Chapter 26

Texas Open

La Cantera Golf Club

San Antonio, Texas

October 10–13, 1996

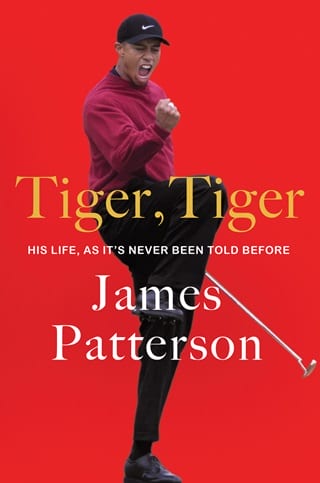

Ladies and gentlemen… direct from Las Vegas… where he won his first professional event last week… the three-time U.S. Amateur champion… from Orlando, Florida… Tiiiiiii-gerrrr Woods!”

The director of the Texas Open at the La Cantera Golf Club, in San Antonio, gives Tiger an introduction bursting with outsize Lone Star State hospitality, insisting to his staff that “Tiger Woods is not just a golfer, he’s a celebrity.”

“Direct from Vegas? I thought they were going to introduce Elvis,” joke the tour pros paired with Tiger, laughing almost too hard to tee off.

Tiger and Earl spend evenings with seventy-four-year-old Charlie Sifford, present as a special guest of the tournament. Today’s honor can’t erase the systemic racial discrimination Sifford’s faced here before, though, when in 1961, despite the PGA’s finally officially dropping its “Caucasian only” clause (one of the last American professional sports organizations to do so), Sifford still found himself physically barred from the course by pistol-wielding Texas Rangers.

Often called the Jackie Robinson of golf, Sifford is also often called surly and bitter. But he has good reason to mourn his missed opportunities. “I really would like to know how good I could have been with a fair chance,” he says of the hardships he endured. “I’m not angry at anybody, but I never will understand why they didn’t want the black man to play golf. Nobody ever loved this game more than me.”

“Without Charlie Sifford, there would have been no one to fight the system for the blacks that followed,” says Lee Elder, one of the first Black professional golfers to come up on the path Sifford forged, despite stiff opposition. “It took a special person to take the things that he took: the tournaments that barred him, the black cats in his bed, the hotels where he couldn’t stay, the country club grills where he couldn’t eat.”

Tennis legend Arthur Ashe, who faced similar barriers while playing a traditionally white sport, notes that “Sifford ultimately had only his homegrown survival instincts and family to sustain him.” But that was before Tiger Woods—whom Sifford lovingly calls Junior—burst onto the scene.

“Tiger is amazing—he makes me feel like all the hard work I did was worth it,” says Sifford. “I’m quite sure there’s a lot of young black kids who have picked up golf clubs since reading about Tiger.”

Tiger’s honored to have his cigar-chomping surrogate grandfather on hand for this long-dreamed-of moment: joining the PGA Tour as an official full-time member.

Tiger now possesses the ultimate tour status symbol: a personalized PGA money clip.

This heavy piece of metal—TIGER WOODS, 1996, his reads—is the equivalent of a player’s ID, allowing access to parking, dining, and range facilities, including the right to walk onto the first tee at each and every host course. It’s “pretty cool,” says Fred Couples, “to wear it on my belt.”

Also on offer: a wives’ badge.

“What am I going to do with that?” Tiger jokes with the PGA rules official. “Think about it,” he says. “Most of the women my age are in college.”

On tour, he has no time for a girlfriend, let alone a wife. He barely has time to even shop for clothes beyond whatever arrives in the boxes from Nike.

“You can’t wear Nike twenty-four hours a day,” Butch Harmon says, teasing Tiger as he guides him through making purchases at the mall in San Antonio.

The clerk ringing Tiger up announces that not one but two of his credit cards won’t go through. It’s not for lack of funds. But this is new territory for the twenty-year-old.

“Well, you activated them, didn’t you?” Harmon asks.

“What’s that?” Tiger answers.

“That just shows he’s a kid,” the swing coach realizes. He’s got a lot to learn about handling his newfound wealth. Especially since Tiger always seems to be short on cash. “For a rich guy, you sure are poor,” jokes his IMG agent, Hughes Norton, who often finds himself handing over the cash in his wallet to Tiger.

“What kind of a damn millionaire are you?” Tida grumbles at her son as she covers his expenses.

La Cantera Golf Club is the hometown course for thirty-eight-year-old Texas pro David Ogrin, who leverages his local knowledge into a final-round lead. Aiming for his first win in fourteen years on tour, Ogrin remains steadily confident, even when he triple-bogeys the 6th.

“I had no idea that he was making a run,” says Ogrin, who missed the news that Tiger had tightened the gap. But he’s been keeping an eye on the newcomer in general. “Anybody who was paying attention knew” that Tiger was something special. “And I was paying attention.”

The win and its $216,000 purse move Ogrin to number 32 on the money list, just two spots above Tiger, who moves to number 34 from number 40 after only six tournaments.

Two weeks ago, Tiger was hoping to make it to the top 125. Now he’s only four spots from the top thirty and qualifying for the $3 million TOUR Championship at Southern Hills Country Club, in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Maybe a little Disney magic will help get him there.

Fullepub

Fullepub