Chapter Twenty

Twenty

Teddy had lied to Stella. He wasn’t waiting along the rail at five o’clock in the afternoon on the second day of spring, watching the fashionable equestrian throng trot by. It would have been impossible to do so.

For one thing, he’d underestimated the difficulty in getting there in his chair. The ground was still saturated from yesterday morning’s rain, with patches of ankle-deep mud that would have played havoc with his wheels. For another, the crowds were such that navigating through them would have taken more time and effort than he had to spare.

Instead, he’d arrived in his new wagonette, with both his wheeled chair and Jennings disposed in the back of the vehicle, at the ready should Teddy require them.

He gripped the reins hard as he entered the South Carriage Drive of Rotten Row, ably steering the placid Samuel through the growing traffic. He was no amateur when it came to handling the ribbons. It nevertheless took the whole of his attention. He was acutely conscious of his limitations—the fact that all of his control derived from the strength of his upper body. He was equally conscious of the obtrusiveness of his chair, strapped down in the back of the wagonette. It was a glaring announcement of Teddy’s condition to everyone he passed.

He wasn’t ashamed of it—neither his chair nor his disability. But the fact that he must give over his sense of privacy in his own body never failed to rub him on the raw. His health was no one’s business but his own. And yet, the presence of his chair made it everyone’s business. Strangers felt at complete liberty to gawk at him. Or worse. Over the past several years, some had the audacity to interrogate him about his condition or to offer their unsolicited advice.

“ Have you tried an electricity machine? ” a matron lady had once asked him at a shop. “ It did my invalid mother’s withered leg a world of good .”

“ See Dr. Fairbank in Blackheath ,” a gentleman stranger had recommended. “ He’ll have you out of that chair in no time .”

“ Simple exercises, performed daily, are the thing ,” another man had declared when encountering Teddy at a gallery. “ Have you ever tried stretching? ”

As though Teddy hadn’t been to every doctor and performed every exercise. Had he ever tried stretching? Had he, hell.

Regrettably, there was no avoiding the stares and the remarks. Not unless Teddy became a complete recluse. And that wasn’t an option anymore. Not now he had his artistic future to contemplate and his muse to secure.

But nearly twenty minutes later, there was still no sign of Stella Hobhouse and her famous gray mare.

A leaden weight settled in Teddy’s gut. She’d told him, in her last letter, that she hadn’t yet persuaded her brother to bring her to town. He’d nonetheless expected her to be here. Lady Anne had been married yesterday. Teddy had seen mention of it in the papers this morning.

Had Stella missed the ceremony? Was she, even now, in Fostonbury, still practicing being small and quiet?

He brought Samuel around a bend. The gelding jogged gamely forward as Teddy scanned the crush of riders for any sign of his muse. He’d almost given up hope when he saw her.

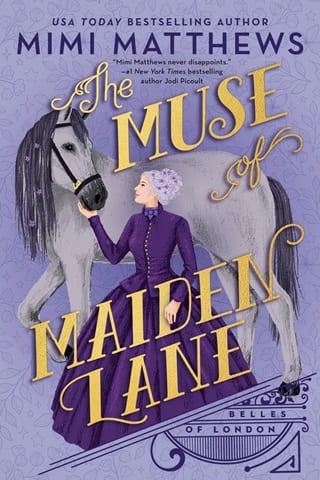

Stella emerged from the crowd, trotting forward on a striking, pale gray mare. The horse’s coat shimmered like silvery vapor in the sunlight. So, too, had Stella’s hair shimmered in the parlor at Sutton Park as Teddy had sketched her, shining pearly bright in the cold winter light that had poured through the windows.

But Stella’s hair color wasn’t visible now. Her tresses were covered in a close-woven net and topped by a jaunty plum riding hat. Her habit was made in a similar hue—that deep shade of purple that appeared almost magical when fitted to her figure. Its skirts draped gracefully over her legs, rippling provocatively against her mount’s side as Stella picked up speed.

Teddy saw her before she saw him. She was gazing out toward the rail as she breezed by, looking for him, perhaps, or for someone else of interest. Her groom followed close behind on a stocky chestnut gelding.

She’d almost passed Teddy when he finally brought himself to speak.

“I thought you’d be galloping for certain,” he said loud enough for her to hear over the drumbeat of hooves.

Her head jerked in his direction. A smile spread over her face. “Mr. Hayes!” She slowed her mare. “I didn’t know you’d be driving.”

“Nor did I.” Teddy shortened his reins, easing Samuel out of the way of traffic, as Stella turned her horse to ride up alongside his wagonette. “I only bought it a few days ago. What do you think?”

“It’s very smart.” She glanced at the back, taking in the presence of both Jennings and Teddy’s wheeled chair. “Practical, too, I see.”

“Naturally,” he said. “I’m the soul of practicality.”

Her eyes twinkled with laughter.

His mouth pulled into a foolish grin in return. By God, but it was good to see her again.

During their months apart, he’d begun to wonder if he’d imagined how beautiful she was—how very perfect she was for his painting. But he hadn’t imagined anything, had he? Indeed, it was possible that his memory had blunted the effect of her.

He felt that effect now at full force. It seemed to be magnified on her mare—the two silver figures amplifying each other with the brilliance of twin stars.

“Your mare is excessively energetic,” he said.

“You should have seen her this morning, when I was galloping with Mrs. Malik and Mrs. Blunt. Locket had far more energy then. Now, she’s actually quite manageable.”

Teddy arched a brow at the mare’s dancing legs and trembling nostrils. If this was manageable, he couldn’t imagine what the horse was like when she was un manageable. “I thought she would be darker for some reason,” he remarked.

“She was when she was a filly.” Stella patted her mare’s shoulder with a slim, gloved hand. “Gray horses fade as they get older, but her mane is still silver and she has dappling on her legs, as you see.”

“She’s nearly white everywhere else.”

“A white horse. How appropriate.” She let the mare prance alongside the wagonette for a few steps as they drifted further from afternoon traffic. “My friends and I have often been called the Four Horsewomen. Either that or the Furies.”

“There were only three Furies.”

“We were three to begin with. Then, when Mrs. Malik arrived last season, we were four. Now, regrettably, there’s only one of us left. Just me, a gray lady on my white horse. An ominous figure, I daresay, if one countenances the biblical symbolism.”

“I’m no Pre-Raphaelite,” Teddy said. “Biblical symbolism is lost on me.” He drove on alongside her in the direction of the Serpentine. “I can tell you, however, that in terms of light, you and your mare are magnificent.”

Stella briefly turned her head away from him, embarrassed by the compliment. “In terms of light,” she repeated as though examining the phrase. “What manner of light? Is it the sun? The shadow?”

He caught her eyes. “Starlight, of course,” he said solemnly. “For you, it will always be starlight.”

Her cheeks took on a faint hint of color. “You’re incorrigible. I haven’t even asked how you are yet, and you’re already plying me with your beastly artistic compliments.”

They weren’t purely artistic anymore. Not after that kiss. Teddy wasn’t too proud to acknowledge it, even if it was only to himself.

“You can still ask me,” he said. “If you must insist on preserving the proprieties.”

“How was your journey from Devonshire?” she inquired.

Teddy’s smile broadened at her air of formality. “Long,” he replied frankly. “The Finchleys accompanied us. We’re staying with them in Half Moon Street for the remainder of the month.”

“And your other friends? Did you leave them in good health?”

“They were hale and hearty enough when we departed Devon. The only person suffering any ill effects is my sister. Though it’s to be expected, given her condition. She and my brother-in-law have lately learned that they are to be parents.”

“Oh!” Stella’s eyes lit. “What happy news! You shall be an uncle.”

“Indeed.”

“You don’t sound very enthused. Don’t you like babies?”

“They’re very loud, in my experience. And perpetually sticky, with I don’t know what. Other than that—”

Her mouth quirked with amusement. “Spoken like a confirmed bachelor.”

“But true, nonetheless,” he said.

They continued over the rolling green that led away from Rotten Row. Hyde Park was a vast expanse, with more in common with a rambling country woodland than an isolated patch of grass in a bustling city. The further they drifted from the daily promenade, the fewer horses and carriages there were to distract them.

Stella allowed her mare to stretch into an extended walk. If she’d given a cue, Teddy hadn’t seen it. He at once comprehended why.

She had extraordinarily quiet hands, and an equally quiet seat. It was all of a piece with the mask she often wore. That beguiling expression of tender gravity that had left him riveted the first time he’d set eyes on her. It was beguiling precisely because of the fathomless depths beneath.

Indeed, she appeared to ride as she lived. Under her luminous stillness, she was subtly at work, managing her high-spirited mare with invisible aids—slight shifts in her weight, unseen pressure from her leg, and delicate crooks of her fingers.

“Is Mrs. Archer very ill?” she asked.

“A minor indisposition,” Teddy said. “It’s not uncommon in her condition, but it makes crossing the Channel at the end of the month an uneasy prospect for her. She isn’t much looking forward to it.”

“Sea sickness, of course. It must be doubly trying if one is expecting a baby.”

“Undoubtedly,” he said. “Though, Laura claims that the happiness of her condition outweighs any discomfort.”

“I’m sure it does,” Stella said. “She and Mr. Archer must be overjoyed. Please convey my best wishes to them.”

“I shall.” Teddy again caught her gaze. He hadn’t come to the park today to talk about his sister and brother-in-law. “Enough about my family,” he said. “How are you ? That’s more to the point.”

“I’m very well. I am here, as you see.”

“I never doubted you would be. But how did you manage your escape from Elba? I trust you didn’t travel alone, as you threatened to do.”

“I would have done,” she said. “I’d even purchased a rail ticket to London, to my brother’s dismay. But before I could use it, the imperial guard arrived to rescue me.”

“The imperial guard?” He laughed.

“In the form of my friend Mrs. Blunt. She and her husband, Captain Blunt, came to Fostonbury to fetch me. It was on their way from Yorkshire, so not too much of an imposition, I endeavor to hope.”

“Mrs. Blunt is one of the Four Horsewomen, I take it.”

Stella nodded, another smile springing to her lips. “I’m staying with her and her husband at Brown’s Hotel until the end of the month. They’re only remaining in London a fortnight, and then they shall return to Yorkshire.”

“I see I must act quickly then.”

“What to do?” she asked.

“To lure you to my new studio,” he said.

Stella’s cheeks flushed with color again. She cast another guarded glance at Jennings.

In his eagerness to speak with his muse, Teddy had temporarily forgotten that his manservant was but a few feet away, witnessing every look and every word. The abrupt reminder caused his chest to tighten on an unexpected surge of bitterness.

It wasn’t uncommon for a fellow to drive out with a groom or tiger in attendance. Were Jennings one of their number, his presence would be ignored. But Jennings was no ordinary servant. His function was more personal and therefore more intrusive.

So, too, might an elderly invalid travel with their nurse—an attendant empowered to convey them here or there, and to tend to them when their condition became too onerous to manage alone.

Teddy had long ago resolved not to be self-conscious about the fact that he needed such care. As Alex had said when he’d first hired the man, Jennings’s presence was the very opposite of a burden. He was there to help Teddy gain a measure of independence.

But this was different.

For the first time in a very long while, Teddy yearned to be, once again, that athletic young man who had strode through Talbot’s Wood five years ago in search of inspiration for his paintings. A man who could meet a young lady on terms of equality, unencumbered by attendants and appliances.

Stella resumed looking straight ahead as she rode. Her own groom followed several lengths behind, too far away to hinder them. “You’ve secured a studio?” she asked in a tone of polite but disinterested inquiry.

Teddy tried not to take it to heart. He told himself that she was merely conscious of Jennings and, therefore, anxious to preserve the proprieties.

At least, Teddy hoped that’s all it was.

Serpentine Bridge lay ahead, and with it a smattering of riders and drivers who had, like them, drifted away from the Row. The moment was no longer suited for private conversation. Not when Stella was riding, and he was driving.

“I’d like to show it to you,” he said. “If you’d be willing.”

She hesitated before answering. “When?”

“May I call on you Monday afternoon at Brown’s? We could drive out to see it, if you’re not otherwise engaged. It’s only but two or three miles from here.”

Another lengthy pause. And then: “I am not engaged,” she said, softly meeting his eyes.

Teddy’s pulse gave an unsteady leap. “Splendid.”

He could talk to her at the studio. There, they could be alone, just the two of them, while Jennings remained on the street with the wagonette. She would be leaving London in less than a fortnight. It would be Teddy’s last and best chance to convince Stella to pose for him before she returned to Derbyshire. He was resolved to do whatever it took.

“Monday, then,” he said. “You may expect me at two o’clock.”

Fullepub

Fullepub