Prologue

Oxford

The scent of the rain summons the memory. Uninvited. Unwanted.

She is in the garden. It is late December, seven months after Will's death. She is digging into the frozen ground. There is no order to the way she tackles the work. All she knows is that she wants to gouge her pain away.

Rain falls as she scrabbles in the earth. She has become used to waves of disorientating anger, but this is new. She thinks her rage will consume her.

When she spots some early snowdrops peeping through a pile of old leaves, she pulls at them, ripping them from the soil. The sight of the pure, hopeful flowers is more than she can bear.

As the earth runs to mud and soaks into her frozen skin, she rocks back and forward on her knees, the tiny flowers crushed in her hand.

Five months on, the rain on the partly open window is different– a May flurry making a blustery fuss before passing on. But something in the metallic fragrance lingers, conjuring the past. Emma looks at the blank laptop screen in front of her and wonders why she is finding this so difficult. It should be a simple enough thing to write: I resign. I quit. I shall be leaving. They are just words. It shouldn't be this hard.

There have been times when she has found exactly the right words. Experienced the satisfaction of hearing a phrase settle just where it should, like a child posting the right shaped brick into the exact shaped slot. In the main, she associates these moments of succinct expression with the clinical environment of the lab in which she works, where everything is measured and nothing is left to chance.

But outside of work, in a world untrammelled by lines of white tiles, she finds her words are more likely to twist out of shape, like a scarf caught in the wind, swirling mid-air to wrap themselves with unintended meaning around the recipient. Either that, or her words are lost, carried away to be trodden, unnoticed, underfoot. Fear of saying the wrong thing makes her falter, and in that hesitation, she feels the substance draining from her words until all that is left in her mouth is a whisper. Then the best she can hope for is a pause, and a ‘Sorry, Emma, did you say something?'

Still, better that. Better to watch, helpless, as the phrases flap quietly away, than to be a person who holds words securely between a thumb and forefinger, ready to press them with precision into the softness of flesh, burying them with a persistent, thrusting thumb so that they will eventually take root. Not to grow outwards to the sun but to burrow deep into the heart of you.

Emma wonders why she has started thinking about her mother– a woman who can plant words in her flesh like a seasoned gardener.

Ten minutes later, Emma looks down at her brief words of resignation. She knows the time has come. She has just turned forty, and she wants a change. There will be more research to do on the degenerative condition they are studying, working with other universities around the world, but they will have to tackle it without her. She suspects her colleagues will miss her grasp of languages– she is fluent in Spanish, Italian and French– but will they miss her ? She doubts it. And, apart from the languages, there are others who can take her place. The team's PhD student is clearly itching to step into her shoes, and there is no doubt that he could. Literally. Emma is exceptionally tall and has always had large feet. She long ago gave up wondering why such a shy person was given a body and hair (corkscrew curly and very red) that make her so glaringly obvious in any crowd. Neither her science nor her grandmother's God has ever provided a satisfactory answer to that one.

She wonders who she will tell about her decision. Her stomach and heart take the plunge down the well-worn track of those she wants to tell but can't– her husband and her dad– and there is still, after all this time, the residual surprise that, once, once , she was happily married. She did find someone. And not just anyone.

This never fails to amaze her.

Suddenly, there is something she needs to find. She unearths it from under the bundle of clean washing that is piled at the end of the table– the local free paper. The pages are turned over to the small ads. What she is looking for is ringed in black.

She frowns as she reads. Her memories of her father are invariably linked to his garden. Is this why it had jumped out at her? Could this be the change she is looking for?

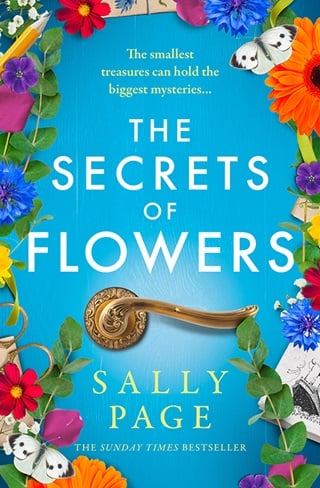

Wanted: Florist to work part-time in garden centre.

Experience useful but not essential. Training can be given.

Own car helpful.

Must be friendly and good with people.

Emma re-reads the advert.

Well, at least she has her own car.

Fullepub

Fullepub