Carly

Fell, New York

November 2017

CARLY

Tracy Waters was murdered on November 27, 1982,” Heather said. “She was last seen leaving a friend’s house in Plainsview, heading home. She was riding a bicycle. She was eighteen, and even though she had her driver’s license, her parents only rarely lent her their car and she didn’t have her own.”

I sipped my Diet Coke. “I know that feeling,” I said. “I didn’t have a car until I was eighteen, when my mother sold me her old one. She charged me five hundred dollars for it, too.”

“I’m a terrible driver,” Heather said. “I could probably get a car, but it’s best for everyone if I don’t.”

We were sitting in a twenty-four-hour diner on the North Edge Road. It was called Watson’s, but the sign outside looked new while the building was old, which meant it had probably been called something else a few months ago. It was five o’clock in the morning, and Watson’s was the only place we could find that was open. We were both starving.

“So,” Heather said, taking a bite of her BLT. She was wearing a thick sweater of dark green that she was swimming in. She had pulled the top layer of her hair back into a small ponytail at the back of her head. She flipped through some of the articles she’d printed out. “Tracy was a senior in high school, a good student. She didn’t have a boyfriend. She only had a few girls she called friends, and they said that Tracy was shy and introverted. She had a summer job at the ice cream parlor in Plainsview and she was in the school choir.”

I looked at the photo Heather had printed out. It was a school portrait of Tracy, her hair carefully blow-dried and sprayed. She had put on blush and eye shadow, and it looked weirdly out of place on her young face. “She sounds awesome,” I said sadly.

“I think so, too,” Heather said. “She went to a friend’s house on November 27, and they watched TV and played Uno until eight o’clock. Oh, my God, the eighties. Anyway, Tracy left and got on her bike. Her friend watched her pedal away. She never got home, and at eleven her parents called the police. The cops said they had to wait until morning in case Tracy was just out partying or something.”

I stirred my chicken soup, my stomach turning.

“The cops came and interviewed the parents the next morning, and they started a search. On November 29, Tracy’s body was found in a ditch off Melborn Road, which is between Plainsview and Fell. At the time, Melborn Road was a two-lane stretch that no one ever drove. Now it’s paved over and busy. There’s a Super 8 and a movie theater. It looks nothing like it did in 1982.” She turned the page to show a printout of an old newspaper article. LOCAL GIRL FOUND DEAD was the headline, and beneath it was the subhead Police arrest homeless man.

“A homeless guy?” I asked.

“He had her backpack. He seems to have been a drifter, passing through from one place to another. He had a record of robberies and assaults. The thing is, he actually went to the police to turn in the backpack when he heard the news. They kept him on suspicion, and when he couldn’t provide an alibi for the murder, they charged him.”

“That’s it? They didn’t look at anyone else?”

“It doesn’t seem like it. He said he found her backpack by the side of the road, but who was going to believe him? His fingerprints were all over it, and there was a smear of Tracy’s blood on one of the straps. There were no other suspects. Her parents were beside themselves. They said they’d had a warning that someone had been following Tracy. The whole story fit.” She held up a finger, relishing the story in her Heather way. “But. But.”

“You like this too much,” I said, smiling at her.

“Whatever, Dr. Carly. You’re not listening. The next part gets interesting.”

“Like it wasn’t interesting before. Go ahead.”

“The homeless guy was never convicted. He never even went to trial. It seems that even though he was homeless, he had some kind of access to a good lawyer. Everything was hung up for over a year, and then the charges were dropped and he was set free. The case was opened again, and it’s still open. Tracy’s parents eventually got divorced, but her mother has never given up on solving the case. She started a website for tips on Tracy’s murder in 1999. She still has it, though from what I can tell it’s mostly run by Tracy’s younger brother now. There’s a Facebook page and everything. And remember how I said that someone had been following Tracy? They knew because they got an anonymous letter in the mail the week before she was killed. And now that letter is posted on the Facebook page and the website.” She took a sheet of paper out of her stack and handed it to me.

It was a scan of a handwritten letter. I read it over.

This letter is to warn you that I’ve seen a man following Tracy Waters. He was staring at her while she got on her bike and rode away on Westmount Avenue on November 19 at 2:20 in the afternoon. After she rode away he got in his car and followed her.

I know who he is. I believe he is dangerous. He is about 35 and six feet tall. He works as a traveling salesman. I believe he wants to kill Tracy. Please keep her safe. The police don’t believe me.

Keep her safe.

I pushed my soup away. “This is the saddest letter I’ve ever read in my life,” I said.

“The mother was worried when they got it. The father thought it was a prank. The mother decided that the father must be right. A few days later, Tracy was dead. Hence the eventual divorce, I think.”

“A traveling salesman,” I said, pointing to the words. “Like Simon Hess.”

“Who disappeared right after Tracy was murdered. But if you can believe it, it gets even better.”

I sat back in my seat. “My head is already spinning.”

“Tracy’s mom always felt that the letter was real,” Heather said. “She thought it was truly sent by someone who saw a man following Tracy. And it wasn’t a homeless drifter, either.” She tapped the description of the salesman. “This letter is part of why the case against the homeless guy was eventually dropped. But get this: In 1993, over ten years after the murder, Mrs. Waters got a phone call from Tracy’s former high school principal. He told her that he had a phone call a few days before Tracy’s murder from someone claiming to be another student’s mother. The woman said that she’d seen a man following Tracy, and that she thought the school should look out for her.”

“And he didn’t tell the police?” I said. “He didn’t tell anyone for ten years? Why not?”

“Who knows? He was probably ashamed that he didn’t do anything about it at the time. But he was retired and sick, and he felt the need to get it off his chest. So this was a preventable murder. Someone warned both Tracy’s parents and her principal about it. And if either of them had listened and kept Tracy home, she wouldn’t have died.”

I blinked at her. “A woman,” I said. “The person who called the principal was a woman.” I picked up the scan of the letter and looked at it again. “This could be a woman’s handwriting, but it’s hard to tell.”

“It’s a woman’s,” Heather said. “Tracy’s mother had a handwriting expert analyze it.”

There were too many pieces. They were falling together too fast. And the picture they made didn’t make any sense. Who knew that Tracy was going to be killed? How? It couldn’t possibly be Vivian, could it?

And if Vivian knew that Tracy was going to be murdered, why couldn’t she save herself?

“Did you call Alma?” Heather asked.

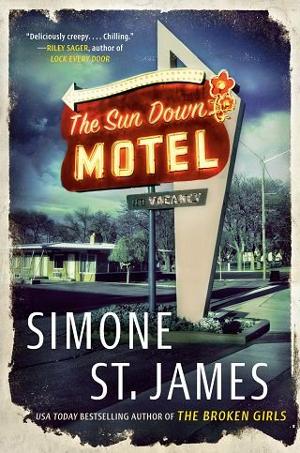

“I sent her a text,” I said. “She said she was a night owl, but it’s still sort of weird to call someone you barely know in the middle of the night when it isn’t an emergency. I’m not even sure she texts, to be honest. If I don’t hear from her this morning, I’ll call her.” I looked at the time on my phone. “I should probably get back to the Sun Down. Not that anyone would know I’ve been gone.”

“Where’s Nick?”

“Off somewhere getting those negatives developed. He said there’s an all-night place in Fell.”

“That would be the ByWay,” Heather said, gathering her papers. “I think they still rent videos, too.”

“Fell is officially the strangest place on Earth.” I looked at Heather as she picked up her coat. “What would you say if I told you the Sun Down was haunted?”

She paused and her eyes came to mine, her eyebrows going up. “For real?”

“For real.”

She watched me closely, biting her lip. Whatever expression was on my face must have convinced her, because she said, “I want to hear everything.”

“I’ll tell you.”

“And I want to see it.”

I rubbed the side of my nose. “I can’t guarantee that. She doesn’t come out on command.”

“She?”

“Betty Graham.”

Heather’s eyes went as wide as saucers. “You’re saying that Betty Graham’s ghost is at the Sun Down.”

“Yeah, I am. Nick has seen her, too.”

“Is she . . . Does she say anything?”

“Not specifically, but I think she’s trying to.” I thought of the desperate look on Betty’s face. “There are others. There’s a kid who hit his head in the pool and died. And a man who died in the front office.”

“What?”

“Keep your voice down.” I waved my hands to shush her. “I know, it’s weird, but I swear I really saw it. Nick is my witness. I didn’t say anything before because it sounded so crazy.”

“Um, hello,” Heather said. She had lowered her voice, and she leaned across the table toward me. “This is big, Carly. I want to stake the place out. I want to get photos. Video.”

I looked at the excited splotches on her cheeks. “Are you sure that would be good for you?”

“I’ve read and seen every version of The Amityville Horror there is. Of course it’s good for me. I’m better with ghosts than I am with real life.”

“This is real life,” I said. “Betty is real. She’s dead, but she feels as real as you and me. And the first night I saw her, there was a man checked in to the motel, except he wasn’t. His room was empty and there was no car. I know—maybe he left. But I keep thinking back to it, and I’m starting to wonder if he didn’t leave at all.”

“If he didn’t leave, then where did he go?”

We looked at each other uncertainly, neither of us able to answer. The door to the diner opened and Nick walked in. He brushed past the dead-eyed truckers and exhausted-looking shift workers without a sideways glance. He had an envelope in his hand.

“Photos,” he said.

He sat on my side of the booth as I scooted over, as if he was already learning to stay out of Heather’s no-touch bubble. He brought the smell of the crisp, cold morning with him, no longer fall but heading for winter. He opened the envelope and dumped the photographs onto the table.

We all leaned in. There were four photos, each of the same subject from a different angle: a barn. It was old, half the roof fallen in. The photos were taken from the outside, first in front, then from farther back, then from partway down a dirt track.

“Why would Marnie take these?” Heather asked.

“Why didn’t she have prints?” Nick added. “Either she never made any, or she made them and gave them to someone.”

“It’s a marker,” I said, looking at the photos one by one. “This barn is important somehow. She wanted a visual record in case she ever needed to find it again.”

We stared at them for a minute. The barn looked a little sinister, its decrepit frame like a mouth missing teeth. The sagging roof was sad, and the front façade, with its firmly shut doors, was blank. It looked like a place where something bad had happened.

“Where do you think it is?” Heather asked.

“Impossible to tell,” I said. “There aren’t any signs. It could be anywhere.” I peered closer. “What do you think this is?”

In the farthest angle, something was visible jutting over the tops of the trees.

“That’s the old TV tower,” Nick said. “It’s gone now. They took it down about ten years ago, I think.”

I looked at him. “But you know where it was?”

“Sure I do.” He was leaned over the table, his blue gaze fixed on the picture. “It’s hard to tell what direction this is taken from, but it can’t be more than a half mile. These farther shots are taken from a driveway. A driveway has to lead to a road.”

I grabbed my coat. “We can go now. The sun’s starting to come up. We have just enough light.”

“Don’t you have to be at work?” Heather asked.

“They can fire me. I came to Fell for this, remember? This is all I want.”

“But we don’t know what this is,” she said, pointing to the pictures.

I looked at the pictures again. “It’s the key.” I pointed to the barn. “If Marnie wanted to be able to find that barn again, it’s because there’s something inside it. Something she might want to access again.”

“Or something she might want to direct someone else to,” Nick added.

I looked at both of them, then said the words we were all thinking. “What if it’s a body? What if it’s Vivian’s body? What if that’s what’s in the barn?”

We were quiet for a second and then Nick picked the photos up again. “We’ll find it,” he said. “With these, it’ll be easy.”

• • •It took us until seven. By then the sun was slowly emerging over the horizon, hidden by a bank of gray clouds. All three of us were in Nick’s truck. We’d circled the area where the TV tower used to be, driving down the back roads. We were on a two-lane road to the north of the old tower site, looking for any likely dirt driveways.

“There,” I said.

A chain-link fence had been put up since the photos were taken, though it was bent and bowed in places, rusting and unkempt. A faded sign said NO TRESPASSERS. Behind the fence, a dirt driveway stretched away. I dug out one of Marnie’s pictures and held it up.

The trees were bigger now, but otherwise it looked like the place.

Nick turned the engine off and got out of the truck. Heather and I got out and watched him pace up the fence one way, then the other. Then he gripped the fence and climbed it, launching himself over the top. His feet hit the ground on the other side and he disappeared into the trees.

He reappeared ten minutes later. “The barn is there,” he said. “This is the place. There’s no one around that I can see—there hasn’t been anyone here in years. Come over.”

Heather climbed the fence first. I boosted her over and Nick helped her down. Then I climbed, waiting every second for a shout, the bark of a dog, the scream of an alarm. There was only silence. I swung my leg over and Nick took my waist in his hard grip, lowering me down.

“This way,” he said.

The foliage had grown in over the years, and we fought our way through the naked branches of bushes until we found the path of the driveway. It was overgrown, too, washed over with years of snow and rain. There were no tire tracks. I could see no evidence of human habitation at all. The wind blew harsh and cold, making sounds in the bare branches of the trees.

“What is this place?” I asked.

“I have no idea,” Heather said. She was walking as close to me as she could, her cheeks deep red with cold. “It looks like someone’s abandoned property.”

How old were Marnie’s photos, I wondered? If they had been taken at the same time as the Sun Down pictures, they were thirty-five years old. Had no one really been here for thirty-five years? Why not?

We picked our way over the uneven drive, and the barn appeared through the trees. It wasn’t even a barn anymore; it was a wreck of broken boards, caved in and rotted. There were dark gaps big enough to let a full-grown man through them. The front doors looked to be latched closed, but with the state of the rest of the walls, it wasn’t much security.

“Wait here,” Nick said. He circled the barn, disappearing around the corner. We heard the groan of rotten wood snapping. “I found a way in,” he called.

On the side of the barn, we found he’d snapped some rotten boards and opened the hole wider for us. He looked out at us. “It’s dark in here, but I can see something.”

I looked at Heather. She had gone pale, her expression flat. Gone was the girl who had wanted to spend the night at the Sun Down, taking pictures and videos of ghosts. I didn’t have to touch her to know that her skin would be ice-cold. “You don’t have to come in,” I said.

She looked at me, her gaze skittish as if she’d almost forgotten I was there. “I should go in.”

I stepped closer to her. “This isn’t a contest. You don’t win a prize for going in there. She’s my aunt, not yours. This is my thing. Just wait and I’ll tell you if it’s safe.”

I thought she’d argue with me, but instead she hesitated, then gave a brief nod. I wanted to touch the arm of her coat, but I didn’t. Instead I turned back to the barn.

The hole gaped at me, deep black. I could see nothing inside, not Nick, not even a shadow. A dusty, dry, moldy smell came from the hole, and dust motes from the disturbance swirled in the air.

“Carly?” Nick called from the dark.

Down the rabbit hole, I thought, and stepped through.

The light inside came through the gaps in the walls, soft slices of illumination from the gray sky overhead. I could see the four walls, junk tossed against them, dark shapes in the corners. An old bicycle, tools, scattered garbage. As my eyes adjusted to the dark I caught sight of Nick, who had walked to the other end of the barn. He was standing right behind the closed doors. He turned and looked at me. “Hey.”

I came closer to him. Behind him was an old green tarp thrown over what was obviously a car underneath. I paused at Nick’s shoulder, looking at it.

My mind spun. The newspaper reports had said that Viv’s car was left in the Sun Down parking lot the night she disappeared. Wherever she’d gone, she hadn’t taken it.

But what had happened to her car after the investigation? Where had it gone? Where did a missing person’s car go, long after they went missing?

“Uncover it,” I whispered to Nick.

He didn’t hesitate. He grabbed one end of the tarp and tugged it, stepping back and letting it fall to the dirty floor. Underneath it was a car, boxy and decades old. The color was indistinguishable in the dim light. The tires were flat. The windows were opaque with dust.

Nick stepped over the tarp and brushed the side of his hand along the passenger window, smearing the dust. “No one’s been near this thing in ages, maybe years,” he said. He leaned forward and peered through the clear hole he’d made.

Don’t, I wanted to shout. Don’t. I jumped at the sound of flapping in one of the barn’s upper corners, cold sweat rising between my shoulder blades as I realized it was a bird somewhere up there in the shadows. I made my feet move, made myself circle the car to the driver’s side and wipe my own spot, peer through it.

The driver’s seat was empty, tidy. I straightened and tried the door handle. It opened, the click loud in the silence. Inhaling a breath, I pulled the door open.

A rush of stale air came out at me, laced with something sour. Dust motes swirled in the air. On the passenger side, Nick opened the door and leaned in. We both craned our necks, peering around the empty car.

Nothing. No dead body. No sign of Viv—no clothing, no nothing. There was no indication that anyone had ever used this car at all. Nick opened the glove box, revealing that it was completely empty.

“Cleaned out,” he said.

“Maybe it’s nothing,” I said. “Maybe it’s just a coincidence. It’s some old car that someone didn’t want to use anymore, and they parked it here and left it. It happens all the time, right?”

“Why did Marnie have photos of this barn, then?”

It didn’t feel right. My stomach was turning, my head pounding. “Maybe Viv stole the car,” I said. “Maybe she stole it and stashed it.”

“Maybe whoever killed her stashed it,” he countered.

“We don’t know that. We don’t know anything.” I sighed. “This is a crazy dead end. We’ve done all this work, and we aren’t any further along than we were. It’s a red herring, Nick.”

“What’s that smell?” he asked.

There was definitely a smell. Sour and rotten, but old. “Garbage?”

“Worse than garbage.” He straightened and stepped back, leaving the front passenger door open. He opened the back passenger door and peered in. “Nothing back here. But the smell is worse.” He straightened again, leaving that door open, too.

We walked to the back of the car. The trunk had a keyhole in it, the way all old cars did. We’d seen no sign of a key.

“How do we get that open?” I asked as Nick bent his knees, lowering himself to a crouch.

“We don’t open it,” he answered me. “We call the cops.” He pointed to the floor beneath the trunk. “Either that’s oil or it’s very old blood.”

I crouched and followed where he was pointing. There was a large pool of something black beneath the trunk. It was dry and very, very old.

The blood rushed from my head, and for a second I thought I would faint. The pool was definitely too big to be oil. I gripped my knees and tears came to my eyes, too swift and hard for me to stop them. “Viv,” I said. I started shaking. My aunt was in the trunk, her body a foot from me, behind metal and cloth. She was dead in this car. She had been here for thirty-five years, her blood pooling, then drying and darkening on the floor. So lonely and silent. I inhaled a breath and a sob came out. “He killed her,” I said, my voice choked. “He did it. He killed those others. He killed Viv.”

I felt a hand on the back of my neck—large, warm, and strong. “You’ve got this, Carly,” he said gently. “You’ve got it.”

I inhaled again, because I couldn’t breathe. Another sob escaped my throat. My cheeks were soaked with tears now, my lashes wet, getting water on my glasses. “I’m sorry,” I managed as I cried. “I didn’t—I didn’t expect—”

“I know,” he said.

I’d been so in control. I’d been able to handle everything—ghosts, mysteries, this strange and crazy place. It wasn’t a game, exactly, but it was a project. A quest for justice. A thing I had to do in order to get on with my life. And if I did it, I would be fine again. I would know.

I hadn’t expected that being at Vivian’s grave would break my heart. I hadn’t expected the grief. It was for Viv, and it was for my mother, who had lived the last thirty-five years of her life not knowing this car was here, that her sister’s body was alone and silent in the trunk. My mother had lived three and a half decades with grief so deep and so painful she had never spoken about it. She’d died with that grief, and now she would never feel any better.

I sobbed into my dirty hands, crouched on the floor of the barn. I cried for Viv, who had been so beautiful and alive. I cried for the others—Betty, Cathy, Victoria. It was over for them, too. I cried for my mother and for me.

Nick moved closer, put his arm around my shoulders. He knew exactly how I felt—of course he did. He knew how this kind of thing rips you in pieces from the inside out, changes the makeup of who you are. He was the only person who could be here and actually understand. He held his arm around my shoulders and let me weep. He didn’t speak.

After a minute I heard Heather’s voice from the other end of the barn. “What’s going on?”

“There’s a car,” Nick called to her, his voice calm. “There’s old blood pooled under it. We think there’s a body in the trunk. Can you call the cops?”

Heather didn’t say anything, and I assumed she’d stepped back out to pull her phone out of her pocket. I wiped my eyes and mopped the snot on my face, attempting to get a grip.

“I’m okay,” I said.

“We should go,” Nick said quietly. “This is a crime scene.”

He was right. Thirty-five years old or not, this was the site of my aunt’s dumped body. We needed to get our footprints and our fingers and our hair fibers out of here. Even the rankest amateur knew that, let alone a true-crime hobbyist like me.

I straightened, Nick keeping his hand on my elbow to help me keep balance. He’d know all about crime scenes, since his childhood house had been one. Nick had real-life experience of crime instead of just in books and on the Internet. Well, now I had experience, too.

Vivian was dead. But Simon Hess had been at the Sun Down. He’d seen Viv. And he’d disappeared at the same time. I knew now what had happened to Vivian, and I knew who had done it. My next job was to track down Simon Hess, wherever he was, and make him pay.

• • •It was past noon when a cop came out of the barn and down the drive to where I was standing. The gates to the rusty fence were thrown open now and the dead foliage had been crushed with tire tracks. A single uniformed officer had been sent out first, and then a short stream of vans and unmarked cars had arrived. We had been shooed off the property from the first, and we hadn’t been able to see anything that was going on. We’d been questioned, together and separately, over and over. It was freezing and damp. When the cops finished with us, Nick had driven Heather home because she was nearly shaking with cold and shock. I hadn’t been able to leave. Not until someone told me something—anything.

In my pocket was a photo. One of the pictures from Marnie’s stack, showing Simon Hess’s car parked at the Sun Down. It was exactly the same make and model as the car we’d seen in the barn. The size and shape were burned into my mind, and I knew, in my heart, that we’d found Simon Hess’s car.

Nick came back in his truck, bringing me hot coffee and something to eat. I’d sipped the coffee and forgotten the food. My phone was long dead. I stood on the dirt road, as close to the gates as the cops would allow, simply waiting. I was going to wait for as long as it took.

The police knew my situation, that I was looking for my aunt who had vanished in 1982. After a while someone inside the barn must have taken pity on me, because a man came down the dirt drive to the gate. He was about fifty, a black man with close-cropped graying hair. He was wearing jeans and a thick black bomber jacket, which meant he wasn’t a uniformed officer. I had no idea who he was. His face was stern, but when he looked at me I knew he had seen people like me before, desperate family members waiting for any word at all.

“Are you Miss Kirk?” he asked me.

“Yes.”

He introduced himself—garbled a name and a title that I didn’t hear or retain. The blood was rushing too loudly in my ears.

“I understand you’re looking for your aunt, Vivian Delaney,” the man said.

I nodded.

He looked at me closely. “Listen to me, okay? I understand you’re in a weird place. But listen to what I’m saying.”

He did know. He understood what it felt like. I felt my shoulders relax, just a little.

“Two things,” the man said. “There is a body in that car. It’s been there a long time.”

My fingernails dug into my palms. I barely felt it.

“The second thing,” the man said, “is that it isn’t your aunt.”

My lips were numb, barely working. “How do—how do you know?”

“Because it’s a man,” he said. He shook his head as I opened my mouth again. “No. I’ve got nothing else to say. We’re conducting an investigation, and I have no information yet. But I can tell you definitively that we do not have Vivian Delaney in there. I’m sorry for the loss of your aunt. But we have your contact information if we need you, and you need to go home.”

He waited, his eyes on mine, until I’d nodded a brief assent before he turned his gaze to Nick. “Make sure she gets home,” he said, underscoring the message. Then he turned and walked away.

My head was spinning, my brain feverish. Nick took my elbow again and led me back to his truck. He helped me in, then circled to the driver’s side, getting in and slamming the door.

He turned the key and the truck’s heater came on, a blast of warm air on my face. My cheeks and lips tingled as the cold left them. I flexed my frozen fingers.

Nick didn’t put the truck in gear. He just sat there, his dark eyes on me, his expression unreadable. He was wearing a coat, but once again he didn’t seem cold. I thought he must be like a human furnace, not to be cold after all these hours. I wondered what that was like.

“Carly,” he said.

“It’s Simon Hess,” I said.

His eyes narrowed and he didn’t speak.

“I thought he was a monster,” I said, more easily now that my face was thawing. My brain thawing, too. Everything was thawing. “I thought he killed her and got away with it. But he didn’t, did he?”

“No,” he said. “He didn’t get away with it. At least, not in the end.”

I scrubbed a hand over my cheek, beneath the rim of my glasses. My cheek was starting to feel warm now. I was light-headed from the shock and the crying and the coffee and the lack of food. But at the same time I was thinking more clearly than maybe I ever had.

“It doesn’t answer the question of Vivian,” Nick said. “Where is she?”

And I knew. I simply knew. I didn’t know everything that had happened, and I didn’t know all of the details, but I knew. Because after all this time, living this life here in Fell, I was her.

I looked at Nick, right into his blue eyes, and said, “I think my aunt Viv did a very, very bad thing.”

Fullepub

Fullepub