Chapter 3

Rose felt rattled; she needed time by herself.

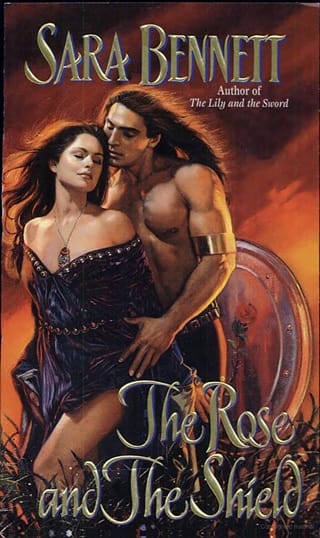

Captain Olafson had upset her in ways she did not understand—did not want to. He was a cold and dangerous savage, and on the outside she had responded to him warily. And yet, underneath, her senses were quivering like a harp’s plucked strings. As if something unseen were happening between them, deep below the surface. As if, thought Rose shakily, the raw, sensual power of the mercenary had found a willing partner in her.

She was more than rattled; Rose was afraid.

Aye, she needed time alone.

Slowly, she began to climb the stone stairs to her own private chamber—her solar. The solar was a Norman lady’s sanctuary, the place where she could be alone or with her ladies, where no one must disturb her without her permission. Edric had given her her solar.

When he and Lord Radulf had built Somerford Keep, they had built it of stone. Stone keeps were still a rarity in England, especially on the smaller manors. But Somerford was unique, standing as it did on the very edge of the vast Crevitch estates, and abutting the lands of two other very powerful barons.

Lord Radulf had felt a stone keep was as necessary as a stout wall, and Edric had been eager to please his overlord, not least because he stood in awe of him. The cost of the building had been enormous, and Radulf had supplied the stone and workmen, and asked for additional costs to be sent to him. But Edric was an elderly Saxon husband with a young, noble wife, and he had wanted to indulge her. He had insisted she have a solar in the new keep, a private room for her own use. And he had insisted that he would pay the extra expense of it—and this had turned out to be more than he had ever imagined, but he had never blamed Rose.

Edric, in his sixtieth year when he died, had been a kind and courteous man. Rose knew she had been lucky in him, luckier than her own mother.

Rose paused halfway up the stairs, her hand on the cold wall.

From early childhood she had watched her mother’s wild and destructive love for her father, watched him take pleasure in hurting her with his indifference, watched all that vitality slowly wither and die. When it came time to have a husband of her own, Rose had been terrified. Not for the usual reasons expressed by other young girls—that he might be cruel or he might be old or he might be mean. No, Rose’s real fear was that she might fall in love with the man chosen for her. It was love that ruined lives, love that could ruin her life, just as her father had ruined her mother’s life.

But Edric, a wily Saxon widower looking to please his new overlords by taking one of their own for wife, wasn’t a man to inspire passionate love. He had never made her burn for him, not even a little. He had consummated their marriage matter-of-factly with only a slight discomfort, and for that Rose had been grateful, as she was grateful for his easy kindness and consideration, and the pleasure he found in her conversation and company.

A shy and gentle girl who had grown up in a frightening and violent household, Rose had entered into her marriage well trained as a housekeeper but with few other skills. It was Edric who gave her the confidence to grow into her position as the Lady of Somerford. And as time passed, she realized that despite what her father and mother and brother had told her, it was in her power to control her own destiny. When Edric died last year, Rose discovered the courage to rule alone.

Now, once more, she felt the old fear stirring.

Not just because of the problems they were having with the merefolk, although these were certainly troublesome. Not because of the lack of money, although this kept her awake at nights. Not because Lord Radulf, as her overlord, could take Somerford Manor from her, his vassal, if she displeased or failed him. Edric had sworn fealty to Radulf, as had Rose, but that did not make Somerford Manor entirely secure—she tried not to think of this. And not because the mercenaries she had hired to solve their problems with the merefolk were so much more…more savage than she had imagined—Arno had been right there, they were no tame cats to stroke and pet.

No, Rose was afraid of herself.

Afraid of what was lurking in her soul.

That in some secret chamber within, a hidden room of shadows, was a deep, dark, emotional well, just waiting to be tapped. And once broached, the black waters would rush out, unstoppable, drowning her, destroying her, just as her mother had been destroyed in the same flood. Breathless, she remembered again that dizzy, heady feeling she had experienced in the bailey when she first saw Captain Olafson. The thump of her heart, the tremble of her legs, the tightening in her belly…

Such a thing had never happened to her before, and she would not allow it now. Rose straightened her back, lifted her chin, and took a deep breath of the chilly, damp air in the stairwell. It cleared her head. Mayhap this had been a momentary thing? Some problem with the phase of the moon and her monthly cycles? For how could she even contemplate making wild, passionate love with a rude…heartless…conscienceless…Viking savage?

When Rose reached the solar she found it was not empty as she had hoped. Constance sat on a stool mending a well-worn linen chemise, diligently attempting to prolong its life. New clothing was becoming an urgent necessity, but Rose did not feel she could buy for her own back when her people went without. After the harvest, she hoped for the hundredth time, there would be coin and more for all that.

Constance was staring up at her, old eyes sharp with curiosity. “Have you spoken to the mercenaries?”

“I have.”

Rose wouldn’t meet her gaze. “Sir Arno is taking them to stable their horses. They will probably eat their heads off.”

Constance’s lips twitched. “The horses, do you mean? Or the mercenaries?”

“Both!”

Rose gave the old woman a suspicious glance; Constance was showing uncustomary restraint.

“Mayhap you should go and show their captain his sleeping quarters. See to his bath,”

Constance went on, and now her voice trembled with the effort to keep it disinterested. “Do you think we have a tub big enough for him?”

“I doubt it,”

Rose replied dryly. “Have you had your fun now? I take it you saw him? Captain Olafson?”

All pretense vanished. Constance’s eyes gleamed like pale jewels. “Indeed I did, lady! A Viking god.”

Rose shook her head, wondering as she did so whether she was trying to convince Constance or herself. “The man may be a god, but he is also a savage. An unfeeling monster. He has no heart and no soul. If you think he is the new husband you are always seeking for me, old woman, then you are very, very wrong.”

Constance had listened to the tremble in her lady’s voice with growing trepidation. Something had upset her badly. She had not seen Rose so shaken since the day Edric had had to order the lopping off of one of his serf’s hands for stealing, and that was after he had let him off with a reprimand two times.

“But he is so fine-looking!”

she wailed, laying aside the once-fine linen chemise. “How can a man who looks like that be so black inside?”

“I don’t know,”

Rose said grimly, “but believe me ’tis so. His soul is like a raven’s wing, and as putrid as a midden. Content yourself with looking at his face, Constance, for that is the only pretty thing about this man.”

Constance sighed and remained silent as Rose sat down.

“Six marks,”

her lady muttered darkly. “And food and lodging! Well, let us pray they are worth it. But I fear they will be nothing to me…us but trouble.” Impatiently she reached up and removed the metal circlet that held her veil in place on her head, putting both aside. Her strong, dark hair was plaited into submission in one long, thick rope that tumbled down her back, while glossy raven tendrils curled about her flushed face. “I wish now I had never asked Arno to find me these mercenaries!”

“Where did he find them?”

“I know not—some knightly friend, he said. I left all such arrangements to him. Oh, I should have dealt with it myself!”

“You are in a fine temper,”

Constance said dryly.

“I am weary,”

Rose replied, and knew it was so. The Lady of Somerford must be hard, she must be tough. She must sit at the manor court and make judgment upon those who transgressed, who did not pay their rent or neglected their duties to the manor; she must order men to fight and mayhap die; she must rule in cases of stealing or assault or even murder. She must make the decision between life and death, and do that every day.

But Rose had been born with a gentle heart, and in such circumstances as these to have a gentle heart was the worst of all possible afflictions. And yet it was her gentle heart that had endeared her, a Norman lady, to her English people.

After Edric died, when it would have been so easy to give in and let Arno take over Somerford, when Rose teetered on the verge of saying aye, Constance had opened her eyes. Sir Arno did not love and care for the people as Rose did. He meant well, he was loyal, and he might be versed in the practical side of being lord of the manor, but he had no compassion for the English people. Would he set aside eggs for the smith’s sick child, or remember old Edward’s aching bones in the winter and order extra wood to be gathered for his fire?

Of course not! Arno would be more likely to consider a sick child a waste of eggs, and old Edward better off frozen.

Mayhap Arno was right and she was wrong, but Rose could not think so, and she could not live with her conscience if she allowed him to enforce such a regime here at Somerford. So she had gathered her courage about her and ignored the voice in her head—sounding remarkably like her father’s—that told her she could not do it. She resisted the temptation to allow Arno to take the reins, and thereafter insisted all decisions that had formerly been made by Edric were now to be made by her and her alone. Somerford Manor was now hers, and as long as she was able she would hold it and its people safe.

“We are all weary,”

Constance answered, “but there will be time enough to sleep after death. If you want rid of this black-hearted mercenary, go to Lady Lily. She has always supported you. She likes you; she will listen.”

“Lady Lily has troubles of her own, Constance. She is unwell with this second child she carries, and the first still so young.”

“Radulf is a lusty husband.”

Rose frowned. “Then she should have told him nay.”

Constance smiled at her lady’s naivete. “Is that what you did with Edric? And I’ll be bound he meekly went and left you to your sleep. Oh, lady, you do not understand. If you were wed to a young, virile man whom you desired, you would not be able to say him nay, either!”

Rose shifted irritably. How dare Constance speak as though Rose were an ignorant virgin? As if she understood nothing of the relationship between a man and a woman? “’Tis none of your concern, old woman.”

“No. Right now this mending is my concern, so I will say no more, my lady.”

That deserved a reprimand, and Rose opened her mouth to give it.

The shriek was so loud it made both women start.

Younger and spryer, Rose was first to the window. She leaned out just as the shriek came again. It tore through the bailey, which had just begun to resume some normality after the arrival of the mercenaries.

Constance, close behind her, clutched her arm. “What is it, lady? Is someone being killed?”

Rose had thought so, too, but though she scanned the yard frantically, she could see no blood. Then the shriek came again, and this time she spied the child. A young boy, he was swinging by his hands from the wooden gangway that had been built around the top of the ramparts. It was there the guard would stand to keep watch, and there, in times of attack or siege, that the people of Somerford would fire down on their enemies.

The boy was young, perhaps no more than three years old, and his feet dangled over the sizable gap to the ground beneath him. If he let go he would be hurt, mayhap even killed! And from the sounds he was making, Rose did not believe he could cling on much longer.

“Jesu, no,”

she breathed, one hand pressed hard to her quaking heart. Then, to the people standing about below, “Help him! Someone…please…help him!”

But before anyone could move, the mercenary Captain Olafson, with his men behind him, arrived in the bailey. Rose caught her breath with a squeak; behind her Constance choked audibly. He had removed his chain mail tunic, and his body was naked from the waist up. Hard muscle curved beneath bronzed skin, big powerful shoulders and arms; there was nothing soft about him. Despite the perilous situation, a memory of Edric flashed into Rose’s mind—pale, skinny legged, his once-firm body stooped and sagging with age. The half-naked mercenary beneath her window was a revelation.

I wonder what it would feel like to touch him? Would he be as hard as he looks?

The thought had barely taken shape when Rose realized that, assuming the manor to be under attack, he had drawn his sword from the scabbard at his side, and was holding it before him. The blade was made of black metal and it shimmered darkly as he turned four feet of violent death expertly in his hands. He was very frightening. Terrifying in an elemental way. And the fascination she had felt upon first meeting him returned tenfold.

Dangerous he might be, but Rose wanted him with a deep hunger she hadn’t known she possessed.

People were scattering out of his way. Geese ran honking, and a young goat skittered about on thin legs. A woman fainted, dropping her basket of eggs. They broke in a puddle about her feet, and one of the hounds gave up chasing the geese to lap greedily at the yolks.

Before Rose could do or say anything, the mercenary had grasped the situation and was again sheathing his weapon in the intricately carved scabbard at his side. The child screamed once more, stubby bare legs kicking wildly in the air. That was when, in a rush, Rose realized that everyone below her was either too afraid or too stunned by the sight of the mercenary captain to go to the little boy’s aid. She opened her mouth to startle them into action.

He had anticipated her.

Captain Olafson was striding forward, looking so big and capable among the helpless onlookers. He reached up, just as the boy, with a last lusty cry, let go his hold. The child fell neatly into his arms and, with a rough gentleness that made Rose’s skin prickle, the mercenary checked him for injuries. But the child yelled and began to struggle wildly. He was set down and, with a last wail, promptly took off as fast as he could manage, toward the keep.

“Probably more frightened of his rescuer than by any fall,”

Constance muttered, and shook her head. Her eyes were fastened on the man’s bare chest as if she were a human leech. “Did you recognize the boy? I thought ’twas Eartha’s son.”

But Rose did not answer her. Her hands were gripping the windowsill and she was unable to move, for her gaze was also riveted on Captain Olafson. Her heart was thudding in her ears like a drum. I know him. How can I know him? And yet there was something suddenly so familiar about him, while at the same time he was utterly unlike any man she had ever seen before in her life. A familiar stranger? It made no sense.

Rose took a shaking breath. He hadn’t moved. He stood in the place where the boy had left him when he ran, bare-chested, his copper hair gleaming in the sun, his long legs set apart in the dark breeches that clung like a second skin, one hand resting on the hilt of that terrifying sword. And then, with a movement that for some reason struck Rose as both eager and yet unwilling, the mercenary tilted his head and looked up. His blue eyes found her at her solar window as if he had known her position all along.

He looked straight at her.

It was as if their gazes were flint and tinder. They struck and sparked, setting fire to Rose’s body and mind—a white hot blaze. It made her feel alive! She felt as if she had been asleep until now, a walking sleep, and then in a moment she was wide awake and eager to begin living…

Almost as quickly the impossibility of the situation—and her terrified recoil—sent Rose stumbling back, out of his sight. At the same time he spun on his heel and was walking away, brushing through his men in a manner designed to prevent comment and hurry them into following him.

Constance’s breath spurted from her lips in silent laughter. “Is that your raven-black soul?”

she asked innocently. “No, no, lady, you are mistaken. I believe you have hired yourself a hero. What think you of that?”

Rose found her voice, though it did not sound like hers. “I think any fool can save a child.”

“Aye, but would he? ’Twas not the mercenary’s place to take charge, and yet so he did. I did not see Sir Arno rushing to the boy’s aid.”

Arno would not do anything so undignified, Rose thought wildly. He was a knight; the child was a cook’s son. There, for Arno, the matter ended.

She moved to warm her hands at the sulky fire. They were shaking worse now and she knew why, though she would never tell Constance. Captain Olafson was the cause. For some inexplicable reason, he had jolted her to the core. In the short time he had been at Somerford he had become the most important thing in it.

No! she thought angrily. That isn’t so. How could it be? He is a stranger, a creature beyond my experience, a man whose life can never really bisect mine…

Why did he save the child?

The question cut through her. Was he really a hero, as Constance said? Then why had he told her that he believed children were expendable in men’s wars? Why had he made her believe he had no heart? Such a man would not then turn around and save a child’s life. A child who had no ties to him. There had to be a reason, one that made sense, not a fantastical explanation like Constance’s.

If she could make sense of it, Rose could turn him back into the savage, soulless creature she believed him to be. And if she could do that, then mayhap all inside her would be calm again. Suddenly she craved normality.

“I had best get down to the kitchens,”

Rose said, as if her heart were not jumping about like a landed fish in her chest. “Eartha and the other women will need help. There will be much food to prepare—I imagine these mercenaries will eat more than all of us put together! I wonder if we should kill one of the pigs we have been saving for bacon?”

And she was gone before Constance could answer.

The old woman plumped down by the fire and stared into it. She did not need to be a seer to know that the big mercenary frightened Rose. Was it his strength she feared? His occupation? Or his maleness? Certainly Constance had never seen a man before with such a blatant attraction for women—witness him in the bailey just now! The air around him had actually sizzled with the promise of sexual fulfillment.

But was he capable of delivering on that promise?

Constance sat, thoughtful, as the fire spluttered and distant sounds drifted up through the open window. Whoever and whatever he was, if this man would save a child when no one else seemed capable of it, then it was plain he was a better man than Sir Arno. Surely that was all that really mattered in the struggle to come? And, aye, there would be a struggle. Constance might not be able to see into the future, but she knew that much.

There was trouble brewing, and whoever won the battle would take Somerford Manor.

And the Lady Rose.

Ivo downed his ale in one gulp, but his dark eyes were watchful over the rim. Gunnar sat on the bench in the corner while around him his men laughed and shoved and claimed their own sleeping spots. And yet he was very much alone.

Their captain had been much subdued of late. Not that he lacked as their leader—there was a solid core of steel strength inside Gunnar, a calm stillness. If Gunnar told them he would do something, then he would. He was utterly dependable.

Before Somerford, Gunnar and his men had been on the Welsh border, the Marches, where they had fought in the name of some chinless Norman baron. They had earned their money that time, Ivo thought grimly.

The Welsh had been hidden in the hills and the forests, waylaying the unwary, silent and deadly with their longbows and arrows. Gunnar’s men had proved their worth again and again, but Ivo had sensed Gunnar’s distraction.

The chinless baron was greedy, stealing land that was not his own.

“Why,”

Gunnar had said, “should we support a man such as this? Give our lives so that he can look out at the view from his window and say, ‘This is all mine’?”

“It is our job,”

Ivo had retorted. “Do not think beyond the doing, Gunnar. It is dangerous for a mercenary to question too hard.”

Aye, Wales had been a dangerous place. More than once Gunnar’s warrior instincts had kept them from being skewered like pigs. And with each close call, Gunnar’s melancholy had seemed to deepen. One night they had drunk deep, and it was as if the silent, calm Gunnar had sprung a leak.

“I do not want to end with an arrow bolt in my eye like Harold Godwineson,”

he’d said. “I don’t want to die where no one knows me or cares.”

“What other course is open to you?”

Ivo had joked uneasily, hoping to jolly him up a bit. This was not the Gunnar he was used to. He, Ivo, was the emotional one; Gunnar was always so tranquil, so untouched by the turmoil about him. “Can you become a farmer with a plow? I do not see you rising, shivering in the dawn light, to plant barley and peas. Though I can see you cuddling against a plump lusty woman, plowing between her thighs.”

But Gunnar didn’t laugh.

“Maybe you could be a weapon maker like your sire,”

Ivo went on quickly, “forging great swords for great warriors and weaving chain mail for Lord Radulf.”

Gunnar blinked like an owl.

“But the truth is, my friend,”

Ivo had told him softly, encouragingly, “you are so good at being what you already are.”

“Aye, you have the right of it, Ivo. I am no use for anything but fighting and killing. Where does a mercenary go in his old age? Better I die now, here, and get it over with.”

And then he had murmured beneath his breath, the slurred words meant for him alone. “Is there a place for such as me, where I can be valued, honored, and loved?”

Ivo had clapped him hard on the shoulder. “You’re not old yet, Gunnar! Plenty of work and women left in you!”

And eventually, after a few more drinks, Gunnar had agreed that he was right.

Now Ivo poured himself more ale, watching Gunnar pretending to listen to Sweyn’s jokes, and remembering that drunken night. The next morning, as if wishing had made it truth, there had been a message from Radulf. They were needed at Crevitch—there was treachery afoot. Gunnar had been exhilarated ever since—or as exhilarated as a man like Gunnar could get.

Land. Somerford Manor. It was Gunnar’s to take when he had accomplished Radulf’s mission—proved the lady was in cohorts with his enemies as her letter suggested. Once that was accomplished the rest of them could stay on with Gunnar, or take their share in coin and move on.

From a distance it had sounded so simple.

But nothing was easy and despite his profession and his ability to lie seamlessly, Gunnar was a deeply honorable man.

Ivo said a silent prayer: Let Lady Rose be an evil, treacherous bitch. If that were only the case, then all would be well. Gunnar would take Somerford with a clear conscience and make his life there, live to a ripe old age a happy man. The warrior would have found the haven he had been secretly longing for.

But Ivo feared the lady was not quite as they had believed. She was beautiful for a start, although Gunnar had had beautiful women before. She was a Norman lady, but there had been a few well-bred ladies who couldn’t keep their hands off Gunnar, and they had never slid under his guard. In fact, Ivo could not remember a single woman who had meant more to him than a warm body or a pleasant few hours.

Unwilling, he let the memories of the more recent past well up in his mind. The look on Gunnar’s face as Lady Rose walked across the bailey toward them, as if he’d been struck by a bolt of lightning; how she had stepped around the Norman knight, placing herself directly in Gunnar’s line of sight while Gunnar had been trying very hard not to look at her; and just now, when he looked up at her window—Ivo had felt the heat coming off him in waves.

Aye, Gunnar wanted her. ’Twas a pity she had come along at this time, when there was so much more at stake. Just when Gunnar was at his most vulnerable. When she could quite possibly destroy his whole happiness.

Fullepub

Fullepub