Viv

Fell, New York

October 1982

VIV

There was a diner called the Turnabout on a stretch of the North Edge Road, close to the turnoff for the interstate. It was on the outskirts, when you were in the territory of overnight drivers and truckers, where you could find a place that was open until midnight.

The Turnabout wasn’t a fancy place, and the coffee wasn’t particularly good, but Viv found that she didn’t mind it. For three dollars she could get a meal, and there were people here—real people who knew each other, who sometimes sat around and talked. She’d forgotten what it was like to be around people who weren’t just passing through.

Tonight she sat in a booth and waited, fidgety and impatient. She had her notebook and pen with her, along with a manila folder stuffed with papers. She’d spent a week gathering everything, and tonight she would find out if she’d wasted her time.

You can’t do this.

Yes, you can.

To say it was a rabbit hole was an understatement. Ever since Jenny, her roommate, had made those comments about Cathy Caldwell and Victoria Lee, Viv had felt an uncomfortable itch, a need to know. It felt like curiosity mixed with something lurid and mysterious, but Viv knew it was deeper than that. It felt almost like a purpose. Something she was meant to find.

She’d left the apartment early every day and gone to the Fell Central Library, digging through old newspapers. It wasn’t hard to find articles about Cathy and Victoria; their murders had made the news. After a week each girl had dropped off the front page of the Fell Daily, and then you had to find updates—what few there were—in the back pages, with headlines like POLICE STILL MAKE NO HEADWAY and QUESTIONS STILL REMAIN.

The waitress poured Viv another coffee, and Viv anxiously glanced at the door. Because Alma Trent had said she’d come.

She did. She came through the door five minutes later, wearing her uniform and nodding politely at the waitress. “How are things, Laura?”

“Not so bad,” the waitress said. “You haven’t been here in a dog’s age.”

“You haven’t had to call me,” Alma said practically. “But I’d sure like a cup of coffee.” She slid into the booth opposite Viv. “Hello, Vivian.”

Viv nodded. Her palms were sweating, but she was determined not to be the speechless idiot Alma had met before. “Thanks for coming,” she said.

“Well, you said you had something interesting for me.” Alma glanced at her watch. “I’m due on shift in forty-five minutes, and if I’m not mistaken, so are you.”

Viv put her shoulders back. She was wearing a floral blouse tonight, and she’d put on a yellow sweater over it. She’d considered wearing darker colors to make herself look more serious, but she liked the yellow better. “I wanted to talk to you about something. Something I think that could help you.”

“Okay,” Alma said politely, accepting a cup of coffee from the waitress and stirring some sugar into it.

“It’s about Cathy Caldwell and Victoria Lee.”

Alma went very still.

Viv opened her folder. “Well, it isn’t only about them. It’s—just listen, okay?”

“Vivian.” Alma’s voice was almost gentle. “I’m only the night-shift duty officer. I don’t work murder cases.”

“Just listen,” Viv said again, and there must have been something urgent in her voice, something that was almost alarming, because Alma closed her mouth and nodded.

“Cathy Caldwell was killed in December 1980,” Viv said. “She was twenty-one. She worked as a receptionist at a dental office. She was married and had a six-month-old son. Her husband was deployed in the military.”

She knew all of these things. She recited them like they were the facts of her own life. Alma nodded. “I remember it.”

“She went to work one day and left her son with a babysitter. She called the babysitter at five o’clock and said she was picking up groceries on the way home, that she’d be fifteen minutes late. At six thirty, the babysitter called her mother, asking what she should do because Cathy wasn’t home yet. The mother said she should wait another hour, then call the police. So at seven thirty, the babysitter called the police.” She looked at Alma, then continued. “The police searched for her for three days. They found her body under an overpass. She was naked and had been stabbed in the side of the neck three times. The stabs were deep. They think he was trying to get her artery. Which he did.”

“Vivian, honey,” Alma said. “Maybe you shouldn’t—”

“Just listen.” She had to get this out. It had been boiling in her mind for days as she scribbled thoughts into her notebook. Alma quieted and Viv pulled a hand-drawn map from her file folder.

“The article said that Cathy’s usual grocery store was this one here.” She pointed to a spot on the map, halfway between the X marked with Cathy’s work and the X marked with Cathy’s home. “No one saw her there that night. Her car was found just out of town, parked at the mall, so there was a theory she went shopping instead. But that wasn’t like Cathy at all. And you see, it makes sense. Because he dumped her at the overpass, here”—she indicated another X—“and then he drove her car to the mall, which was ten minutes away. Just because her car was there doesn’t mean she was ever there.”

“I get it,” Alma said. “You’ve been playing amateur detective.”

The words stung. Playing amateur detective. It didn’t feel like that. “I’m getting to a point,” Viv said, but Alma kept talking.

“We get people like this sometimes,” Alma said. “They call in to the station with their theories. Especially when it comes to Cathy. People don’t like that it wasn’t solved. They feel like her killer is out there somewhere.”

“That’s because he is,” Viv said.

Alma shook her head. “I didn’t work that case, but I was on the force when it happened. We all got briefed. The leads were all followed.”

Viv was losing Alma, she could tell. “Just hear me out this one time,” she said. “Just until you have to go on shift. Then you’ll never hear from me again.”

Alma sighed. “I hope I hear from you again, because I like you,” she said. “You seem like a bright girl. All right, I’ll drink my coffee and listen. Carry on.”

Viv took a breath. “There was a theory about Cathy. They found that one of her tires had a repaired puncture in it. So he could have punctured her tire, then taken her when he pulled over to help her. But the article said they couldn’t determine when the puncture repair was done.” She flipped a page to another set of neatly written notes. “I used the Fell yellow pages and called every auto repair shop. They all said they had no record of fixing Cathy’s tire. But it was two years ago now, so it’s possible she came in and the record is long gone.”

There was silence, and Viv looked up to see Alma looking at her. “You called auto repair shops,” Alma said. It wasn’t spoken as a question.

Viv shrugged like it was no big deal. She wasn’t about to admit that she’d been hung up on three times. “I just asked a few questions. The other thing is that if Cathy was stabbed in the neck she would have lost a lot of blood. Like, gallons. And the articles didn’t say there were gallons of blood under the overpass.”

Alma’s eyebrows went up. “So you surmise that she was killed elsewhere.”

“I looked up the weather records,” Viv said, ignoring Alma’s dry tone. “There was a thunderstorm with heavy rain the day after Cathy disappeared. So he could have killed her outside somewhere, and the rain washed the blood away.” She ran a hand through her newly short hair. “If you were going to kill someone with a lot of blood, where would you do it? Not the overpass, for sure. There are cars going by there. My guess is the creek.” She pointed to the creek on her map, the bank two hundred yards from the overpass. “None of the articles say if they checked the creek. Or if Cathy had mud on her. I bet that’s in the police records, though. If Cathy was muddy.”

“You looked up weather records, too?”

“Sure,” Viv said. “They’re right there in the library.” She flipped to another page in her notebook. “Personally, I think the tire puncture is a coincidence. If he didn’t get her on the side of the road, and he didn’t get her at the grocery store, then that leaves one place.” She pointed to an X on the map. “Cathy’s work. He got her when she got into her car.”

Alma sipped her coffee. She seemed to be getting into it now. “It’s a theory, sure. But so far you aren’t telling me anything I don’t already know, or anything I can’t look up at work.”

“Victoria Lee,” Viv said, ignoring her and flipping to yet another page, pulling out another hand-drawn map. “She was eighteen. The article said she’d had ‘numerous boyfriends.’ That means everyone thought she was a slut, right?”

Alma pressed her lips together and said nothing.

“It does,” Viv said. “Victoria had an on-again, off-again boyfriend. They fought all the time. She fought with her parents, her teachers. She had a brother who ran away from home and never came back.” That was almost all she knew about Victoria. There had been considerably less coverage of her in the newspapers next to pretty, upstanding young mother Cathy. After all, Victoria’s killer had been arrested. And next to Cathy, Victoria was a girl who deserved it.

“August of 1981,” Alma said, breaking into Viv’s thoughts. “I remember that day well.”

Viv looked up at her and nodded. “Victoria liked to go jogging. She left home here”—an X on the map—“and went to the jogging trail here.” Another X. “She didn’t come home. Her parents didn’t report it until late the next afternoon. They said that Victoria went out a lot without telling them. They figured she found some of her friends.”

“We spun our wheels for a while,” Alma admitted. “The parents were so certain she’d been out partying the night before. So we started there, questioning all her friends, trying to figure out what party she was at. It was a full day before we realized the parents just assumed, and Victoria wasn’t at a party at all. We had to backtrack to the last time anyone had seen her, which was heading to the jogging trail.”

Viv leaned forward. None of this was in the newspapers, none. “The article said they used tracking dogs.”

“We did. We gave them a shirt of hers, and we found her. She was twenty feet off the jogging trail, in the bushes.” Alma blinked and looked away, her hands squeezing her coffee cup. “The coroner said she’d been dead almost the whole time. She got to that jogging trail and he just killed her right away and dumped her. And she just lay there while everyone screwed around.”

They were silent for a minute.

“Was it really her boyfriend?” Viv asked.

“Sure,” Alma said. “They’d had a big fight. She nagged him a lot, and he called her a bitch. There were a dozen witnesses. Then Victoria went home and fought with her parents, too. The boyfriend, Charlie, had no alibi. He said he went home after their fight, but his mother said he came home an hour later than he claimed he did. Plenty of time to kill Victoria. He couldn’t say where he was. He eventually tried to claim he’d spent that hour with another girl, but he couldn’t produce the actual girl or give her name. The whole thing stunk, and he was convicted.” She frowned. “Why are you interested in Victoria? It isn’t like Cathy. It’s solved.”

Viv tapped her fingers on her notebook. She couldn’t say, really. The papers had portrayed it as an open-and-shut case. But it was those words Jenny had said: Don’t go on the jogging trail. Words of wisdom from one girl to another. Like it could happen again.

“They were so close together,” she said to Alma. “Cathy in December of 1980, Victoria in August of 1981. Two girls murdered in Fell in under a year. Maybe it wasn’t the boyfriend.”

This earned her a smile—kind, but still condescending. “Honey, the police and the courts decide that. They did their job already.”

The court. Was there a transcript of the trial? Viv wondered. How could she get one? “It doesn’t feel finished,” she said, though she knew it sounded lame said out loud. “Why the jogging trail? Why there of all places? He knew her. He could have killed her anywhere. He could have phoned her and lured her somewhere private, say he wanted to apologize or something. And she’d go. Instead he killed her where anyone could walk by.”

“Who knows why?” Alma said. “It was a frequented spot, but it was raining that day. He was angry and irrational. He killed her quickly, dumped her in the bushes, and went home. You’re young, Vivian, but it’s an old story. Trust me.” Alma set her empty coffee cup on the table and gentled her voice. “You’re a nice girl, but you aren’t trained for this kind of thing. I don’t know why you think it’s connected to Cathy. Is that what you’re getting at?”

She couldn’t have said. Because they were both cautionary tales, maybe. Don’t be like her. Don’t end up like her. It was a gut feeling. Which was stupid, because she was just a clueless girl, not a cop or a judge. She had no area of expertise.

Except being a potential victim. That was her area of expertise.

“There weren’t two murders,” Viv said. “There were three.”

She pulled a newspaper clipping from her file and put it in front of Alma. Local family still search for their daughter’s killer, the headline read.

“Betty Graham was murdered, too,” Viv said.

Alma looked at the article, and for the first time her expression went hard. “I’m not going to talk about Betty Graham,” she said. “I shouldn’t be talking to you at all.”

This was why she had done all this research. This was what mattered. To Viv, it was all about the woman in the flowered dress. Who, she now knew, was Betty Graham.

“Betty was unsolved,” Viv said, pushing her. “Before Cathy. In November of 1978.”

Alma’s face was fully shut down now. She shook her head. “That’s what this is all about, isn’t it? I get it now. You heard about Betty and where her body was dumped. That’s what set all of this off.”

“A schoolteacher,” Viv said. “Killed and dumped. The articles say her body was ‘violated.’ What does that mean? Does that mean rape? They didn’t say Cathy was violated.”

“Vivian, this isn’t healthy. These kinds of topics aren’t normal. A nice girl like you, you should be thinking about—”

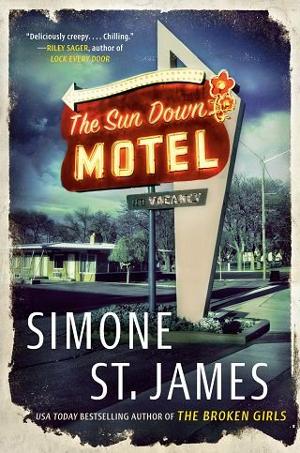

“Parties? Boys? Movies? Cathy and Victoria cared about those things, I bet. Betty, too, maybe.” She tapped the article sitting between them. “Her body was dumped at the Sun Down Motel.”

Alma’s voice was tight. “It wasn’t the Sun Down Motel. Not then.”

“No, it was a construction site. He killed her and dumped her body on a dirt heap at a construction site.”

“It was years ago.”

Maybe, but Betty is still there. She’s still at the Sun Down. I’ve seen her, because she never left.

She’s still there, and she’s telling me to run.

Betty had been twenty-four. Unmarried with no boyfriends, no enemies, no wild habits. Gone from her own house in the middle of a Saturday, never seen alive again. Betty’s parents were still grieving, still looking. “We just want to know who would do such a thing,” Betty’s father was quoted in the article as saying. “We can’t understand it. I suppose it won’t help in the end. But we just want to know.”

The photo of Betty was of the woman she’d seen at the Sun Down. Her hair was tied back and there was a smile on her face for the camera, but it was her.

“What does ‘violated’ mean?” Viv asked again.

Alma shook her head. “You should drop this, honey. These are dark things. They aren’t good for you.”

“Dark things are real things,” Viv said. She’d sat reading articles in the Fell library, her stomach sick. She’d gone home and wept soundlessly on her bed, the sobs coming as drowning gasps, thinking about the woman in the flowered dress, how she was still there where her body was dumped, as if she couldn’t leave. “Listen,” she said to Alma yet again. They were both due on shift in ten minutes. “The last person to see Betty alive was a neighbor who saw what she thought was a traveling salesman knock on Betty’s door. She opened the door and let him in.” Her blood pounded so hard in her temples that she heard her own voice like an echo. “There’s a traveling salesman who comes to the motel. He uses fake names every time he checks in.”

That made Alma go still for a minute as she thought it over—but only for a minute. “So you’ve seen a traveling salesman, and you think it could be Betty’s killer?”

“A traveling salesman who comes to the Sun Down, where her body was left. And doesn’t say who he is.”

“Okay.” Alma looked at her watch. “Look, I’ll tell you what: Get me something, anything I can look up, and I’ll look it up for you. Hell, no one gives a shit what I do on my shift anyway. Next time this guy comes in, get me something. Try to get a name, make and model of car, a license plate, the company where he works, anything. Chat him up a bit. Be nice, but be careful. You’re a good-looking girl and not everyone is as nice as you are.”

“I know.” She knew that now.

“Okay then, we have a deal. I have to go to work now. See you later, Vivian. And if nothing comes of this—please drop it. If not for yourself, then for me.”

Viv nodded, though she knew she would never drop it. It was in her blood now. She gathered her papers and notebook and went to work.

There was no one in the office again, though the lights were on and the door was unlocked. She put on her uniform vest and sat at the desk.

Next time this guy comes in, get me something.

She hadn’t told Alma about the ghosts. About the woman in the flowered dress. About the fact that every time the traveling salesman checked in, the motel woke up and became a kind of waking nightmare.

As if the Sun Down didn’t like him at all.

Next time this guy comes in, get me something.

Run.

Maybe it was nothing. It was probably nothing, and she was just a stupid girl who didn’t know what she was talking about.

“Betty?” she said aloud into the silence.

There was no answer. But when she breathed in, Viv caught a faint trace of fresh cigarette smoke.

What does “violated” mean?

The man in the car, his hand on her thigh.

What does “violated” mean?

Get me something.

Betty, then Cathy, then Victoria. Three women murdered in Fell in the past few years. Their bodies dumped like trash. Even if one of them was solved, that still left two whose murderer was still out there. The salesman was the only lead she could think of, the only place to start.

She had a problem: She didn’t know when the salesman would come again. She was stuck for however long, until he chose to check in. If he chose to check in ever again.

When he was here before, he’d left no trace of who he was. Except . . .

Viv thought it over and smiled to herself.

Maybe she wasn’t stuck after all.

Fullepub

Fullepub