Chapter 34

34

The mother was dressed in the same yoga clothes she always wore at drop-off, her shirt slightly wrinkled from the hamper. Her hair was leftover from the previous day’s effort. Her son stood next to her and pulled his baseball cap off. The schoolyard was electric with morning energy, tummies filled with Cheerios, faces plump from sleep. She crouched. He found his spot in her neck. I could see from where I stood that there was pain in the boy’s face; her hands closed around his head like the petals of a flower. Her mouth moved slowly in his ear. He coiled into her. He needed her. Behind him noise grew, shouts, the whip of basketball rubber on cement.

She slipped her hands down his slight shoulders and he pushed away, his small chest rising, but she pulled him back again. It was she who needed him this time. Now, her face in his neck, three seconds, maybe four. She spoke again. He squeezed his eyes. He nodded, put his hat on, pulled the brim low, and walked away. Not slowly, not with hesitation, but with anticipation, with haste, on legs that turned in slightly at the knees. She could not watch, not this morning. She turned away and left, looked down at her phone, and got lost in something that didn’t make her ache in the way her son did.

My belly fluttered like a net of butterflies for the first time that morning. The baby was waking inside me. Violet had left her bag of orange slices with me at drop-off and I sucked the warm juice from them, tossing the rinds in a city garbage can as I followed the mother down the street and through two intersections. She stopped for salt from a corner market and I watched her from behind the pyramid of tomatoes. I wanted to see her face. To see if she carried him with her. I wondered how it looked—how it felt—to have that kind of connection to another person. I hadn’t yet found the answer when I lost her one block later in a crowded section of sidewalk construction.

These kinds of things happened around us, Violet and me, in a language we did not speak. So I was desperate to learn. To be better with the one who came next.

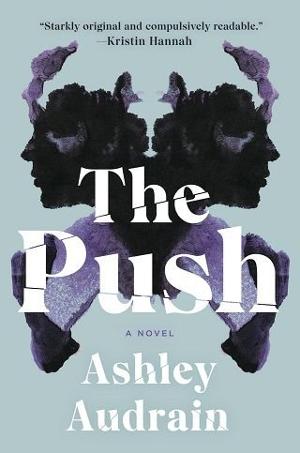

On the way home, I walked by a woman setting up a small flea market stand on the side of the street. She leaned a stack of old paintings against the lamppost as she put colored dots on the backs to mark the prices. She pulled out one in an elegant gold frame and looked at it thoughtfully, deciding how to price it. I stood behind her and found myself clutching my chest as I took the painting in. It was of a mother sitting with her small child on her lap, the rosy baby dressed in white and cupping his mother’s chin gently as she glanced down. One arm was around the child’s middle, and the hand of the other held his small thigh. Their heads touched. There was a peacefulness to them, a warmth and comfort. The woman’s long, draping dress was a beautiful peach with burgundy florets. I could barely speak to ask her the price. But it didn’t matter—I had to have it.

“I’ll take that one,” I said as she put it back in the pile.

“The oil?” She took her glasses off and looked up at me.

“Yes, that one. The mother and the child.”

“It’s a replica of a Mary Cassatt. Not an original, of course.” She laughed as though I should know how absurd it would be to have an original Mary Cassatt.

“Is that her in the painting? The artist?”

She shook her head. “She was never a mother herself. Maybe that’s why she liked to paint them so much.”

I carried the painting home under my arm and hung it in the baby’s nursery. When you came home that night to find me straightening the frame on the wall, you stopped in the doorway and made a noise. A humph.

“What? You don’t like it?”

“Not your typical nursery art. You hung pictures of baby animals in Violet’s room.”

“Well, I love it.”

I wanted that baby. That cupped face. That chubby hand on mine. That palpable love.

Fullepub

Fullepub