Chapter 29

Australian Open

Australian Golf Club

Sydney, Australia

November 21–24, 1996

The headline in the Los Angeles Times reads TIGER FOLLOWS THE CASH TO AUSTRALIA. The newspaper reports that Tiger’s contract for the Australian Open includes an appearance fee of $190,000, higher than native Australian Greg Norman’s rumored $158,000 appearance fee. The tournament, run jointly by the Australian Golf Union and IMG, will be Tiger’s first international event as a pro.

His agent, Hughes Norton, initially refuses to give any details, only telling the Associated Press, “I would say that something positive is going to happen.” Later, IMG distributes to journalists covering the Australian Open a glossy sheet filled with praise for Tiger from the world’s greatest golfers.

Gary Player, who came from South Africa to win nine major championships and build an unsurpassed international record, frames a generational progression: “The first time I saw Arnold Palmer, I said, ‘There’s a star.’ The first time I saw Jack Nicklaus, I said, ‘Superstar.’ I feel the same way about Tiger Woods. As long as he maintains his attitude, he’s got it. He’s a superstar on the horizon.”

On Thursday, November 21, a huge gallery turns out to see Tiger play his opening round. Under a cloudy sky, whipped by cold and wind, he shoots a disappointing 79.

Greg Norman shoots 67. The Australian, who’s won this tournament four times before, says charitably of Tiger, “At least he got the flavor of Australian courses. We play very difficult courses here. He got a shock when he shot 79. Perhaps he will appreciate why Australians play so well when they leave home.”

The next day’s temperature is the lowest Australia has ever recorded during November, typically the warm late spring season. Tiger comes down with another bad cold but does improve his score to 72.

A fifteen-year-old Australian named Adam Scott is in the field. Scott doesn’t make the cut, so instead of playing the final two rounds, he’s caddying for a friend—and working crowd control.

Scott is “so nervous” that he’s “probably looking at Tiger more than I was looking at a yardage book.” He’s on the 10th hole when he spots Tiger coming down the 18th, “dragging thousands around” in the packed gallery. “I’ve got a carry bag over my shoulders,” Scott says, as he waves both arms to “clear Tiger’s crowd for my buddy to hit a shot up the 10th green.”

Tiger shoots 79-72-71-70 and ends the tournament in a four-way tie for fifth place and a score of 292—twelve back from Greg Norman, who takes the top prize for the fifth time. But like a champ, Tiger does recover from that opening-round 79.

“He should find it easier next time,” Norman says, but there is one bright spot. “When the sun finally came out today,” Tiger says, “I thought I was back in America.”

Back in Orange County, California, Tiger takes a break from golf to spend Christmas Eve with his parents at the house he’s bought for them in Tustin. Not that they’ve gotten rid of the house in Cypress: Earl is convinced that Tiger’s childhood home will be considered a historical monument. “I am certain that one day the birthplace of Tiger Woods is going to become widely acknowledged,” he states.

Yesterday, the best gift imaginable hit newsstands nationwide: the December 23 issue of Sports Illustrated, with a full-bleed illustration of Tiger’s face on the cover, announcing him as its Sportsman of the Year. SI’s new top editor, Bill Colson, introduces the issue: “In case you blinked and missed it, golf is no longer your father’s sport… and Tiger Woods is SI’s 1996 Sportsman of the Year.

“At least for now.

“Just kidding.”

Sportsman of the Year is a serious achievement. Not only is Tiger the youngest athlete to ever get this honor, he’s also the first golfer to earn it since Jack Nicklaus did so in 1978, the year he won the triple career grand slam, having won all golf’s majors three times.

To Tiger, it’s important to keep the comparisons—and the expectations—in perspective. “People can say all kinds of things about me and Nicklaus and make me into whatever,” he says. “But it comes down to one thing: I’ve still got to hit the shot. Me. Alone. That’s what I must never forget.”

On December 30, 1996—his twenty-first birthday—it’s reported that he legally changes his first name. Eldrick is gone. Now there’s only Tiger.

He celebrates in Las Vegas, fulfilling a promise he made when he won the Las Vegas Invitational—returning to the host city now that he “can actually do some stuff around here.”

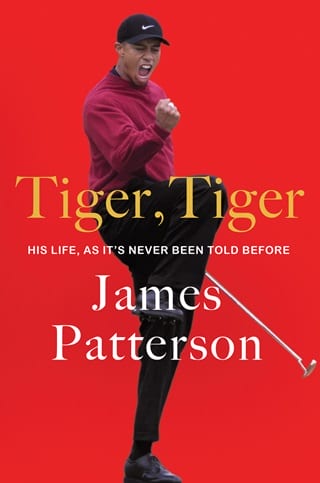

Nike chooses a solo image of Tiger—his face a mask of concentration, his torso coiled midswing—for its vintage-style, four-panel photo-strip-format holiday poster, tinted red and green and captioned “Happy New Year… of the Tiger.” According to the Chinese zodiac, 1997 will be the year of the ox (the year of the tiger will begin in 1998), but Tiger has his own way of making Nike’s prediction come true.

Now that Tiger’s twice made the cover of Sports Illustrated, national magazines are intensely competing to be next. Art Cooper, editor of GQ, hammers out terms agreeable to IMG, then leaves the logistics to the assistant managing editor, David Granger. “Most of the time when we wanted to put someone on the cover of GQ,” Granger says, “especially an athlete—they would give us the world.”

Instead, Granger gets around three hours: two hours round-trip between the new house in Tustin and Long Beach, where photographer Michael O’Neill will have another hour with Tiger in his studio.

Forty-three-year-old senior writer and sports columnist Charles P. Pierce gets the GQ assignment, in part because of his lifelong association with golf—his father was a high school golf coach at North High in Worcester, Massachusetts. “I play,” Pierce says. “Whether I like it is another matter.”

Before the January 13 interview, Pierce rereads “The Chosen One,” Gary Smith’s cover piece for SI’s Sportsman of the Year issue, and considers its central premise. “Tiger Woods was raised to believe that his destiny is not only to be the greatest golfer ever but also to change the world,” Smith writes in his opener, then asks: “Will the pressures of celebrity grind him down first?”

Pierce begins to form his own thesis, focusing on Earl’s boundless goals for his son. This is a pitch made on behalf of somebody who really is unformed, both as an athlete and as a celebrity, Pierce thinks.

The seasoned journalist sits in the back seat of the chauffeured limousine GQ sends to the Tustin house. Tiger steps inside the car.

Fullepub

Fullepub