Chapter 13

National Minority Collegiate Golf Championship

Manakiki Golf Course

Willoughby Hills, Ohio

May 15, 1994

There’s a spring chill in the Sunday morning air as a small group of junior golfers warms up at the driving range next to the first tee, surrounded by maple trees.

Tomorrow, the Manakiki Golf Course, a Cleveland Metroparks course named after a Native American word for “maple forest,” will host the National Minority Collegiate Golf Championship. Today, Tony Grossi, a Cleveland Plain Dealer reporter freelancing for Golfweek, is here to cover Earl and Tiger Woods’s pre-tournament juniors’ clinic.

Grossi’s attention is drawn to the range, where Earl Woods unfolds an aluminum stool and opens a suitcase-shaped device equipped with a set of speakers and a microphone. Grossi quickly gets the gist of this traveling road show: Earl directs; Tiger demonstrates.

“Tiger can hit three different shots with each club—left-to-right, right-to-left, and knockdown,” Earl says into the mike as Tiger works up a sweat showing the kids how it’s done. He cleanly executes a complex drill that has him aiming at a flag set 155 yards down the range. He hits that pin using four different clubs—an 8-iron, a 7-iron, a 6-iron, and a 5-iron.

The training session lasts an hour, during which Tiger never breaks concentration or speaks, though he’d previously joked to Grossi that “these players are older than I am.”

The golfers present aren’t especially starstruck by the three-time U.S. Junior Amateur champion, though at six foot one, the eighteen-year-old last-semester senior towers over the handful of students who ask for autographs. He’s still rail-thin, despite trying to gain weight. “I can eat anything I want and not gain a pound,” he laments to the Los Angeles Times. “I’ve eaten two steaks and two prime ribs at a meal. Nothing.”

Tiger and his dad have run many similar clinics, particularly for minority kids without much exposure to golf. After the U.S. Amateur in August of 1992, Tiger visited Seattle’s Fir State Golf Club, established in 1947, forty-five years earlier, by a group of twelve men and two women because the city’s other courses wouldn’t allow Black players.

“He’s cool,” said a nine-year-old, one of the thirty or so kids at Fir State who’d been mesmerized by the then sixteen-year-old. Tiger was happy to hear it.

“I tell kids golf is a very difficult sport, more difficult than basketball,” he said, knowing that especially among minority kids, basketball is the more popular game. “Maybe I’m the leader of a new generation of black golfers.”

Tiger’s partnered in these clinics a few times now with forty-five-year-old Jim Thorpe, currently the only Black golfer on the PGA Tour aside from thirty-one-year-old Vijay Singh, from Fiji.

“It’s a shame,” notes Thorpe. “When I first came on the Tour there were probably eight or 10 black players out here. Now I’m the only one left.” Thorpe, who grew up the son of a groundskeeper, understands that the barriers between these kids and the game go beyond interest and skill—there’s a lack of equipment and nowhere to play. It’s crucial, he feels, “to get kids to understand what the game can do for them.”

Tiger, Thorpe says approvingly, “is doing everything right.” In addition to having “one of the most beautiful golf swings I’ve seen,” he says, Tiger’s “got a great work ethic and as an amateur he’s already played a lot of the great courses. And he’s got his dad there with him.

“You look at all that, you figure he won’t stray too far.”

Teenage Tiger still struggles with how much importance to attach to his racial identity. At the clubhouse in Manakiki, he settles in with a candy bar and a drink of water as Earl steps outside for a cigarette and journalist Grossi asks Tiger his thoughts about being a role model, given tomorrow’s National Minority Collegiate Golf Championship. Does he feel a responsibility to open the game of golf to African Americans?

“That’s a funny question,” Tiger says, pointing to his mostly Asian background. “My mom is part Thai and part Chinese, and my father is actually part Chinese. So I’m actually one-fourth black. When I go to Thailand to visit or to play in tournaments, I’m considered a Thai role model, but over here I’m considered a black role model.”

Tiger prefers to take a broader view. “All that matters is I [reach] kids the way I can through these clinics and they benefit from them,” he says. “I have this talent. I might as well use it to benefit somebody.”

With Earl out of earshot, the reporter digs deeper, asking whether Tiger ever feels parental pressure or fears burnout.

Tiger denies both.

“I love this game to death,” he says. “It’s like a drug I have to have. I take time off sometimes because of the mental strain it puts on you, but when I’m competing, the will to win overcomes the physical and mental breakdowns.”

The Oregonian reports an unusual development: “Eldrick ‘Tiger’ Woods conquered all the worlds of junior golf, and then he did a curious thing. He changed his swing.”

The new swing is designed to produce accuracy, consistency, and control, the cornerstones of a swing built to repeat, the goal of any great golfer.

“Butchie harped at me to understand how to hit the ball pin-high,” Tiger says of his swing coach, Butch Harmon, whom he’s only met in person twice. They mainly exchange videotapes and communicate by fax. “That didn’t mean flag-high. Pin-high meant whatever you decided was your number, not necessarily where the flag was. If the flag was 164 yards, maybe I’d want to make sure my ball carried 160 yards to keep it short of the hole and leave myself an uphill putt.”

It’s also a means to achieving a private goal. Jack Nicklaus was nineteen when he won the U.S. Amateur as a junior at Ohio State University. Eighteen-year-old Tiger wants to win that title before he’s even registered for his first semester at Stanford.

First stop on that goal is making it to the U.S. Amateur qualifier in Chino Hills, California. Though it’s less than an hour away from where the Woodses live in Cypress, Tiger and Earl aren’t at home—they’re coming from Michigan, where Tiger has just won the Western Amateur.

After missing their plane out of Chicago, they’re put on standby for the last possible flight that would allow Tiger to make his tee time.

Earl prays.

The airline gives the two passengers named Woods the last two seats.

“My prayers were answered,” Earl says. “Thank God we got on that damn airplane.”

Tim Finchem, a former aide to President Jimmy Carter, is in his first summer as PGA Tour commissioner.

It’s August 28, 1994, the final day of the World Series of Golf. Finchem presents the trophy to the winner, José María Olazábal, the Spanish national who in April had won his first Masters, then dashes off to investigate an incident: John Daly and the father of another player escalated an etiquette dispute into a wrestling match outside the clubhouse.

The Arkansas pro is famous for being the tour’s longest hitter—and for his competitive streak. “I can’t let this thirteen-year-old beat me,” Daly said of Tiger back in 1989, when the two played an exhibition at Texarkana Country Club. Daly won, but only by two strokes, admitting that Tiger was even “better than I heard.”

Now, five years later, Finchem walks into the locker room at the Firestone Country Club to find a group of pros riveted to the television. They’re watching the national broadcast of the U.S. Amateur Championship at the Players Stadium Course at TPC Sawgrass, in Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida.

Tiger is in the final, facing off in a thirty-six-hole match against Texas native Trip Kuehne, an all-American golfer for Oklahoma State.

Finchem is astonished. I’ve never seen tour players interested in watching any other golf on a day they were finishing a tournament. It is amazing to me that this kid generates that level of focus.

TPC Sawgrass is a stadium course designed by architect Pete Dye to maximize the fan experience. As the final opens, Kuehne dominates, ending the morning round 4 up. He overhears Tiger conferring with his caddie and sports psychologist, Jay Brunza. “Trip’s playing really good. He’s killing me. I don’t know how I’m going to beat him.”

Tiger also telephones his coach, Butch Harmon, who’s watching the tournament from California, for advice.

It’s Earl who’s struck by inspiration. He whispers in Tiger’s ear.

“Son,” he says, “let the legend grow.”

The words intensify Tiger’s motivation. Throughout the afternoon round, the wind picks up, blowing through TPC Sawgrass’s hundreds of trees, strategically placed to get in players’ lines of sight. Kuehne wins the 2nd and the 6th, but the momentum shifts with the wind, and on the 16th, Tiger pulls even.

At home in Cypress, Tida is watching on TV from her bedroom as Tiger reaches the notoriously difficult par-three 17th, with its legendary island green. Tiger’s tee shot hits the green—dangerously near the water’s edge.

God, don’t let that ball go in the water, Tida prays over and over. Don’t let that ball go in the water. If he bogeys the hole, or worse, the U.S. Amateur title belongs to Kuehne.

Under pressure with his club selection, Tiger had wavered. He’d picked up his 9-iron, then changed his mind. A pitching wedge would be better.

The pin. I was going directly at the pin.

“You don’t see pros trying to hit it right at that pin,” Kuehne says.

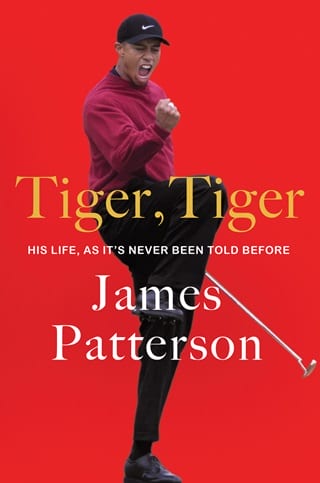

That is exactly what Tiger does before sinking a fourteen-foot putt to birdie the hole. He then unleashes an adrenaline-fueled fist pump, having erased Kuehne’s 6 up lead. He’ll go on to par 18 and win 2 up.

At home in California, Tida rolls off her bed and falls to the floor in amazement. “That boy almost gave me a heart attack,” she says. “That boy tried to kill me.”

On the course, Earl and Tiger, the first Black player to ever win the U.S. Amateur, embrace for several minutes.

Earl says, “This is ungodly in its ramifications.”

Fullepub

Fullepub