Chapter 73

73

Inside the house we all used to live in, there is one pair of shoes at the door. The kettle perpetually steams. I use the same water glass six times before I wash it. I break dishwasher tabs in half. The hangers in each closet are spaced two inches apart and there’s nobody here to move them. There are splotches of tea on the hallway floor that I haven’t yet wiped, although I think about doing it every day. I put inordinate importance on organized drawers, and the plants are overwatered. There are forty-two rolls of toilet paper in the basement. I nearly always forget to remove this item from the list of groceries I reorder every other week online.

I hope for a mouse, and I know this is strange, but I often yearn for the comfort of a regular visitor, the crinkle of a bag in the cupboard or the scatter of claws on the hardwood; brief, nonverbal, predictable company.

On some weekends, I turn on the Formula 1 races. The pitchy hiss of the engines and the British commentary take me back to Sunday mornings before swim lessons, when I’d bring you eggs and coffee, toast without the crust for Violet.

• • •I’ve grown used to the loneliness, but there was someone who only came over when Violet was at your house. He was a less than successful literary agent whom Grace introduced me to. He liked to fuck me slowly with the bedroom windows wide open, listening to the footsteps on the concrete of the sidewalk. I think feeling close to the strangers outside made him come faster.

I’m starting with that, but it won’t make the right impression. He was measured and intelligent, and he was a reason to cook at night, to open a bottle of wine. He used up the toilet paper. He added warmth to the bed when I needed it on occasion. I liked the fact that he never asked about Violet—they didn’t exist to each other. I hadn’t met a man who was easier to be around, in that sense, than he was. He didn’t like to think about the fact that I had children—that my body had birthed and had fed. You thought of motherhood as the ultimate expression of a woman, but he didn’t; for him, the vagina was nothing other than a vessel for his pleasure. To think of it otherwise made him physically queasy, the way others felt when they gave blood. He told me this once when I told him I had an appointment for a Pap smear.

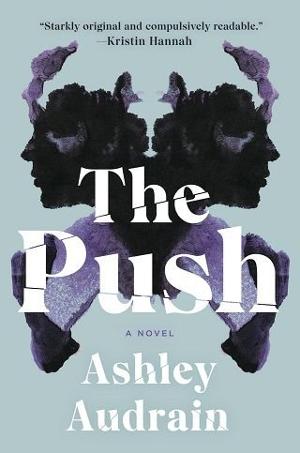

He read my writing and we talked about what I could do and what could sell. He wanted me to write young adult, something commercial and angsty that would work with the right cover. Something, in other words, that would work for him to represent and monetize. Sometimes I wondered about his motives, in that respect. But I was on the cusp of the age when women worry about disappearing to everyone but themselves, blending in with their sensible hair, their practical coats. I see them walk down the street every day as though they’re ghosts. I suppose I wasn’t ready to be invisible yet. Not then.

Fullepub

Fullepub