Chapter 35

Byron Nelson Golf Classic

TPC Four Seasons Resort

Irving, Texas

May 15–18, 1997

What’s the old saying? Winning never gets old?”

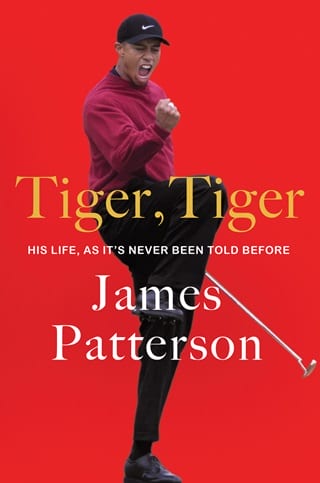

Tiger grins as he talks to the press while holding the winner’s trophy at the Byron Nelson Golf Classic in Texas. His fifth victory in sixteen tournaments as a pro comes a month after his record-setting win at the Masters.

The crowds have been so massive—one hundred thousand day badges and fifty thousand weekly passes—that Sports Illustrated casts around for a new way to label the phenomenon: “What started as Tigermania has evolved into something else. Tigerfrenzy? Tigerhysteria? How about Tigershock?”

“Wherever Tiger goes in the world, it’s like the Beatles have landed,” says his agent, Hughes Norton.

Tiger’s final score of 263, 17 under par, matches the record set by Ernie Els two years earlier, though it comes as no surprise to the eighty-five-year-old tournament namesake, Byron Nelson, a record-setting golfer in the 1940s with fifty-two career victories who once won eleven in a row.

Nelson’s had his eye on Tiger for years. “He was the best 15-year-old player I had ever seen,” he says. “He was the best at 16 and 17 and so on. He’s the best 21-year-old player anyone has ever seen. If he keeps getting better, oh boy. I’m not sure golf has seen anything like him before.”

“I keep telling you guys, this is just the start,” Tiger’s swing coach, Butch Harmon, says to reporters. “It’s going to get better, it’s going to get better.”

Still, there are a few hairline cracks showing. Harmon had been in Houston on Saturday when he spotted something off with Tiger’s swing on TV.

“He was backing up on his tee shots and flipping his hands through. He missed a few drives left,” Harmon says. He calls Tiger. “I see something in your driver swing. Get me a room in Dallas, and I’ll drive there tonight.”

Harmon travels the three and a half hours to show him in person.

“Thanks, Butchie. I got it. I appreciate you coming,” Tiger tells him after they work things out on the driving range the next morning. He’s feeling confident. “Don’t worry, I’ll win today,” he says.

He does.

“But what amazed me,” Harmon says, “was, from the first tee that day, he never made the mistake he was making the day before. He committed 100 percent to what we worked on that morning, and he drove the ball beautifully.”

What Harmon doesn’t know, however, is that a total overhaul is on the horizon.

Tiger Woods sits in a darkened room at the Golf Channel studios, wincing at the images on the TV monitor.

By any objective measure, Tiger’s on a historic roll. In June of 1997, shortly after his win in Texas, he takes the number one spot on the Official World Golf Ranking. Not only that, but it’s also been a mere 291 days since he became a professional—yet another record-setting achievement, this time for fastest ascent to number one.

And yet: something is bothering him. His swing feels out of sync. Tiger makes the short drive from Isleworth to Orlando to watch the tapes of his Masters win. Far from banishing his concerns, revisiting his most seemingly invincible performance does the opposite.

“I saw some of my swings on videotape and thought, God almighty, I won, but only because I had a great timing week. Anyone can do that. To play consistently from the positions my swing was in was going to be very difficult to do,” Tiger explains.

As he studies the video and freezes his swing at various points in its arc, he sees only flaws. At the top of his backswing, the clubface is closed and the shaft crosses the line, meaning that it points well right of the target. Distance control on his short irons is inconsistent, and overall his swing seems too handsy through the ball. Before leaving the room, Tiger makes a list of ten or twelve things that he wants to correct.

You know what? I know I can take it to a new level. Tear it down and build it back up, Tiger thinks.

When he calls his swing coach, Butch Harmon tries to assure Tiger that whatever flaws he thinks he’s found are minor. When it comes to golf swings, Harmon knows that the pursuit of perfection is dangerous. He’s seen too many golfers get lost on their quests for improvement and never find their way back. Look at your results, he urges Tiger. Let’s not go crazy.

But Tiger is talking about a significantly new and different swing: Less sidespin, less backspin. More control. Simpler. Tighter. Repeatable. A machine hardwired to make the same move again and again. A swing that won’t get stuck.

He wants a complete overhaul.

He’s looking to install a weaker grip.

Modify the takeaway.

Shorten and reshape the overall arc.

Adjust his hand position at the top.

The best golfer in the world wants to build a better golf swing. For an athlete at the very top of his game to revamp his fundamentals is unprecedented and borderline insane. Harmon keeps urging caution, one small adjustment at a time. Tiger keeps pushing back. We’ll do the whole menu now.

Harmon issues a warning. “It’s not going to be easy for you to make this change and still play through it.” A new swing is a little like an organ transplant—the body’s initial reaction is to reject it. Old positions ingrained by hundreds of thousands of repetitions have to be unlearned the same way.

But Tiger isn’t concerned. He’s twenty-one. He has all the time in the world. Plus, thanks to having just won the Masters, he’s got a ten-year tour exemption.

He’s not scared of change, not in the name of improvement.

“When I first changed my game drastically, I won three U.S. Juniors in a row, something no one else had ever done,” Tiger points out. Then, when he started working with Butch Harmon, he told him, I want a new game. “I knew I needed to improve. We tore down my swing, rebuilt it, and I won three U.S. Amateurs.”

The ideas and vision conceived in that darkened Orlando studio are Tiger’s and Tiger’s alone.

Fullepub

Fullepub