Scene 53 Take 1

I couldn't sleep.

On the fourth day, Seren called in the middle of the night. I was lying in bed, still fully dressed, staring at my ceiling.

I knew, before I answered my phone, why she was calling—what she would say.

I'd known since that first morning. I'd felt it in my soul.

It didn't stop me from clinging to a fraying thread of hope as I answered my phone.

"They found her. She's gone." It's all she said. All I could understand. And then the stoic, ever-poised, ever-proper sister of the woman I loved most in all the world was crying. Sobbing. Wailing on the other end of the line.

I must have said something. I don't think I just hung up. I don't know if I hung up at all.

I got up, walked across my bedroom, and collapsed in the hall.

I lay there on the cool marble tile, with my cheek pressed to the floor. I didn't cry. I didn't move. I didn't breathe. If my heart still beat, I no longer knew it. I simply felt nothing.

And then, as the seconds ticked away, as reality set in—it hit me: a sudden, crushing, turbulent cataclysm of emotion. A violent surge of hysteria ripping through the numbness. It swallowed me whole.

Somewhere, a high, wavering, desperate noise pierced the air, and it took a moment to realize the sound was coming from me. I pummeled the floor—screamed and screamed and screamed. I didn't care who heard me. I didn't care about anything.

My beautiful, extraordinary, perfectly imperfect Dillon Sinclair was gone, lost forever. Three days before her thirty-first birthday.

The truth struck me in searing, agonizing waves of pain—the dawning realization that I'd never see her again. Never kiss her chapped lips, never smell the sea in her hair, or hear the smile in her voice when she called me Kam-Kameryn. I had held her for the last time.

Our final conversation had been curt, my temper short, her voice distant. I hadn't understood. I hadn't begun to imagine…

An entire new cascade of anguish overcame me, a nauseating guilt racking my body.

No! It wasn't possible. I slammed the heels of my hands into the wall. Seren was wrong. Wrong!

It couldn't be Dillon. I needed to call her back. Ask if they were certain.

But I didn't. Because deep down, I knew.

She'd bought a train ticket to Swansea on her credit card that morning, then taken a cab to Mumbles Head. A fisherman had seen a woman climbing the stairs toward the lighthouse shortly after high tide.

They'd searched for her for days and found nothing.

And now they had.

Afraid I was going to vomit, I rolled onto my side and curled into a ball, hugging my knees. As if I could hold myself together. As if I weren't coming unglued at the seams.

Fuck her. Fuck her. FUCK HER! How could she do it? Leave me like this? Like she'd never loved me at all.

At some point, I crawled to the balcony. The sun had risen. A sun that had no right to rise. I lay there, half-in, half-out of the open glass doors, listening to the sounds of the city waking beneath me. How could the world keep on turning when my life was falling apart?

I couldn't bring myself to get up. On hand and knee, I pleaded with a God I no longer believed in to let me sleep, to wake, to find it was all just a dream—the continuation of a neverending nightmare. That I would open my eyes and find it was four days earlier. That I would have a text from Dillon, saying she'd won Leeds. Saying she was on her way home.

But each time I dozed off, exhausted from insurmountable heartache, I'd wake once more, only to relive the stabbing, undeniable actuality that this was real—and lose her over and over again.

And so the cycle went—for hours. Days. Weeks.

My mom came and stayed with me. She brewed tea that grew cold on my end table, held my hand when I would let her, called my agent and manager. She made meals I never touched, and comforted me as I wailed with grief in the middle of the night, or broke down in sobs at my breakfast counter.

My manager rescheduled my studio pick-ups, citing ‘a death in the family.' I wanted to come clean, to explain Dillon, but she convinced me to keep it vague.

It wasn't the time. I wasn't in the right frame of mind. Later, maybe .

I was in no condition to fight her. And she wasn't wrong. I couldn't function. I could hardly brush my hair—dress myself.

On more than one occasion, I stood leaning over my balcony railing, staring at the courtyard thirteen stories below. I thought about jumping. I mean, I thought about it in the way any disconsolate, bereft, heartbroken lover might think about it: not with any real intent (I didn't have the nerve for that), but with the wish that I could. Anything to relieve all the hurt, all the pain I was suffering.

I'd sit and watch our piling beneath the pier for hours, desperate to remember every detail of that night: our first "real" kiss, the water lapping at our feet, the way she'd lit my world on fire. I could feel the warmth of her fingers pressed against the small of my back, taste the mint tea on her tongue. I fantasized details I couldn't remember, preventing myself from turning to hysterics when I couldn't recall things that didn't matter—the color of her shoes, the way I'd worn my hair, the location of the North Star.

I'd play little head games with myself, making negotiations with the universe: if I could count fifteen hundred waves break on the shore without blinking, if I could hold my breath for one hundred revolutions of the Ferris Wheel, if I could trace the path of a falling star all the way to the horizon—a portal would appear on my balcony, something I could step through, allowing me access to join her—wherever that might be. They were always unachievable tasks, impossible victories—games that I could never win.

I knew it was all bogus. I wasn't actually crazy. And when I grew tired of torturing myself, I'd slip to my knees, press my forehead against the glass railing, and cry.

Countless days I spent trying to figure out what I could have done better for Dillon—and even longer nights dwelling on the ever-pressing, impossible question: why ?

Why had she done it?

She never left a note, never explained herself. The text I received that morning was the last thing she ever sent—my response permanently unread.

Her bike sat in the corner of my living room; I couldn't bear to move it. Some days, I'd pour whiskey over a glass of ice, and by the time I shifted to drinking straight from the bottle, I'd talk to the bike as if it were a conduit allowing conversation between the living and the dead. I'm sorry , I'd tell it, over and over—for failing her, for not doing enough to make her feel like life was worth sticking around. And then again, as the contents of the bottle emptied, my focus would inevitably shift to seeking resolution it would never find.

Why, why, why?

I wanted to imagine she was drunk when she jumped. That an outside influence forced her to believe having no life was better than the life she left behind. But her toxicology report had been clean, without a single drop of substance in her body. She'd stood on that ledge, clear-headed and sober, and made her last decision with a sound mind.

Had she planned it on the seven-hour train ride to Wales? Had she climbed the steps to the lighthouse knowing she'd never walk down? Or had it been a rash decision, a shortcut to a palliative end?

Alone, just her bike and me, I'd tip back the bottle, drowning in my sorrow, and wonder if she tried to swim… if she regretted jumping in? If she'd ever given a single thought to the hurt I would feel, the loneliness I'd face being the one left behind?

They were answers that died with her in the wild seas of the Gower.

When I finally returned to the studio to finish pick-ups for Sand Seekers , everyone gave me a wide berth. I looked like hell; my skin was ashen, I'd chopped my hair above my shoulders with a pair of kitchen scissors, and all my costumes were too big. Hair and makeup had their work cut out for them, but I didn't care.

No one mentioned Dillon. The rumors circulated—I wasn't unaware—but the subject remained taboo. I wanted desperately to publicly grieve my loss, but under the advice of my PR team, and gentle, yet insistent persuasion from Elliott, I remained slammed in a closet I had never wanted to be in. It was for the best , everyone kept telling me. For who , they never said.

Somehow, by the grace of the Gods of Entertainment—along with a healthy dose of get-your-shit-together from L.R. and MacArthur—I got through the final photography and completed the film.

It should have felt monumental—the closure of an era in my life I would never experience again. The trilogy was finished; my journey as Addison Riley complete. Tears should have flowed freely at the wrap party, with hugs and toasts for the cast and crew who I'd learned to love like family.

Instead, I spent the night nodding through an unconvincing smile beside one of the soaring atrium windows of the Ritz-Carlton, silently contemplating how long it would take to get home through traffic on the Santa Monica Freeway.

I ended up leaving in the middle of a blooper reel documenting hilarious moments of the three-year odyssey. I couldn't stand the footage of me laughing, reminders of how happy I'd once been. On the way home, I got a phone call from Dani. I canceled it to voicemail. We hadn't spoken since my party. But as the car turned onto PCH, I was overtaken by an abrupt explosion of fury. I asked my driver to stop, and stepped into a sea of taillights, crossing the highway to the beach. And there, amongst the littered wash of Venice sand, I hit redial, and proceeded to tell my once-best friend exactly how I felt about her. When I hung up, I knew we'd never speak again. It was cathartic, I guess, cutting out a cancer in my life. But as I cried myself to sleep that night, it still didn't return Dillon to my side.

Later in the summer, when the Olympics came to town, I tried desperately to hide in a fog of oblivion. But all the whiskey in the world, the shuttered blinds, the hum of self-guided meditation, the glow of Netflix, and the mind-numbing sting of scorching showers failed to permit me to escape the sight of those five interlocking rings. The city pulsed in blue, black, red, yellow, and green.

Seren called the Thursday before the start of the equestrian competition. We'd spoken little since Dillon's passing, neither of us having much to say. We were both wading through our own personal hells—ironically less than a hundred miles apart. I knew she and épée had arrived in Los Angeles. I'd seen a headline: Seren Sinclair elects to remain on Team GB after the death of famed Olympic sister .

She asked if I would come to watch her. If I would sit with her mam.

I don't know why it felt so important. Dillon wasn't there. And I wasn't a Sinclair.

I wanted to say no. If I'm honest, after attending Dillon's private funeral, I wasn't sure I wanted to see Seren or Jacqueline again. A shamefaced, self-condemning side of me worried they might blame me for the loss of Dillon. I was the one, after all, who had found Dr. Monaghan. The one who had supported her in her quest to qualify, and encouraged her to compete again. I was the last person she texted. The one who hadn't read the signs. If I hadn't been so blind, perhaps Dillon would be alive.

But neither woman had ever given any indication that was true. It was just my guilty conscience talking, playing tricks on my mind.

So I told her yes.

I had no excuse to say no. I wasn't working. I'd had to buy my way out of my contract for Anna Karenina . The Tolstoy film felt too dark, too painful in my present emotional deterioration. I wouldn't begin filming the Mia Hamm project until winter. Until then, outside my obligation for the press tour for Sand Seekers , I was taking time off, trying to pull myself together. Trying to find a way to feel whole—no, not whole. I didn't imagine whole was in my future. That would be like trying to put Humpty Dumpty back together again. Operational, maybe. Functional, at best.

But I owed it to Dillon to be there for her sister. Despite my professional stance that she and I had never engaged in a romantic relationship, I'd never denied we were friends. Going in support of the Sinclair family felt like a satisfying fuck you to my publicist, my agent, my manager. Every person who continued to pressure me to live in hiding.

So I went to the competition.

I was glad to be a hundred miles away from LA at the equestrian grounds when Elyna Laurent won the women's triathlon. The bike leg of the race had taken a course down PCH, traveling through Santa Monica. It would have dismantled me to stand on my balcony watching the triathletes cycle past without Dillon.

Still, sitting in the crowded stands awaiting Seren's dressage test, I'd been unable to scroll past Elyna's photo on the podium. I stared at her stiff smile, Dillon's gold medal around her neck, Henrik's ever-present shadow blurred in the background.

I wanted to excuse myself, to go puke in the VIP bathrooms.

Instead, I forced my thumb to click unfollow on World Triathlon and turned my focus back to Seren.

Baby steps . I could practically hear my therapist applauding.

My mom flew down to stay for the weekend, joining me to sit with Jacqueline. While the two of them made polite small talk, I daydreamed of an alternate reality, and stared at the leaderboard.

Sinclair: #1

On the third day, going into stadium jumping, Seren was sitting in a position to win the individual gold.

But it was the wrong Sinclair. Another should have been there in her stead.

Seren must have felt the same. Because when she did win—when the President of the FEI placed the medal around her neck—she sank to her knees and covered her face with her white-gloved hands. Cameras panned-in, international footage rolling as an instrumental of God Save the King played in the background, Seren Sinclair sat on the podium and sobbed.

I had to leave. I didn't wait for my mom, or say goodbye to Jacqueline, or alert the team of security surrounding me. I simply got up, shoved my way to the aisle, and ran down the stairs. I didn't care if the press caught my hasty exit—if they photographed the mascara running down my cheeks. I only wanted to escape. Back to the prison of my apartment. Back to the comfort of Dillon's bike and analgesic influence of the whiskey. Back to the seclusion of my misery.

A few weeks later, Sam called. We'd kept up a tentative friendship, the two of us needing one another, both hurting in equal, horrible, dissimilar ways. She told me she'd talked to Seren. After the Olympics, Seren had gone home and left the medal on Dillon's grave.

Sam said the next day when Seren went to the cemetery, the medal was gone. She hadn't cared. She said it never belonged to her in the first place.

The gold medal ambitions had always been her sister's. And now they were all lost—Dillon, the medal, the dream.

It took me a long time to understand I didn't kill Dillon Sinclair.

Years, if I'm honest. A journey through unconquerable heartache. Hours upon hours of endless therapy. Midnight calls to my parents. Unannounced drop-ins on my friends. It was a one-step-forward, two-steps-back, nonlinear kind of healing.

It was only when I finally came to terms with the acceptance that I could not have saved Dillon without her willingness to save herself, that I was able to let go of some of my guilt. There would always be things I could have done better—but the blame wasn't solely on me.

My therapist allowed me to explore my what-ifs —what if I had done this, what if I had done that—and then bade me put them to rest. I had done the best I could with the information Dillon made privy. Some things were out of my control, and always would be.

With the lessening of my guilt, a more uncomfortable emotion came to pass: anger. I didn't know how to forgive her. Forgive her for the hurt she put me through. Forgive her for the future she stole from us, without ever giving me a choice in the matter.

I grew obsessed trying to understand suicide, trying to understand the darkest places depression lured a person. Trying to understand how someone could see no other way out, no other relief from a pain so visceral, they felt there was no alternative. See the person, not the act , my therapist drummed into me. She reminded me I needed to remember Dillon for who she was, not for the decision she made during a time of intense emotional suffering.

Compassion was imperative—both for her and for me.

But even still, even as I grew to accept it—even if I knew I would never fully understand—the truth remained: I lost someone I wasn't prepared to live without, and the despair of that will never go away.

It's been two years now, and I still cry. Probably more often than I should. Certainly more often than I'd admit to anyone. But not as often as I used to. It's when the sun hits just right —when a breath of chlorine and sunscreen touch the air—I can feel her, somewhere near me. Never close enough. Forever out of reach. And when that happens, wherever I'm at, I have to sit down—to try to catch my breath. To try to keep myself from crumbling.

I fail, frequently. All the king's horses and all the king's men… But I've learned to continue. To get up, dust myself off, and try again.

I still wear the necklace she gave me. Aside from filming, I've yet to take it off. Dillon was right; I haven't been invited to the Met Gala—but I did get nominated for an Oscar for my portrayal of Mia Hamm. And win or lose, I'll be wearing my Welsh lovespoon in front of the Academy.

Elliott keeps telling me it will get better. Maybe he's right. He says one day I'll find someone—that I'll look up, when I least expect it, and catch a smile that makes my head spin and my heart feel things that currently no longer seem possible.

I like to think that's true.

But it probably won't be on a Hawaiian island. I probably— hopefully —won't run them over with a rented Jeep. Our first kiss is unlikely to taste of pineapple.

I just know, whoever it is, they won't be Dillon Sinclair. And I'll never be their Kam-Kameryn.

Because the truth is, life isn't fair. Not every love story has a Hollywood ending.

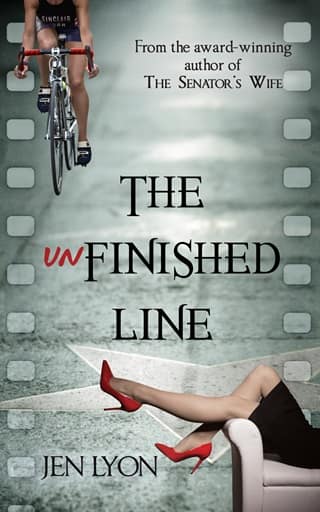

But here's the thing: that hasn't stopped me from feeling like our story was an unfinished line—like someone hit pause before the credits were rolling.

And it makes me wonder: what might have happened if a different choice had been made? If life were more like a movie, where a director could call ‘cut' when a shot wasn't working? Where the actors could go back to firsts, the crew could reset, and we could rewrite the scene. How different would our future be if we could film the take again?

Quiet on set!

Take two.

Roll sound!

Roll camera!

Action!

Fullepub

Fullepub