Daisy: March 2020

I wake with a start, my mouth dry and sticky with the remnants of a troubled sleep, and reach for the bottle of water next to my bed. Violet’s letter lies beside it and I refold it and return it carefully to the plastic bag containing the rest of her letters and notebooks.

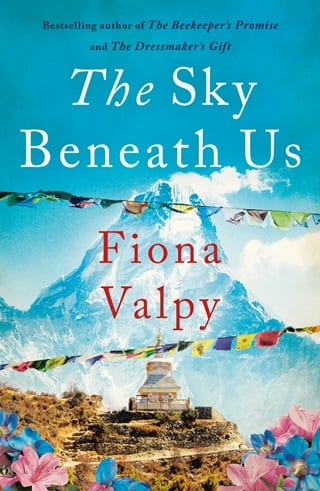

Outside my hotel window, an altercation breaks out in the street with a blaring of car horns and a storm of shouting. I open the curtains and squint in the glare of bright sunlight. Despite my body clock telling me it still feels like the middle of the night, it’s already late morning and Kathmandu is a hubbub of noise and commotion. I check my watch. Having tossed and turned for much of the night, I’ve now overslept and missed the hotel breakfast. Everything is different here, even time. It’s not just the hours and minutes that are strangely offset from the rest of the world. Nepal is a country with six seasons, not the four I’ve been so used to, and has its own calendar, the Nepali patro , in which the number of days in the months vary annually. And simply by landing here, I’ve been catapulted forward almost fifty-seven years. Things I’d always assumed were certain and dependable have been turned upside down, calculated instead by reference to holy festivals, the location of a sacred mountaintop and the arrival and departure of monsoon rains. I suppose, now I think about it, these things are just about as arbitrary as lines of latitude and the phases of the moon, and probably a good deal more relevant to the people who live here.

I climb into the shower and let the blast of tepid water wash away some of the bleariness of my jetlag and the muddle of my thoughts, trying to bring myself back down to earth.

Once I’m dressed, I check my phone, hoping for a message from one or other of my twin daughters, Sorcha and Mara. Instead, there’s a reassuring text from Elspeth: Lexie’s doing okay. Don’t worry, and don’t change your plans. I’ll keep everything running here.

She’s my mum’s best friend and has been since childhood. She’s always helped run the music school and has been like a surrogate mother to me.

And there’s another message, a light-hearted one from Elspeth’s son, Jack. I guess she’s told him what’s happened. I’ve known Jack just about my whole life and he’s as much of a brother to me as Stu is. When we were kids, Jack was always the ringleader on our expeditions. He thought he could boss me around, being almost two years older, and some of the time I let him because he often came up with the best ideas for building rafts out of flotsam and jetsam or going down to the pier at Aultbea to catch crabs on our handlines.

After I left school our paths parted, although somehow we’ve always kept in touch, through all of life’s ups and downs. And there have certainly been a few downs, over the years, for both of us. Though my own preoccupations pale into insignificance against what Jack and Elspeth went through.

His dad ran a fishing boat out of Gairloch and the sea seemed to run in Jack’s veins. He was on his dad’s boat the day of the accident. I don’t think he’s ever stopped blaming himself, even though it wasn’t his fault his father’s foot got caught in the bight rope while they were shooting creels, dragging him overboard and pulling him under. And although Jack was quick to cut the engine, by the time he managed to pull his dad from the water, it was too late. Jack couldn’t bring himself to work the creels after that, even though Davy tried to help him.

It was about that time that I began to see Jack in a new light. Instead of a sometimes annoying older brother figure, I suddenly saw him in his own right, as the devastated young man he’d become. He was so changed by his dad’s accident, and the grief that engulfed him and his mum.

He got roaring drunk at my wedding, and soon afterwards he left Aultbea for good. I think it broke Elspeth’s heart to see him go, but she said she couldn’t bear seeing him so sad and so lost and she’d rather he went away to find his happiness if it wasn’t to be found at home.

Jack took off to explore the oceans and picked up work along the way skippering fancy yachts in the Caribbean for millionaires. He still sends me texts and WhatsApp messages from time to time – photos of white sand beaches to make me jealous and jokes to make me smile.

This latest message, sent to cheer me up a bit I guess, looks as if it’s been taken in some exotic port. It’s a photo of a man with a quiff of suspiciously black hair and long sideburns, wearing a satin shirt undone almost to the navel. ELVIS LIVES is the caption. Followed by I intend communicating only in anagrams from now on. SAFE TRAVELS = FARTS, LEAVES. I text back a laughing face emoji, then set my phone aside and pick up the itinerary that Mum and I spent so many hours putting together, researching places to visit during our first three days in Nepal.

We’d planned to spend the time acclimatising in Kathmandu before catching the plane to Lukla to meet our guide and begin our trek into the mountains. Sightseeing on my own isn’t nearly such a tempting prospect though. I decide to head straight for the Garden of Dreams, where I hope to soothe my frayed nerves and find something to eat. When we read the name, Mum and I both immediately agreed we had to go and see it, even before we’d found out anything more about this magical-sounding place in the middle of the city. I put the first of Violet’s journals into my backpack to take with me. If I have to do this alone then at least I can take the spirit of my great-great-aunt along with me for moral support.

The garden isn’t far from my hotel, but it takes me more than half an hour to get there. There are several roads to cross and the ceaseless stream of tooting mopeds and taxis terrifies me. I watch for a while to see how the locals navigate their way across and realise it’s a case of taking your life in your hands, stepping out in front of the oncoming traffic with your heart in your mouth, praying that they’ll either stop or swerve just enough to avoid you. I wait for a small group to gather on the kerb before taking my lead from them. Miraculously, no one is run over and the veering, hooting scooters manage to avoid one another by a hair’s breadth.

I trot along the uneven pavements, picking my way between the potholes and rubble. More than once, as I struggle to read the map, I trip over paving stones and tree roots, staggering, almost losing my footing. I’m attempting to look confident and purposeful, as the guidebook tells me I should, in order to avoid attracting the unwanted attention of hawkers and hustlers, but I know I am easy prey. I carry on walking, doing my best to shake off the small procession of street vendors that trails in my wake. I’m thoroughly relieved when I turn in at the gate that marks the entrance to the garden. Barked at by the guard, the retinue melts away in search of other prey, and I pay for my ticket at the kiosk.

Immediately, it’s like stepping into a parallel universe. The Garden of Dreams is an oasis of calm, the clamour and bustle of the city streets muffled beyond its high stone walls. I sink gratefully on to a bench, giving myself a few moments to allow the pounding of my heart to subside, regathering my tattered nerves.

The first thing I then notice is the birdsong. I suppose it’s everywhere in the city, but it’s only when the din of the traffic fades that it can be heard. The bass cooing of pigeons is overlain with the treble notes of other birds, high and pure as a flute or soft as an oboe’s liquid tones. It reminds me of walking along the hallway at Ardtuath House, hearing the sounds of instruments being practised behind closed doors. I sit for a while, closing my eyes to absorb the sounds.

When I open my eyes again, I become aware of the play of sunlight over my face and a sweet scent drifting on the air, enticing me deeper into the gardens. I gather up my bag containing Violet’s papers and begin to walk. The space is filled with colour and perfume from the plants that grow here – cascades of jasmine, a tapestry of roses, the teardrop flowers of angel’s trumpets, and a clump of headily fragranced white orchids hiding in the shade of a fig tree. As I wander along the paths, I imagine I feel the presence of Violet beside me. The exotic birds and trees remind me of the descriptions I’ve read in her journals and the flowers seem familiar to me from the botanic watercolours she painted, crowding the walls of the library in the big house. I pull out my phone and snap some photos to send home to Mum, my spirits lifting a little as I do so.

The focal point of the garden is a pavilion, its domed cupola supported by elegant cream columns. According to the leaflet I was given with my ticket, this is where the café ought to be. But I find the doors locked and a hand-scrawled notice saying it’s closed until further notice due to the virus. I spot a white marble plaque set into the wall and step closer to read the writing on it. It bears four stanzas translated from the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam , but they’re made difficult to read by a cobweb of cracks radiating from the third of the verses. I peer at it more closely.

Ah, love! Could thou and I with fate conspire

To grasp this sorry scheme of things entire.

Would not we shatter it to bits – and then

Re-mould it nearer to the heart’s desire!

And then I read the engraving on a smaller metal plate set beneath it:

The crack in the marble plaque, now disguised as a creeping vine, is said to have been the only damage to the garden caused by the Great Earthquake of 1934.

Instead of replacing the broken slab of marble, someone has instead turned the damage into a part of the design by etching leaves and flowers along the cracks. I sit on a bench beneath it, turning every now and then to reread the words and absorb their broken beauty. It’s as if Violet has reached out to me and taken my hand to guide me here. If I needed a sign of encouragement to continue on this journey, then surely here it is. The message is loud and clear ... life falls apart; and maybe some things can’t be mended, but perhaps they can be reshaped into something even more beautiful. In the sighing of the breeze and the calling of the birds, I imagine I hear her voice too. Keep going , she says. Keep putting one foot in front of the other, just as I did. You’ve taken the first steps – now see where the path takes you.

I pull her journal from my bag and settle down in the jasmine-scented shade to read.

Fullepub

Fullepub