Chapter 32

I’ve already been awake for an hour when Magnolia calls me, a hazy distance to her voice like she has me on Bluetooth.

“We’re twenty minutes out,” she says, which makes so little sense I don’t respond for a few long seconds. “Camilla would love for you to join us at this bookstore—if I text you the address can you meet us, or do we need to pick you up?”

I’m under a thin quilt in GG’s office, a tiny back room with a Murphy bed that folds down from the wall. Mick and Silas are in a guest room on the other side of the house, and when I used the bathroom half an hour ago, Cleo was still asleep on the living room couch with her mouth open. My eyes track over the wall opposite the bed: a corkboard cluttered with pictures of grandchildren.

“You’re coming to Switchback Ridge?” I say. “Why?”

“I want to see it.” That’s Camilla, her voice even fainter. She’s probably sitting in the back seat like a debutante. “Silas made it sound idyllic.”

Something churns in my stomach, guilty and sour, at the sound of his name.

“The bookstore’s in a houseboat on the lake,” she continues. “The Bard on the Barge. Mags called yesterday and they’re going to put together a little group for ten o’clock.”

I look down at my lap, where my computer’s open to the notes Ethan emailed me just after midnight. His email is short, but it doesn’t necessarily mean he’s mad. Ethan’s always succinct.

7.12 lecture notes, he’s written. Let me know if/when you want to discuss. E

It’s the if I keep tripping on, the implication of doubt. That he isn’t sure, anymore, where we stand with each other. And the fact that I’m not sure, either. Ethan, the bedrock of my life for the last two years, feels like a murky if/when. Inevitable, but in what way?

“What do I need to do for the group?” I ask, resigning myself to it. Maybe this is a gift, a reason to slip out of GG’s house before anyone else is awake. Avoid whatever it was that happened in the tree house last night.

“Nothing, this time,” my mother says. “Just come as you are.”

Sadie’s awake when I finish getting dressed, and when I tell her where I’m going she asks to come, too. I stare at her across the kitchen, waiting for a flicker of the tension from yesterday, and it never comes. I’m certainly not going to bring it up if it’s blown over, so we just call a rideshare and walk the long, tree-tunneled driveway from GG’s cabin to meet it at the road.

“Sleep okay?” she asks, and she’s probably just being polite but something about it feels pointed. I wonder if Silas told her what happened, if somehow she knows that I absolutely did not sleep okay because I was thinking about the unhinged way he makes me feel, like I’m coming apart at the joints. I lay in the dark staring at the ceiling, sleeping in fits and starts, imagining Ethan across the country—the person who’s always made me make sense. The opposite of how I feel around Silas, like the world is so much bigger than I thought and I’m not sure which part’s mine to own.

I tell Sadie, “Sure.”

“Did you hear the owls this morning?” She’s wearing jeans and a windbreaker, hands in the pockets. It’s cool, still, the morning air clean and new. “Two of them, calling to each other in the woods.”

“No,” I say. “I sleep with earplugs.”

She smiles down at her feet, like she and her sneakers are sharing a private joke. “Efficient,” she says.

“It is.” I glance at her, an apology rising in me. I’m sorry I freaked out at you. I’m sorry I’m so messed up about her. But I can’t make myself draw out the words. When the trees open up to the road, there’s a red car waiting for us, and Sadie motions me in ahead of her. We drive to the lake in silence.

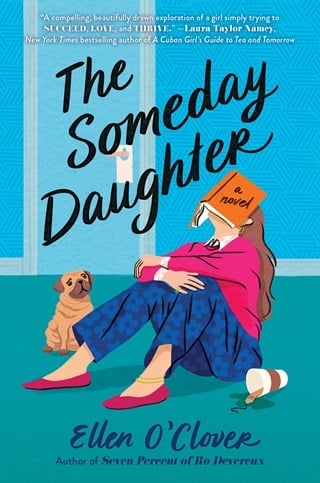

Camilla’s already there when we arrive, three minutes past ten. I’m expecting a few people clutching copies of Letters to My Someday Daughter, but this “little group” turns out to be twenty women sitting on the wood floor with their legs crossed. The Bard on the Barge is a converted houseboat, connected to the lakeshore by a floating dock with rope railings that make me think, against my will, of the tree house ladder.

It’s small and swaying, every wall lined in books behind horizontal dowels to keep them from falling off with the movement of the water. There are porthole windows and a few anchors hanging from the ceiling, like we’re on an ocean liner instead of a landlocked lake small enough to see both sides from anywhere you’re standing.

My mother cuts across the room to us, and I watch a few of the women track her. When their eyes catch on me, they smile.

“Good morning,” Camilla says, dropping a hand on my shoulder and then letting it fall to her side. She looks between Sadie and me. “How was the visit yesterday?”

I glance at Sadie, suddenly terrified that she’s going to bring it up. My used copy of the book, the notes she’s been taking in her own copy, how nasty I was about it.

But she just says, “Great. Audrey charmed the pants off Dr. Sun, as always.”

Camilla smiles. “What’s the best thing you learned?”

I study her, consider her phrasing. The best thing. For me, the best would be the most useful—something tangible I can put into practice. For my mother...

“Dr. Sun delivered the Broncos’ quarterback’s baby.”

Her eyebrows lift, eyes widening a bit. “How fascinating. Was it an easy birth?”

“I... have no idea,” I say. “We didn’t get into it.”

“Was yours?” Sadie asks, and we both turn to her. Her face is neutral, pleasant. But I’m thinking of her eyes in Dr. Sun’s office, how they didn’t move from that photo on the wall—a new mother in a hospital bed, her baby sleeping beside her.

Camilla hesitates. “With Audrey?” I think, Who else?

Sadie’s eyes flick to mine, and she hesitates herself before saying, “Yes, with Audrey.”

“Not particularly,” my mother laughs, pressing a hand to her stomach. I know I was weeks early, that she lost enough blood to stay in the hospital for a few days. That my dad was the one to hold me in all those first hours, to give me somewhere warm and close to meet the world.

“Oh.” Camilla looks across the room, where Magnolia is giving her a signal. “Looks like it’s time to get started.” She flashes a little smile before turning from us, picking her way between all those women sitting on the floor.

She lowers herself onto some kind of bejeweled pillow at the front of the group, crossing her legs.

“I always find it hard to get into a state of mindful presence mentally,” she begins, “without first getting there physically. If you’ll all indulge me, let’s close our eyes together and breathe into our bodies.” Everyone closes their eyes when she does, but I keep mine open. Sadie’s next to me, the two of us leaned against a community board full of flyers for dog walking and music lessons and summer tutoring. I glance at her, and her eyes are open, too.

“Identify a feeling,” Camilla tells the group. “Any single one, whatever’s bubbling up for you. None of them right or wrong. That’s the thing about feelings—they don’t come with value judgments, they just are. A feeling cannot be wrong, it can only be. Honor the feeling you’re identifying right this moment.”

And—okay. It’s froofy, right? This is therapy soup. This is the hot, intangible, emotional roil that pushed me into the sciences. That has me reaching two-handed for the factual at literally all times. But standing here, the room full of books and quiet and only Camilla’s soft voice, I kind of believe it for a second.

Or maybe it’s that I want to believe it. Because all the feelings I’ve been having lately—the panic that pushed me into Lake Michigan after Puddles, the hurt of Ethan acting like he doesn’t understand me anymore, whatever it is that consumes me any time Silas is around—I hate them. I’ve been absolutely roasting alive in how much I hate the feelings tornado my brain has turned into this summer. I’ve been desperate for the Audrey I knew even a month ago, so sure of all of it—how I feel, who I am, where I’m going.

But here’s my mother, saying any feeling is okay. Telling me to honor that mess. And god, isn’t that tempting? Wouldn’t it be so good to move through the world that way, without policing yourself? Standing there on that swaying book boat I feel it for the very first time: a modicum of understanding. Why all these women love her so much.

“Now,” Camilla says, “let’s breathe one layer deeper. Fill your lungs, and as you inhale try to identify the voice of that feeling. What is she saying to you?” She pauses. Giving everyone time to find the voice, apparently. “If it’s kind, thank her. Thank that voice for bringing you here today, to this space we’re creating together. If it’s unkind, offer her sympathy.” She inhales. “She didn’t choose unkindness; something taught it to her.”

When Sadie looks over at me, I realize my eyes are stinging. I duck my chin, blinking the tears back into my brain. What the hell is happening right now? As my mother keeps talking, I turn to face the community board so I don’t have to look at her, or at Sadie, or at anything else.

“Ask the voice how she might change if she were speaking to someone she loves,” Camilla says.

My gaze is burning a hole in the community board, laser-beaming a tutoring flyer. It’s some hand-drawn, mass-copied thing, shouting Coding Tutoring!! with two fat exclamation points.

“If, for example, that unkind voice was giving the same message to a young girl—to your own daughter—would she rephrase it? Would she deliver it with more grace, more love?”

Middle/high school students, the flyer says. Caltech student home for the summer. [email protected] for details. I mouth the words to myself, try not to hear what Camilla’s saying.

“And if she would, tell the voice: I am deserving of all that same grace and love.”

Sadie shakes her head, movement in my peripheral vision. When I look at her, she leans into me and whispers, “She’s kind of amazing, huh?”

I swallow, flick my eyes over to my mother. Hers are open now, surveying her little group. She’s holding one woman’s wrist, and as I watch she squeezes it and then reaches for another woman, taking the hand she has upturned on one knee. The woman’s eyes open, and Camilla smiles at her.

So much of my mother’s life is performative that I’ve forgotten, maybe, she’s an actual human being. She’s a living fifty-four-year-old person. She’s here in this room, where there are no cameras and no lists of talking points, holding some stranger’s hand to make her feel like her inner self is deserving of grace or love or whatever it is.

It hits me in the roof of my mouth, thick and choking. What this reminds me of. It’s GG’s dinner table last night—sauce-stained plates pushed to the side, Apples to Apples cards strewn over the uneven wood, Mick howling with laughter, evening air breathing through the open windows. This feels like that. Warm. A moment carefully gathered to make everyone in it feel like they belong there.

I think of Sadie in Santa Fe: It was you pushing her away. Of Dad in Austin: We’re your parents. We love you. And of myself, so angry at Camilla for so long, so desperate for her to see me as I actually am.

And so unsure, suddenly, if I’ve ever done the same for her.

Fullepub

Fullepub