Carly

Fell, New York

February 2018

Three Months Later

CARLY

It got cold that winter. The snow started early in December and didn’t let up. The winds were icy, the roads hard. I barely made it home to Illinois for Christmas.

I stayed with my brother, Graham, and his fiancée for three days. Then I got back in my car and drove back to Fell.

Graham and Hailey didn’t understand it. Why I wanted to be in Fell, of all places. Why I didn’t want to leave. Why Fell, the place where our aunt had committed murder and pretended to vanish, was home. But it was.

I stayed with Heather for another month, and then I moved into Viv’s apartment on the other side of town. Most people would think it strange that I would take over my aunt’s place after she was indicted for murder—specifically, voluntary manslaughter—but Heather didn’t. “Why not?” she said when I suggested it. “It fits in with the rest of this weird story.”

So I moved in. I quit college—another pissed-off lecture from Graham—and researched what I really wanted to do. For the first months of winter, I lived a quiet life. I read books. I walked. I hung out with Heather. And I spent dozens of hours, days, in the Fell Central Library, reading and researching. Thinking.

Callum’s autopsy showed that he had died of a brain aneurysm that night at the Sun Down. A quick and painless death, apparently. I was glad he hadn’t suffered. There was a funeral, but it was small and private. I wasn’t invited, and I didn’t attend.

The body of Callum’s grandfather, Simon Hess, was officially identified by police in early December. The cause of death was two stab wounds, one to the chest and one to the neck. The neck wound, said the coroner, had likely been the one to kill Hess, though if left untended the chest wound would have done it in time. The murder weapon was not found on the body, though it was determined to be a hunting knife, very sharp, the blade four to six inches in length.

Vivian Delaney’s defense claimed she had killed Hess in self-defense when Hess admitted to her that he was a serial killer. It made state and national headlines when Hess’s DNA was matched to the DNA found on Betty Graham, Cathy Caldwell, and Tracy Waters. There was no DNA found on Victoria Lee, since she was killed in haste and not raped.

Betty’s, Cathy’s, and Tracy’s families found closure. Victoria’s did not.

I didn’t go back to work at the Sun Down after that night, and neither did anyone else. The building was damaged from the roof to the foundation. Chris, the owner, tried to keep it open, but there were no customers and a county health inspector informed him that he had to close it down. The mold and the damp were a health hazard, the plaster ceilings and walls were starting to crumble to inhalable dust, and the heat didn’t work in the cold. The water pipes froze and the electricity went out, the sign going dark for good.

So Chris did what any sensible man, saddled with an unwanted and unviable business, would do: He got an insurance payout, put the land up for sale for next to nothing, and had the building condemned.

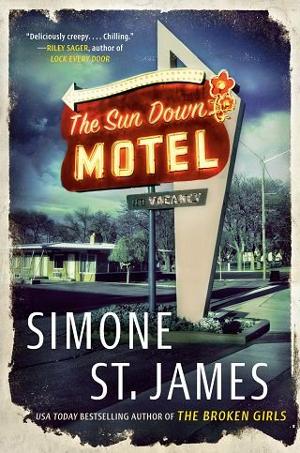

In late December, just after Christmas, a quick chain-link fence went up around the Sun Down, laced with signs that said PRIVATE PROPERTY. The motel sign came down and was carted away in a specialized truck. And in February, when the sky was muddy gray and the ground was churned with dirty snow and slush, the bulldozers and other vehicles moved in.

I watched it. I parked my car on the side of Number Six Road and walked to the chain-link fence, my gloved hands in my pockets and a hat pulled over my ears, the wind freezing my nose and my cheeks, chapping my lips. It wasn’t dramatic or even very interesting; there was no one else there to watch as the machines rumbled around the demolition site, pulling down walls and drilling into the concrete of the parking lot. There was no swelling music, no choir or curtain to fall. Just the streaked, darkening sky and the snow starting to fall as the crew worked day in and day out.

Betty Graham wasn’t there. Neither was Simon Hess, or the little boy, or Henry the smoking man. They were all dead and gone.

My phone rang in my pocket as I stood by the fence, and I pulled it out and yanked off my mitten to answer it. “Hello?”

“Victoria’s case is being reinvestigated,” said the voice on the other end. “They’ve pulled all the evidence and are going over it again. Including reexamining her clothes for traces of the killer’s DNA.”

I turned and started walking back to my car. “Don’t tell me how you know that,” I said to Alma Trent.

“Don’t worry, I won’t,” Alma said. “I managed to make a few friends on the force over the course of thirty years, despite my personality. That’s all I’ll say.”

“If they can pull scheduling records, it will help. Viv’s notebook says that Hess was scheduled on Victoria’s street the month she died.”

“I know. I’ve read the notebook.”

“Not recently,” I said. The notebook was mine now; I’d kept it. By now I’d read it a hundred times. “Have you called Marnie and told her?”

“I have no idea who you’re talking about.”

“Of course you did,” I said as if she hadn’t answered. “You called her first, before me.”

“The name sounds familiar, but I can’t say I place it. You’re thinking of someone else.”

“Tell her I said hello.”

“I would if I knew who you mean.”

I sighed. “You know, one of these days you’re going to have to trust me.”

“This is as trusting as I get,” Alma said. “I’m just a retired cop who takes an interest in the Vivian Delaney case. Call it a hobby, or maybe nostalgia for the early eighties. Where are you? I can hear wind.”

“On Number Six Road, watching the Sun Down get bulldozed into oblivion.”

“Is that so,” Alma said in her no-nonsense tone. “Do you feel good about that or bad?”

“Neither,” I replied. “Both. Can I ask you something?”

“You can always ask, Carly.” Which meant that she wouldn’t always answer.

“Victoria’s boyfriend was originally convicted of her murder. But his case was reopened and overturned. I looked it up, and it turns out that it all started when the boyfriend got a new lawyer in 1987. Do you know anything about that? I mean, something must have changed. There must have been some kind of tip that encouraged him to seek a new trial.”

“I don’t know any lawyers,” Alma said.

Right. Of course. Except she knew for certain that the wrong man had been convicted, and that the right man was dead in the trunk of a car. “Here’s the other interesting thing,” I said. “Right after Tracy’s murder, a homeless man was arrested because he tried to turn in her backpack. Everyone assumed he must be her killer. But the case was thrown out because it was circumstantial. And the reason he went free was because he had a good lawyer.”

“Is that so?”

“Yes. That’s kind of strange, isn’t it? A homeless drifter who has a really good lawyer? It sounds like something someone would help out with if they knew for sure that the man was innocent.”

“I wouldn’t know. Like I say, lawyers aren’t my thing.”

I sighed. I liked Alma, but it was impossible to be friends with her. Heather was more my style. “I took pictures of the Sun Down being demolished on my phone. I think Viv would like to see them the next time I visit her.”

“I hear they’re giving her medical treatment in prison while she awaits trial,” Alma said.

My heart squeezed. Despite everything, Viv was my aunt. “They’re giving her chemo, but they don’t know if it will work.”

Viv had cancer again. She was going to either die of it or spend the rest of her life in prison. Maybe both.

Maybe neither.

Either way, there was nothing more I could do.

Did I feel good about that, or bad? It depended on the day, on my mood, on whether I felt anger at what Viv had put my mother through or the ache of missing family or admiration at some of the things she’d done. There were times I felt all three at once. This was going to take time—time that Viv, maybe, didn’t have.

“She beat it once,” Alma said. “She can beat it again. She can beat anything.”

“Jeez,” I said. “It almost sounds like you know her.”

“I don’t, of course, but she sounds like an interesting lady. Tell her I’d like to meet her someday.”

I rolled my eyes. “Whatever.”

“It’s cold out on Number Six Road. Do you want to come by for a coffee? I don’t care what time it is. I’m a night owl.”

“Me, too,” I said, “but I’m not coming today. I have plans.”

“Is that so,” Alma said again. “It’s about time.”

“What does that mean?”

“It means have fun,” she said, and hung up.

• • •Nick was wearing jeans and a black sweater. He had shaved and he smelled soapy. He had long ago moved into an apartment in a third-floor walkup, a small place that was sparse and masculine and somehow homey. He had started a partnership with an old high school friend in a renovation company, and he ran two renovation crews in town. Maybe some of the business came because he was notorious, but not all of it did. When Nick put his mind to something, he could do anything he wanted.

“I want to study criminology,” I said to him as we ate a late-night dinner at a Thai place downtown. “I can start in the spring, get credits over the summer before I enroll for the fall.”

He lowered his chopsticks. The restaurant lighting was dim, making his dark hair and his shadowed cheekbones almost stupidly gorgeous. I couldn’t decide if I liked him better with his insomnia stubble or without.

“Are you sure about that?” he asked me.

“Yes.” I poked at my pad thai noodles. “I think I’d be good at it. Do you?”

He looked at me for a long moment. “I think you’d be brilliant at it,” he said, his voice dead serious. “I think the world of criminology isn’t ready for you. Not even a little.”

I felt my cheeks heat as I dropped my gaze to my plate. “You just earned yourself another date, mister.”

“I have to earn them? This is like our tenth.”

“No, it’s our ninth. The time we ran into each other by mistake at CVS doesn’t count.”

“I’m counting it.”

“I was in sweats,” I protested. “I had a cold. Not a date.”

“I sent you home, and then I bought all of the cold meds you needed and brought them to you. Along with food and tea,” he countered. “It was a date.”

I most definitely still had a crush on the former occupant of room 210 of the Sun Down Motel.

“Well, tonight is going to be better,” I told him.

It was. We finished our dinner, then went to the revue cinema for a midnight showing of Carrie. There were exactly fourteen people there. I held his hand through the whole thing. When it was over and we went outside, it was snowing. We barely noticed on the drive back to his apartment. We were too preoccupied.

Like my aunt Viv said, a girl has to lose her virginity somewhere, right?

Hours later, when I lay warm in bed with Nick’s arm over me, I turned toward the window in the darkness. I watched the snow fall for a long time before I finally fell asleep.

Fullepub

Fullepub