Chapter 2

When I open my eyes each morning, I search for the silver alarm clock I used to keep on my nightstand. It looked like one half of a tin can, with a yellow-tinted dial encircled with Roman numerals.

For years, the repetitious ticking would keep me up at night. My heart would race, and I would hold my pillow over my head until the sound was silent, and I could finally fall asleep. It wouldn’t be until morning that I would hear the tick, tick, tick, just before the hollow bell pierced through my head. I would slap my hand over it, usually knocking it onto its side. Mama and Papa both had early work duties and I was responsible for making sure my little sister, Olivia, and I made it to the schoolyard on time.

The responsibility at a young age wore on me, or at least I thought it had worn me down, but I didn’t know better then.

Now, I must rely on my internal clock to wake up each morning. I would give up my last few belongings just to hear the ticking of that old timepiece again. No one warned me there would eventually be a last tick.

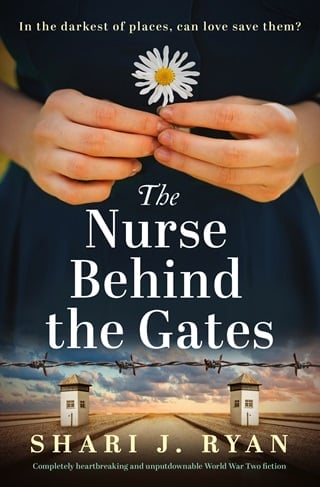

We’ve been living in the ghetto of Warsaw for just over a year since we were forced to leave our home in Krakow. We were told Jewish people were being relocated to a community specifically for our kind. When Germany invaded our country, we had no say over what we were entitled to after Mama and Papa had devoted their existence to giving Olivia and me a life many would do anything to have. Neither status nor stream of income makes a difference to the Germans. A Jew is a Jew, and nothing can change that. Their promises of safety and shelter were lies. We live like sewer rats, hoping the food we procure keeps us alive—praying Papa can continue to supply extras for us with his diminishing connections on the outside of the walls. The sewers have become our only means of passing items from one side of the city to the other, and the Germans are now aware of our activity. We aren’t allowed out of the ghetto—the space enclosed by a wall, one twice the height of any person, and topped with barbed wire, closed off to a city square made up of a dozen blocks in each direction. Our habitat is the definition of a prison. We are Germany’s prisoners.

Mama is already awake, crouching over Olivia, who is still sound asleep among the warmth of the clothing-filled pillowcases we use as mattresses. When she was a little girl, she would wake up if one of us blinked too loudly, but these days, she can sleep through a shrilling air-raid siren. I’m sometimes envious of this twelve-year-old girl.

“Lu-lu, it’s time to get up, darling,” Mama whispers in Olivia’s ear while brushing away the sweat-ridden curls draped over her forehead. It hasn’t been warm down here in longer than I can remember, but the air is stale and thick, and it seems to settle between the four brick walls we occupy.

Olivia rolls onto her back and blinks to see through the darkness. “Where is Papa?” she asks as she does every morning, hoping for a different answer than the one Mama replies with.

“He got an early start. There was a meeting of some sort.” There’s always a meeting, but he’s secretive about them.

“A meeting for what?” I question, rolling up the flattened pillowcases I slept on.

Mama glances over her shoulder toward me. I can only see the glisten within her eyes. “A meeting,” she repeats. I wonder if she knows who he meets with or if she’s wondering like we are. I’m not sure she’d say either way.

Papa refuses to give up or accept being trapped between the stone walls that imprison us within the beautiful city we had always loved. Warsaw is no longer a community filled with cheerful residents; it’s a holding cell for Jewish people. Whoever he meets with must feel the same, but I’m not sure what can be done about our situation: we’re too few against the German forces.

I don’t blame Papa—in fact, I wish I could go with him. Mama needs me more, though. Therefore, I don’t fuss over what I do throughout the day.

While I pull up my pair of slacks and button my shirt, Mama helps Olivia with her dress—one she used to love, but now despises because the colors are no longer bright, and the hem has begun to fray.

“Papa was able to obtain enough eggs and potatoes yesterday to feed a good amount of people today, but we have a lot of work to do,” Mama says, running her fingers across the sides of her hair that she has pinned up. “Isaac, I need you to peel the potatoes, and, Olivia, I’ll need you to help me keep the fire burning.”

Though we have next to nothing, we have more than many others do and, for that reason, we help whoever we can with what Papa is able to exchange in the underground market.

I pull the loose bricks out from the accessible hole in the wall, one by one, until there are eight full-size bricks stacked on the dirt-covered ground. Olivia squirms through the wall first, then Mama. I hand her the bricks, one at a time, and wriggle through into the short corridor that leads to an above-ground exit. It only takes me a couple of minutes to replace the bricks before we’re scaling up a sewer line ladder that will bring us to the storage space of an old ice-cream shop.

I’m first up the metal rungs so I can move the grate above our heads. I pull Olivia up and place her down on her feet, and help Mama up, then replace the sewer plate.

“The potatoes are up in the back-left ceiling panel,” she tells me. We have a distinct ceiling panel for each variety of food we manage to bring in, and then there is a large metal can hidden in the corner behind the old broken freezer. Mama uses it to keep foods as cool as possible before cooking them.

Olivia makes her way to the storefront windows to peek outside. I sometimes wonder if she’s hoping to find a different scene. At twelve, I suppose she’s still full of hope—another reason to be envious of her.

“It’s raining, but there’s a line of people outside,” she reports.

A line of people once meant men and women standing shoulder to shoulder or front to back in orderly fashion. It has a different meaning now. The hungry Jewish people outside don’t have the energy to stand for long, and they often huddle together against a wall for comfort while they wait for a scrap of food. There was no way to know who would be in the lower class or higher class of a ghetto, but some had everything taken away from them, and others found means of holding onto the little they had left. No matter what anyone has or doesn’t have here, everyone is hungry, cold, filthy, and miserable. Some are just more so than others.

The three of us move as quickly as we can to prepare the extra rations. By seven each morning, we open the front door just enough to allow in a slight breeze along with the first few people waiting for mercy.

It’s been about seven months since the stone walls went up, and in that time, people have lost everything, including most of their body weight. Some aren’t fortunate enough to have shelter and sleep on the sidewalks. Roads are filled with ravenous bodies morphing into skeletal figures. The small bit of extras we distribute still aren’t enough to keep people alive.

Two women and a young boy standing before us are holding onto each other for support. Their eyes are bulging from the lack of fat in their flesh, and their cheeks are sunken, drawing a precise line around their jawbones. The boy must be around Olivia’s age, and it takes everything I have not to scoop him up and offer him some of the life I somehow still seem to have inside of me. We are all suffering, but the children—they don’t understand. They shouldn’t be able to comprehend the true meaning of hatred at such a young age, but within these walls, there are orphans who not only lost their parents, but watched them starve to death as they fed every morsel of food to their little mouths.

There’s no end in sight, just dilapidated bodies waiting for their last breath, the scents of body odor and rotting flesh, and the sounds of cries that carry on from dusk to dawn. I suppose starvation might be a better solution than fighting for survival. It seems clear, the Germans don’t intend to let us out of here alive.

For the next couple of hours, fellow Jewish men, women, and children continue to trickle into the muggy shop until there is no food left to serve. The worst part of every day is when we must turn away those who had been waiting with hope that there’s something left.

When I see their pleading eyes and their empty faces, my heart feels like a lead boulder bearing heavily on my ribcage. It’s hard to push through the weakness to clean up just so we can make it look like we were never here. These moments steal my desire to push forward, and it seems when I’m at my lowest, something surges in me to take on this battle.

Then I hear it, a scream—not one from bodily pain, but from a shattered soul. I can’t stop myself from moving toward the cries, wondering if I can help whoever it is. With a few steps out on the street, I watch as a man falls to his knees in grief before a woman I assume to be his wife. Her frail hands shake as she covers her open mouth. “My baby,” she cries. “Why?” The woman’s knees give out and she falls to the ground too. The couple fall into each other, crying so hard, the veins pulsate across their foreheads.

All I can do is stare and assume their child died from starvation, sickness, or was shot while trying to find food in the underground tunnels like many children are sent to do.

When I come to my senses and realize I’m gawking with no right to witness their intimate pain, I turn back, catching a glimpse at the watchmaker shop toward the end of the block. The sign dangles by one hinge instead of two, highlighting the varying degrees of damage throughout this city. With a quick look, the image of a timepiece on the waving banner looks real, but the minute and hour hands never move. It’s the worst kind of reminder that my life may stand forever still.

* * *

Fullepub

Fullepub