Chapter One

one

OUT OF THE CORNER OF Jemma Barker's eye, the woman flickered, a shadow of light shimmering at the edges of her vision.

Don't look at 'em, Jemma. That was Mama's voice.

Ain't nothing but the devil's work if you look. And that was Daddy's.

Taking a slow breath ( five, four, three, two, and one on the exhale), shakier than usual due to the train's rattling, Jemma stared into her light-wool-skirted lap, where twisting fingers worked wrinkles into a white handkerchief. When she glanced over at the empty seat next to her, the woman was gone.

Jemma smoothed the handkerchief, then her already smooth skirt, then her bobbed hair, the hot-combed bangs fluffing in the Southern heat, humidity intent on disarray. The man who'd sat in that seat, who'd boarded with her when she'd left Chicago two days ago, had gotten off somewhere in southern Missouri, right when one of the white-jacketed porters had hung a colored sign in their car. The sign wasn't necessary, as only Black passengers inhabited the car anyway. No white folks would sit in this space, without a luggage rack but with a flattened mouse in one corner.

No one—no living person, anyhow—had sat in the seat since.

The car had steadily emptied as they traveled south. Jemma opened her black patent leather handbag and pulled out an envelope. She'd read the letter inside dozens of times, but she wanted to see it again, to make sure it was real. It was dated less than a week after Marilyn Monroe had died, and even now, the papers were still making much of the actress's death.

The letter read:

August 10, 1962

Dear Miss Jemma Barker,

I am writing to offer you a position with the Duchon family in New Orleans, Louisiana. The Duchons are a prominent family in the city and believe you have the qualities we are seeking. You would have free room and board and be expected to live on the property. The pay is $300 per week. This is nonnegotiable. You must call by August 31 should you wish to accept.

Sincerely,

Honorine Duchon

Of all the details in the letter, Jemma stared at the three-hundred-dollar weekly pay the most. It was more than three times what she'd earned as a teacher in Chicago, before everything had fallen apart. So she had called Honorine Duchon one afternoon in mid-August, a few weeks ago.

"Next stop, New Orleans. New Orleans, next stop!" a porter announced, strolling down the wood-floor aisles. He stopped next to a dozing woman and touched her shoulder, making sure she woke up in time. She, like Jemma, had a single square suitcase between her feet. Jemma put the letter away and smoothed her hair again before slipping white gloves onto her hands and a pillbox hat onto her head.

Half an hour later, she joined a line of passengers who shared her color, disembarking after the white ones had already gotten off. Jemma stood for a minute on the concrete, purse in one hand, suitcase hanging from the other, the clean, modern lines of the Union Passenger Terminal looming ahead of her.

The heat was a womb. She'd thought summers in Chicago were bad, but nothing had prepared her for this.

A white man in stovepipe slacks and a fedora jostled her as he hurried past, and then he turned back, perhaps to excuse himself. The beginnings of a frown set between Jemma's brows, and chiding words formed behind her lips. Before she could say anything, however, his expression upon seeing a lone Black woman in last season's jacket and skirt, the indifference that dulled his eyes, reminded her that she wasn't in Chicago. She remembered the colored sign hanging in the train car as she pressed her lips together, watching the man continue to his destination, the encounter probably already seeping from his mind even as it brought a flush to her burning skin. The man's hurriedness was familiar to her, something that, along with his rudeness, reminded her of home. But when she took in the rest of the place, she was reminded of the differentness.

Early September in Chicago was a wave of cool weather, wool jackets and scarves at the ready. It was unpacking heavy sweaters, thermals and mittens. Gray skies and biting winds settled in for a long haul, and the taste of snow was always in the air.

So Jemma's attire was completely out of place. Women of all colors swirled around in silks and linens (linens!), cottons and organdies. The tones were suitable for fall—light gray, sky blue, deep pink, cream—but she was the only one in navy blue anything. And very few of the women she saw were wearing gloves. Moisture sprouted in her armpits, and not only from the heat. She removed her gloves and tucked them into her purse.

"Get you a cab, miss?"

Jemma looked to her right, where a porter smiled at her.

"No, thank you," she said. "But can you tell me where I can get some coffee?"

"Best for you to bypass the French Quarter. They're still boycotting over there on Canal, and you don't want to get mixed up in that. Make your way to this neighborhood called Tremé. You can catch the bus over there."

"Boycotting?"

He cocked his head. "Yeah. They don't want to hire none of us to work on Dryades 'less we're sweeping out the back room or scrubbing the toilets. We can't eat nowhere on Canal. So it's been some sit-ins and little marches and things."

A smile tugged at Jemma's lips. Although not immune to the oftentimes inexplicable whims of white people in Chicago who didn't want Black people to experience full citizenhood, she'd had more freedom there than the folks who lived across the South. And they were fighting back. Good.

"Can you give me directions to Tremé if I'm walking?"

"It'll take you a minute."

"I got time."

He gave her careful directions. Jemma pressed her handkerchief, now bearing blotches of brown powder, to her face and thanked him as she set off, the handle of the suitcase slick in her hand. Rivers of sweat ran freely down her body, and her legs itched in the thick stockings. Cobblestone streets stretched in every direction. There were no skyscrapers or tall housing-project buildings here, only walls of balconied structures and wrought iron railings. Jemma passed yellow, blue and pink stone buildings, with ivy and flowers trailing down from second floors or growing up brick sides like delicate fingers. The smells of soft bread, strong coffee, sweet pastries and thick roux filled the air, a jumble of scents that pulled Jemma's tongue between her lips. She'd eaten nothing since lunch the day before, the last of the roast beef sandwiches she'd packed, as there were no colored dining cars or other places where they were allowed to eat once they'd reached Tennessee. Glancing through the restaurant windows, she saw only white patrons.

As she navigated her way north, the smell of the Mississippi River gradually faded, although not completely. Colorful buildings and storefronts gave way to row houses. On Rampart Street, she turned down an alleyway, her feet in the black heels seeming to grow blisters against the cobblestones with every step. Jemma stopped and leaned against the brick wall between two nondescript buildings, setting her suitcase down and mopping her face again. All her powder had been wiped clean off, the remnants of her carefully made-up face soiling the handkerchief. She glanced around, now sure she was in the wrong alleyway. The porter had told her of a café down a specific backstreet but had also cautioned her, Stay away from dark alleys where you don't see nobody else . She'd wanted to remind him that it was morning, but something in his face kept the words inside. As she slipped one foot out of her shoe and rubbed her toes, a door in the building in front of her opened. Jemma tensed at the sight of the light man in a chef's apron until she took in the crinkled hair, the almost imperceptible wideness in his nose.

"You lost?" he asked her after tossing dirty dishwater out of a huge pot into a nearby grate. Hazel eyes appraised her, lingering over her heavy clothing before coming back to her face.

"I'm looking for Lulu's Café."

"Next alleyway over," he said, jerking his chin to the right. "There's no sign, but you'll see a window with some dolls inside."

Jemma had wanted to rest for a few minutes, maybe even cool off before moving on, but she felt like an intruder here, where the man now pulled a rolled cigarette from his apron pocket and lit it with a match. He didn't offer her one. Clouds of smoke obscured his face, but she felt his eyes on her.

She put her shoe back on, hitched up her suitcase and moved on to the next alley, finding the bright blue–painted café by the collection of brown-skinned dolls sitting inside the window, just as the cook had said. Jemma passed two yellow wrought iron table-and-chair sets as she walked inside, the coolness of the dim space so welcoming she shut her eyes, wanting only to breathe it in for a while. Ceiling fans turned overhead, spreading delicious smells around the room, all hot coffee, pralines, beignets and roux.

"Ooh, baby, I know you burning up." A woman's voice brought Jemma back. She found herself looking into the deep brown face and eyes of a middle-aged woman in a light blue dress and with a white apron around her waist. "Come on in here and sit down."

Jemma happily obeyed, taking a spot in a stiff-backed chair by the window. The table was small, made for two, and as Jemma took in her surroundings, she spied nothing but Black patrons at half a dozen tables, hunched over white cups of coffee or plates of bread and sausage.

"You want some chicory, honey?"

"I'm sorry—what?"

The woman smiled down at her. "It's a coffee. I'll get you one."

Before Jemma could protest, the woman walked off and disappeared through a set of swinging doors that led to the kitchen. Jemma opened her handbag and pulled out her coin purse, the peeling red leather petal-soft beneath her fingers. Snapping it open, she made sure she still had five wrinkled singles, along with a small handful of change. A chalkboard hanging on one wall advertised everything from chicory café au lait, pain perdu, beignets, croissants and calas to gumbo, crawfish etouffee, red beans and rice and croque monsieur. Jemma didn't recognize all the words, but the mix of sweet and spicy smells floating through the air reminded her how hungry she was.

"This is on the house." The woman, her head tilted as she looked down at her, slid a cup of coffee in front of Jemma. "Are you visiting?"

"No. I just moved here. I'm working for the Duchon family." Jemma pronounced it Du-chun , emphasis on the first syllable, unable to keep the breathy pride out of her voice. The woman stared at her for a moment before a look of recognition washed over her face.

"Oh, the Doo- chone family," she enunciated, the soft smile shrinking away. Her back straightened, all the friendly intimacy of their conversation disappearing along with the grandmotherly tone. "You want something to eat?"

Jemma's mouth worked (What just happened here?) , but after a moment, she asked for grits and eggs, knowing the breakfast cost just forty cents. She sipped her coffee, and before long, the woman returned, sliding a plate loaded with grits, eggs and toast onto the table. Alongside it, she placed a small plate with a couple of sugary confections.

"Oh, I didn't ask for—" Jemma started.

"It's on me, baby. You're new to New Orleans. You got to try Lulu's beignets." She turned to go but stopped and looked at Jemma again, the softness back in her eyes. "You're working for the Duchons, you say?"

"Yes. I was going to ask how to get to the…plantation." That's what Honorine had called the property when Jemma had talked to her a few weeks ago.

"It's not in the parish proper—it's out toward Metairie. You can take the bus, but it's going to let you off before you get there. Cab'll take you straight through, but it'll cost."

"I can take the bus. If I have to walk a ways, that's okay."

Lulu glanced away for a second before turning back, her deep brown eyes full of something disquieting Jemma couldn't quite place.

"Miss, it's not my business, but if I was you, I'd go the other way. Get back on the train or bus or whatever you came here on and go back to where you from."

"I…I have a job with the Duchons. They hired me to be a…tutor."

"Like I said, it's not my business." She left Jemma to eat in peace.

She had been so hungry, but what Lulu said dampened her appetite. Still, she had a bus ride and a walk ahead of her, so Jemma ate. The food was delicious, especially the sweet and flaky beignets, their powdered-sugar coating drifting down on the plate and her lap.

Afterward, Jemma found the bus she needed and settled herself in the back. White passengers filled the front, and a couple of Black men stood when Jemma and another woman boarded. The woman sat next to her, looking very cool in a striped dress, the skirt full and belted, her hair short and teased high at the crown, bangs swept to one side. Despite the heat, Jemma had put her gloves back on. She tugged the cuff over her right wrist, hiding the scar beneath, the skin raised and riverlike, evidence of an unsure hand. Hot air and dust blew in through the open windows, and with each hard stop Jemma's feet tightened on the sides of the suitcase so that it wouldn't slide away.

Just before noon, she disembarked at the last stop, a two-mile trek ahead of her, according to her seatmate on the bus. Jemma's feet ached, her body felt wrung out and the breakfast she'd eaten had shriveled into a hard knot in her stomach. If she'd had the money, she would've taken a cab then and there. She folded her jacket and placed it inside her suitcase, wiping her forehead with the back of her ungloved hand. Although there was no breeze, just having her arms out in the short-sleeved blouse was a relief.

She'd walked about a quarter mile when she heard someone call behind her. She turned to see a brown-skinned man driving a one-horse wagon, the wooden bed filled with hay.

"You need a lift?" he asked.

Jemma quickly dismissed her disorientation at seeing a horse-drawn wagon in this day and age, reminding herself once again that she'd left a big city far behind.

"I'm going to the Duchon plantation. Is that on your way?"

"It is." Something in the careful way he said it made Jemma think of Lulu back at the café. "Swing that case in the back. I'll help you up."

The man's name was Charlie, he told her, as she nestled on the bench seat next to him. The sleeves of his dress shirt were rolled up his arms, suspenders hanging off, sweat stains bleeding through the T-shirt he wore underneath. His planter's hat was pushed back on his head. Once he'd made sure Jemma was settled, he snapped the reins, and the bay horse moved its slow way down the dirt road.

"What you walking to the Duchons' for?"

"The bus line stopped back there. It's only a couple miles."

"More like almost four." His sidelong glance raked over her in seconds. "You woulda melted out here before you made it."

"I'm extra thankful for the ride, then."

They passed patchy woods and a long stretch of pasture, as well as the occasional towering oak tree, Spanish moss trailing from branches and brushing the ground like spiderwebs, the shade they cast a welcome gift. At Charlie's prompting, Jemma had told him she was from Chicago and was here to work for the family.

"A tutor? For who?"

Jemma almost said she would be a tutor for their child, but no one had actually told her whom she'd be tutoring. In fact, no one had said she was hired to be a tutor.

Ever since she'd gotten the letter, she'd assumed the Duchons knew she'd taught fourth grade, further assuming they must have a child around that age. When she'd called Honorine to accept the position, she hadn't asked many questions. The money had dazzled her. She'd been scared that if she asked too much, the woman with the clipped voice would change her mind about her, renege on the offer.

"Their child," she answered now, frowning.

Charlie looked at her for a brief moment. "Well, maybe something's changed out there."

"Do you know the family well?"

"No. They keep to themselves."

He didn't seem to want to talk much after that. He leaned forward, and something in the way he hitched his shoulders and whistled under his breath shut Jemma out.

A cream-colored Buick Roadmaster swerved around them, white-walled tires spinning up dust that hung in its wake. After a while, she concentrated on the dirt lane and the wooden fence running alongside it. Her world became the dappled light poking through the trees, and the horse in front of her, the soft clop of its hooves and its animal scent pushing the ghost woman on the train out of Jemma's mind.

"This is as far as I go," Charlie said.

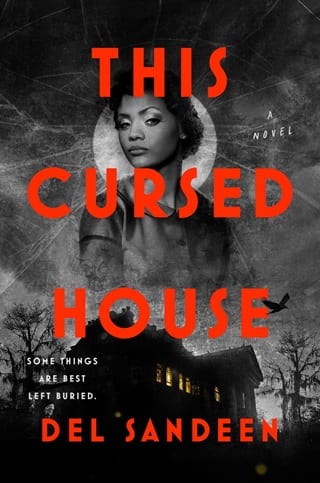

They were stopped in front of a wrought iron gate, a huge expanse of lawn behind it. Well behind the gate was a white antebellum house, four pillars standing tall across the front, straight like soldiers. Black shutters framed the large windows, two on either side of the black doors on the first floor, and six spanning the second. A wide porch ran along the first floor, enclosed by a white railing. Oak trees lined the pathway up to the house, and more trees hugged the building, keeping it in shade.

Jemma climbed down and retrieved her suitcase. She opened her handbag, but before she could pull out her coin purse or thank Charlie for the ride, he snapped the reins, sending his horse on a quick trot down the road, dust swirling up in Jemma's face.

She stared after him for a moment, spitting out sand. Picking up her suitcase, she pushed the gate, which opened with a creak. As she drew closer to the house, she noticed details not visible from the road. The white wasn't as pristine as it had appeared from a distance. A light coat of dirt, like settled neglect, tarnished it some, as did the weeds sprouting between porch boards. A large number of tiles on the gabled roof were loosened, their edges not lying flat on their neighbors but curled up like snarling lips. A huge dogwood tree to the left of the lane should have been in bloom in this climate, but pink petals littered the grass below it, leaving most of the branches bare, reaching into the air like crooked and clutching fingers.

Jemma slipped her gloves back on, and at the front door she hesitated before touching the dull knocker in the shape of a grotesque head. She turned to look over her shoulder at the iron gate, still open, as if waiting for her to run back through it.

Instead, she lifted the knocker and banged it against the door.

Fullepub

Fullepub