11. Declan

Chapter eleven

Declan

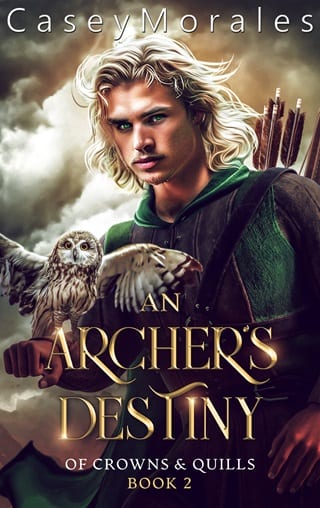

T he sun I'd thought so lazy the day before climbed above the ocean with haste the next morning. I was slow to stir, but my feathered companion rose with the sun, full of energy and life. She leaped onto my chest and began hopping and peeping.

"All right, all right. I'm getting up," I said, peering at her through bleary eyes.

She stilled but gave me one last peep before jumping down and scampering off into the foliage.

I stowed my bedroll and rummaged through my pack, disappointed to find only a handful of nuts remained of my rations. I chased them with a few swallows of wine from the cave and suddenly felt awake and well fed.

"It will be a shame when the wine is gone," I said, shaking my skin to test how much remained.

The owl returned with another lizard, this one twice the size of the last. She strutted up to me and tossed it at my feet, where it twitched, badly injured but still clinging to life.

"Uh . . . no thanks. Those nuts filled me up." I tried not to wrinkle my nose at the idea of eating the thing.

She peered up, then back to the lizard, then back up at me again. After an eternal, unblinking stare, she tilted her head and peeped, then snatched her meal and scampered a few paces away to enjoy it by herself.

The closer we came to the ocean's edge, the more the foliage began to thin. Ferns faded away, and the plants whose leaves resembled the flopping ears of elephants grew sparser. As the sun passed her peak, we stepped onto the edge of the village, entering through the back of several buildings that lined what appeared to be a main road. Thatched roofs covered huts of wood and bamboo. Most of the buildings were fronted by wide, covered porches, but few entrances were barred by doors.

We passed a wire-thin farrier and a burly blacksmith, a gap-toothed old man and a silver-haired woman spinning pottery, and several small shops selling fruits, vegetables, and fish. One shop offered jewelry made from shells, pearls, and other ocean-dwelling creatures. Each person we passed bore skin the color of the darkest night. While some nodded at our approach, most glared, their gazes guarded, as if curious. None smiled or offered warmth in greeting.

As we turned onto a wide, gravel-strewn road, we were greeted by a two-story box made of wooden planks painted in cheerful sky blue. Faded yellow lettering scrawled across a wooden sign nailed above the door that read, "The Dancing Gull."

If not for the fish netting, rods, and other oceanic decorations clinging to the ceiling and walls, I might've thought we had stepped into a tavern in Melucia. Only two of the tables held patrons, one ancient couple whose skin had been baked to a crisp by the island sun, and a trio of heavily built men in overalls. A tall, thin man with the body of a stork but the eyes of a hawk stood behind the bar. His hair was a wiry black jumble that sprouted in every direction, accenting his already soaring height.

As we strode through the room toward the bar, everyone stopped eating and stared. I couldn't decide if I'd drawn every eye because I was an obvious stranger to the village, the tiny woodland owl perched on my shoulder, or the paleness of my skin. Their gazes weren't hostile, but there was a keen wariness in their eyes. I knew what being an outsider felt like—I'd spent my whole life playing that role—but this was a different sort of isolation and scrutiny.

The tall bartender glanced up from the mug he'd been polishing with a dingy rag. "Welcome t' the Gull," he said with a musical lilt. "What can I get for ya, my friend?"

"What's good for lunch?" I asked, glancing back at the old couple's table filled with platters and bowls.

"Ya must be new t' the Isle. We have fish, or ya might try the fish, and on the morrow, we have fish." The man's laugh sang throughout the room, though his broad smile failed to reach his eyes.

I flashed a smile. "Well, I guess I'll try the fish. Would you mind putting a small piece of raw fish on the side for my friend?"

The barkeep's eyes settled on the owl, widening slightly, before returning to me. "Of course, of course. Never seen a little bird like t'at on the island before."

"We've traveled far together," I said.

The man resumed wiping his mug. "What brings ya t' our island, my friend?"

I knew this question would come but was surprised when the bartender asked so openly. His head remained bowed over the dirty mug, but he peered up at me.

"We're here looking for help with some . . . family troubles back home. My, um, uncle . . . sent me to ask for guidance," I fumbled.

The man continued cleaning, his eyes never straying from mine. "And who on our island would be helpin' a family on the mainland?"

"Well . . . uh . . . I don't know exactly."

The man set the mug in front of me and stared for a long moment before filling it with ale. "Gonna be hard for somebody t' help ya if ya don't know who you be askin'."

I nodded and raised the mug to my lips.

The owl hopped off my shoulder onto the bar and stared up at the tall man. He looked down and laughed again, and this time genuine warmth rippled through his smile and crinkled the skin around his eyes.

"Curious little t'ing," he said. "I'll go get yer fish."

As soon as the bartender left the room, the other patrons, who had been watching and listening with unguarded interest, resumed their meals. I turned as the trio of muscled men huddled and whispered across their table. One stood and exited the inn, leaving the other two to finish their meals. Something in the back of my mind screamed that they were trying a little too hard not to look in my direction as they ate.

Turning back to the bar, I tried to hide my discomfort with another sip of ale and was rewarded with a light, fruity flavor. It was unlike any of the dark ale I enjoyed back home.

A short time later, the bartender returned with a steaming pile of flaky white fish and a bowl of fried fruit for me, then set a smaller plate containing a filet of raw fish before the owl.

"That fish is as big as you are, little one." I laughed as she struggled to pull it away. She promptly dropped the fish out of her beak, looked at me, and gave a harsh peep that made me laugh even harder. Under the owl's scrutiny, I reached over and tore the fish into smaller pieces. The moment my hands left her plate, she attacked her first bite as though it might swim away if she ate too slowly .

Neither of us noticed the bartender following our exchange.

When the man spoke, his voice echoed with obvious surprise. "T' bird understands ya."

I shrugged and grinned. "It sure looks that way sometimes."

We were halfway through our meal when the main door cried as it flew open and three more men in fishing overalls entered. When I turned, I recognized the one in the middle as the man who'd left earlier.

"Ya need t' come wit' us, mainlander ." The man spat the last word with obvious contempt.

I finished chewing my bite before raising both palms in a gesture of surrender. "Easy, friends. We came here for help, not trouble."

"Yer kind always bring trouble. Now git up. Yer comin' wit' us, one way or the other."

I kept my hands raised and stood slowly. Without a word or command, the owl hopped onto my arm and raced up to perch on my shoulder, where she peeped angrily at the men.

Before we could move, the barkeep spoke. "Take them to Larinda."

The fisherman asked, "Why do we honor t'is man? He needs t' leave the Isle before somet'in' bad happens."

The barkeep glared, then placed both hands on the bar and vaulted over to land between us and the men. He planted both fists on his hips and stretched to his full height.

I was so startled that I stumbled backward into the bar.

"It's not him. It's the bird. Larinda need t' see the bird," he said, never breaking eye contact with the burly fisherman. His words were precise and deliberate, as if each carried the weight of a thousand ships.

The brows of the fishermen rose as they gaped. I had no idea what was happening or what the man's words might mean, but I was fairly certain the bartender was attempting to help, so I remained still. Even the owl quieted, swiveling her head from the bartender to the men.

The men huddled and whispered for a moment before turning back and nodding. The one who'd spoken took a step forward. "As ya say. Larinda will decide what's t' be done."

The bartender turned to us and stared at the owl on my shoulder, then whispered without moving his eyes from her. "Go wit' these men. They will take ya t' Larinda. Ya will be safe till she decides what t' do wit' ya."

The man shifted his gaze from the bird to me, eyes hard and unwavering. I held his gaze a moment, then nodded, grabbed my pack, and followed the fishermen toward the door. The two men still sitting at their table rose and joined the escort, trailing behind us.

In an odd juxtaposition to the island and its people's relaxed appearance, there was a formality to the way these men shepherded us down the street. A handful of onlookers peered from porches and windows, their eyes widening at the sight of the pale-skinned man at the center of the storm. I felt like a condemned prisoner being taken to the gallows.

The owl cooed and nuzzled my neck, unfazed by the circus around her.

We marched thirty or so paces before the road ended at the steps to a small rectangular hut held aloft by thick stilts. To either side of the structure were rings of smaller oval huts that reminded me of eggs poking halfway out of the ground. They bore a strange symmetry I suspected held some deeper meaning to the locals, though I couldn't fathom what that might be.

Beyond the outer ring, two sprawling docks stretched like wooden fingers over crystal-blue waters. Small fishing boats dotted the shoreline, but there were no larger ships the docks were built to accommodate.

As we climbed the steps to the main hut, I noted its construction differed from the other homes and shops we'd seen since entering the village. The roof, walls, and floors were made of several layers of tightly lashed bamboo. Blanketing the bamboo roof were large interlocking tiles I was used to seeing on Melucian houses. As we entered, I found that the bamboo structure surrounded an oval courtyard that consumed most of the structure's interior .

The men escorting us had to prod me to continue walking as I stopped in the doorway to gawk at the tropical paradise of the courtyard. Flowers and palms of every variety filled the area with sweet scents and brilliant colors. A cobblestone path led from the door to a clearing at one end of the garden, where several chairs and small tables lay scattered.

In the center of the tables and chairs, a high-backed bamboo chair held court. It reminded me of the seats of power used by the Triad back home, less refined yet somehow more regal. A frail-looking woman with wiry gray hair and luminous brown eyes lounged upon it. Her skin, stretched taut across spindly arms, was dark and rich, while that of her face was losing its battle with wrinkles and creases thanks to years baking beneath the island's sun. As we approached, the woman's eyes passed over me, fixing instead on the owl perched on my shoulder.

We stopped a few paces from the woman. The men offered no bow or other gesture of obeisance, but it was clear who was in charge.

One of the men leaned near my ear and whispered in a quiet, dark voice, "Ya stand before Larinda, Mother of t'is Isle. Don't move from t'at spot and show respect, and she might let ya leave in one piece."

The elder turned her gaze to me and scowled. "Who are ya, and why are ya disturbin' our peaceful shores?"

Her voice carried the rasp of age but the steel of one accustomed to being obeyed.

I offered a deep bow in the mainland style. "I am Declan Rea, a Ranger of Melucia. Arch Mage Velius Quin and Mage Atikus Dani sent me in search of aid."

Larinda's scowl deepened. "Ya've seen our village. What kinda help do ya think we have t' give ya? We want no part in mainlander foolishness."

I sucked in a breath. I'd played this conversation in my mind a hundred times over the past few days, but it never went like this. I didn't know if I could trust this woman but didn't see any other options.

Here we go . . .

"I seek the Keeper's aid."

Everyone—and everything—froze.

The gentle breeze tickling the flowers and palms stilled. The sounds of waves crashing and the cawing gulls quieted. In a blink, nothing existed except the old woman, the owl, and me.

Larinda rose from her throne and planted her fists on her hips as the barkeep had. Her head rose to my shoulder; yet, in that moment, she towered above us.

"What do ya know of t' Keeper?" she asked with narrowed eyes.

Before I could respond, the owl peeped several times and hopped from my shoulder onto the path, then bounded over to Larinda, where she began tugging at the woman's linen trousers.

Larinda, startled by the sudden movement, gawked as the owl released her pants and uttered another stream of peeps.

The old woman staggered back and slumped onto her throne, her mouth agape and eyes wide. The tension that had built only moments earlier dispersed, and the sounds and breath of the ocean filled the courtyard again.

"Dear Spirits of t' Deep!" Larinda covered her mouth and stared down as the owl climbed up her leg and perched on her lap. The woman cupped both hands to her mouth and broke into childlike laughter as tears fell onto her cheeks.

"Yes, dear one, it is good t' see ya again after so long!" She stroked the owl's head.

My brows peaked with wonder. The barkeep had mentioned that Larinda would want to see the owl . . . but I could never have imagined this turn of events. The woman spoke to the bird as though meeting a long-lost relative.

"Ya done right t' bring 'em t' me," she said to the men behind me. "Now, leave us alone t' talk a while. We be fine."

They glanced at each other, then back to Larinda, who made a shooing motion with her hands. "I said go. What ya waitin' for? "

As the men retreated, Larinda motioned to me. "Drag t'at chair over here. We need t' talk."

My head spun, but I did as I was told.

I sat in silence as the old woman fussed over the owl. There was a familiarity—no, an intimacy —to their interaction. I saw it in the bird as much as in the woman. They were gentle and affectionate, as only those who'd lived a lifetime together could be.

I couldn't take the silence any longer. "How . . . How is this possible? You know her?"

Larinda continued stroking the owl, never looking up, a broad smile creasing her wizened face. "Young man, I'd know t'is beautiful Spirit anywhere."

My jaw dropped.

To invoke the Spirits—a Spirit—when speaking of another? A bird? It was blasphemy.

Larinda's eyes rose. "When did she bond wit' ya?"

"Bond? What does that even mean?" It felt as if this woman had switched to speaking in a language made of grunts and growls that no man could understand. My head swam as I grappled with her implication. Then something she'd said echoed in my thoughts. "Wait . . . you said ‘after so long' a minute ago. She can't be more than a month or two old, and there's no way she traveled from Melucia to this island in that span. How could you possibly know her? "

The woman laughed again, a rough yet joyful sound reminding me of a battered chime the Mages hung at the entrance to their living quarters. "Ya really don't know, do ya? She's órlaith, t' Golden Princess. She has always been and will always be, so long as magic flows through our world."

"órlaith? The golden what?"

"Ranger Declan Rea, I don' know why, but t' Daughter of Magic has chosen you for her Bond-Mate."

Fullepub

Fullepub