Chapter 16

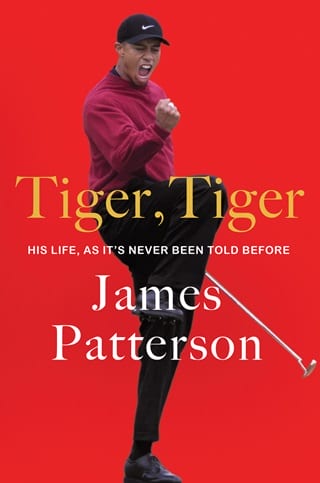

The 59th Masters

Augusta National Golf Club

Augusta, Georgia

April 6–9, 1995

Tiger’s Stanford roommate takes a message from “a guy named Greg with an Australian accent”—then forgets to mention the missed call until Tiger is packing his bags.

Greg Norman? Why would he be calling?

As the top two players at the 1994 U.S. Amateur, Tiger and Trip Kuehne have both won automatic bids to the 1995 Masters. They check into the Crow’s Nest, Augusta National’s dorm for amateur golfers. The friendly rivals laugh and play cards at night, taking practice rounds for bragging rights and five-dollar bets. But the Monday and Tuesday practice rounds feel more like auditions for the PGA Tour.

Five-time major championship winner Nick Faldo is surprised when Tiger outdrives him on the 15th hole. “His shoulders are impressively quick; that’s where he gets his power. He’s young, and he has great elasticity,” Faldo tells reporters on April 3. “He’s just a very talented kid; let’s leave it at that.”

On April 4, Tiger plays a round with three pros: Raymond Floyd, Fred Couples, and Greg Norman.

That’s why Norman was calling my dorm in Palo Alto—to arrange a tee time, Tiger realizes. The two of them also share a swing coach, Butch Harmon.

Out on the 2nd fairway, Tiger drives his ball farther than all three PGA champions in his foursome. According to Golf magazine, “Tiger’s already the longest player in the field.”

“My god, I had no idea how long he was,” says Tiger’s golf hero, Jack Nicklaus, as he watches the nineteen-year-old Stanford freshman play.

While he’s waiting for the others to catch up, Tiger chats to the gallery. “What a beautiful day,” he says. “You know, I could be in a classroom.”

An Augusta National marshal overhears and replies, “Yeah, but you would never be getting an education like this.”

Today’s lesson: “I really found out how good these guys are,” Tiger says.

“When he plays with the Couples, the Normans, the Faldos, the Prices,” Harmon says, “he marvels at the way they control the ball in the air.”

Greg Norman, a spokesman for Maxfli, suggests to Tiger that he switch from Stanford-issued Titleist golf balls to Maxfli.

Tiger scores an even-par 144 in the first two rounds and makes the cut. Earl tells the Washington Post, “We had an agreement between the two of us that he’d never play at the Masters until he earned his way in. I just didn’t expect it to happen this soon.”

He’ll be the lone amateur in the weekend’s field of forty-seven and only the fourth Black player ever to compete at the Masters. Earl wears a cap that reads DON’T HOLD BACK, but on questions of racial friction at the club, Tiger answers evenly, “I haven’t encountered any problems except for the speed of the greens.”

Friday morning, however, Earl and Tida discover an ugly reminder of Augusta’s past. One of the windows on their rental car has been smashed. Undeterred, the proud parents will continue walking alongside their son throughout the tournament, all seventy-two holes.

In the locker room, Tiger receives a telegram. “Go out there, good luck, don’t get caught up in the hype,” the message says. “Just take care of business and have fun.”

The words of encouragement are from Tiger’s surrogate grandfather, Charlie Sifford, the Black golfer who never had a chance to play the Masters. The first Black player who did—Lee Elder—is here watching, along with Black fans who’ve turned out in record numbers.

Near the first tee, Earl confides to Elder that he feels like he’s “witnessing my son coming into manhood. It’s a stage many fathers never get to see.”

At 1:03 p.m., the CBS Sports broadcaster announces, “Tiger Woods now driving.”

Tiger signs another round of autographs for the largely Black staff at Augusta National, then he and Earl drive off the club grounds to Forest Hills, the public course in Augusta, where caddies and golfers are gathered on Friday night for a free clinic.

San Francisco Chronicle columnist Scott Ostler explains the rarity of the event: “Almost 900 golfers have played in 59 Masters Tournaments, and only one of them has taken the time to give a clinic at that frumpy muni course.”

“It’s a Black thing,” Earl says, referring to the fact that until 1982, all the caddies who worked the Masters were Black. “We are acknowledging that we know who came before Tiger.”

Jerry Beard, who caddied Fuzzy Zoeller’s 1979 Masters victory, says of his fellow Black caddies, “We have been the forgotten men of the Masters, but maybe Tiger will help us be remembered.”

Earl carries a camcorder to document every moment of the week. Even with all eyes on Tiger, the tournament doesn’t belong solely to him.

Ben Crenshaw and Davis Love III are playing for Harvey Penick, their beloved coach and a bestselling author who died at age ninety on the eve of Masters Week. “I felt this hand on my shoulder, guiding me along,” Crenshaw—who paused his tournament preparations to serve as a pallbearer at Penick’s funeral in Austin, Texas—tells Sports Illustrated.

Crenshaw, the 1984 Masters champion, wins a second Green Jacket at 14 under par, with Love one stroke behind at 13 under.

Tiger finishes nineteen strokes back, tying for forty-first place. It’s a respectable showing for his first attempt, but Steve Burdick says what the Stanford teammates are thinking: “If that’s how Tiger stacks up against Tour players, we’re all in trouble.”

Still, Tiger is Low Amateur; his reward is a sterling silver cup and a coveted interview inside Butler Cabin, the 1964 landmark house where CBS Sports broadcasts its Masters interviews in front of a stone fireplace.

At Earl and Tida’s request, CBS’s Jim Nantz and the Augusta National vice chairman, Joe Ford, tape the interview so that Tiger can attend his Monday morning history class. “College is such a great atmosphere and I really love it there,” he says.

Back in the Crow’s Nest, Tiger looks up at the walls covered with photographs of Masters champions. “I feel like this place is perfect for me. I guess I need to get to know it better.” He makes a pledge—“Someday, I’m going to get my picture up there.”

He writes a letter to Augusta National:

Please accept my sincere thanks for providing me the opportunity to experience the most wonderful week of my life. It was fantasyland and Disney World wrapped into one. I was treated like a gentleman throughout my stay and I trust I responded in kind.

The Crow’s Nest will always remain in my heart and your magnificent golf course will provide a continuing challenge throughout my amateur and professional career.

I’ve accomplished much here and learned even more. Your tournament will always hold a special spot in my heart as the place where I made my first PGA cut and at a major yet! It is here that I left my youth behind and became a man.

For that I will be eternally in your debt. With warmest regards and deepest appreciation.

Sincerely,

Tiger Woods

The letter is not the only writing Tiger’s done this week. His Masters diaries are also published by Golf World and Golfweek magazines.

Although Tiger isn’t paid for the diaries, Stanford is quick to act, suspending him from the team for one day. The NCAA director of legislative services explains the decision: “It’s deemed to be a promotion of a commercial publication.”

Amateurs are also prohibited from accepting equipment from manufacturers, so Stanford has even more questions about why Tiger replaced his university-issued gear, using Butch Harmon’s Cobra irons instead of Mizuno irons and using Greg Norman’s Maxflis instead of Titleist balls.

The Maxfli balls are winners for Norman at the 1995 Memorial Tournament, held a few weeks later, in the first week of June. Norman bests his closest opponent by four strokes, but everyone at the Muirfield Village Golf Club, in Dublin, Ohio—the Jack Nicklaus–designed course near his hometown, Columbus—is talking about the amateur who isn’t eligible to play in this PGA Tour event.

No one has a better read on the Stanford student’s situation than Nicklaus.

In 1961, Nicklaus—then a twenty-one-year-old Ohio State University student and U.S. Amateur champion—asked to be excused from class. His professor complained to the dean, who told him, “Jack, I can’t have a student of ours going to Australia, playing golf when you’re enrolled here… I want you to drop out of school.”

Nicklaus did, though he was later awarded an honorary doctorate from the University of St Andrews, in 1984.

“Tiger has all the right tools to be a successful and dominant golfer,” Nicklaus tells Sports Illustrated at the Memorial. “He has a college career he wants to finish, but at the same time he’ll be receiving invitations to pro events all over the place. It’s up to him to determine how much he wants to focus on golf and what his goals are.”

Those details are private.

“My goals are my goals,” Tiger says. “Money won’t make me happy,” he says. “If I turned pro, I’d be giving up something I wanted to accomplish. And if I did turn pro, that would only put more pressure on me to play well, because I would have nothing to fall back on. I would rather spend four years here at Stanford and improve myself.”

Earl is characteristically blunt. “Tiger doesn’t need the NCAA and he doesn’t need Stanford. He could leave and be infinitely better off, except that he wants to go to school.”

Tiger sits for final exams. He has no plans for vacation. He’ll spend the summer playing against the pros.

Fullepub

Fullepub