Chapter 66 Annie

CHAPTER 66 ANNIE

April 2013

Bolton Landing

The highway was a blur of pavement out my window, and something about being on the Northway again had my brain picturing Sidney, that covert trip to my hometown that ended with her sitting in my car, telling me Amanda was dead. I let that scene run again and again, searched for the lie that I now know I should have spotted. Was it in her eyes? No, couldn’t find it there. In her words? Not there either.

Fucking Sidney—she was good. I ran my left hand through my hair. I’d underestimated her. I’d known she was needy, of course I’d known that, but I’d thought it was garden-variety need. Like, blocked-number after breakup, worst case. What a profound miscalculation. Sabotaging my relationship with Ryan felt quaint compared to this new revelation. I tightened my hands on the wheel. But my anger at Sidney was quickly morphing into something much more potent: regret. I could feel it roping around my heart.

I had never loved Sidney. I had never even liked Sidney! So then why was she there in the first place, inside my car, and why had I let her kiss me, and why had I kissed her back, and why had I done any of it when every moment with Sidney made me sad, my whole self wishing she was Amanda.

I rolled down the windows and let the air mess my hair. Then I put my hand, balled into a fist, outside and let the wind slowly pry my fingers apart.

As I drove the last stretch into Bolton Landing, I felt—well, fuck, there’s no single English word for it. Amanda used to love learning words from other languages that captured meanings ours never could. It started with schadenfreude , which Mr. Riley said at some point, talking about what it’s like to be an understudy, and all of us gave him some side-eye, so he slowed down and explained the definition.

“But, like, ‘malicious joy’ or ‘gloat’ doesn’t even begin to capture that meaning,” Amanda was saying, absolutely amped about this word and the thing it named. “It’s like knowing the word unlocked the feeling. It’s crazy.”

“It’s cool,” I said, and in response she shoved me playfully.

“Um, it’s more than cool.”

After this, whenever she heard a word that did this for her, she’d bring it to me and explain. Always the same energy, too: hands moving, talking a mile a minute. One time she brought up the Japanese word boketto . A clumsy translation might be zoning out, but that’s not quite right; it’s more like non-doing or cultivating stillness by staring into the vastness.

I was staring into the vastness now. Both hands on the wheel, straight ahead, boketto . Landmarks passed outside the window, and deep in my mind they sparked memories but they turned to dust as soon as they formed.

My old building was on my left, those same green plastic Adirondack chairs. My eyes were not on the road, but past it and through it, boketto . The library, the coffee shop, the high school. Then I turned left. I parked outside Amanda’s old house. I cut the engine, and when I did, I cut off whatever invisible thread was tethering me to the alternate universe, and that was fine with me. It was this universe I wanted to be in, anyway, because now I knew this was the one with Amanda still in it.

After knocking a few times and waiting long enough to be certain, I walked down the street to the diner that looked exactly as it did when I left. I wondered if they’d think the same of me. It was lunchtime, and the place was empty except for two construction workers sitting at the counter halfway through their burgers and fries.

A middle-aged woman carrying a plastic menu came to seat me, gesturing for me to follow. I reached for her, gently touching her arm, and said, “Do you know Amanda Kent?” She turned and the way she looked at me reminded me of the feeling I would have, all those years ago, about outsiders who came in expecting things. My car keys were in my hand, and I glanced down and wondered if I was holding them like they were a sexy prop, wondered if to this woman I seemed like city money and carelessness. “I used to live here,” I said, surprising myself with how much pride I felt in that fact.

Her shoulders softened. “Well, hon, best I can say is that Amanda would be over at the school. Now, can I get ya anything?”

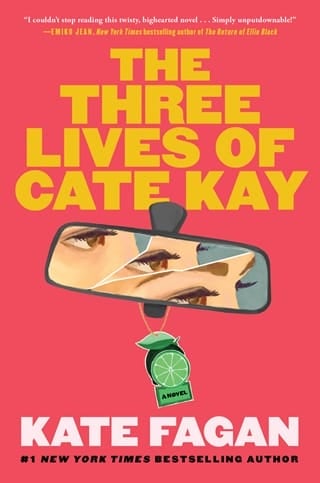

“No, thank y—” I began, but then a flash of memory. “Actually, yes—a slice of key lime to go, please.”

Auditorium doors are oddly noisy. Amanda and I used to wonder why. Each time they opened, especially when you needed silence, they sounded possessed, like the entire energy of the room went rushing toward them along with the audience’s attention. Bad engineering, maybe. Keeping this in mind, it took me many seconds to turn the brass handle of the heavy door—I did it slowly as if sneaking out for a party. Finally, I turned sideways and slipped inside, and nobody on the faraway stage was the wiser.

I suddenly realized that all I’d ever really wanted was the universe’s permission to come home. And maybe I wrote The Very Last as a way of asking for it. I think. I don’t know. Maybe that’s all bullshit.

Then I saw Amanda onstage, her movements still so generous and assured, just as they had always been. I could have spotted Amanda from any distance. Right then, she was showing a student the precise spot at which she needed him to stop, and she rolled herself there in one quick motion then spun herself out toward the imaginary audience with a dramatic flourish.

And it was then that she saw me. Maybe she also knew my body’s movements from any distance, had looked out at the woman leaning against the back wall holding a slice of key lime pie, one knee bent, foot propped against the wall. Maybe to Amanda that silhouette screamed Annie. How sublime the feeling, to be known again.

She stopped midsentence and stared at me, and it was like her vision created an energy. I felt it on my arms first, the hairs standing on end, tingling. The feeling was pleasantly terrifying, as if my soul was warming itself by a wildfire.

Then she turned her head slightly toward the students waiting patiently behind her and said, “Start again at the top of the scene.” That sent the kids into a flurry of movement, and they were the backdrop as I watched Amanda wheel herself off the stage to the front row so she could assess them as an audience member might. Mr. Riley used to do the same thing.

For a moment, I wondered if maybe she hadn’t seen me, maybe I’d misread the moment, but then I closed my eyes and I swear the energy had an actual heartbeat, it could make flowers bloom, light bulbs pop. Amanda had seen me, was waiting for me, and I shouldn’t keep her a moment longer.

I pressed myself off the back wall, carefully walking down the aisle as if I’d arrived late for opening night. When I reached the front row, I made myself small and shifted across the many seats so as not to block the view of the make-believe audience behind. Amanda kept her eyes fixed on the stage the whole time, even as my left hand silently pressed down the seat next to her, even as I eased into it, settling, the little box of key lime pie on my lap. We were now inches apart. She was staring at the students, who looked prepared to restart the scene.

“Ready when you are,” she called to them, and I seized the moment for myself, turned to her and opened my mouth to say her name. But as I did, she lifted her right hand and silenced me. The glow of the stage lighting was glancing delicately off her lovely features, and at least this soothed me. No matter what else had changed, no matter how brutal whatever had been, and whatever was about to come next, this remained: Amanda, beautiful in every setting, at every stage.

The students began the scene, and my mind started running through what to say when they were done. I took one long, deep breath and tried to tune in to what was happening onstage. Perhaps I could figure out what play they were doing. But my mind was too crowded with thoughts— had I read this all wrong? did Amanda actually hate me? and what will I do if she does?

We sat like this for minute after minute, Amanda’s attention laser-focused on the stage. Finally, she leaned slightly into me, her eyes still on her students, and instinctively my body responded, leaning into hers. She tilted her head toward me a few degrees, now closer to my ear, and the moment was like a thousand others we’d had growing up—whispering so only the other could hear.

She paused and held us like this, still watching the stage. Then I spotted it. And I watched as the young man strode confidently, hit his mark, and spun to face out, his eyes gleaming. Beside me, I heard Amanda’s satisfied exhale as the boy’s classmates hooted and hollered, the imaginary curtain dropping on Act I.

“So,” Amanda said, turning to me and nodding at my lap. “We gonna eat that or what?”

Fullepub

Fullepub