and so might Uncle Harold."

"That's why I said that I might know something, and not that I do for certain. Wilkins might have had your grandfather's permission. He seemed to treat the staff better than he did his own family, at least judging by Grimsby. Although I doubt Uncle Harold would put up with the chauffeur taking off on personal errands whenever he felt like it."

I had never had a high opinion of the old Duke's personality—stingy, hard-necked old man that he was—but over the past few months, I had developed an even lower one of his successor.

And Christopher could tell by the sound of my voice that something had happened, I assume, because he asked, "What's he done now?" in a resigned sort of tone.

"How do you know that he's done something?"

"I know you," Christopher said, which was certainly true. "You only get this way when someone does something you deem unfair or unjust."

"Well, your uncle abused your cousin again."

Christopher's brows lowered. "How do you know that?"

"Followed them inside and eavesdropped," I said. "Uncle Harold kept grabbing St George and knocking him into the wall. Or at least that's what it sounded like from where I was standing."

"What did Crispin do to deserve it?"

I gave him a look. "Do you think anyone deserves being knocked about by their father?"

"Of course not, Pippa. But you have to admit he can be quite trying."

I grimaced. "He shot his mouth off. You know how he is. But that's no excuse, Christopher."

"Of course it isn't," Christopher said. "What do you want me to do about it?"

It was an actual question, not the rhetorical kind that implied that I shouldn't expect him to do anything at all, and I could have kissed him for it.

However— "I don't think there's anything you can do," I admitted. "Crispin's supposed to devote himself to Laetitia, and to making sure she knows that the bastard—direct quote from your uncle—isn't his."

Christopher rolled his eyes.

"See if you can get a look at his eyes, at least."

"His eyes," Christopher said blankly. "I'll admit they're pretty, Pippa, but you want me to stare deeply into Crispin's eyes? Why?"

Constance let out a titter, and then flushed when we both glanced at her.

"I'd do it myself if I could," I said. "And don't look at me that way, you know what I mean. But Uncle Harold warned him away from having anything to do with me, or with Constance. Laetitia only."

"Yes," Christopher repeated, "but why?"

"Because if Uncle Harold kept knocking his head into the wall, he could be concussed. He said it hurt."

Christopher pressed his lips together, but nodded. "I'll see what I can do."

"Thank you."

We all three looked up as the front of the Hispano-Suiza, with the stork emblem and the name in ornate script across the grille, rolled slowly up the driveway towards us.

"We'd better move out of the way," Christopher said. He grabbed me by the wrist and Constance, a bit more politely, by the elbow, and moved us aside as Wilkins slotted the H6 into place next to the Daimler.

"Thank you, Wilkins," I told him as he exited the car and shut the door behind him.

"No problem, Miss Darling." He tugged on the brim of his cap before disappearing into the carriage house with long strides.

I tucked my hand through Christopher's arm. "Enough about St George. Did anything interesting happen in the village?"

Christopher offered Constance his other arm, and she put her hand on it, too.

"Not aside from what you might expect. She didn't wake up on the drive. I held onto her as best I could. Wilkins carried her into the infirmary. He's a strapping lad, isn't he?"

He was, and no lad, either. Older than Francis by at least a year or two, and with the same broad shoulders and muscular arms, most likely honed on the Continent during the war. A decade older than Christopher, I'd say.

He was certainly attractive, if one happened to like the type. And Christopher might. Although Wilkins wasn't the sort to appreciate Christopher's charms, I thought.

The latter shook his head when I said so. "Certainly not. Nor was that why I brought it up. I had to haul her out to the car, you know, and for all that she's small and skinny, it's no easy task. But Wilkins scooped her up like she weighed nothing. He even got a little grunt out of her, and I think her eyes opened, but if she woke up, it was only for a second. Once he'd put her on the cot in the infirmary, she was out cold again."

"Did Doctor White say anything interesting?"

Christopher shook his head. "Just that he'd take care of her, and let us know when there's a change. He said we'll probably hear from him tomorrow morning."

I nodded. "Nothing to do but wait, then."

"I suppose not." He looked around, at the bushes and trees and the croquet lawn where Abigail had swooned earlier. "I wonder how she made it here from London."

"I imagine she must have taken the train to Salisbury," I said, "like we did, and either walked or hired a car from there. Perhaps begged a ride with someone part of the way. A young woman on foot carrying a baby might appeal to someone's better instincts. And I don't imagine she was flush, really." Not judging by the out-of-date frock and the fact that she couldn't have been eating well lately.

"Seems a long way to come without some sort of luggage. Or a bag with extra nappies for the baby, if nothing else."

It did, now that he mentioned it.

"Might she have dropped it?" I asked, looking around. "Before she lurched onto the lawn and fainted?"

"I suppose she might have done."

"Should we look, then?" There was no part of me that wanted to go back onto the terrasse only to watch St George try to please his father by buttering up Lady Laetitia and her parents. I understood why he'd do it—Uncle Harold held the purse strings, as well as the title and all the power—but I still didn't think I wanted to watch.

"No reason why not," Christopher agreed, looking around. "She would have come up the driveway, I assume, the same way we are. And she came through the bushes… over there, was it?"

He indicated a break in the foliage up ahead. We could just hear the buzz of discourse on the terrasse from where we were standing. Not clearly enough to make out individual voices, but the general rise and fall of conversation.

I nodded. "Looks like."

"Let's look about, then. She would have traveled light, I assume, so probably not a trunk or weekender bag…"

No, Abigail had had the baby to carry. She would have been traveling quite light, I thought. No weight that she didn't need, since she had a fifteen pound baby on her hip and wouldn't want to carry anything else unless absolutely essential.

"Over there?" Constance ventured hesitantly. "Under the bush?"

She indicated a healthy specimen of lilac, seven feet tall, leafy green, but with no flowers left in the middle of July.

"Good eye," Christopher commented. He started forward, and we both withdrew our hands from his arms to let him proceed. A moment later, he had pulled a cheap cloth tote from under the branches and extended it towards her. "Your discovery, my lady."

Constance took it, but looked reluctant. "Do you think we should go through someone else's personal belongings?"

"Aunt Roz will need nappies for the baby," I pointed out. "It's long enough since Christopher was small that I'm sure she doesn't have any sitting around. And if there's anything in there that'll give us an idea of what's going on, I think we owe it to ourselves to find out. Don't you?"

She hesitated.

"It could exonerate Francis. She might have something in there that proves, without a doubt, that he isn't responsible."

Of course, there could be something that proved, without a doubt, that he was responsible, as well. But Constance didn't seem to think about that. Her lips firmed. "Here? Or should we take it somewhere?"

I glanced around. The door to the boot room was nearby, but so was the carriage house, and aside from Wilkins's presence, it might be more private. "In there."

Christopher shot me a look. "Why are we hiding, Pippa? We're not doing anything wrong."

"Just humor me," I told him, as I headed for the row of cars again. "I don't want everyone to see. Not until we know what we're looking at. Although you're right, there's no reason to hide. Let's just stop beside one of the cars and use the seat to lay out what we find."

Christopher shrugged, but acquiesced. When we got there, he was the one who opened the door to Crispin's blue H6 and gestured Constance forward. She placed the tote on the seat and bit her lip.

"Would you like me to do it?" I asked.

She slanted me a look. "Would you? It's really more your place than mine."

I wasn't sure it was anyone's place, but I also wasn't about to let the opportunity go by to see what Abigail was carrying. Call it healthy curiosity, although I have been told, more than once, that I have a tendency to stick my nose into things where it has no business being.

Nonetheless, I turned the tote upside down and shook it. A shower of small items dropped and fluttered out and hit the seat, and a few bounced off.

"Coin purse," Christopher said, as he fetched it from the floor of the Hispano-Suiza. "Ticket stub. Third class fare from London to Salisbury."

I nodded, as I sorted through the things on the seat. "Nappies. A change of clothes for the baby. A blanket."

It had ‘Elizabeth Anne 1-14-1926' embroidered in one corner, surrounded by small, blue flowers. I squinted. "Violets?"

"Looks more like forget-me-nots," Christopher said, not that he knows much more about flowers than I do. "Pretty, whatever they are."

It was. A christening-gift, perhaps, or something for when the baby had been born. It was clearly not off the rack, but something a friend or relative—or Abigail herself—had made, perhaps while she'd been waiting for little Bess to be born.

"There's something written on this, too," Constance said, holding up a small piece of paper that had been folded a few times, and now unfolded again. Christopher and I crowded in.

At the top of the page was the logo of the Great Western Railway, the shields of the cities of London and Bristol. Below, in round, somewhat unformed script, was a list of words or phrases.

Hammersmith Palais

Fair hair

Blue eyes

Black motorcar

Grandson

Duke of Sutherland

Astley

Fullepub

Fullepub