Eight

Dunn took his time getting the tea, and Caitlin was glad. She needed a break from those eyes of his.

A lawyer? Lose Swindale?

What rubbish. She'd been granted the deed, fair and square. It had her name on it—that much she could read.

Clearly, Dunn didn't know what he was talking about, and the nonsense about a dower was proof of that. It was not possible that a woman like Caitlin—an Irish wench, a Catholic, a convict from the streets of Cork—could be entitled to a portion of any fancy Englishman's estate. Even if that's what the law said, they'd find a way around it.

But the farm, that was hers .

Even still, she couldn't stop remembering the man at the land office. He'd been quite clear with her when he'd handed her that deed. The only reason she'd inherited Swindale was that John had no will and no known male heirs. If there were an heir . . . and he did try to claim Swindale . . .

She bit down on the inside of her lip and snipped the thought before it could unravel any further. There was no sense in it. Surely this lawyer would clear things up.

Michael passed her a steaming cup. "Would you like me to read the rest?" He gestured to the letters.

"I would."

Wordlessly, he picked up the next letter in the pile, opened it, and began to read.

Happily, there were no more surprises. Mr. Umbrage was looking for payment for the hogs they'd purchased last year. She'd known of that debt, and it didn't worry her. What worried her were the debts she didn't know of. The total of them, from the ledgers.

But that was a concern for another time.

Then there was a note from a merchant ship's captain who was docked in Sydney, asking John to consider a position on his next voyage. The ship had left months ago, and either the captain had learned of John's death or he hadn't. There was nothing for Caitlin to do.

When the letters were all read, she began clearing the tea things.

Dunn remained at the table, staring blankly at the stack of opened letters as she collected the cups and crossed to the basin. He seemed lost and uncomfortable, as if he didn't know what to do next.

She took her time at the sink, trying to ignore the pricking sense of his gaze on her back. It was unnerving. She had nothing else for him to do, and she didn't need the bother of thinking of something.

She wiped her brow with the back of her hand. Gad , she'd be glad when he was gone—

Melia murder. Her hand stilled, then lowered slowly. When had she become so heartless? The poor man was only doing his best. He was quiet, surely, and nervous, but he'd improved since he'd arrived. That wild, dangerous look in his eye, the one that reminded her of a cornered animal, had disappeared. She couldn't quite remember when. Now he seemed only to want to make himself useful. He'd cleaned her kitchen, for heaven's sakes. And he seemed quite content to follow her every order. None of the convicts she'd been assigned over the years had shown quite this type of obedience. Like a true servant. Then again, none of her other assigned men had ever been in service, had they? They'd been pickpockets by trade or thieves or forgers—not professions where one learned any kind of deference. Dunn, on the other hand, had probably grown up with servants. He knew how they should act. And while it was true that Caitlin did not relish the intrusion of a man—any man—into her house, she did quite enjoy being obeyed in this way. Like a fine lady.

And now she needed him, didn't she? To introduce her to this lawyer, to help write the letter to the man in London. Of course, she would still send him back. There was no way she could tolerate a man like Dunn in her house for a full year, but . . . not yet.

And if he was to stay for a time, he should probably meet the other men.

She turned to face him. "I'd like you to come with me and meet the men. Then I'll need to prepare for leaving tomorrow . . ." She thought quickly. Of course, why hadn't she thought of it before? "You can total the debts while I do."

"Very good." He didn't smile, but he seemed to relax at the orders. And suddenly, looking at him, it dawned on her. She'd assumed that by commanding him in this way, she would be demeaning him somehow, that he would resist it, be shamed by it. That's how all her other men had been, and in truth, that's how Caitlin herself would feel in the same circumstance. But Dunn was different, wasn't he? His discomfort came from his own freedom, from having to speak up and think for himself. He enjoyed being ordered about; he really did. It was a relief to him.

She spoke again, testing the theory. "Do you really think it's a good idea? To visit a lawyer?" She deliberately left all the certainty out of her tone, as if she were lost and needed his affirmation.

Dunn's eyes widened, and that uncomfortable, almost panicked look came back over his face. "I—You certainly don't need—"

"Never mind." She shook her head, as if casting the doubt aside. "‘Tis decided anyway." Then she put the command back in her voice. "They'll be thirsty out there. Get the bucket and fill it on the way. We'll bring it to them."

Without hesitation, he rose and crossed the room to fetch the bucket he'd brought in earlier.

Caitlin smiled to herself. She could put up with the discomfort of having him here for a week or two more.

Michael followed the widow out the back door. The midday sun was blinding after the dark of the kitchen, and the heat of it beat down on his bare head and shoulders, sending a trickle of sweat down the back of his neck. He wiped it away. What he wouldn't do for a hat.

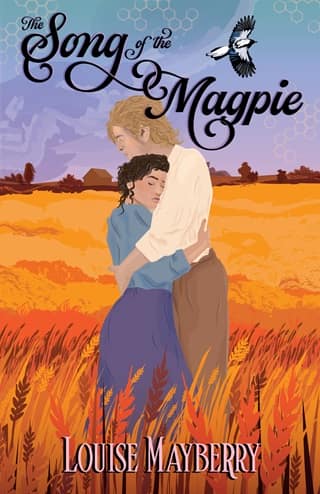

They walked in silence, Michael trailing slightly behind Mrs. Blackwell, past the garden, through a barren field, recently planted—or ready for it—then finally to a wheat field where two men were bent double, swinging scythes. A third followed behind, tying the freshly cut stalks into tall sheaves. The golden waves of ripe wheat rippled in the breeze before them as if they were dancing, while, behind them, the neat sheaves marched away evenly to the end of the stubbled field.

They were a motley trio. One man looked at least ten years younger than Michael, with the dark skin and features of an African. The other two, one fair and one dark-haired, appeared older and more hardened. All were in their shirtsleeves and wide-brimmed straw hats, their faces grimed with sweat. Bits of golden chaff and dust stuck to their skin and clothes.

They stopped when Michael and the widow approached, then peered at Michael curiously between sips from the water dipper he offered.

Mrs. Blackwell ignored Michael as she told Greg, the younger man, of his ticket of leave. His smile grew wide at the news, revealing a thick gap between his front teeth. The other two eyed him, obviously jealous.

"You'll want to go to Sydney and collect your ticket, then," Mrs. Blackwell said. It wasn't so much a question as a statement of fact.

"Yes, ma'am." Greg bounced on his toes, as if he were holding himself back from setting off this very instant.

"If you like," she added, "you could come back here and stay at Swindale while you decide what's next. I've no money to pay you, of course, but you'd have a place and rations. And a portion of the harvest, as I promised."

Some masters made arrangements with their assigned men to receive a share of the profits of their labor. More than once, Michael had petitioned Cowper to do so, as it seemed a small price to pay to keep the men working hard. But Cowper, always shortsightedly focused on his bottom line, had only sniffed and grunted his dissent.

Michael hadn't seen any such entries in Mr. Blackwell's ledgers. It must have been something Mrs. Blackwell had instituted since her husband's death.

Greg scuffed the ground with his foot. "I do appreciate it, ma'am. But I've an idea to go to Sydney. To the docks. I've a friend there, ye see."

Mrs. Blackwell's chin rose. "Of course. I'm to Sydney meself tomorrow. I could take you." Her lips settled into a hard line, but she showed no other outward sign of disappointment. She gazed past the men to the half-cut field, lost in thought. Trying to figure out how she'd do everything with one less man, no doubt. Then, suddenly, she seemed to remember Michael. "This is Dunn." She jerked her head toward him. "He'll stay in the house and work as me secretary." She gestured to the older man with fair hair. "This is Finn." Then to the other, who'd been bundling the wheat. "And Hud." Then, finally to the younger man, "And Greg, of course."

All three sets of eyes fixed on him, looking him up and down. The older two met each other's gazes, and a flash of amusement passed between them.

Mrs. Blackwell stiffened. She had, no doubt, also noticed the men's unspoken judgment. "Back to work then," she told the older two. "Greg, you may take your leave now, if you wish."

Greg shrugged nonchalantly, though he couldn't seem to contain his grin. "No reason to knock off now, ma'am. I won't be goin' till mornin' anyway."

"Thank you." Mrs. Blackwell shot him a smile, and her eyes flicked to Michael. She nodded at him, directing him without words to follow, turned, and began walking toward the house.

Before Michael had taken two steps, the muted voice of one of the convicts sounded behind him in a thick Scottish brogue. "Ye take good care of the mistress now, mate."

Michael wheeled around. It was the one called Hud talking. His face was creased and weathered with a long scar running down one cheek, but his eyes twinkled with mischief. "She deserves a good bit a' action, after that husband o' hers." The man's friend, Finn, grinned knowingly from beside him. Greg, looking slightly embarrassed, took up his scythe and examined the handle.

Michael felt his face go hard. His own idiotic thoughts about her aside, it was clear she wasn't that kind of woman. He took a step toward the man, tightening his expression into the familiar, menacing glower.

Hud lifted his hands in mock apology. "Easy, there, mate. Just lookin' out for her, is all."

Mrs. Blackwell had noticed the exchange and was coming back toward them. Hud didn't move, but the other two jolted into motion, gripping their scythes and turning back to their work.

"What's this about, then?" the widow snapped, looking from Hud to Michael.

Michael didn't take his eyes off the other man as he spoke. "Nothing, Mrs. Blackwell. I was just coming." Meanwhile, Hud shrugged and turned away to take up his place behind the harvesters.

Michael followed Mrs. Blackwell back to the house, not giving in to the temptation to glance over his shoulder to see if the men were watching. They went through the back door, and in the sudden darkness of the kitchen, Michael nearly collided with her when she stopped suddenly and pivoted toward him.

"I'll not have you threatenin' me men." Her chin was raised, and her fists balled. She was angry. Angrier than he'd yet seen her. "They're good workers, and the only two I got left."

Damn. Was that how it had looked? "I—I'm sorry, Mrs. Blackwell." He stumbled over the words. "He insulted your virtue, and—"

"Insulted me . . . what ?" Her eyes widened. "Hud?"

Michael didn't know how to respond. He swallowed.

Her eyes narrowed. "And what did he say, exactly?"

He felt his face flush.

" What did he say? " It was a clear question. He had no choice.

"He implied that I'm here to—to—" Michael stammered.

Understanding dawned on her face. "To bed me," she finished his sentence, her expression staying surprisingly calm.

"Yes." He closed his eyes in shame. "Or—sort of." His cheeks were burning. "He suggested that Mr. Blackwell had not been . . . sufficient in that area. Said you deserved better."

"Well." She sniffed, and an odd kind of grimace came over her face, almost as if she were in pain. Michael expected her to say more, to admonish him further, but she didn't. Instead, her hand came up to cover her mouth, and she quickly turned away.

She stared into the warm ashes for a moment, then turned back to him, that odd look erased from her face. "I've work to attend to. You'll stay here and total up the debts. Then . . ." she seemed to be searching for a command, "then get supper. There's maize for bread and some hard sausage in the larder."

"Yes ma'am."

She started toward the door. "Tomorrow, we're to Sydney. We'll start reading lessons the day after."

"Very good." So they were to start the lessons. She hadn't mentioned it since yesterday, and he was beginning to wonder.

"I'm off, then." Mrs. Blackwell nodded curtly and darted out through the back door.

Caitlin felt as if she might burst.

She walked to the barn, head down. As soon as she was inside, hidden from view of the house, she leaned against the wall and allowed the laughter that had been fighting its way to the surface to finally break loose.

Hud, bless him. He'd been righter than he could ever have dreamed. About John at least.

And that look on Dunn's face as he'd recounted Hud's words, red and stumbling, as if such talk would shock her. As if she were a lady.

He insulted your virtue.

She bent over, her stomach clenched with mirth.

What was happening today? It was one thing after another. The letters. John's lover. His inheritance. Losing Greg. The daft idea she'd lose the farm . . . and now Michael and Hud in a huff at each other over her virtue.

Her virtue.

She'd been a street whore. An officer's mistress . . . her virtue ?

She lost herself to another fit of convulsive laughter. It hurt. She was barely able to breathe. Tears streaming down her face, she braced her hands on her thighs and drew a long, shaky breath, then another, smoothing out the giggles.

She shouldn't be laughing. It was serious, all of it. But what else was one to do?

Truth be told, none of it mattered. Not really. The lawyer would see to any worries about the farm. She'd already known she was losing Greg. It wouldn't be easy, but she'd run the farm with two hands before; she could make do. And John . . . What did it matter that he'd loved a girl so long ago? Or that he'd come into money two months too late? He was gone. It didn't change anything. Not now.

And her virtue . . . well. Virtue would have seen her dead two times over. If she'd clung to such notions, she'd have starved on the streets of Cork, then died of the sickness that swept through the hold of that convict ship during those endless months at sea. It was only as Lieutenant Smyth's mistress that she'd managed to find a place away from the pestilence and hunger the other women suffered.

Perhaps Hud had a point. It had been a long time since she'd known any pleasure in shagging . . . and even then, it had been rare. Whoring was hardly a pleasurable act. Dunn was far from perfect, but he was handsome. And he seemed happy to follow her orders . . .

Gor. She levered herself off the wall and strode toward the threshing floor. Those were the thoughts of a miserable, horn-mad master. One intent on taking advantage. The very thing she'd been on the receiving end of too many times.

Anyway, there were no men in her future. Not Dunn, nor anyone else. She'd had enough of them. And she'd only known him for two days. He could change. He would change. She'd put a wager on it.

Greg had left the flail propped against the weathered wooden wall. She picked it up, testing the weight in her hand. The heavy wood of the beater swung free, ready for its task.

The future— Caitlin's future—would be exactly as she'd dreamed. The fruits of her labor would belong to no one but herself. She'd settle the debts, and in a few years she'd be profitable enough to pay free men in ready money to work her land. Then she'd get a maid, someone to cook and clean while she tended to the animals and the fields. Even if he stayed for a time, Dunn wouldn't be here forever.

She chuckled at the memory of him, cloth in hand, so nervous he'd offended her by cleaning her kitchen.

Her fingers tightened around the wooden handle and she forced the mirth from her mind. She mustn't soften. Not too much. He was a tool, nothing more. Just like the flail in her hands. Something to use, then let go of.

Five years from now, Caitlin would ride into town, just like Esther Abrams, and people would watch as she passed, thinking, There's that woman who surprised us. The lowly Irish who took the luckless cards life had dealt her and turned them into gold.

A buoyant power welled inside of her, and she used it as she lifted the flail and brought it down on the wheat. Thump . The grains shook loose. Again. Thump . Again. Thump .

Michael reported the total of the debts over dinner. Two hundred forty-three pounds. That was the sum of it. More than she'd hoped, but not insurmountable. The wheat harvest would bring in at least half, and she had some money already set aside from the candles and the honey. There would be none left to buy piglets next spring, but with luck she'd be able to get them on credit and sell the excess meat for a profit. Perhaps by the end of next year, she could be free of John's debts.

Then a bitter thought took root. Had John lived just a few more months, he'd have been able to pay off this debt with his inheritance. It wouldn't have made so much as a dent in it.

Although, who knew if he actually would have? He never seemed to think much of the debts, had only paid them when absolutely necessary. A triviality . . . And now she knew why. He'd grown up with wealth. A few hundred pounds probably seemed a pittance.

Before she had a chance to rise from the table, Michael began clearing up, and by the time she'd come back from the barn with the evening's milk, he'd disappeared into his room.

The stillness of the night seemed heavier than usual as she went about her evening rituals. She covered the milk, poured her drop of rum, and stuffed her pipe, then sat on the verandah listening to the chirping insects, letting the drink and the smoke settle her body for sleep. Then she hoisted herself up and went out back to wash and visit the privy.

When she returned, there were noises coming from behind Dunn's door. Was he crying? She turned her head, listening.

Muffled shouts filtered through the thin wooden door. No words that she could make out, but he sounded scared. Terrified.

He must be dreaming. Poor man.

She stood there for what felt like a very long time, not sure what to do. Should she wake him? His cries were so pitiful, so agonized that it seemed the kind thing to do . . . but what if he attacked her? She was certain he wouldn't do such a thing in his waking hours, but if she startled him in his sleep . . .

In the end, the choice was made for her. The noises subsided, replaced by soft snores.

Relieved, Caitlin left the kitchen, padded down the hallway to her own room, and climbed into bed.

Fullepub

Fullepub