Chapter 2

Chapter Two

M alcolm Douglas Thornton, the Laird Mac Sceacháin, or Col to a few intimates, stuck a fork in the piece of mutton on his plate and wrestled his knife through the tough sinews. The fire behind him crackled in the hearth and the clock ticked on the mantelpiece, the only sounds other than those of his dinner companions’ knives wrestling with the meat. He sat at the head of the table as befitted the head of the house, and his sons—dark-haired Rory, twelve, and ginger Callum, ten—flanked him. Beyond them sat his elderly servant Fergus and Fergus’s grandson Willy, a freckled ginger like Callum, but darker. Such was the extent of his household.

The blessed silence suited his mood; the melancholy had been bad since his brother Merlow had left with his new wife, Hetty, after a fleeting visit of but a fortnight. Hetty’s presence, as wonderful as it had been, had stirred up all kinds of memories, and Col found himself plunged once more into the kind of dark fog he had not experienced for a year or more. The black melancholy had plagued him on and off in the six years since his wife’s death, but less and less in the last two years. Now it was threatening to come back and swallow him whole once more.

To have a pretty woman in the kitchen cooking delicious meals, cleaning the layers of dust off the furniture, putting flowers in vases, and singing—singing! Col shook his head to shake off the memory. It hurt too much.

And to see his brother happy—not that he begrudged him his happiness. Merlow had waited a long time to take a wife, and he had chosen well. The lass was perfect for him: a vicar’s daughter, full of good works and hardworking spirit, and the love between the newly-weds was palpable. And her presence had cut up all Col’s hard-won peace.

He had thought himself accustomed to his widowerhood, resigned to this lonely state before she came. After she left, he realised all over again what he had lost with Catriona’s death.

“Ow!” exclaimed Callum, jerking in his seat and glaring across the table at his grinning elder brother. “What was that for?”

“I was aiming for the dog and your knee must have got in the way,” said Rory, chewing on his bone.

“Ye’ll nae kick the dogs!” roared Col, slamming his fist on the table and making everything jump.

Rory turned a sullen face towards him. “It was a joke, Papa, of course I wouldn’t kick the dogs.”

“But it’s alright to kick me!” muttered Callum.

“Nae, ’tis not alright to kick ye,” replied Col. “Ye’ll apologise to yer brother,” he addressed Rory.

Rory pursed his lips and remained silent.

“I said,” repeated Col, dangerously slow, “ye’ll apologise to yer brother.”

Rory rose and threw his napkin on the table, turning to walk away.

Col shot out a hand and grabbed his arm, yanking him back around. “Ye’ll do as I say, boy, or get yer breeches clouted!”

Rory stood silently seething, his fists clenched by his sides. “It was an accident. I swung my legs too far out, ’tis all! I didnae mean to kick him!”

“Tell it to him, not me!”

Rory turned his head and addressed his brother sulkily. “I’m sorry, ye little winger! I didnae mean to hurt ye! Ye’re such a puling little thing, always crying aboot somethin’!”

“Now sit down and finish yer meal!” Col yanked him back into his seat. Rory resumed eating and Col glowered at both boys over his pot of ale. Callum sniffed into his plate.

Col knew from experience this wouldn’t be the end of it. Callum wouldn’t be able to resist retaliating in some way.

The sequel came quicker than he expected. He’d withdrawn to his study with his dogs, Hector the terrier and Gussie the deerhound, for a glass of whisky, when a blood-curdling howl brought him out into the hallway.

“I’ll kill ye, yer little gobshite!” bellowed Rory, appearing at the top of the stairs, something clutched in his hands. “Ye’ve ruined me buckler! Ye fooking little worm!” He dropped the buckler and took off after a cackling Callum down the hall. A shout and slammed door told Col that Callum had made it to sanctuary and locked the door in his brother’s face. As Rory pounded on the door and shouted insults through it, Col climbed the stairs to deal with this latest chapter in the war between his sons. It had erupted following Hetty and Merlow’s departure and had been raging now for two weeks with no signs of abating. It seemed he wasn’t the only one impacted by Hetty’s absence.

Reaching the top of the stairs, he strode down the corridor and seized his eldest son by the collar and shook him. “Enough! I’ll deal with this, go to yer room and stay there!”

“But he—” began Rory, red-faced and puffing.

“I said I’d deal with it. Now get!”

Rory threw him a venomous look and turned away, muttering.

“What was that?”

Rory stopped, his shoulders hunching. “Nothing, sir.”

Col yanked him round. “Say yer piece!”

Rory’s fists clenched and he let fly, “Ye always favour him, and he’s such a weakling! It’s nae fair! Grandpa would’ve flogged him for half the things he’s done!”

“If ye didnae bait him in the first place he wouldnae retaliate! Ye bring it on yerself, boy! Ye’re bigger and stronger than him and ye know it. But he’s the one with wits, use your heid a bit more, boy, and ye won’t find yerself in so many scraps!”

“Grandpa—”

“Yer Grandfather’s dead, lad, and ye’re stuck with me! Not yer preference, I know, but I’m Laird now and ye’ll do as I say. Now go to bed before I clout ye round the heid for disobedience!”

Rory brought his fists up. “Go on then!”

Col looked down at him and suppressed the urge to laugh, a faint wisp of pride surging through his chest. Rory was a brave lad. Foolish, but brave. If he didn’t infuriate me so much . . .

Col scooped the lad up under his arm and marched him down the hall while Rory yelled at him and rained wild punches with his fists against his stomach and chest. He opened the boy’s bedroom door, dropped his eldest son onto his bed, and shut the door, turning the lock. “Stay there ‘till yer heid’s cool!”

A bellow of outrage and a few thumps of things being thrown at the door followed him down the hall to his other son’s room. On the way, he stopped to pick up the dropped buckler and examine the damage.

A deep gouge across the Sceacháin escutcheon, featuring a bear rampant, which was carved into the buckler, bore mute witness to Callum’s spite. The buckler was a family heirloom dating to at least the 16th Century and probably earlier. His father had gifted it to Rory as the eldest son and heir. The old man had made no secret of his favouritism towards Rory over Callum, an echo of his preference for Col over his brother Merlow as they grew up. That preference had driven Merlow from his home and caused him to be absent when their father died.

A sudden fury with his father seized Col at this evidence of the damage his favouritism wrought even beyond the grave. He himself was hard on Rory as his father had been on him, but tried where he could, to temper his natural toughness with his younger son, having seen what happens when a father rejects a more sensitive boy. Merlow had simply left home and never come back until after his father was gone.

But staring at the spiteful damage to a family heirloom made it difficult to be sympathetic towards Callum in this instance. Tightly reigning in his anger, he stopped outside Callum’s door.

“Callum!”

Silence.

“Callum, open the bluidy door or ye’ll regret it!”

After a moment he heard the lock being turned, but the door still didn’t open. He pushed the door open himself and stepped into the room. Unlike Rory’s room, which was a mess, Callum’s was neat as a pin.

Callum sat on his bed staring at the floor.

Col shut the door behind him and leaned against it, the buckler clutched in one hand, his arms crossed. His heart thudded heavily in his chest, and he felt slightly sick. After a moment or two of silence he prompted, “Well, what have ye got to say fer yerself?”

Callum shrugged and kept his head down.

“I should belt the living daylights out of ye for this, Callum. This is a bluidy heirloom! Have ye nae respect for the family name?”

Callum shrugged again and something in Col snapped. Dropping the buckler, he strode across the room and hauled the boy up by his collar and shook him.

“If ye’ve none, I’ll teach it to ye!” he growled. “How dare ye take yer petty spite out on something that matters so much, not just to yer brother but the whole family! Generations past and future. There is nae balance in yer revenge, boy! Rory’s crime doesnae match your vengeance, nae even close!”

Callum hung his head but said nothing beyond a faint whimper.

“Drop yer breeches, boy! Ye’ll nae sit down for a week! And think yerself lucky to escape with nae more than a belting.”

He removed his belt as Callum let his breeches fall and bent over the bed.

Col left his son weeping into his pillow, his bottom red raw from the strapping. He unlocked Rory’s door, but there was no sound from within, and he left the boy alone, taking the buckler with him. Downstairs, he sat it on the table beside his chair and resumed his glass of whisky, staring at the marred design until his eyes blurred. Gussie lay at his feet and Hector leaped into his lap and settled.

He finished the glass and poured another from the decanter.

The morning light found him still in the chair, the fire burned down and the decanter empty. His head was pounding and his bladder full.

With a groan he moved, dislodging Hector, who leaped down to the rug and stretched with a squeaking yawn. Gussie sat up and thumped her tail, floppy ears flapping.

He blinked blearily at them and muttered, “Fook, me heid’s like to split.”

Rising, he staggered towards the door and out into the hall towards the kitchen and the rear entrance to the house. Emerging into the glare of the early morning, he squinted and headed for the pump, where he dunked his head in the trough and drank some fresh water from his cupped hands. Straightening, he stretched his creaking back and filled a bowl with water for Hector; Gussie was tall enough to drink from the trough.

Hector drank and then cocked his leg against the trough.

“Good idea, mate,” murmured Col. He moved over to a bush, opened his breeches, and relieved his bladder.

It was a fine morning, slightly misty and judging from the position of the sun, still quite early. The dogs frisked about, and he said, “Alright, we’ll go fer a walk, shall we? Blow the cobwebs out.”

He left the courtyard behind the house, setting off across the lawn towards the trees. The dogs gambolled about chasing smells, and he lengthened his stride, wanting to get the blood flowing, his thoughts on last night. He needed to do something about the boys, but he was at a loss to know what. He was reaping the consequences of his own neglect of them following Catriona’s death. He’d been so grief-stricken with the loss of her and their third child, a girl, he’d lost sight of what was important.

He’d dragged himself out of that pit of despond eventually, but by then the damage was done. What frightened him now was the fear that he was about to slip back into that place again. It had been over six years since Cat was taken from him. He was resigned to being alone for the rest of his life, but it was unfair to his boys to let his misery dictate their lives as well. Callum’s actions last night had shocked him to the core.

The dogs had wandered off, and he was so sunk in gloom he didn’t register anything until the blow between the shoulder blades sent him stumbling forward onto his knees.

A cry of “Aiyee!” behind him was all the warning he got before he was knocked flat on his face by another blow and something heavy landing on his back. If he’d been less hungover and more awake, his reactions would have been quicker. As it was, he lay stunned with the breath knocked out of him for a moment before he heaved sideways, throwing off the person who had landed on him, and discovered his assailant was female.

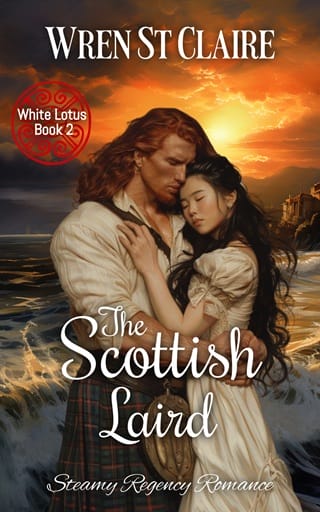

At least he thought she was female, but she was the strangest one he’d ever seen. She had long straight black hair in a ponytail and a delicately featured face with long, narrow black eyes, and she was dressed in a blue silk tunic and wide-legged pants. She had a pack on her back, and she held a knife in her hand as she crouched, ready to attack him again.

Prone on his knees, he watched her, fascinated, as she circled him in a bent-kneed fashion and gabbled something unintelligible at him.

“I’ve nae the faintest idea what ye’re saying, lassie,” he said, grinning and rising. She feinted at him with the knife and came at him with a roundhouse kick that was so swift it sent him sprawling on his back. She leapt onto his chest, holding the knife to his throat, and gabbled at him some more.

No longer amused, he put up a hand and grabbed her thin wrist—really there was nothing of her—and twisted until she dropped the knife with a cry. Levering himself over, he squashed her flat beneath him on the grass and, gripping both her hands, he said, “That’s enough!”

She wriggled beneath him, and he discovered that she was definitely female, or at least his body thought so. It had been so long since he’d felt anything resembling desire, it took him aback. Rising to his feet abruptly, he dragged her up and threw her, pack and all, over his shoulder. She shrieked at this treatment and kicked and wriggled and belted him with her fists, but he held her tightly and the dogs came running, barking and capering around him, leaping up and generally making a ruckus.

“Heel!” he snapped at them, and they settled, following him back to the house. This female was one of the accursed Chinese he’d heard so much about. There seemed to be a plague of them suddenly in this corner of the world, all to do, he suspected, with his brother. Since he couldn’t understand this one, and she seemed somewhat dangerous, it would seem to be prudent to lock her up until he could ascertain what she wanted.

Thus, he headed for the steps down to the cellar at the back of the house. Opening the door with one of the keys from the set on his belt, he entered the cellar and opened a second door, to the dungeon, as the boys called it. It was the place the laird, in times gone by, had locked up miscreants until they could be dealt with at council. There’d not been a council meeting since his Grandfather’s day, but the cell was still here.

Passing through the second door, he reached the cell, which was locked off with bars and a door. He dumped his burden on the stone floor and beat a hasty retreat to lock the barred door behind him and then regarded her in the meagre light coming through the two doors from the outside.

She was screaming at him and shaking the bars, reaching through them to try to grab him, but he kept his distance. The cell was grubby with debris and cobwebs, not having been used in a while, and it lacked any amenities. He backed away.

“I’ll fetch ye a bed and blanket and a bucket to piss in!” he said, knowing she wouldn’t understand him, yet compelled to communicate with her, nevertheless. And food, he reflected. She was thin as a reed, a tiny thing, and enticingly feminine in an elfin way that made him think of how the seelie folk might look. He shoved that last thought away; it was disloyal to Cat to think of another woman as comely. No one could hold a candle to Cat’s lush, dark beauty.

He had loved Catriona McTavish from the moment he set eyes on her. It had taken him six months to win her heart and her father’s permission to wed, and he had considered himself the luckiest fellow in creation. They’d had seven wonderful years together before she was taken.

He returned to the cellar and entered the house via the stairs that lead up to the kitchen, where he found Angus skinning rabbits. For rabbit stew, again.

“We have a guest in the cell downstairs,” he said.

“Aye?” Fergus left off skinning to scratch his white beard with one bloodied hand, leaving a red mark among the whiskers. “What’s he done?”

“She,” corrected Col. “I’ll need a mattress and some blankets, a bucket, and some food and drink.”

Fergus goggled at him. “Ye can’t go around lockin’ up lassies, milord!”

“She’s a foreigner. One of those heathen Chinese,” he said. “Tried to attack me in the park and slit my throat.”

“Oh well, in that case . . . ” He scratched his beard again. “There’s the mattress we made up fer yer brother and his wife in the daffodil suite.”

“Good idea, I’ll fetch it down.”

“Why ye going to keep her here? Shouldn’t ye hand her over to the magistrate?”

“I want to know why she’s trying to stab me. It’s something to do with Merlow, I’d stake me bollocks on it. But I cannae understand a word she bluidy says. I want to figure it out.”

Fergus shrugged and went back to skinning.

“Leave off that for a minute and fix her a tray of food and something to drink. That is, if we have anything but mutton? Those chops last night nearly broke my teeth.”

Fergus sniffed, offended, and went to wash his hands in a bowl of water. “Yer tastes been spoilt by yon lassie of Merlow’s. Ye didn’t used to complain.”

“Ye’re right, Fergus, the lass was a fine cook.”

“Well, ye can always put me out to pasture and hire some young flibbertigibbet from Dysart,” he said grumpily.

“Nae, Fergus, I’ll nae do that. We don’t need women here upsetting everything. Look what havoc Hetty caused in just a fortnight. The boys ha’ nae been the same since she left.”

“Aye well, they miss their mother.”

“Hmph. Don’t we all.” Col stomped upstairs, not best pleased to be reminded of the obvious.

The daffodil suite, as Fergus had called it, took its name from the yellow wallpaper and hangings put up by his mother almost thirty years ago. They were faded and dusty now, but the name had stuck. It was still the most elegant room in the house, the furniture being delicate and refined, unlike the heavy dark wood of the rest of the place. He opened the curtains to see and hauled the coverings off the bed, folding them haphazardly. Then he dragged the mattress off and slung it over his shoulder, and with that and the blankets and pillow, headed back down to the kitchen.

Fergus had prepared a tray, and it was sitting on the kitchen table.

“Ye want me to bring it down?” he asked.

“Nae, I’ll fetch it in a moment.”

“Anybody’d think she was a guest, you waiting on her and all.”

“Well, she is of sorts. I daren’t let her out, she’d be off in nothing flat I suspect, or try to attack me again. I’m not sure which. I mean to find out what she wants. There must be a way to communicate with her.”

“Aye, well good luck with that. By the by, Master Callum’s a mite sore and sorry for hisself this morning.”

“And so he should be. Did ye see what he did to Rory’s buckler?”

Fergus raised a tufty white eyebrow.

“Dug a bluidy great gouge through it!”

“He never!” gasped Fergus. “Well, I hope ye tanned his hide good and proper!”

“I did, much good it will do!”

Col humped the mattress on his shoulder and set off for the cellar. Squeezing through the door with the mattress, he found his prisoner sitting on the floor with her legs crossed in a strange fashion, but she leapt up at sight of him and began jabbering again. He ignored that and unlocked the cell door, shoving the mattress through and effectively blocking the door. He pulled it shut behind him and threw the mattress on the ground, which caused a great cloud of dust to blow up, making both of them cough.

“Sorry,” he wheezed, covering his face. “I’ll bring a broom down. Here this is for you.” He spread the blankets over the mattress and dropped the pillow on top. All the while, she stood watching him with a puzzled frown. He waved at the pile of linens. “All yours, I’ll be back with some food in a wee while. Bide a bit.”

He left the cell, locking it behind him, and tromped upstairs to get a bucket, a broom, and the tray. He brought these down and found her sitting cross-legged again, but this time on the mattress. Like before, she sprang up as soon as he appeared, but this time she watched in silence as he set the tray of food down beside the mattress and set about sweeping with the broom. He set the bucket down in the corner.

“To piss in,” he said, squatting and hoping she got the point.

Sweeping the dust and debris into a pile, and using the head of the broom to get rid of the worst of the cobwebs, he backed out and left her to it. He’d give her a bit of privacy to settle in before he began his interrogation.

He needed a wash and change of clothes; he’d slept in them all night, and he felt seedy. To say nothing of some more water and something to eat.

Fullepub

Fullepub