Chapter 7

Grandpa Charlie

Earl Woods is more familiar than most with the realities of being a Black athlete in America, particularly in a traditionally white sport.

Twenty-year-old Earl played catcher on the Kansas State College baseball team, earning varsity letters in 1952 and 1953, making him not only K-State’s first Black baseball player but also the first-ever Black player in the entirety of what was then the Big Seven conference.

“My teammates treated me all right, it wasn’t their fault,” Earl recalls, “but I wasn’t afforded the same privileges as they were. For instance, I would not stay in the same hotels. We would go to the University of Oklahoma and the team stayed in Norman, where the University is, and I had to stay in Oklahoma City, an entirely different town. I had to get in a car in my uniform after the game and drive to Oklahoma City. There were no hotels that would take Blacks in Norman, Oklahoma.”

He was offered a contract with the Kansas City Monarchs to play in the Negro Leagues, but in 1953 the new college graduate instead joined the military, desegregated five years before by President Harry Truman’s Executive Order 9981. “The theory was that the army was integrated… Just like our society was integrated,” Earl says drily.

Of his first posting—as an officer at Fort Benning, in Columbus, Georgia—he remembers, “Four of us were walking down the street, two black, two white, just window shopping, enjoying ourselves,” he says, “and all of a sudden the police came up and threw us against the wall, handcuffed us, put us in the wagon and drove us to jail. We were fined for disturbing the peace—$32 and five cents,” equivalent to around $365 today. The charge? “Blacks and whites weren’t supposed to mix in public, that was our crime.”

Earl stayed in the military for twenty years. After he and Tida married, he posted to Fort Hamilton, in Brooklyn, New York, where in his early forties he discovered a late-blooming passion for golf, devouring books on the subject and playing round after round at the Dyker Beach Golf Course, in the shadow of the Verrazzano Bridge.

With the zeal of the convert to a new religion—golf—Earl began eagerly catching up on the groundbreaking success of Charlie Sifford, who in 1961 became the first Black golfer allowed to join the PGA. On January 12, 1969, forty-six-year-old Sifford had a momentous win at the Los Angeles Open at Rancho Park, the popular municipal course out Pico Boulevard past the 20th Century Fox movie lot. The city declared February 3, 1969, Charlie Sifford Day.

That night, Sifford spoke to a joyful crowd gathered in Los Angeles’s Black Fox nightclub: “It’s so wonderful to think that a black man can take a golf club and become so famous.”

Four days before the January 12 tournament, Pulitzer Prize–winning Los Angeles Times columnist Jim Murray devoted a column to Sifford’s achievements.

“Prior to Charlie, pro golfers had the effrontery to have a ‘Caucasians Only’ clause in their bylaws. It was the recreational arm of the Ku Klux Klan.

“Charlie birdied, not talked, his way through social prejudice. He broke barriers by breaking par. His weapon was a 9-iron, not a microphone. Charlie stands as a social pioneer not because he could play politics, but because he could play golf.”

Sifford learned the game as a North Carolina country-club caddie, served in a segregated US Army, and survived World War II combat in Okinawa.

In 1947, Jackie Robinson integrated professional sports by joining the Brooklyn Dodgers. Sifford asked the star hitter and fielder how he could do for the Professional Golfers’ Association of America what Robinson had done for Major League Baseball.

“I went to Jackie and told him what I wanted to do,” Sifford said. “He asked me if I was a quitter. I told him I wasn’t a quitter and he told me to go ahead and take the challenge.”

Though the five-foot-eight, 185-pound Sifford built a game strong and consistent enough to win six Negro Opens, it wasn’t until 1961, when he was thirty-eight, that Sifford (with an assist from the attorney general of California) finally earned a PGA Tour membership card. His Los Angeles Open win earned him $20,000 ($166,000 today) in prize money, national celebrity, and a mailbox filled with letters from Black kids who shared his dream. In 1975, Sifford also won the PGA Seniors’ Championship.

“I got one real thought about this,” Sifford says. “The Lord gave me some courage to stay in there when it got close. I don’t know whether I proved that the black man can play golf, but I proved that Charlie Sifford can.”

As Sifford tells Sports Illustrated not long after he wins the Los Angeles Open, “Golf has been the white man’s game forever, man, and the black man’s just comin’ to it now. Way behind. You know, you can’t play the game where they won’t let you play, and they didn’t let us play nowhere for a long time. It ain’t easy catchin’ up now. Not without money and without real good golf courses to play on and without goin’ to college to play golf there—you know any black golfers in college, man?—and without good instruction when we’re kids. But they did give us a chance to play golf now and it’s open for us if we really want to do it.”

Back in 1961, when Sifford was new to the professional tour, he traveled to North Carolina to play a tournament in his home state. White spectators verbally harassed him throughout the first round, and that evening an anonymous caller warned him against continuing the tournament.

“Whatever you’re going to do,” Sifford told the threatening caller, “you’d better be ready at 9:30. Because that’s when I’m going to be out there on the first tee.”

Through all the challenges, Sifford believed in himself, stating to Sports Illustrated, “I don’t want to be the best Negro golfer in the world, I want to be the best golfer—period.”

It’s the same response Tiger gives decades later. “I don’t want to be the best black golfer ever,” he tells everyone. “I want to be the best golfer ever.”

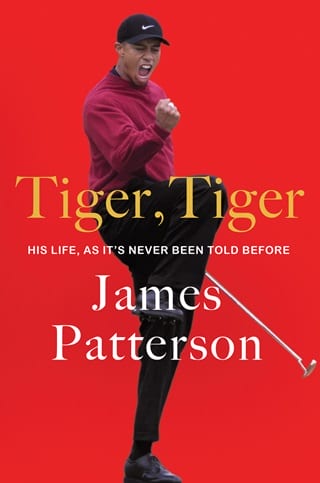

There’s an immediate connection when Sifford and Tiger meet.

“He’s like I was, determined to win,” says Sifford. “I chose him as my grandson. I treat Tiger that way. That’s how I feel about him.”

The feeling is mutual. Tiger refers to Sifford as Grandpa Charlie, despite there being only a decade’s age difference between Sifford and Earl.

Charlie Sifford is famous on and off the course for puffing cigars and telling golf stories, but at times the talk turns serious. “There is no way in hell he will have to deal with the hassles that I had,” says Sifford. “Man, the way has already been paved.” Which is not to say it will be an easy road for Tiger. “The thing is, he will still have opposition. And he will be out there all by himself.”

Sifford comes out to watch Tiger play a junior tournament in Texas. Tiger eases into the comfort of what Earl calls in his coaching SOP, or standard operating procedure, working the same preshot routine he’s had since he was six.

At one green, Tiger stalks a birdie putt. Earl turns his back to Tiger and begins a hushed play-by-play for Sifford: “He takes one practice stroke, he takes another. He looks at the target, he looks at the ball. He takes another look at the target, he looks at the ball.”

And when Earl says “impact” at the exact instant Tiger’s putter meets the ball, all Sifford can say is, “Goddamn.”

Fullepub

Fullepub