Chapter 11

The media called it the Sex Summit. They wasted no time giving it a cute nickname, a moniker so charming it felt ghoulish. There was nothing cute about that weekend, about the way everything went down—but the photos leaked to the press (by who? My money’s on Magnolia) were irresistible.

Picture it: a standard-issue dormitory hallway, its concrete-brick walls, its scuffed laminate floors. Each side lined in sixteen-year-old girls, most of them wearing pajamas. Hair in topknots, makeup headbands slipped over foreheads, fuzzy slippers jutting into the aisle. And at the end of the hall, just outside the door to my room: Camilla St. Vrain, celebrity psychotherapist turned wellness empress, holding an oversized poster diagramming female sexual anatomy.

The Summit School wasn’t religious anymore, but it had been. There were still a few tortoises on the school board, bow-tied old men who kept sex ed out of our classrooms. My mother was fresh off a talk show appearance that she’d ended by admitting to wearing a rose quartz yoni egg for the entirety of the interview—rose quartz, she informed everyone, because it opens the heart chakra to self-love. Saint had started selling “love and intimacy” products six months before. The yoni egg stunt cemented her status as a guru of sexual pleasure and well-being.

So I shouldn’t have been surprised, I guess, that when she showed up on my dorm hall in the spring of my sophomore year, people had questions. Enough of the girls on my hall cornered her to ask for advice that she took matters into her own perfectly manicured hands. I stumbled out of bed, bleary-eyed from a starved and sleepless week, to find her posted up like that with the diagram. Talking about the clitoris like it was a word we normally threw around with casual abandon.

The school was furious. There were letters sent to parents, meetings with the headmaster, assumptions that I’d asked for this. At one point I thought I’d be expelled, but when the media caught wind of the story, the Summit School came under so much fire for their arcane lack of sexual education—in a liberal city in a blue state, no less—that they had no choice but to let me stay.

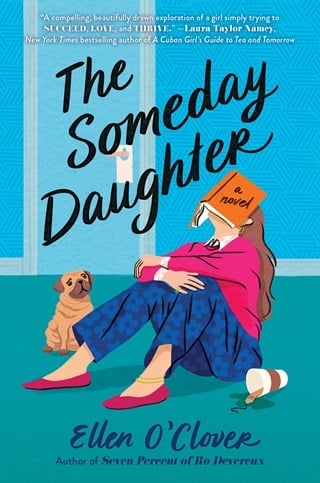

Camilla emerged looking like a hero. Letters to My Someday Daughter hit the bestseller list again for the first time in years. The narrative was clear: Camilla St. Vrain, liberated feminist icon, swooped in to save her daughter and all her daughter’s friends from conservative sexual repression. Camilla St. Vrain thought that, if you were going to be having sex at sixteen, you should definitely be having orgasms. Not only that, she’d tell you how to make it happen.

Could Audrey St. Vrain possibly have a cooler mom?

No one thought to ask the only question actually worth asking, which was why had Camilla St. Vrain showed up at the Summit School in the first place, smack-dab in the middle of the semester?

It wasn’t because I wanted a sexual education from her, I’ll tell you that much. The answer was simpler and worse: I’d become a problem nobody knew how to solve.

By the time I was sixteen I’d lived at the Summit School for five years—it was more of a home to me than anyplace had ever been. While my role in Camilla’s life had always felt complex, my role at school was simple: I was the smartest. I didn’t score below a 98 on an assignment from the moment I set foot on Colorado soil. That school was my home and my family and my identity; somewhere I could rise. Then I got to second-semester chemistry, and everything changed.

The coursework was simple: the periodic table, conversions, atomic electron configurations. Then spring rolled around and suddenly we had labs. Hands-on. Science in practice instead of in theory. In the quiet of my dorm and the familiar rooms of my own mind, it all made perfect sense. I could walk through each part of the lab in advance, knowing exactly how to perform its reactions. And then I’d set foot in Mrs. Barclay’s classroom, lean over the black lab counter, and become someone else entirely. My fear of getting it wrong ate me alive from the inside, hollowing me until my observations were off, until my reactions unfolded incorrectly, until my pipetting hand was dangerously unsteady. I felt sweaty and conspicuous, like each time I made a mistake I grew three inches until I took up the entire room, until all anyone could see was the enormity of my failure.

It was the first time I’d needed to apply knowledge in the physical world, and the pressure of not messing it up ensured that I did, every single time. How the hell was I going to be a doctor, I berated myself, if I couldn’t excel at a tenth-grade chemistry lab?

My lab grade that semester was like a downward staircase: every assignment took me further into the dark and shameful basement of myself. The only saving grace was that 70 percent of our chemistry grade came from written work and exams. Only 30 percent of me was drowning. But then Mrs. Barclay assigned lab demonstrations for our midterms—my absolute nightmare. I’d have to stand in front of my entire class and fail in real time. No one would be focused on their own reactions; they’d all be focused on mine, and I’d have to admit what a fraud I’d turned out to be.

The panic came on slowly—nagging headaches and aching joints—and then, in the days leading up to the midterm, all at once. Two days before I was scheduled for my lab demo, I stopped getting out of bed. It wasn’t a choice; it was a paralysis. A curtain falling, a twisted root growing from the base of my brain stem and binding me to my bed frame. It’s not even that I was sleeping—I couldn’t rest, couldn’t think, couldn’t eat. I could only sit still and try to swallow the endless wail that had taken over every part of me. My body was a wince; I was made of fear and failure.

I missed the midterm, obviously. I missed three days of classes before Fallon finally called my mother. I remember barely anything from that week, but I do remember the way her voice sounded, like she knew she was betraying me. I’m so sorry, Audrey, when I looked at her as Camilla walked unannounced into our room. I didn’t know what else to do.

My mother got me to the counseling center, where a bespectacled therapist asked in a humiliatingly sympathetic voice if I’d ever talked to anyone about my anxiety before. But I wasn’t anxious; I was possessed. Something had stolen into me, but after days of being paralyzed by it I’d developed the necessary antibodies. Now it was gone. I explained this to her.

“Audrey,” she said, and I remember thinking how strange it was for her to use my name, for us to know one another at all. “Why do you think you chose that word? ‘Possessed’?”

I blinked at her. Why did anyone choose any word? Words were just words, empty vessels. In my silence, she kept on—eyes gentle but unwavering on mine.

“I wonder if it’s to create distance,” she said. “To separate yourself from this feeling—to other it, instead of accepting it as a part of yourself.”

I stood, then. Because she didn’t understand; she wasn’t listening to me. This entire experience had been other. It wasn’t part of me; it was something happening to me that I would never allow to happen again. As I walked toward the door she recommended that I come back to see her and I did not.

Camilla coordinated with the school and Mrs. Barclay so that I could make up my midterm with a written assignment. She didn’t address how she’d found me, or what I’d done. When I finally fell asleep after a week of eye-clawing insomnia, she posted up in the common room at the end of my dorm hallway and taught every girl I lived with about consent and pleasure.

And that became the story of her visit. That became the Sex Summit. That became a cornerstone in the public lore of our relationship; the infamous Colorado weekend Camilla spent with her someday daughter. She leaned right into all of it, playing it up as the wackiest time of our lives, when in reality I’d never been so scared.

In the span of just a few days, the world had come to know me as someone in tune with herself, someone who could talk openly about sex, someone absolutely comfortable being emotional with her mother. The few discerning people who asked why I wasn’t actually in any of the photos from that weekend were brushed off like water from a duck’s back. Audrey doesn’t like to be photographed, Camilla said, instead of telling the truth. And I, of course, respect her right to privacy. In reality I had been trapped, alone, inside myself. But we both played into what the world thought me to be after that.

It was clear that what I’d done was something to be covered up. A shame too terrible to name. Camilla thought that there was something wrong with me, and we would hide it. I knew then that as long as I was the best—as long as I was smart and successful and well-adjusted—there would never be a moment like this again.

I doubled down on school, on college research, on all of it. I signed up for the Summit School’s student EMT program the minute I turned eighteen. I bandaged cooking burns and stabilized broken ankles and wrung every fear of performing out of my body. I proved to myself that I was, after all, the person I knew myself to be.

Camilla and I never spoke of that weekend again.

Fullepub

Fullepub