Chapter Twenty One

Over the next two days, Polly’s carefully wound composure began, slowly, to unspool.

She held it together for Toks.

Friday was a slow, casual, relaxed day as Toks mentally prepared for the evening’s concert. Polly lay in bed, tangled in the sheets, barely anything covering her on a warm spring day. Toks padded around the apartment in loose, soft pants, a shirt hanging open. She played the Steinway and coaxed Polly out of bed with a lunch of pancakes, raspberries and fresh cream. By late afternoon, she was deep in the score of the Ravel, sitting in a window seat, the sunlight in her hair. Polly kissed the top of her head, and Toks buried her face in her belly for a moment – then her eyes drifted out of focus and she hummed the horn line.

“They’ve always been a bit hesitant on that entry,” she murmured, and scribbled something on her score in blue pencil.

It was exactly the life Polly had always imagined they’d be leading, though they’d both pictured Polly rehearsing too, running through the cello part, working out last minute kinks.

It should have been pre-show nerves twisting in Polly’s stomach. Not this.

By early evening, and still so buoyant and heart-clenchingly eager for Polly’s approval, Toks linked Polly’s arm in hers and led her across the Kjarta Harmonja to the Dom, her scores in a leather satchel over her shoulder. It should have been perfect, but the closer Polly got to the concert hall, the more she felt like throwing up.

To her immeasurable relief, Toks walked them not to the main entrance, but to the stage door. She signed her in with a friendly chat with the security guard. Her Korovinjan was perfect, or at least Polly supposed it was, because the guard and the others on duty laughed at her jokes, one even offering her a high five and good luck for the performance.

They met Sumi in Toks’ office and dressing room, an extravagant space compared to rooms they’d used in other venues across Europe, and definitely a few steps up from her office in the Sydney Opera House. Sumi had Toks’ performance clothes laid out for her and a dress bag for Polly.

“But I didn’t—” Polly began, and Toks shushed her with a kiss.

“I bought you a little something,” she smiled. “Okay, a few little somethings— Sumi, where’s the jewellery? Thank you. Come back at the fifteen minute call.”

Toks’ swagger was rising with each moment, and by the time she was tucking and tying herself into a tux complete with white tie and tails, she was almost transcendent. She zipped Polly into an absolutely stunning gown in emerald silk and wouldn’t hear her protests.

“You’re beautiful,” she breathed into Polly’s neck and clasped a necklace to her throat. “I don’t think I’ve ever been happier – having you here, in this place. Oh, my darling Pearlie, everything I do, everything I have is for you. You know that, right? I want to spend every second of my life making up for the sixteen years we lost.”

So, how could Polly tell her after that? How could she tell Toks all she wanted to do was run from this building as fast as she possibly could? And keep running, all the way to the other side of the world, til she was home. Safe.

She would be brave. For Toks. She hitched her best smile onto her face – which was easier than she thought with Toks looking at her like that – and kissed her for luck.

“I don’t need luck,” Toks said, that adorable tease hovering at the corner of her mouth.

“You’ve got ego instead.” Polly knew her line. She whispered it against Toks’ lips and shut her eyes, wishing the strong fingers around her waist could save her from what was coming.

“I’ve got you.” Toks kissed her, then pulled away with a tiny frown. “Is everything okay, Polly? You look—”

But she was saved by Sumi’s perfect timing, as the woman returned to lead her through the maze of backstage corridors to the red carpeted foyers of the cathedral of music where the torturous memories of sixteen years ago waited for her on the main stage.

Violet’s British musician friends were Marc, Luka and Jak, and none of them had ever seen a war zone up close and personal before.

“It’s so much worse than I thought,” Violet murmured. She had a faded photo of her parents taken when little Violet was a babe in arms. They were standing in the sunshine in front of a magnificent palace, fashionable 80s shoulder-pads and big hair, and eyes bright with optimism. Violet wanted to visit the same place and take a photo to send home to Australia.

They hadn’t counted on the burnt out cars and bombed tanks littering the avenue.

“Maybe we’ll come back in a few weeks,” she said.

Their taxi driver swerved around the tanks like they were nothing special and muttered something in Korovinjan Polly didn’t understand.

“Or months,” Violet added.

But the five of them worked wonders together at the music school. It was in a residential area of Severin, half an hour from the city centre and two decades of neglect had reduced the place to a tumbledown wreck. The street-to-street fighting over the last few months had scared most of the students away and a tank had barreled through an outer wall, but the situation wasn’t unsalvageable.

Polly rolled her sleeves up and got to work cleaning old music classrooms, tearing old newspaper down from the windows and making things bright and new. Students came back the very next morning, and by lunch they had enough for a small band. Music really was a universal language. She sang nursery rhymes with the small kids while their parents pitched in to help. The teens stood sullenly on the edge of the activity and rolled their eyes at the adults playing folk tunes and classics by a long-dead Korovinjan composer. Violet won them over with a Nickelback song by evening and someone’s grandmother made a hotpot and, for a short time, everything was right with the world.

“We’re really rebuilding a community with music,” Violet enthused.

It was hard work – confronting but worthwhile – and even if the phone signal hadn’t been intermittent and unpredictable, Polly was too tired to call Toks anyway. She knew now her romantic dream of arriving at Berlin Hauptbahnhof with a handmade Korovinjan trinket especially for Toks had been foolishly naive. Instead, she concentrated on throwing her heart and her back into rebuilding the school. Perhaps one day, when she and Toks both had a holiday from their orchestras in Berlin, they could come and visit the new peace in Severin and Polly could show her what she’d achieved. Toks would be proud.

They had three wonderful days at the music school before they all decided to visit the rest of the Aussie-Korovinjans from Sydney who were working across town at an orphanage.

And that’s when everything went wrong.

They were squashed in a taxi, laughing, too full of their own success to pay any attention to the tense mood of their driver when six members of Ratimir Vass’s personal army ambushed them in a street not too far from the city centre. Two black SUVs, peppered with gunshot, appeared out of side streets, one at the front, one at their rear, and even then it took them too long to realise this was a planned operation.

“Someone should tell them they lost,” laughed Marc, but their driver snarled at them. Whatever he said made Violet blanch and Luka giggled nervously.

“Who—” began Polly, but there wasn’t time. The soldiers were out of their vehicles, guns – actual machine guns – in their hands.

Marc got out of the car. The driver hissed at him. Violet clutched at his clothes, but Marc had the confidence of a twenty-five year old blond male who’d spent his life smiling his way out of trouble. He was going to explain. He was going to smooth things over. He was a nice guy.

A Securitate soldier shot him right between the eyes.

Polly didn’t understand until months afterwards, but the Securitate had been Ratimir Vass’ secret police and his private army all in one. They’d perfected what the Gestapo, the KGB and the Stasi had only begun, and they weren’t pleased at the order to hand themselves in. Their sole function had been to keep Ratimir Vass and the party in power. They’d never cared how.

Now Vass was dead. The international community was falling over itself to aid the new leaders in free and democratic elections, and they’d issued a polite and generous decree. All members of the Securitate still at large were to report to the prison they themselves had once overseen. Some would face military trials. Even the lowest ranking soldier could expect three years of incarceration plus community service to help rebuild the nation they’d destroyed.

The West thought it was a good deal.

The Securitate didn’t see it quite the same way, and a handful of British and Australian hostages would strengthen their bargaining position.

They didn’t need the driver. One of the soldiers barked at him in Korovinjan and he turned and ran without a second glance at Polly and the others. They shot him in the back just as he reached the footpath.

They left both bodies in the street.

Violet started an awful high-pitched wail that went on and on as they were all pulled bodily from the car. A soldier smacked her face, once, twice, and then jammed the butt of his rifle against her jaw when she didn’t stop.

A million things crystalised in Polly’s head. The glorious blue-sky morning and the crisp winter air on her skin. The knowledge that running would kill her and that fighting back would hurt. That life is nothing but luck and sometimes it’s just bad. And that she loved Ksenia Tokarycz with every atom of her being and would never see her again.

They zip-tied their wrists and feet, pulled bags over their heads and man-handled them into the SUVs. A short, violent drive later and they were dragged out again, into a building with the feel of carpet beneath their feet, tugged by the arm down a slight slope, her leg banging repeatedly on hip-high obstructions. Then a short set of steps. Then thrown onto a wooden floor.

There was a strange humming sound in the air – a splash of frequencies – that rang and swelled with every footfall, with every incomprehensible order.

When the bag was finally ripped from her head, it all made sense. They were on a stage in the centre of what had once been a grand old concert hall. The dome above their heads was open to the sky and debris littered the stage and auditorium. Velvet that had once been a rich, wealthy crimson was grey with dust and decay.

A grand piano knelt, broken and cowering, in the middle of the stage. One of its legs had been smashed away and its upper register kissed the dust. Its lid was smashed and its pedals were jammed, its dampers opening every string and setting them vibrating with every sound.

Violet cried. The piano echoed her.

A soldier shouted. The piano boomed.

The man in charge shot the air and the piano roared, howling its agony into the empty auditorium, swirling up through the bomb-hole in the dome and out into the Korovinjan winter.

Polly closed her eyes, gritted her teeth and … waited.

“I’ll take you through to the west foyer,” said Sumi. “Nikoloz and Artis are there. You’ll be sitting with them in their box to watch the concert.”

Polly followed Sumi’s brisk stride and concentrated on her breathing.

Of course, the Dom Harmonja was beautiful now. Sixteen years of peace and wealth had perfectly restored its elegance and once again it was the jewel of the Danube. The gently curving foyers were a forest of tall marble columns, vaulted ceilings rich with gold filigree. Frescos high above their heads were painted in cream, muted greens and russet. Severin’s finest were just as stylish, milling with champagne flutes in their hands and laughing.

The sound of it buzzed in her head like a nightmare.

She nearly stumbled at the sight of a vast banner hanging from the ceiling advertising the orchestra and the current concert series. It was a picture of Toks in mid-performance, vivid in a pristine tuxedo and crisp against a jet black background. That straw-blond hair fell over one eye but the other shot a piercing gaze at the viewer. One hand stretched out before her – an imperious gesture that was part order, part invitation – and Polly’s eyes stuck on her fingers.

Sumi caught her looking. “As if her head wasn’t big enough already, right?” She laughed.

Polly managed a tiny smile.

Artis was waiting for them, four champagnes clutched between his hands and a faux-irritated frown on his face. “The problem with being in love with someone famous,” he said, cheerfully. “Niki is off being charming somewhere and I’m holding the drinks like the hired help.” He tilted his head and rolled his eyes at the banner of the maestro and gave Polly the grin of a co-conspirator.

Sumi blew a raspberry. “One of those for me?” She took one anyway.

Polly was glad for their easy chatter. She was unravelling, moment by moment, and it took everything she had to hold herself together. It took her mind off what was coming. She was going to have to walk into that auditorium and watch Toks on that stage.

That stage where…

It was okay, she told herself. She could do this. The Boulanger went for thirteen minutes, the Vaughan-Williams for forty-one. That was nearly an hour before they’d roll a piano on the stage for the Ravel, and Polly needed every second to steel herself against that.

Artis downed one of the champagnes and dumped the glass on a nearby table. He started in on the other. “I guess Niki will join us in the box.” He hooked his spare arm into Polly’s and switched into genial host and tourist guide mode. “Did you know this gorgeous old dame of a building has been bombed in every single war since Napoleon? There’s a display over here. Come and take a look.”

Oh fuck. Polly’s pulse was beating in her ears. Please not pictures from the revolution!

They started at the other end of history. Etchings of the building in construction in the 1700s. A painting of French soldiers in dark blue tailcoats with red plumes on their hats charging on horseback over a bridge on the Danube, smoke billowing from the dome of the Dom Harmonja in the background. Grainy sepia photographs of a woman in a cloche hat cutting the ribbon on another restoration. The devastation of Allied bombing in the final days of World War Two.

But there was something much worse than a photograph of the Dom in the revolution.

Polly squeezed Artis’ hand. She didn’t know when she’d grabbed it, but she stumbled too. She didn’t see Artis’ panicked gesture to Sumi who came and stood at her other side, a kind touch on her shoulder.

“Polly?”

Her entire existence pin-pointed down to a small dark circle immediately around them. The cacophony of two-thousand happy voices waiting for the bells to ring flattened into a hollow silence.

In front of her, on a podium bounded by red velvet ropes, was a ruined piano.

It was the piano.

The one that had haunted her for sixteen years.

“Polly?”

It was still on two legs, tilted into the ground. It was clean now, wiped free of dust and blood. It had even been polished, she realised, incredulously. And it was silent. It was… dead.

“It’s a monument,” Artis said, his voice kind in her ear. Puzzled but caring, willing her with all his affable decency to be okay. “A memorial to the war and a testament to the power of art and music to heal and bring people together.”

Sumi’s hand was in the middle of Polly’s back. Her voice was slightly more urgent. “Polly? Are you alright?”

“It was shattered when a mortar fell through the roof of the concert hall in the final days of the revolution. It stayed on the stage all during the hostage incident, when those four British and Australian kids were—” He stopped himself and gaped.

“I know,” Polly murmured.

She blinked, furiously. It was just a piano. It was only ever just a piano.

Artis sounded dazed, but compelled to finish the thought. “—when they were held and tortured for six weeks—”

She dragged her eyes away from the piano and watched realisation dawn on both of them. Artis’ eyes tracked down to the scar on her cheek, to her wrists where the beautiful beaded shawl Toks had bought her revealed her arms. She could see Sumi running calculations in her head, counting years, reassessing everything she knew, her face crumpling with the horror of the impossible.

“Only one of them survived,” murmured Artis.

“I know,” whispered Polly.

“An Aussie girl.”

“I know.”

“Nikoloz was—”

“I know.”

Sumi accepted the truth of it first. “God, Polly. Are you okay being here? Is there anything I can do? Anything you need?” She peeked at her watch. “We still have ten minutes. Do you want me to get Toks? Do you want—” Her eyes narrowed and voice hardened. “Fuck, does Toks even know?”

“No!” Polly sucked in a breath, clearing her head. She was fine, it had been sixteen years, and she’d worked through all this shit ages ago. She was a strong, capable woman – a survivor, for fuck’s sake, in every ugly, literal sense of the word – and she could do this. She didn’t want her trauma to be a drag on Toks’ happiness. She didn’t want it surfacing to threaten her own happiness. “No, she doesn’t and I don’t want her to. I’m fine. Really. It’s just the shock of seeing this again.” She wasn’t fine but she was going to do this for Toks. “Don’t disturb her. She’s just about to step out in front of the orchestra.”

Sumi looked doubtful, and Artis opened his mouth to protest, but the bells rang and the doors to the auditorium opened.

“I’m perfectly okay,” Polly said again. “Shall we go in?”

She was proud of how steady her voice sounded, of how convincing an act she was putting on. Her calm tone worked on Artis like a charm and he found his gallantry and held out his arm. Sumi watched with a worried expression.

She followed Artis into the dark, richly carpeted passageway to the concert hall’s boxes. Stepping through a heavy velvet curtain and into the balconied private seating, Polly faced the next two terrible shocks of the evening.

The box where she’d be watching Toks’ performance was awfully, horribly familiar, and Nikoloz Konstantyn Tokarycz hadn’t changed in sixteen years.

He didn’t recognise her.

He was still charming. As charming as his cousin. The same effortless poise, the same killer cheekbones and devastating good looks. Artis didn’t even have time for a discreet whisper in his ear before Toks swept onto the stage.

She knew where Polly was seated. Shot her a cocky wink and an easy smile before bowing to an audience clearly rapturous to see her. She turned and led the orchestra into a sublime interpretation of the Lili Boulanger piece she’d been studying all week. It was delicate, profound and staggering in its beauty, but the glint of the spotlight on that straw-blonde hair looked just like a splash of sunlight through a bomb-shattered roof, and it was all Polly could do but turn and marvel at the man beside her.

The same green eyes. The same damned hair.

Polly had last seen it down the scope of a rifle.

She wasn’t sure how she made it through the concert, especially after the short pause in proceedings when the crew wheeled a grand piano on stage and Toks led the orchestra through Ravel’s concerto in G from the piano.

Polly still had enough of herself to roll her eyes. What an insufferable show off! The Ravel was famous for its intricate orchestration and demanding piano solos. Pulling off such a challenging feat was exceptional in the extreme, but Toks managed it with aplomb. The performance was dazzling, astounding, and Polly hung her entire being on every note, on the picture of accomplishment in the woman before her.

And then it was over, and they were out in the western foyer again, Artis and Sumi doing their best to keep her away from that awful ruined piano. Toks joined them, ebullient in her triumph, downright fucking gorgeous in her tux. She kissed Polly on the mouth, right in front of everyone, but the maestro’s fawning fans pulled her away all too soon. She was shaking hands and being glorious, and Polly watched her with a half-smile, the world swirling around them both, swirling between them, the current slowly but surely pulling them apart.

Polly slipped away.

Back into the darkness of the empty auditorium.

The piano was still there.

Polly climbed familiar steps to the stage. The silence was deep. The darkness was almost total, just the dim glow of the workers.

Ghostlight.

Very carefully and very deliberately, Polly placed one leg of the piano stool onto the sustain pedal, jamming the strings open.

Then she sat in the first violin’s chair.

And did nothing.

Toks found her there later. Half an hour perhaps? Or a lifetime ago? She came to find her, to save her, just as Polly had always trusted she would. As she hadn’t done before.

Polly’s mind was a mess.

“There you are, darling!” Toks was bouncing.

Her voice woke the piano.

The middle frequencies stirred first.

Polly felt her sanity slip on their hum.

Toks strolled through the auditorium. She was still in her tux, her hands in her pockets. Her bowtie was undone, the white tails hanging around her throat, the top buttons shot. She was everything Polly had missed and needed with all her soul for sixteen years.

Her confident smile almost cut through the turmoil in Polly’s head.

“Sumi said you need to talk to me.” Fuck, she was smug. She swaggered up the steps to the stage, so at home in her environment. “Not completely true. She also said I need to talk to you, but I love it when you need me, baby.”

She was laughing. Her low, sexy tone and the tread of her heels on the polished wood of the floor woke a new set of frequencies. Polly needed her. She needed Toks. But she was falling.

Toks posed before her. Magnificent and victorious. “What did you think? How did you like my Ravel, hmm? I killed it.”

Polly sobbed.

The piano heard her. Echoed her. Began to moan.

Toks finally noticed. She was on her knees in front of her in a moment. “Pearlie? Darling? What’s wrong?”

Her hands, so warm and strong, clasped her face. Her gaze searched for Polly’s. Her jubilance fluttered and crumpled at whatever she saw in Polly’s eyes. Nightmares loomed out of the darkness and superimposed themselves over her face. Polly saw her lips move and heard furious shouting, terrifying orders in a language she didn’t understand. There was the clatter of gunfire, Violet’s ceaseless crying, the smell of blood – and the endless, torturous howl of the piano.

“Polly!” Her hands fell to her shoulders and shook her. Polly didn’t want to frighten her, but she spiralled again, her head lolling back. Someone sobbed, and Polly realised it was her.

“I’m fine,” she said – or she tried to. Instead, an awful cry shook the piano entirely out its slumber and it rang with her pain.

“You’re not fine,” said Toks. “And what the fuck is that noise?!” Exasperation mixed with her confusion and she stood and spun to look at the piano. When she clocked the stool on the sustain pedal, she froze.

In agonising slow motion, Polly saw her salvation, her passion and her ruin collide in the bitter, ugly mess of Toks’ expression.

“You are not fine, Polly Paterson,” Toks whispered. “You can’t possibly be.”

“I’m—”

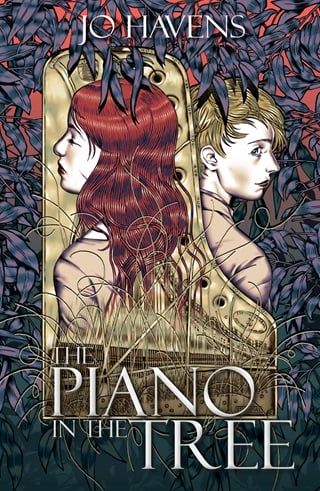

“Don’t you dare say it. What even is this, Polly? Please, help me understand, because I just— I can’t—” She swept one hand up through that sunkissed hair and was impossibly beautiful. “I thought we—” She choked and started again. “You hung my piano in a tree. You have a graveyard of them in your music room at Jerinja. You dump them in rivers, in the rocks by the beach. You fill them with cutlery, for fuck’s sake, and call it art. You dismantle and destroy every fucking piano you touch, but you won’t play one. We always played music together, Polly, but what is this? Please? I don’t understand.”

It was an aria of anguish and the piano resonated with her disappointment. It droned and hummed with her despair.

It thundered with Polly’s failure.

“I can’t do this,” Polly whispered.

“What?” Toks fell to her knees again.

She’d get her perfect suit filthy in the dust, in the blood, Polly thought.

“What do you mean this?” Sheer panic in her tone. Toks waved a hand between them. “Do you mean us? Polly? But the last few weeks have been wonderful, haven’t they? God— haven’t they?” Proud, confident, accomplished women like Toks didn’t whimper, but the piano whimpered back. Her hands gripped Polly’s, piano fingers with a wiry strength, cutting into her skin like zip ties, like knives—

Polly moaned. “I can’t—”

“Please don’t do this, Polly. Whatever this is, we can talk about it— or not, if you don’t want to! Whatever you want, my darling Pearlie. We can just keep going as we have been. Three more concerts here, and then Sydney. We can do that, can’t we? Just please don’t— don’t leave me—” She slapped a hand over her own desperation and her final plea sent a single set of harmonics ringing louder than the rest.

F sharp.

“No!” Polly snapped her teeth shut and snarled at her captors, but she couldn’t take it back.

She saw the word hit Toks in the gut and saw her desperation shatter into bitterness. The shards fell into a well-worn, familiar rut and crystallised into self-preservation. Her eyes lost their love and dulled with surrender.

Polly had been so stupid to think they could have survived this. The men of the Securitate loomed over her. They shouted. They hit her. They cut her. The song of the piano drove her deeper inside her head and she waited, waited, for the silence.

She stared at Toks and couldn’t move.

“No, of course not,” Toks murmured, dry as the dust. The piano heard her resignation. Played it back to them, twice as bitter. It choked them both and Polly gasped for breath. Toks stood up. Brushed the decay and the ruin of their love from her thighs and sneered down at her. “I suppose I should be glad you actually said no to my face this time rather than leaving me standing there, waiting for you. In the snow. In Berlin.”

She was still so proud. Still so beautiful.

A door slammed just behind them at the back of the stage.

It roared like a gunshot.

The piano bellowed.

Polly clapped her hands over her ears and realised she was crying. Tears were wet on her cheeks. She slid slowly off her chair to her knees.

Nikoloz Tokarycz jogged onto the stage and Polly saw the moment he remembered her too.

She was making it easy for him, the last dry part of her mind told her. She was sobbing hopelessly on the floor in front of that piano just like when they’d first met. He’d been a lieutenant colonel in the Securitate then, with the uniform to match.

He gaped at them both, but like the gentleman he’d always been, he reached down a hand to help Polly to her feet.

“Go easy on her, Ksenia.”

Toks growled at the unfairness.

“Honestly cousin, leave her alone.”

“But I have!” Toks cried, and her beautiful face twisted with grief. “I left her alone. She left me alone. I’ve been alone for sixteen years!”

All her pain and all of Polly’s was amplified by the piano and the entire cathedral of music sang with their torment. The sound held Polly in its thrall, as it had all these years. It meant she barely heard Toks when she begged with the last of her hope.

“Please, darling Polly? Please don’t do this to me again.”

There was a long, hopeless moment.

“Come home, Poll,” said a soft voice.

Justin was there.

Polly blinked.

Daz was at his shoulder, and the rest of the UN Peacekeeping soldiers who’d been part of the team come to rescue them. Their blue berets. Their safe, smiling faces. Their bravery and the way they’d died to save them.

Except Polly had been the only one left.

She screwed up her eyes and looked again.

It was only Justin.

He glared at Nikoloz and Toks. “Idiots,” he muttered, and kicked the piano stool off the sustain pedal. The dampers fell to the strings with a thud and there was silence.

Just Toks’ breathing, and Polly’s heartbeat loud in her ears.

“Come home, Poll.” Justin held out his arm.

Polly waited for Toks to do the same.

She didn’t.

Justin wrapped his arm over Polly’s shoulders and held her until she stopped shaking. He took her safely home. All the way to Jerinja.

Fullepub

Fullepub