Carly

Fell, New York

November 2017

CARLY

The house on German Street was at least sixty years old, a post–World War II bungalow with white wood siding and a roof of dark green shingles. This was a residential street in downtown Fell, a few blocks from Fell College in one direction and the huge Duane Reade in the other. In this small knot of streets, everything had been tried at one point or another: low-rise rental apartment buildings, corner stores, laundromats, a small medical building advertising physiotherapists and massage. In between these were the small houses like this one, the remnants of the original neighborhood that had been picked apart over the decades. This one was well kept, with hostas planted along the front and in the shade beneath the large trees, a fall wreath of woven branches hanging on the door.

There was a car in the driveway. That was a good sign, because Heather and I were dropping in unexpectedly.

“You’re up for this?” I asked Heather for the third time.

She gave me a thumbs-up, and we got out of the car.

We could hear the doorbell chime through the door. After a minute the door opened and a woman appeared. She was black, in her fifties, with gray hair cropped close to her head. She wore a black sweater, black leggings, and white slippers.

Her eyes narrowed at us suspiciously. “Help you?”

“Mrs. Clark?” I said. “I’m Carly Kirk. We talked on the phone.”

“The girl asking me about the photograph,” Marnie said. “I already told you I have nothing to say.”

“This is my friend Heather,” I said. “We just have a few questions. We’ll be quick, I promise.”

Marnie leaned on the door frame, still not stepping aside. “You’re persistent.”

“Vivian was my aunt,” I said. “They never found her body.”

Marnie looked away. Then she looked from me to Heather and back again. “Fine. I don’t know how I can help, but you get a few minutes. My husband is home in half an hour.”

She led us into the front living room, a well-lived-in space with a sofa, an easy chair, and a big TV. A shelf of photos showed Marnie, her husband, and two kids, a son and a daughter, both of them grown. Heather and I sat on the sofa and Marnie took the easy chair. She didn’t offer us a drink.

“Listen,” she said. “I told you that photo was just something I got paid for. I don’t know anything about your aunt disappearing all those years ago.”

Heather pulled a printout of the article about Vivian from her pocket and unfolded it. There was Marnie’s photo, Vivian with her lovely face and curled hairdo, her head turned and her expression serious. “Do you remember taking this?” Heather asked her.

Marnie glanced at it and shook her head. “I was a freelance photographer in those days. I shot anything that would pay. I took pictures of houses for real estate agents. I did portraits. I worked for the cops a few times, taking shots of burglary scenes.” She put her hands on the arms of the easy chair. “When I met my husband, I took a job with the studio that worked for the school board. I did class photos. It didn’t pay a whole lot, but the hours were easy and I had my son on the way. I couldn’t run around taking pictures at all hours anymore.”

“You said on the phone you’ve lived in Fell all your life,” I said.

“That’s right.”

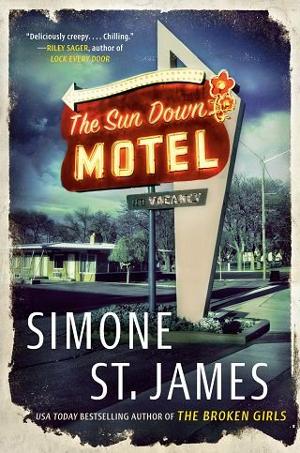

“Do you know the Sun Down Motel?”

Marnie shrugged. “I suppose.”

“Here’s the thing,” Heather said. “I took this photo and enlarged it. You see this in the corner here.” She pointed to the corner of the photo of Vivian. “When the picture is enlarged, that’s a number—actually, it’s two numbers, a one and a zero. Like the numbers on the front of a motel room door.” She pulled out her phone. “So I went to the Sun Down and looked at their room numbers. The rooms on the bottom level all start with a one, and the rooms on the upper level all start with a two. And the door numbers look exactly like the numbers in your picture.”

Marnie had gone still, her gaze flat. “What exactly are you saying?”

“The Sun Down hasn’t changed its door numbers since it opened,” I said. “This picture”—I pointed to the photo of Viv—“the one you took, was taken at the Sun Down Motel. Do you remember why you were taking pictures there?”

Marnie barely glanced at the photo. She shook her head. “What do you think is going to come from this?” she asked, looking from me to Heather and back. “Nancy Drew One and Nancy Drew Two. Do you think you’re going to catch a murderer? Tackle him down and tie his hands while the other one calls 911? Do you think some photo pulled out of a thirty-five-year-old newspaper is going to be the smoking gun? Real life doesn’t work that way. I’ve seen enough of it to know. Gone is gone, like I told you on the phone. I look at you two and wonder if I was ever as young as you are. And you know, I don’t think I ever was.”

Her dark brown eyes looked at mine, and I held her gaze. We locked there for a long second.

“You took pictures at the Sun Down in 1982,” I said. “Tell me why.”

Still she held my gaze, and then she sighed. Her shoulders sagged a little. “I took a side job for a lawyer. Following his client’s wife. I followed her around and took pictures for evidence. She was cheating on him, just like he thought, and she met the other man at the Sun Down. So the pictures I took were not exactly for public use.” She leaned back in her chair. “That job paid me a hundred and seventy-five dollars, and I paid the utility bill for almost a year with it. I was on my own back then, paying for myself. I needed the money.”

I felt a tickle of excitement in the back of my mind. “What was the client’s name?” I asked.

“Bannister, but it was thirty-five years ago. They might both be dead by now, for all I know.”

“So you were taking pictures at the Sun Down while Vivian was there. Did you ever talk to her?” I asked.

“I had no reason to talk to her,” was the reply. “I was in my car in the parking lot. I wasn’t really advertising myself.”

Which wasn’t an answer. “So you didn’t meet her?”

“Did I go in and introduce myself to the night shift clerk while I was following someone? No.”

“You knew what she looked like,” Heather chimed in. “When she disappeared, you knew you had a photo of her and you offered it to the newspapers.”

“I knew what she looked like because her picture was already in the papers,” Marnie corrected her. “When I saw her face, she looked familiar. The articles said the Sun Down, so I checked my photos and I saw the same face.”

“Where are those photos now?” I asked her.

Marnie looked at me. “You think I kept photos from 1982?”

I looked at my roommate. “Heather, do you think she kept photos from 1982?”

“Let’s see,” Heather said. “A divorce case, valuable pictures that could be used as blackmail. I’d keep them.”

“Me, too, especially if there was a known murder victim in them. You might be able to sell the pictures all over again if her body is found.”

“Double the money,” Heather agreed.

“You two are a piece of work,” Marnie said. “I ought to smack both of you upside the head.” She lifted herself out of the chair and left the room.

We waited, quiet. I didn’t look at Heather. When I heard the sounds of Marnie rustling through a closet in the next room, I tried not to smile.

She came back out with a stack of pictures in her hand, bound together by a rubber band. She tossed the stack in my lap. “Knock yourselves out,” she said. “The last time I looked at those was 1982, and they weren’t very interesting then. I doubt they’re any more interesting now. If you think your aunt’s killer is in there, you can do the work yourself.”

I picked up the stack. It looked like a hundred or so pictures. “Has anyone else seen these?”

“The lawyer I worked for back then got copies. I kept my copy just in case, for insurance. I even kept the negatives—you can have those, too.” She dropped an envelope on top of the photos. “Like you said. When I sold the picture of Vivian to the newspapers, the cops didn’t even call me. They didn’t come to my door asking for that stack. So no, no one else has seen them.”

We thanked her and left. When we got into the car and slammed the doors I said to Heather, “Okay, how many lies did she tell, do you think?”

“Three big ones and a bunch of little ones,” she said without a pause.

I thought it over. “I missed a few. Tell me the ones you know.”

She put up an index finger. “One, someone else has definitely seen the photos. They were the last known photos of a missing person. The cops must have at least looked at them, though I don’t know why she’d lie.”

I nodded.

“Two”—Heather put up a second finger—“her old client, Bannister, is definitely not dead. She was trying to discourage us from finding him.”

“I caught that one,” I said.

“And three . . .” Heather opened her file of newspaper clippings. “I’ve seen every mention of Vivian’s disappearance in every paper. The first mention of it on the first day was a paragraph of text.” She pointed to a few sentences in the Fell Daily. “It just says that local girl Vivian Delaney is thought to be missing, blah blah. Call the police if you know anything. There’s no picture. But the next day, Marnie’s photo runs in the paper. Which means Marnie didn’t match the name and the photo to the girl from the Sun Down. When she sold her photo to the papers, she knew Vivian’s name and her face.”

“So she didn’t just sit in the parking lot,” I said.

“No.” Heather snapped her file shut. “She knew Vivian, and she isn’t admitting it. What I want to know is why.”

Fullepub

Fullepub