Chapter 50 Amanda

CHAPTER 50 AMANDA

October 2007

Bolton Landing

True to my word, I didn’t go back to AA the next night. Or the night after. But one Friday eight months later, about the time I thought Kerri would be coming home for the weekend, I heard a rap at our door then the creak of it opening. I was in the den watching the afternoon talk shows, and I called out, “Hello?” A second later, Patricia Callahan appeared, and she said, “We missed you, so I thought I’d come check on you,” and I could hear in her voice that she understood the risk she was taking coming to see me, that I might demand she get out of my house. It was this small quiver of doubt—along with my secret weapon: the truth about The Very Last —that kept me from yelling at her to get the fuck out and never come back. Instead, I said nothing, which was the best I could do.

“I rented a van—would you like to go for a drive with me?”

Before I could say anything, she shook her head and said, “Let me rephrase that: even if you don’t want to, would you consider going for a drive with me?”

This version of Patricia Callahan was disarming. She was clear-eyed and warm, and as had been happening more lately, my heart hurt for Annie. Standing before me was the mom she had longed for, but who she wasn’t here to experience—it made me sad. But still, I reminded myself, that was her own damn fault.

“I would just love to spend some time with you,” Patricia was saying, readjusting the strap of her purse on her shoulder. Right then Kerri came home, flying through the front door, calling out “Amanda!” as if she was worried. She stopped abruptly when she saw Patricia, though I wasn’t sure if they’d ever met before. Kerri ignored her, turned her attention to me, “Whose van is in the driveway?” Patricia lifted her hand and said, “That would be mine” and after years of feeling isolated, visits from friends petering out quickly, I felt a surge of adrenaline at having two people vying for my attention. My blood started rushing like I was in a performance again.

“What’s going on here?” Kerri asked me.

“Patricia, this is my younger sister, Kerri,” I said, and I noticed how good it felt to act like a normal person, the kind who remembers to introduce two people who haven’t met before. Civilized and mature is how it made me feel. Then I added, “She’s taken care of me,” so that Patricia would remember who hadn’t taken care of me and whose karmic scale was imbalanced.

She extended her hand. “Kerri, it’s so wonderful to meet you, although I do believe we’ve met once, when you were much smaller, at one of Amanda and Anne Marie’s plays.”

Kerri’s eyes flew to mine, and she seemed to be searching for confirmation, which came a few seconds later when Patricia said, “I’m Anne Marie’s mom.”

Brave of her, I thought. Walking into our house, right into the belly of the beast, and claiming ownership over Annie in a way she had never done when Annie was here and worth claiming ownership of. Sometimes Annie had even wondered aloud if her mom, when out at the bar or with a new guy, pretended she was childless.

Kerri was the nicest girl in the world, so she turned to me and said, “Are you okay?” and I told her that I was. What I was feeling, for the first time in a long time, was curiosity—as to what Patricia had to say, as to what had changed. And before I could filter it out, another thought: I needed to do some reconnaissance work on Annie’s behalf.

“We’re going to take a ride,” I said.

Patricia drove us around the lake. What I’d allowed myself to hope for was that she’d heard directly from Annie. But she told me right away that she hadn’t. My disappointment surprised me. Tears, actually. And I prayed that Patricia wouldn’t notice, kept my head turned toward the window, but she reached over and covered my hand with hers, squeezed once. I wondered if she blamed herself for Annie, but I couldn’t bring myself to ask. A question I’d asked myself a thousand times: What exactly did Annie owe me? Because we were best friends, because we had plans together, because she was there when I fell, did all of that mean that her life was forever tethered to mine? When my life suddenly became profoundly stationary, did she have to clip her own wings in solidarity? No, of course not. But also yes, a little bit. Why was I mad at Annie when what she did—leave—was what I would have asked her to do? No matter if she’d stayed and left later, or left when she did, my life right now would be exactly as it was. And yet.

“Are you mad at Annie?” I eventually asked. Patricia had already told me her story, how she didn’t realize Annie was missing for two full weeks. She had known nothing about my accident, was shacked up at a cabin a few towns over, until a police officer stopped by the Chateau during one of her shifts. That night, she went home and started digging through Annie’s things and came across this old T-shirt with Tom and Jerry on it that apparently Annie wore nonstop when she was a kid. She laid the shirt on Annie’s bed and stared at it, remembering how angry it had made her but not remembering why. She said that at first that shirt was her kryptonite, but eventually became her talisman.

She was gripping the wheel with her right hand, then brought her left to her chest and fiddled with a necklace. She tried to show it to me, but it wasn’t long enough to see, so she explained that it was a present Annie had given her for Mother’s Day long ago—fifth grade, maybe? A chintzy little thing with enamel renderings of the cartoon characters from that favorite shirt. Patricia had never worn it, but now refused to take it off.

“No, I’m not mad at Anne Marie,” she said.

I had intended to hurt Patricia with The Very Last . Another item on the list of things she didn’t know about her daughter. Really dig the knife in and twist. But I realized on that car ride that Patricia Callahan wasn’t a monster; she was just a broken woman piecing herself back together.

She parked in front of my house and cut the engine. She dropped her hands from the wheel and looked at me. “This has been so nice, Amanda,” she said, raising her hands to her heart as if it had been soothed. As cheesy as Annie would have thought the gesture, and it was a little cheesy, it made me feel good. Then she reached over and put her warm open palm on my cheek, looked me right in the eyes, smiled. The intimacy comforted me. I wish it hadn’t. It felt traitorous, but it seemed that I also craved Patty Callahan’s love.

“I wasn’t sure I was going to say this, but…” I paused.

I suddenly had the desire to set aside my weapon, my trump card: knowing about The Very Last . My intimacy with the book and how it captured our memories still made me feel close to Annie, and in this moment, I wanted to give a piece of that to her mother, too.

I turned my head toward the window, looked at the chaos of our side yard, where my dad tinkered with old engines and car parts, and asked, “Did you ever read The Very Last ?”

“ The Very Last ?”

“The book,” I said. “It’s going to be a trilogy, the’ve already announced the second book. I think there’s a film coming for Christmas, too.” I looked down. Her hand was covering the gear shift, and I admired its delicateness, its loveliness.

“No, I haven’t,” she said.

“Well, maybe go get a copy,” I said. “Go get it—please.”

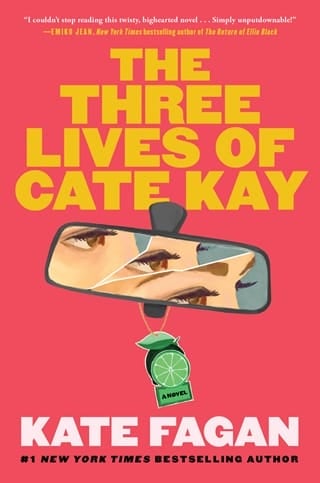

That night, I stared at The Very Last on my bedside table. Without my consent, the book began morphing. Becoming less the embodiment of my anger, more a lifeline to my best friend, and I couldn’t stop myself, I cracked it open again. This second read was an entirely different experience.

Cate Kay.

Cate with a Kay.

Cate with a K.

Cate with a motherfucking K.

Fullepub

Fullepub