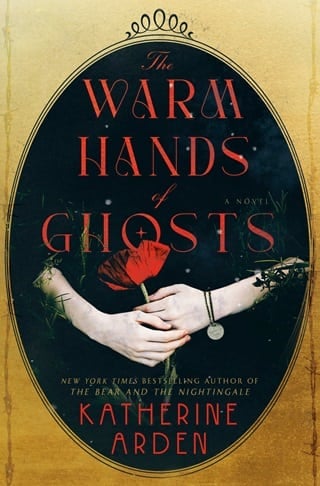

Chapter 34: To Lose Thee Were to Lose Myself

FALAND’S HOTEL, PARTS UNKNOWN, FLANDERS, BELGIUM

Winter–Spring of 1917–1918

Freddie still didn’t tell Faland about the pillbox. Sometimes he thought it was mere pointless defiance, not giving Faland what he wanted. Sometimes he thought he couldn’t bear to forget Winter’s eyes.

He didn’t know. But he wouldn’t talk about the pillbox.

Faland didn’t give him another candle to leaven the darkness, and he didn’t come now when Freddie woke up screaming. Freddie started to wander the empty hotel by day, shuddering at every whisper. Sometimes he glimpsed the dead man waiting around corners.

The wine turned sour on his tongue, like it was corked, and even the mirror, though he stared at it with a madman’s desperation, began to seem insipid. He’d look at Laura’s face and think, She’d never smile at me like that, she’d ask me what the hell I’m doing.

Winter wouldn’t smile either. He’d tell me I have a duty.Real people were difficult and hurt you, and left you, and no mirror could ever…

And still he told Faland stories. Other stories. But they’d all grown so vague. He’d grope for words sometimes, grope for the sequence of events, and shake as he spoke, as though his very soul were a wall beginning to crumble. He almost begged Faland to play the violin, to remind him of his forgotten self. But he was afraid of the person whom Faland might conjure, afraid he wouldn’t recognize him—or perhaps that he would, only too well. So he bit the words back.

Sometimes, as he walked the hotel corridors, Freddie told himself he was trying to find the door that led out, but he wasn’t. He didn’t have enough hope left to really try. All his doors were locked, and the hotel was his entire world.

Finally, every time he slept, he woke screaming.

But he still would not let go.

“Tell me,” Faland said, avarice still lurking in his eyes, his voice gentle enough to make Freddie want to cry. “And be at peace. I’ll make such music of you, Iven.”

He was going to yield eventually. His mind was failing. He knew it, and Faland knew it. Tell him now, he thought. Don’t wait until you’re an empty wreck.

Faland seemed to sense the change in him. His lighter eye glittered.

But then between one terrible hour and the next, some utterly unmarked space of time later, three women walked into the hotel, and one of them was his sister.

She was pallid, filthy, and soaked. She looked the way he imagined she might have, dying wounded in the mud at Brandhoek, her hair plastered to her neck, the scars prominent on her hands. Perhaps she was a ghost, like the drowned man.

And then he thought, with a strange quiver of his heart, would a ghost look so very much as she’d looked in life? Irritable at being wet, her expression skeptical, watching Faland finish playing his violin and ply them all with wine? Would she be so painfully real, so as to reduce the image in the mirror to a vague sketch, sfumato, without life or self?

Would a ghost make all his absent memories hurt so much?

And then Freddie glimpsed Faland’s face, and stood very still. For he could have sworn Faland was angry, even perplexed, even though he’d crossed the room smiling, and then the thought broke through the haze in his mind like a ninth wave: That’s my sister and she’s in the hotel and she’s alive.

He lurched forward. But Faland flickered a glance at him and the thought shattered into shards of Is that really her? It can’t be her. And even if it is her, why would she want me? I’m not Freddie anymore. I’ve forgotten too much, changed too much. I’m no one.

With clenching hands, he saw Faland bring them wine. Saw one of the other women, the beautiful one, go to the mirror. Heard her scream. The mirror made men cry, but scream? Freddie glimpsed a flurry of motion in the woman’s reflection, a red like blood.

His sister was on her feet, her face full of concern. She limped when she crossed the room. Why was she limping? He wasn’t even aware of moving toward her. Blind instinct was deeper even than the apathy Faland had nurtured in him. That was Laura, and she needed him.

Then he saw Laura see him. To his shock and fear, and something too painful to be delight, he realized she was staring into the mirror, staring back at him. She could see him in the glass. He couldn’t look away. Their gazes locked, and he half-saw her turn round, heard her cry, her living voice calling “Freddie!”

I must be the same, because she knows me. Faland doesn’t. He just knows the pieces.He shoved toward her. Then the crowd got between them. He had time to hesitate, to think, Does she?Who are you now, Wilfred Iven? The memory of who he’d been wavered in the half-fallen edifice of his mind. He didn’t even know all that had been lost between them. His limbs were weak; had he drunk so much? He thought he saw Faland standing by his sister, hands clamped on her shoulders. When he tried to cry a warning, no sound came. The crowd was so thick. Where was she? Now he glimpsed Faland standing face-to-face with the beautiful woman. Her golden hair was a few shades darker than his. She was shaking her head.

Faland’s lips moved. He was smiling. “No?” he said.

He couldn’t tell if it was rage or terror on the woman’s face. Unholy delight on Faland’s. Where was Laura? He was trying to call her name.

Then the world dissolved, and he jerked awake, again in his own bed, with a sick headache. He lay there gasping, eyes shut tight, trying frantically, as he had so many times before, to figure out what was real, and what he’d already lost in the wasteland of his mind.

Fullepub

Fullepub