Chapter 16

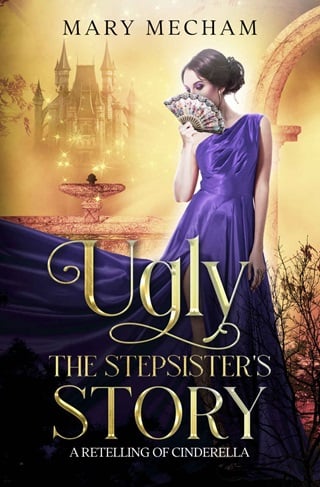

Finally, after weeks of care and smelly pastes and creams, I had healed. I had full use of my left arm again, and all my bruises from being thrown from Storm were gone. There were still scars that ran ragged and red all over the left side of my face, and the court physician assured me it would fade over time, but I didn’t believe him. I knew his words were shallow, full of false hope for the fools who believed such lies.

I knew what I looked like; I was hideous. Mother and Comfort would give me their painful smiles and tell me they could barely even see the difference, but if it bothered me, they would buy me a whole stock of cosmetics, and that looks didn’t matter anyway. It is easy for someone pretty to say that.

I shunned mirrors. I never looked at myself. I couldn’t. The image made my stomach churn sickeningly. Anytime I would accidentally glimpse my reflection, I would have painful, vivid flashbacks to that horrible day in the woods. To the man with the scarred face shouting, “Who wants to have some fun boys?” as the mob closed in around me. I felt the overwhelming, frantic panic take over my body. I re-lived the all-consuming pain that the burns had inflicted on me.

When I had worked up the courage to ask about Storm, I was told that she had disappeared, either killed or stolen.

I could still recall with perfection the sensation of my hands loosing arrows into the oncoming hoard of men. I could still see the faces of the men I hit with those arrows. I wondered if I was the cause of some families now being fatherless, as mine now was. Anytime I thought about Father, I heard the pain in Comfort’s voice as she whispered, “His funeral was yesterday.”

I never even saw Father or got to say goodbye.

Father. The one who always knew how to cheer me up. The one who always looked out for us. The one who loved us fiercely and was protective of his daughters. If he had lived, surely he would have saved me. I couldn’t imagine life without Father. I wanted him there to tell stories that would turn gloomy evenings into adventures, to feel the security of knowing he was always there to give me guidance and reassurance.

But now, frequent panic attacks would leave me huddled in the corner, rocking back and forth on my heels, tears pouring from my eyes—one normal and the other scarred with pinched, taught skin. My breath would come in short, panicked bursts that deprived my brain of oxygen and left me even more inconsolable than at first.

I was ugly. I knew it.

I knew I must be revolting to look at, whatever Mother and Comfort pretended. I refused all visitors.

Curtis came to call several times, but I never allowed him in. Comfort would come back to my room, say that Curtis was here to see me, and ask if I wanted to see him. Every time, she would hand me the flowers, or notes, or whatever he had brought to try and make me feel better.

But I preferred to stay alone, in my darkened room, avoiding all contact with the outside world. I never read Curtis’ letters, just let them pile up on the bedside table where Comfort dropped them.

I know Mother would have tried to cheer me up if she could, but she stayed in bed for days at a time, crying uncontrollably, grieving over the loss of Father. She barely ate, rarely slept, and looked like she had aged a decade in just a few weeks. Shadows were constantly under her eyes, and her eyes looked deadened. She grew pale and bony. She had always been thin, but now became skeletal, her face sunken and hollow.

Comfort was the only functioning member of our family now. As Mother and I withdrew from the world, Comfort was the one bringing us meals, reading us fantasy novels aloud to try and take our minds off our suffering. She was the one taking on the whole burden of nursing a damaged sister and grief-stricken mother back to health. The task seemed to harden her. I never saw Comfort cry. She seemed determined to be strong enough for all of us. Day in and day out, she would chatter away about the weather outside (I always kept the shades tightly drawn), or what the cook had said about his granddaughter, or about how the rumor was that Hubert had given a speech so lengthy and dull that the king himself fell asleep.

It seemed impossible to me that life was still moving on for people outside of our chambers. That there were still people who woke up and went about their day, not knowing or caring that Father was gone. For Mother and myself, nothing mattered anymore.

Fullepub

Fullepub