Chapter 19

19

Messages

9:17 AM

Me

On my way to Kyoto. Might not be back stateside for a while.

Noora

Jealous. I just ate an entire pizza in my underwear.

Glory

Whoa.

Hansani

A lot to take in here.

Me

I miss you guys.

Noora

Ditto. Japan has stolen my best friend. Totally heinous anus.

Glory

That’s not a saying.

Noora

Well, I’m making it one and I’d love your support.

Me

Anyway … you all mad?

Hansani

Of course not.

Glory

Nope. Some horses are meant to run free.

Noora

Just don’t be a stranger, okay?

Me

Got it. One more thing?

Noora

Yes.

Me

If you all were trees, know what kind you’d all be?

Glory

If this is a pun …

Me

… tree-mendous.

Noora

I’d totally go out on a limb for you.

Glory

Please stop.

Hansani

What happened with hot bodyguard?

Me

Ugh. Don’t ask. Made a fool of myself. Now it’s beyond awkward. That’s what I get for trying to branch out.

Noora

Don’t worry I’m here. I won’t leaf you alone.

Glory

You two actually need help.

I smile at my phone, lean back in the plush velvet seat, and listen to the click-clack of the train as it speeds toward Kyoto. We’re in a private carriage—me, Mariko, Mr. Fuchigami, and a security team headed by Akio. As for the imperial guard, he’s made himself scarce. Naturally, I don’t jump every time a door between the cars opens or shrink in my seat hoping to avoid him. That would be pathetic. I’m not a total sad sack. Just kidding. I am. I really am.

My phone buzzes in my hand. It’s my father texting: Departure okay? I tap out a three-letter response: Yep. Instead of informing him myself I’d be going to Kyoto, I had Mr. Fuchigami do so. Now we communicate purely by text. Just call me Petty LaBelle. He may have posed Kyoto as an opportunity to learn, but it’s hard not to feel as if I’m being hidden away. You know, the whole thing where imperial families ferret unwanted members to the countryside and abandon them?

I put my phone away and stare out the window at Japan’s countryside, watching the scenery zip by at 320 kilometers per hour. Mount Fuji has come and gone, as have laundry on metal merry-go-racks, houses plastered with party signs, weathered baseball diamonds, an ostrich farm, and now, miles of rice paddy fields tended by people wearing conical hats and straw coats. Japan is dressed in her best this morning, sunny and breezy, with few clouds in the sky as accessories. It’s the first official day of spring. Cherry blossoms have disappeared in twists of wind or trampled into the ground. Takenoko, bamboo season, will begin soon.

Mr. Fuchigami sits across from me. He nods to the window. “See how the villages huddle together?” I do notice. They’re clustered, surrounded by rice paddies or farmland. “Not many people live in higher altitudes. The mountains are the domain of the gods,” he says. Shinto is the state religion. My grandfather, the emperor, is the head of it—the symbol of the State and the highest authority. “Even today, it’s considered taboo to live so high.”

At the word taboo, I remember my last conversation with Akio. I stand abruptly. “Excuse me.” I skirt away, heading for the door.

In the bathroom, I wash my hands and contemplate splashing water on my face to see if it will cool the lingering burn of embarrassment, but Mariko spent half an hour on my makeup this morning. I wait a few minutes, letting my body sway with the train’s movement. There’s something soothing about the rocking. Alas, I can’t stay here forever.

I hit the button for the door and it slides open. My head is down. I’m not looking where I’m going and I run right into a solid body. Eff my life. It’s Akio. Sadly, my imperial guard is just as handsome as ever, but a little broodier. Even better.

“Your Highness.” His voice is dry. So formal. “I didn’t see you.”

I can’t quite look at him. I don’t want to. The eyes are the windows to the soul, after all. “Right. I’ll make sure to alert you of all my future movements.” It’s a bit snippy. A lot snippy. But the best defense is a good offense. And that’s all I know about sports.

His unsure gaze searches my face. “If you would like another imperial guard, I would understand. A replacement can be here—”

“I don’t think that’s necessary.” I lift a shoulder, doing my best to convey through body language that what happened between us means nothing at all. “No reason we can’t still work together. I’ve forgotten about it already.” Lie. Big lie. I haven’t forgotten. I cannot forget. I still have your sweatshirt. I still can feel your hands on my waist, the way your fingers dug into my hips. “It was a mistake. A misunderstanding.”

His lips press together. “Right.”

The connecting car door slides open. “Izumi-sama, lunch is about to be served.” It’s Mariko.

“Sumimasen.” Akio bows. “I’ve a security briefing to lead.”

I try to smile, but I’m pretty sure I fail. Akio stares at me for one agonizing moment, then leaves. Mariko watches him. I give myself a pat on the back for keeping my eyes trained on the window. Small steps.

“Everything okay?” She frowns, searching my face. “You seem a bit off.”

“Just peachy,” I respond tightly.

She takes a deep breath. “Akio’s in a mood today.”

“Yeah.” I straighten. “Are you hungry? I’m hungry.”

I breeze past Mariko. Lunch is placed in front of me. A bento box. Akio stands at the back of the train. No, I will not look at him. But do I feel the weight of his stare, or is it just wishful thinking? My neck heats. I glance back. Oh, he’s watching me, face blank. I remind myself this is his job. That’s all he’s doing. No need to read into it.

A distraction is necessary. I could spend the time on homework. I’ve arranged to finish up my classes online. But instead, I reach into my bag—some designer purse that looks like a large envelope with handles—and pull out my headphones. I plug them in and listen to hip-hop and “The Rose,” the song Akio and I danced to.

The music drowns out the sound of the train, the rustling of Mr. Fuchigami turning his newspaper, the chatter of Mariko on the phone, and most importantly, my thoughts.

I let out a frustrated breath, ball up the piece of parchment paper, and toss it to the side. It’s late, the hour nearing midnight. Lights are turned down low. I shiver in the drafty room. Built in the late 1800s, the Sentō Imperial Palace was refurbished, but kept all of its ancient charm and appeal—a tiled roof that swoops into elegant curls, huge wooden exterior doors, floorboards cut from rare keyaki wood, and golden screens separating rooms. If I am to find my Japanese soul anywhere, this would be the place. There are no tabloids here, no high-profile events, no distractions.

My hands are stained with ink, and the blue Nabeshima rug is littered with my sacrifices. I’ve been practicing kanji at a high table for hours. The house retired long ago. I am alone with all my failures. Picking up another sheet of washi paper, I place it on a cloth and weigh it down with a polished stone.

I dip the brush in ink. Making ink—grinding powders, mixing colors (golds, silvers, azurite), and adding glue—can take hours. Someday, I might be able to do this. But it’s a master’s skill, and I am a novice. It is the way of kata, the practice of doing something over and over again until it is second nature. Calligraphy is part of the imperial identity. Therefore, it is part of mine now.

I draw the brush downward, creating the first stroke for the word mountain, yama. It ends in a giant splotch. I drop the brush, and ink splatters all over the paper. Another one bites the dust.

“You’re overthinking it.” It’s Mariko. Her pinstriped pajamas are buttoned all the way to the top.

I startle. “I didn’t think anyone else was still awake.” She hesitates at the door. Inwardly, I sigh. “You hungry?” I gesture to the plate of dorayaki pushed to the corner of the table.

“I could eat.” She shuffles forward and joins me at the table. We nibble in silence for a while. Mariko’s serious face glows in the lamplight. “May I see?” She edges the piece of paper with the ruined script toward her.

I squirm in my seat. She studies my handiwork and doesn’t try to hide her displeasure. I actively wish for the power to light things on fire with my eyes. “I knew it. You are overthinking. Because of this, you are too heavy-handed. You are forcing the lines rather than letting the lines be the force. Let me show you.”

She takes up the brush, dips it, and, on the same piece of paper, executes the first stroke. “Do not think about the character you’re making. Only think about the line, the single movement. It’s like a dance, ne? If you concentrate too much on the final steps, you will miss the present ones.” Another stroke, one more, and she has completed the pictograph. It is beautiful, worthy of hanging on a wall, and I say so.

She shakes her head. “I still have much to learn, but it is passable. It doesn’t have to be perfect, however. Kanji is an expression of the soul.”

I fiddle with the edge of the paper. “It’s overwhelming how much there is to learn.”

She nods. “I understand. When I came to Japan, it was quite intimidating.”

I inspect her, surprised at this news. “You weren’t born here?”

“No. I was born in England. My father is Japanese. My mother is Chinese. We moved here just after I turned five.”

“I didn’t know that.” How could I not know that?

Her brows draw tight. “You never asked.”

“I bet you were fluent in Japanese, though.”

“I knew some,” she says. “But my entire education had been in English. When we arrived, my parents enrolled me in St. Peter’s International School in Tokyo. I had to learn everything from scratch. Worse, I was terribly made fun of. Children can be so cruel.”

I think of Emily Billings in an almighty rush. All the nice things anyone has ever said to me are dust in comparison to that one moment in time. I gulp. “How did you manage it?”

She stares at the table. “Some things you just get through. I was near proficient by the end of kindergarten.”

My mouth quirks upward. “You really do learn everything you need to know in kindergarten.”

“And sumo. I used to watch with my nanny and practice the wrestler names.” She taps the paper. “Mountain was a personal favorite.” She sighs. “I blend in most of the time. But in some ways, I will always be a foreigner.”

“I insulted the prime minister,” I blurt. “Asked him about his sister not attending the wedding. And as I was leaving, my cousins called me gaijin.”

She has the good grace to wince. “Ouch.”

“Yeah.” I hunch over. I stare at the washi paper. Mountain was my latest attempt. But before that was sky, middle, and sun. I focus on the sun character—Japan’s national emblem. The first emperor, Jimmu, was born swaddled in golden rays. He descended from Amaterasu. How could you ever go wrong with the light at your back?

She makes a noise in the back of her throat. “Those girls. Their mother is around too little and their father gives them too much, as if material things will make up for her absence.”

“Please. Don’t make me feel bad for them.”

“I’m not. They’re terrible. Believe me. I’m not surprised they said something like that. They don’t attack unless they feel truly threatened.” I feel a smidgen better. She juts her chin at the washi paper. “I wouldn’t waste any time thinking about them. Focus on kanji instead.”

“Is this your idea of tough love?” I give her the side-eye. “Because you should know it’s my least favorite kind of love.”

Mariko doesn’t reply, only raises her eyebrows. At length, I set a new paper in front of me, dip the brush, and tap out the excess ink. I keep my hand light and patient and think only of the here and now. The line I’m making, and not the word. It only takes a second or two, but when I sit back, I grin. It’s a little wobbly at the top and too thick at the bottom. A little weak, but with a promise of strength. It definitely could be fine-tuned a bit. But I like it. It is an expression of my soul, after all—my messy, messy soul.

Mariko peruses my effort. “Still needs work, but better.”

I examine her, then brighten. “Oh my God! I just figured something out.”

She comes to attention. “What? What is it?”

My smile is sly. “You like me.”

“What?” She scowls. “I do not—”

“You like me,” I say with a firm nod.

“Stop saying that.”

“You like me and want to be my friend.”

“If anyone hears you, they’re going to think you’ve lost it.” Mariko’s lips purse. She crosses her arms and huffs out. “I respect that you are trying. It’s not easy. You’re rising to the challenge. It’s … admirable, I guess.”

“Uh-huh.” I give her a knowing look.

Mariko can’t even. Her sigh is long and drawn out, aggrieved. “Do you want help practicing your kanji or not?”

“Yes,” I say beaming, then sing, “friend.”

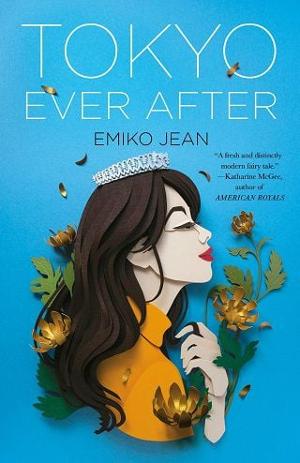

THE TOKYO TATTLER

The Lost Butterfly holidays in Kyoto

April 21, 2021

Despite fatigue cutting short His Imperial Majesty’s tour of Southeast Asia, preparations for his eighty-seventh birthday are well underway. All imperial family members will be present. A formal audience has been scheduled where Her Imperial Highness Princess Izumi will officially be introduced to her grandparents for the first time.

Recently, Tokyo Tattler correspondents and locals have spied HIH Princess Izumi out and about in Kyoto. Spottings have mostly occurred in the evenings (inset: Princess Izumi seen visiting a temple and geisha house last week).

While HIH Princess Izumi holidays in Kyoto, her twin cousins have been carrying the imperial workload, attending official duties on behalf of their mother, Her Imperial Highness Princess Midori, who hasn’t left imperial grounds in weeks.

And what of her second cousin, HIH Prince Yoshihito? Our palace insider said the two have grown close. In an exclusive scoop, HIH Prince Yoshihito was just seen boarding the imperial train. His destination? Kyoto.

Fullepub

Fullepub