Chapter One

D orcas Anderson hoisted the strap of the heavy bag of linens and embroidery thread a little higher on her shoulder. Short as she was, it was hard to keep the bag from brushing the ground. That would be bad enough on any day, but worse when three days of heavy rain had turned the streets into a swamp of mud, dirty water, and other far more noxious substances.

Mr. McMillan, the man who employed her to apply family crests, monograms, or whatever motif buyers desired onto the household linens he supplied, would dock the price of damaged linens from her wages. Moreover, he'd refuse to pay for any work she had done on them. She'd delayed her visit during the rain and this morning, as soon as the sun had peeped through the clouds, she had gone to the drapery warehouse to drop off her finished work and to collect a new batch of linen rectangles and squares to embroider.

Now, she was walking home, keeping one wary eye on the gathering clouds. Even if she had had the coins to spare, she was unwilling to risk any table linens in the filthy interior of a hackney.

She carried two weeks' worth or more of work and therefore a month's rent, and food on the table for at least part of that month. The loss of even a set of table napkins could leave her hungry. More might leave her and Stephen destitute. Scraping the bag in the mud would be a catastrophe. Rain before she reached her room would be a disaster.

She readjusted the strap for the umpteenth time and trudged on.

The disaster she was trying so hard to avoid came looking for her just as she rested for a moment against a stone bench set a little back from the footpath. She had her back against the bench and the precious bag clasped to her belly as she looked idly at the passersby and wished she did not have so far to walk.

People must have rushed out to enjoy the brief sunshine, for both road and footpath were crowded. One lady caught her eye. She was clad in deep black, and a veil fell from her bonnet to cover her face. Dorcas found herself wondering about the widow. Did the heavy mourning represent the truth or a social lie?

Dorcas had worn black for Ves, and then again for Noah. Not, however, in the way the lady she now observed wore black. She smiled at the very idea. It was like comparing a sparrow and a peacock—her in her hastily-dyed everyday gowns versus the clearly wealthy lady who was picking her way cautiously around a puddle in her expensive and fashionable silks and velvets.

The lady was just walking past Dorcas when someone dashed out from the shadows and pushed her, so she stumbled into the street, right into the path of an approaching carriage.

Dorcas was barely aware of the assailant running away and was not conscious at all of casting her bag down and hurling herself after the lady. She didn't think, but grabbed a double handful of the lady's redingote and swung her around, just before the horses, snorting and stamping, reached their position.

For one horrid moment, she lost her own balance as the carriage raced toward her. She had a moment of piercing fear for Stephen and then strong hands grabbed her, pulling her to safety. And the lady in black, too, she noticed as a tall man with hard eyes set her on her feet, and another did the same for the widow. The carriage had driven on by, the driver hurling imprecations over his shoulder.

"How can I ever repay you?" The widow held her hands out to Dorcas. "You saved me from serious injury, at the very least. Titan, did you see who pushed me?"

"No, Mrs. Dove-Lyon," said the man who had caught the lady. "I've sent a man after him, but he was fast on his feet."

"And you, Miss?" Mrs. Dove-Lyon asked Dorcas.

"Missus," Dorcas commented. "And no, all I saw was his back as he gave you a shove."

"Mrs…?" Mrs. Dove-Lyon asked.

It was at that moment Dorcas remembered her bag. "Anderson," she replied absentmindedly, as she looked around. Her heart quailed when she saw her precious fortnight's income lying on the edge of a puddle. "My linens!" she moaned.

Sure enough, when she picked up the bag, she could see that one corner was completely saturated in muddy water.

"They can be washed," said Mrs. Dove-Lyon, who had followed Dorcas and was leaning forward to examine the problem.

"If there is the least stain, Mr. McMillan will take the cost of the linen off my wages," Dorcas explained. "They are table linens, you see. I embroider them for McMillan Bresset and Coletwistle, the drapery merchants."

Mrs. Dove-Lyon nodded, decisively. "I have a laundry person who is able to perform magic," she announced. "Titan, see that the bag comes with us. Mrs. Anderson, come with me. Whatever is wrong, we shall fix it. Ah. Here is my carriage. Come along, my dear."

Dorcas took a step backward. "I should be getting home," she said. The next-door neighbor would watch Stephen until Dorcas returned, but the extra pennies she would charge for the extra time would have to come out of the rent jar. "I must."

However, one of Mrs. Dove-Lyon's tall strong men had her bag. The man Mrs. Dove-Lyon addressed as Titan had finished helping the widow into the carriage and was now offering her a hand.

She hesitated a moment longer, but she could see through the carriage to the other door, which opened. The man with the bag put it into the carriage. Dorcas could not be parted from it, and perhaps, after all, the damage was not too bad.

A visit to the country was meant to be refreshing. Not so for Benjamin Barclay, Earl of Somerford. He had spent four weeks in the village of Findlater with his sister and her new family—the Earl of Buckley, her cousin-in-law, Viscount Findlater, her husband, and Richard Benjamin Warrington, their newborn son.

It had been wonderful, but it had left him dissatisfied with his life.

He loved Laurel, his sister. He liked Angel, her besotted husband. He liked Bertram, as Buckley had insisted on being called. He would even admit, in the secret recesses of his mind, to being thoroughly in love with little Richard. The tiny creature might do little but sleep and weep, but he had already cast his spell over the entire household and Ben was no exception.

Nor was their hospitality lacking. Indeed, Ben had thoroughly enjoyed his stay and had left for London with considerable reluctance.

What Ben had not expected was to arrive back in London and find the life that formerly satisfied him had suddenly become inadequate. He wanted what Laurel and Angel had. A loving spouse. Children. The rewards of the peace he and others had given so much to achieve.

Ben fought envy. He had spent three years in the country at his family seat and at the two lesser estates, learning about farming, rebuilding connections that had been severed by the arrogance of his father and his older brother, and trying to turn around his predecessors' ruinous practices.

Unlike Angel, he hadn't had a benevolent older cousin to teach him the ropes and introduce him to the locals. A cousin who had been granted the title when Angel was believed to be dead, and whom Angel would now succeed as earl. A cousin who had made wise financial choices. Ben didn't have a wife to run his households and take over leadership of the all-important distaff side of the local community and of London Society. Nor did he have a child to ensure the future of his much-diminished line.

Angel deserved his good fortune, and Ben didn't begrudge him any of his current happiness. Ben's brother-in-law had been little more than a boy when he was orphaned in a pirate attack, rescued by the British, and welcomed into the British army.

The poor man's contribution to the war had ended when a bridge he was preparing to blow up collapsed early, trapping his feet. His capture by the French had made his injury worse, and he'd spent years getting himself back on his feet—or at least on a pair of crutches.

Angel was now walking with a pair of canes rather than crutches, and even managing short distances unassisted. The doctor Laurel had found was apparently a huge help, having prescribed massage and specific exercises to strengthen the muscles in the damaged feet.

Both Laurel and Angel had thrown themselves into the local community, with Bertram's enthusiastic support.

Ben wanted what they had, which meant he had to find a wife. He could manage to find a bride with little trouble. He had a title and all his teeth. The earldom was solvent. All he had to do was appear at a Society event or two, and he would be mobbed by marriageable women and their matchmaking mothers.

The mere thought of it threatened to bring him out in hives. He'd far rather face a charge by the Imperial Guard. At least he understood how to fight back on that particular battlefield.

Invitations had been building up on his desk. He poured himself a brandy as fortification and sat to go through them.

Within fifteen minutes, they were sorted into three piles. The easiest was the collection for events that had been delivered while he was away and had already taken place. He made several tries at restacking the remaining invitations into a reject and a keep pile.

He tried to arrange them by type of event, rejecting routs and musicales and other such insults to the sanity of a retired soldier. Another attempt had him sorting them by hostess, with those he liked best or least wished to insult going into the keep pile. And then, he tried by the likelihood that the event would be attended by eligible ladies with a modicum of intelligence—but that was the least successful classification, for he knew too little about fashionable ladies to make an educated guess.

In the end, he stacked them in date and time order. He picked his preferred event when times clashed, and then pruned the remaining pile by ruthlessly discarding anything on an evening when Parliament was sitting. It was not that he attended every session, but even the most pompous of hostesses could not object to him putting the government of the realm ahead of her social event. Could she?

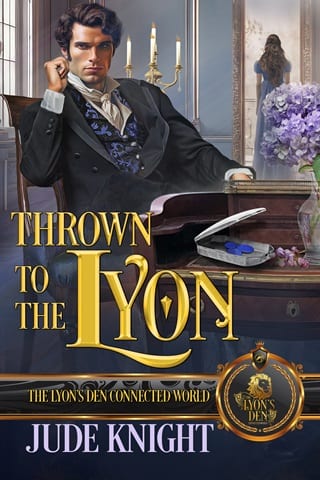

It crossed his mind, not for the first time, that Angel had taken a much simpler path to marriage. So had Sir Lancelot Versey, the Marquis of Wickes, and several other men that Angel knew. They had approached the proprietor of the Lyon's Den, one of London's most celebrated gambling establishments, who offered a sideline in brokering marriages. Rather like a matchmaker, though usually a wager of some kind was involved; Mrs. Dove-Lyon—the Black Widow of Whitehall as she was known—wasn't known to make matches out of the kindness of her heart. The matches at the Lyon's Den usually came down to some sort of a game of chance or skill.

Rumor had it that Mrs. Dove-Lyon stacked the games in favor of her preferred candidate. It was true that most of the ladies who sought her services had some flaw that diminished their value in the marriage market. Ben had to admit, however, that those whom he had met were all fine women, and very much in love with the husbands who had won the right to wed them.

His own sister had a reputation that was tarnished, in some circles, because she had jilted her betrothed. No one who knew the situation and the people involved could blame Laurel, but ton gossip was cruel and mindless.

Perhaps he should just ask Mrs. Dove-Lyon to find him a wife. The idea did not sit well with him, though. For one thing, he wanted his wife to be his choice. Ben did not like the idea of his bride being won on the turn of a card, or some other such game.

Also, the public nature of most of the matches made him uncomfortable. The ladies, to be sure, usually remained anonymous at the time of the marriage but what use was that anonymity when the new bride stepped out in Society with the groom who had last been seen climbing ropes or downing emetics or shooting the corner off playing cards to win a wife?

No, he would seek his bride the traditional way, at London entertainments and events, and retreat to the Lyon's Den only for a quiet drink and perhaps a game of cards with friends, away from the relentless pressure of the marriage mart. He was not much of a gambler—he never made bets he could not easily cover even now he had his estates in order—but he did take pleasure in a friendly game.

Fullepub

Fullepub