Chapter Fifteen

Fifteen

Derbyshire, England

January 1863

The day of Miss Trent’s visit arrived with unsettling swiftness. Stella spent the morning just as she’d spent every morning and afternoon since returning from Hampshire—on Locket, galloping through the woods that abutted the vicarage. Riding had been Stella’s only respite from the endless chores she’d been tasked with in preparation for their guests.

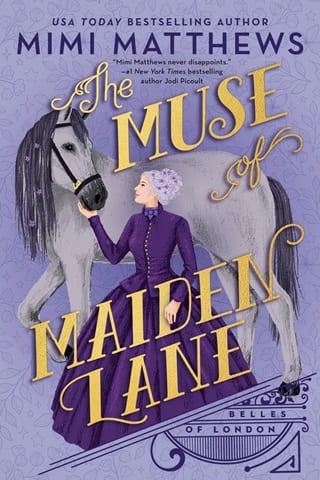

A fresh snowfall covered the ground. Locket’s hooves flew over it with ease as she and Stella charged along their favorite route—a meandering trail that ran through a stand of silver birch trees, alongside a frozen stream, and then up a hill to join with the main road to the village.

Locket loved the familiarity of the flats and the challenge of the ascents. She was a creature who gained confidence through the terrain. The firmer the footing, the greater the length of her stride.

Stella leaned forward over Locket’s silvery neck as the mare surged beneath her through the snow, the earthly incarnation of a star streaking across the sky. Icy wind tore at the net veil of Stella’s high-crowned riding hat and whipped at the heavy skirts of her habit, sending them flapping behind her in a stream of mazarine-dyed wool.

A coach rolling down the road in the direction of the vicarage slowed as she and Locket flew by. Stella paid it no mind. She wasn’t thinking of scandal or spectacle. She was only thinking of speed.

Anne had once said that if given her head, Locket could bolt all the way to Bridgehampton. Stella wished it were true. Wished she could loosen the reins and let Locket carry her far away from Fostonbury, all the way to London.

Or to Devon.

Not for the first time, her thoughts turned toward Teddy in his cliffside estate. To that scorching kiss they’d shared in the sleigh. Who knew when Stella would see him again? Or if she would see him again.

Daniel was still set against accompanying her to Anne’s wedding. Never mind that Stella had exerted a herculean effort to soften his resolve. She’d spent the past two weeks diligently copying and organizing his notes, accompanying him on parish visits to the sick and elderly, and overseeing a thorough cleaning of the vicarage. She’d made the box room fit for occupancy, inventoried the linens, and prepared a month’s worth of menus. She’d even penned an invitation to Squire Smalljoy in her own hand, personally inviting him to join them at tonight’s dinner to welcome Miss Trent and her mother.

All to no avail.

Daniel was no more inclined to take Stella to London than he’d been on the first night she’d asked him.

Stella said as much in the letters she wrote to Julia and Evie. But not to Anne. Stella told her nothing of the troubles she was presently enduring. The last thing she wanted was Anne making good on her threat to come and collect Stella personally. And Anne would, too.

It wouldn’t do. Stella would simply have to find another way to get to London this spring.

Turning Locket back toward the vicarage, Stella trotted the mare, then walked her to cool her out. By the time they reached the rear entrance of the stable, Locket was calm and steady, and ready for a bucket of mash.

“She’ll be quiet until this afternoon, I reckon,” Turvey said, taking Locket’s reins as Stella dismounted. “Doesn’t take her but a few hours to get restless again.”

“She and I both,” Stella murmured. She gave her mare an affectionate scratch on the neck. “We’re of a similar temperament, aren’t we?”

Turvey respectfully refrained from answering as he led Locket away to untack her.

Stella walked back to the vicarage, shaking the gray horsehair from the skirts of her habit as she went. There was still much to be done before this afternoon. Miss Trent and her mother were due to arrive at Fairhook Station at half past two. Daniel would be going to fetch them in a hired gig.

But as Stella crossed the grounds to the front of the house, she saw—much to her alarm—the same coach she’d passed on the road now parked in front of the vicarage door. Two petite ladies in sturdy cloaks and bonnets had descended from the vehicle, one young and one old.

It was Amanda Trent and her mother.

The portly, brassy-haired Mrs. Trent was overseeing the removal of a number of trunks and leather traveling cases from the coach, with Daniel’s help. Mrs. Waltham stood at the open door of the vicarage, looking rather harried, as she showed the footmen where to put them.

Stella briefly considered slipping away to her room to hurriedly wash and change, but it was too late. Miss Trent had already spotted her.

“Miss Hobhouse!” Miss Trent exclaimed. “I thought it was you we saw on the road.” She swept across the drive to meet Stella. Not much more than five feet in height, she possessed all the steely purpose of a conqueror come to finalize her battle plans—an effect completely unmarred by her flaxen ringlets and her tiny pink rosebud of a mouth.

“I told your brother that you would be back directly,” she said, “as wild a pace as you were keeping.”

“Miss Trent.” Stella exchanged curtsies with the young woman. “This is a surprise. We weren’t expecting you to arrive until this afternoon.”

“You must call me Amanda,” Miss Trent insisted. “And I shall address you as Stella. We shall be family soon, shan’t we?”

“Yes. It seems we shall.”

“The very reason I suggested we take an earlier train. Why delay the start of our lives together? I assured Mama that you and dear Mr. Hobhouse wouldn’t mind. ‘Miss Hobhouse will have all in readiness,’ I told her. ‘She is an excellent housekeeper to her brother. Unmarried sisters always are.’?”

Stella pasted on a smile, ignoring Amanda’s barbs. This is how it always began with her. The subtly cutting comments and treacle-covered darts. Amanda Trent was an underhanded opponent. It was impossible to war with her openly, but it was war all the same, and they both knew it.

“You are welcome at any hour, of course.” Stella gestured to the front door, conscious of her soiled riding habit and the wild strands of her gray hair sticking to her perspiration-damp brow.

No doubt she looked a fright, especially to someone as notoriously fastidious as Amanda. The young lady had just traveled all the way from London, but still appeared as fresh as a nosegay.

Daniel shot a severe glance in Stella’s direction as she passed. He’d warned her not to embarrass him in front of their guests, and here she was, offending everyone’s sensibilities in the very first moment.

“I beg you would excuse my sister’s unfortunate appearance,” he said. “Stella? Hadn’t you better change before joining us in the parlor?”

“Indeed,” Stella replied. As if she hadn’t been intending to do that very thing!

“It appeared an exciting ride.” Amanda linked her arm with Stella’s as they walked to the door, affecting an intimacy the two of them didn’t share. “Though, if you’ll permit a word of advice, not perhaps an excessively wise one. A lady should never gallop her horse. Mama was quite shocked to see you doing so. She mentioned it to your brother straightaway.”

Stella’s spine went rigid at the reprimand. It was one thing for Amanda to meddle in every other aspect of Stella’s life, but to dare to interfere with her riding?

“I don’t believe in absolutes,” Stella said with a creditable degree of composure. “Words like always and never leave no room for extenuating circumstances.”

“Are there any such circumstances when it comes to riding so recklessly?”

Stella could think of half a dozen or more. But there were only two that applied to her wild rides on Locket. “My horse requires a good gallop to keep her civil,” she said. “As do I.”

“ Requires ,” Amanda repeated with a titter of indulgent amusement. “Such an interesting choice of words. One requires so little in life, really. And do consider, if you would but exercise self-restraint in your habits, you would find yourself amply rewarded by your brother’s esteem. Pray, let me be your example.”

“You are too kind,” Stella said tightly.

“I might offer guidance in other respects as well,” Amanda continued. “Your brother tells me that you’re eager to engage a drawing master?”

“I’ve made inquiries, yes,” Stella admitted. She hadn’t had much luck in her search. All the gentlemen drawing masters recommended to her had either been too far away, or too expensive.

“A costly indulgence,” Amanda said. “And an unnecessary one now I am here. My watercolors have often been praised in Exeter. I shall be pleased to offer you the benefit of my humble expertise.”

“How generous of you,” Stella said.

Behind them, Amanda’s mother entered the hall on Daniel’s arm. She acknowledged Stella’s presence with a cool nod. Mrs. Trent rarely paid Stella any attention, unless she was making herself infamous in some way. The remainder of the time Mrs. Trent treated her future son-in-law’s sister as someone possessing no more importance than an unattractive piece of furniture in an otherwise pleasant room. A shabby chair or a garish ottoman, jarring in its appearance, but easily dispensed with at the first opportunity.

“Careful with that!” she snapped at the footman who was trailing behind them, struggling with the larger of her trunks. “It contains more than your position is worth!”

“Beg pardon, ma’am.” The footman readjusted the heavy trunk on his shoulder.

“Good servants are impossible to come by,” Mrs. Trent said to Daniel. “It stems from laziness. A great affliction among the poor, and one of the chief reasons for their sad state. You’ve referenced it yourself in your scholarly writings.”

“Quite true, madam,” he said. “Laziness is a terrible vice.”

Stella shot a look of apology to both the footman and Mrs. Waltham, the latter of whom had received Mrs. Trent’s words with an expression of barely concealed outrage. “Laziness isn’t at issue among the people of Fostonbury,” Stella said. “We’re all hard workers hereabouts. Isn’t that so, Mrs. Waltham?”

“Yes, miss,” the housekeeper answered with offended dignity.

“Would you be so good as to bring the tea tray in?” Stella asked her. “Miss Trent and her mother will be in need of refreshment after their journey.” Extricating herself from Amanda’s steely grasp, Stella moved to ascend the stairs. “Please allow my brother to entertain you while I change out of my riding things. I shall be back promptly.”

?The remainder of the day devolved at a rapid rate. By the time Squire Smalljoy arrived for dinner, Stella’s nerves were rubbed raw, and Daniel, who had already been growing weary of her at the best of times, had since—under the barrage of helpful criticism from Amanda and her mother—begun to look on Stella as the greatest burden of his life.

Add to that the old-fashioned masculine condescension that the squire spewed forth with every breath, and the evening possessed all the necessary ingredients for absolute disaster.

Stella had only to hold her tongue until the final course was served to avert catastrophe. It shouldn’t have been difficult. Neither Daniel, Squire Smalljoy, nor the Trents required conversation from her. She had only to answer yes or no, to smile dumbly, and to bob her head in agreement with every insipid remark.

Naturally, she did none of those things.

“You can’t honestly consider Lord Palmerston to be a moral authority,” she said in response to a comment the squire had made about the prime minister. “The reports of his sordid affairs are too many to number. I’ve heard that some in Westminster have taken to calling him Lord Cupid.”

Her words were met by four shocked faces at the round, lace-covered mahogany table.

Squire Smalljoy was the first to break the appalled silence. “A politician’s personal indiscretions don’t matter a jot when his policies are in good order,” he said as he chewed an oversized bite of fatty mutton. He was a hearty man with a hearty appetite, in every respect. White-haired and full-whiskered, he ate and drank with gusto, rode hard to the hounds, and—at eight-and-fifty—had already sired a passel of children.

The clinking of cutlery resumed as the guests continued their meal. Mrs. Waltham had laid the table with care this evening, putting out their finest silver and the set of blue-and-white china bowls and plates that had belonged to Stella’s parents. Coupled with the lace tablecloth, sparkling glass goblets, and extra branches of costly beeswax candles, the effect was one of genteel elegance.

“His policies are no better,” Stella said. “Had Lord Palmerston not authorized soldiers to invade Peking three years ago, the Summer Palace would still be standing. Instead, it was burned to the ground. And what about his views on women’s suffrage?”

Mrs. Trent coughed loudly into her white linen napkin. Seated at Daniel’s left, she was clad in a plain dinner dress with an untrimmed matron’s cap over her hair. Amanda sat on Daniel’s right, garbed in a similarly modest fashion. She gave Daniel a speaking look.

Obedient to the unspoken plea from his betrothed, Daniel leveled a warning glare at his sister.

Stella ignored it. The only way to extinguish the squire’s interest in her was to illustrate how ill-suited they were. And she could hardly do that while remaining silent. “Palmerston says that it’s enough for fathers, husbands, and brothers to have the vote,” she continued, undeterred. “He claims they’ll act for the benefit of the ladies in their care. What he fails to consider—”

“You do have opinions, missy,” the squire interrupted. “I blame you, Hobhouse. Shouldn’t let females develop such notions.”

“I’ve tried to educate her,” Daniel said apologetically.

“There’s your error.” The squire washed down his mutton with another mouthful of wine. “Education is wasted on the female brain.”

“Rubbish,” Stella said under her breath as she cut into her boiled potato.

Daniel flashed her another stern look across the table. Mrs. Trent and her daughter marked it, just as they’d marked all the others. It seemed to Stella that they exchanged a smug glance every time Daniel sent a scolding frown Stella’s way.

But though the Trents triumphed in her brother’s worsening opinion of her, they had no interest in seeing Stella brought low in Squire Smalljoy’s eyes. It was to both their benefit that the man think well of her. Once Stella was married, she would be out of her brother’s house and permanently out of Amanda’s way.

“I would agree with you, squire,” Mrs. Trent said, daintily dabbing at her mouth with her napkin, “if your reference is to those subjects better suited to young men. But I can’t believe you object to a young lady being schooled in the feminine arts.”

“Not to those subjects, no,” Squire Smalljoy said. “Singing, sewing, a bit of the piano, and a dabbling in French. Whatever course of study improves the prettiness of a girl and makes her a charming companion for her husband has my full endorsement.”

“My daughter is well versed in all of those subjects,” Mrs. Trent informed him proudly. “Along with a thorough course of spiritual education, which I’ve undertaken myself.”

Daniel looked at Amanda with glowing approval. “Miss Trent is a testament to your wisdom, ma’am.”

Amanda bowed her blonde head in meek acceptance of his praise. Her fair cheeks turned a delicate shade of pink.

Stella wondered if some ladies found it possible to blush on command. A useful talent, unquestionably, if one was trying to impress a pious country vicar with one’s modesty and virtue.

“I have done my best, sir,” Mrs. Trent said. “As have you, Mr. Hobhouse, in the absence of your dear departed parents. You are to be commended for your efforts. Miss Hobhouse will make some fortunate fellow a conformable wife.”

Stella choked on her potato. She reached for her wine, hastily draining the glass.

Daniel glared at her. “I did stress the importance of adherence to a traditional course of study to my sister’s governesses. But Stella has a mind of her own. She reads widely, and forms her own opinions.”

“You must guide those opinions, Hobhouse,” the squire said. “As must every man who has the responsibility of ladies under his care. No need for a woman to be troubling her head with politics or philosophy. Ladies should be small and quiet. It’s ever been thus in a happy home.”

“Perhaps in the past,” Stella said. She ignored her brother’s attempts to catch her eyes. “Modern minds take a different view. They understand that women are capable of making valuable contributions, both to scholarship and to conversation. Why, consider the Queen—”

“Small and quiet,” Squire Smalljoy interrupted, addressing Daniel, not Stella. “That’s a woman’s place. My daughters learned it in the nursery. Best to focus on being good little wives and mothers. On cheering a fellow’s spirits, not deadening his eardrums with all this newfangled nonsense.”

“Ah, motherhood.” Mrs. Trent beamed like a saint in a Renaissance painting. “The most sacred of institutions. A lady cannot wish for a more exalted state. Is that not right, squire?”

“Quite so,” he grumbled. “Quite so. A fine daughter you’ve raised there, too, madam.”

Amanda smiled, but said not a word. She didn’t talk overmuch in company. The bulk of her speech was saved for private asides. That was where her power lay: in pitting brothers against sisters and mothers against future in-laws.

“Motherhood is a role Miss Hobhouse is eminently suited for,” Mrs. Trent said. “Do you not agree, Mr. Hobhouse?”

“Oh yes,” Daniel concurred. “My sister is very fond of children.”

Stella refilled her wineglass. Her rising temper had been under questionable control all evening, but now, in the face of these blatantly obvious ploys to see her married off to a man she didn’t like, it threatened to bubble over completely. “On the contrary,” she said. “I find the company of children rather trying.”

It wasn’t true, of course. Stella was fond of children. Indeed, she’d always imagined she would have a family of her own someday. But to admit such a thing in the hearing of a gentleman like Squire Smalljoy would be tantamount to waving a white flag of surrender.

Too late, she realized that all she’d done instead was wave a red flag in front of a bull.

“What’s this?” The squire turned to her at last. “Don’t care for children?”

“It’s not uncommon,” Stella said.

“It’s unnatural, is what it is. Hobhouse! Did you know of this?”

Daniel gave a hollow laugh. “My sister’s poor idea of a jest. Pay it no mind.”

“A dashed poor jest,” Squire Smalljoy muttered as he resumed eating. “The finest quality in a female, mothering and bearing children. My late wife was a saint. Gave her life to my sons and daughters. Lost her life in the end, bearing my youngest. A noble sacrifice, I say.”

“The noblest,” Daniel said. “Very well put.”

The views expressed weren’t any different from those Stella had heard articulated hundreds of times, both by her brother and by the antiquated scholars in his old-fashioned set. She was weary of listening to them.

“Yes, well”—she raised her glass to her lips—“I’m not eager to sacrifice my life just yet. Not for children or anyone. There are things I still wish to do for myself.”

The squire’s brows snapped together. “ Things ? What things?”

“I don’t know yet,” she admitted. “But I do know that motherhood isn’t conducive to riding, and I won’t submit to anything—or any one —that prevents me from galloping my mare.”

Amanda’s eyes found Stella’s in the guttering light of the beeswax candles. Anger glimmered in her face. “My advice was kindly meant.”

“She prefers riding to motherhood?” Squire Smalljoy questioned Stella’s brother. “What manner of girl—”

“Another jest,” Daniel said with a weak laugh. “My sister is aware you’re fond of horses. She’s teasing you on the subject.”

Mrs. Trent tittered. “What a sense of humor our Miss Hobhouse has. Her husband and children will never want for merriment, I vow.”

The squire relaxed a fraction, only partially reassured. “Jolly company is nothing to disparage. A good jest, in its place, is always welcome.”

“I never jest about riding,” Stella said gravely.

“You’ve one of Stockwell’s get, do you not?” Squire Smalljoy asked. “That gray mare with the dappled legs? I’ve seen you riding her about on occasion.”

“Locket,” Stella said. “That’s her name.”

“No idea who the dam is?”

“A half-blood Arabian, I’ve been told.”

He harrumphed. “Could do better in terms of lineage. Still…with Stockwell as her sire, there might be possibilities. A cross with my Irish stallion could produce something worthwhile.”

“I’ve no plans to turn Locket into a broodmare,” Stella said.

The squire helped himself to the last serving of mutton. “Of course, she’ll be a broodmare. What else is she for?”

“What indeed?” Stella murmured. It appeared the squire took the same view of mares that he took of women.

“I’ll have a look at her after dinner,” he said. “If she’s fit for it, you can send her to Castaway Green when the weather clears. She can put up for the spring in my stables until she’s caught.”

Stella’s fingers tightened on her fork. “I’ve already said no, sir. I won’t change my mind.”

The squire turned to Daniel. “Hobhouse. You’re damnably silent. Have you no authority in these matters?”

“It will naturally be as you wish,” Daniel said. “My sister and I would count it an honor for the mare to be sent to you.”

This time, Stella set down her fork entirely. She couldn’t guarantee she wouldn’t use the utensil as a weapon. “Locket belongs to me. The authority over her is, therefore, mine and mine alone.”

Daniel briefly closed his eyes, as if praying for divine patience. “Forgive my sister, sir. She forgets herself. She’s been too long in London.”

“Town ways,” the squire said disparagingly. “Too many years there leaves a taint. Impossible to rub off. A girl forgets her place.”

“Unmarried women do have rights, Squire Smalljoy,” Stella said. “Even if most of the laws are set against us, we are still something, I believe, above mere chattel. We can own property, including horses. We can even string two thoughts together in conversation if we’ve a mind to.”

“Enough, Stella,” Daniel said. “You go too far.”

Squire Smalljoy resumed eating. “Your sister has a sharp tongue, sir.”

“For which I sincerely apologize,” Daniel said. “I blame her health. She’s still overtired from her journey.”

“Frail health as well.” The squire clucked. “Might have guessed it given”—he glanced at Stella’s hair—“all that.”

“Yes,” Stella agreed, offended by his remark to the point of blatant incivility. “I am a questionable specimen. No better a breeding prospect than my mare, I daresay.”

Mrs. Trent gasped in horror.

Amanda lost all color. She sagged in her chair as though she would swoon.

Daniel went as red as a beetroot. “Stella!”

Clamping her mouth shut, Stella returned to her meal. A pit formed in her stomach, making it nearly impossible to swallow down the remainder of her potatoes. She knew that she’d gone too far. She’d been not only uncivil but dangerously indecorous.

Squire Smalljoy took his leave soon after, not even bothering to remain long enough to share a glass of port with Daniel in his book room. Daniel followed the squire from the dining room, apologizing profusely.

Stella remained in her seat, under the molten glare of Mrs. Trent, the possible repercussions of her too-candid words sinking in with a sickening clarity.

How many times these last several months had she had cause to regret her behavior? And yet some small, mutinous part of her soul persisted in pushing her to do too much, to say too much, to take risks she shouldn’t. It had become a habit with her. One that had no more place in Derbyshire than it had in London or Hampshire.

In the past, her lapses had fleeting consequences. But not this time. Whatever happened when her brother returned, Stella had the sickening premonition that, henceforward, her life would never be the same.

Fullepub

Fullepub