Ted

Ted

‘Don’t move. You’ll make it worse.’ Rob’s face is hung above me in the sky. It is even paler than usual.

‘We have to tell someone.’ My beard is wet with tears. ‘I know where she is. Please, please, we have to go now.’ Another good thing about Rob is that he does not waste time on questions.

Everything happens both quickly and slowly. We stagger back to the car, and Rob drives us to a police station. We have to wait there for a long time. I am still bleeding a little but I won’t let Rob take me to a hospital. No, I say, no, no, no, no, NO. As the ‘NO’s get louder Rob backs away, startled. At last a tired man with pouches under his eyes comes out. I tell him what Little Teddy saw. He makes some phone calls.

We wait for someone else to arrive. It is her day off. She hurries in, wearing fishing waders. She has been on her boat. The detective looks very tired and kind of like a possum. I recognise her from when they searched my house, eleven years ago. I am pleased by this. Brain is really coming through for me today! But the possum detective looks less and less tired the longer I talk.

I wait on another plastic chair. Still the police station? No, this is full of hurt people. Hospital. In the end it is my turn, and they staple me up, which is weird. I refuse the painkiller. I want to feel it. So short, this life.

By the time Rob drives me home, it is dawn. As we turn into my street I see a van stopped outside her house. Cars with beautiful red and blue lights, which play on the green trim and the yellow clapboard. The lady is crying and she holds her Chihuahua tight, for comfort. The dog licks her nose. I feel bad for her. She was always nice. Mommy never hurt the Chihuahua lady’s body, but she hurt her all the same.

They put up big white screens around the Chihuahua lady’s house, so that no one can see anything. I stay at the living-room window, watching, even though there is nothing to see. It takes some hours. I guess they have to dig deep. Mommy was thorough. We all stay there, awake and alert in the body, watching the white screens. Little Teddy cries silently.

We know when they bring her out, Little Girl With Popsicle. We feel her as she passes. She is in the air like the scent of rain.

The next-door-neighbour lady has not come back. She was calling the little girl’s name as she ran from me into the woods. That made me think. I told the possum detective about her. When they looked through her house and all her things I felt bad for her – even after everything. It was her turn to have all those eyes on her stuff. Then they found out she was the sister of Little Girl With Popsicle. When I heard, I thought, Now they’re both dead. I felt sure. I don’t know why.

They found Mommy’s yellow cassette tape in the sister’s house. It had her notes on Little Girl With Popsicle. The possum detective says it sounds like she was already dead when Mommy got her. Still, I can’t think about it.

I’m sure Mommy mistook the Little Girl for a boy. Mommy never messed with girls. So Mommy took her because of all those chances coming together. A haircut, a trip to the lake, a wrong turn. It makes my heart hurt and that feeling will never go away, I don’t think. Like a cut that never heals.

The possum detective and I are drinking sodas in my back yard. Our fingers ache after yanking out so many nails. Plywood lies in broken stacks all around us. The house is so strange with its windows uncovered. I keep expecting it to blink. It’s still warm in the sunshine, but cold in the shade. The leaves are thick on the ground, red and orange and brown, all the shades of Rob’s hair. Soon it will be winter. I love winter.

I like the possum detective but I’m not ready to let her in the house. Other people’s eyes make it a place I don’t recognise. She seems to understand that.

‘Do you know where your mother is?’ The possum detective asks the question suddenly, in the middle of another conversation about sea otters (she actually knows a fair amount about them). I smile because I can see that she is enjoying the conversation about sea otters, but also using it to be a detective and try to surprise me into telling her the truth. I like it; that she’s so good at her job. ‘Should I still be looking for her?’ she says. ‘You have to tell me, Ted.’

I think about what to say. She waits, watching.

I don’t know much about the world but I know what would happen if they find the bones. The excavation, the pictures in the newspaper, the TV. Mommy, resurrected. Kids will go to the waterfall at night to scare each other, they’ll tell stories of the murder nurse. Mommy will remain a god.

No. She has to really die this time. And that means be forgotten.

‘She’s gone,’ I say. ‘She’s dead. I promise. That’s all.’

The possum woman looks at me for a long time. ‘Well then,’ she says. ‘We never had this talk.’

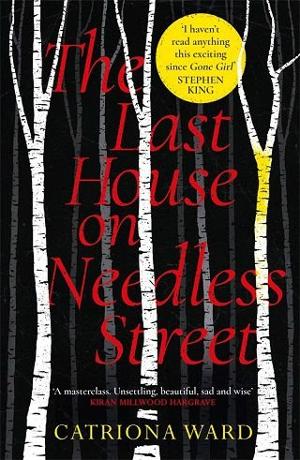

I walk the possum detective to her car. As I’m going back to the house, I notice that the last ‘s’ on the street sign is wearing away. If you squint it might not be there at all. Needles Street. I shiver and go inside quickly.

The bug man is gone. His office is cleared out. I went to see. Now I talk to the bug woman. The young doctor from the hospital fixed me up with her. The bug woman comes to the house sometimes and sometimes I go to her office, which is like the inside of an iceberg, cool and white. It contains a normal amount of chairs. She is very nice and doesn’t look like a bug at all. But I still have trouble with names. And so much has changed. Maybe I need one tiny thing to stay the same.

She suggested that I play back my recordings to see what I have forgotten. I’m surprised to find I’ve used up twelve cassettes. I really didn’t think I recorded that much but that’s why I need the tapes, isn’t it? Because my memory’s so bad.

They’re numbered so I start with 1. The first twenty minutes or so is what I expected. There are a couple recipes, and some stuff about the glade, the lake. Then there’s a pause. I think maybe it’s finished, so I’m reaching over to switch off the recorder, when someone starts breathing into the silence of the tape. In and out. Cold walks up my arms and legs. That’s not my breath.

Then a hesitant, prim voice starts to speak.

I’m busy with my tongue, she says, doing the itchy part of my leg when Ted calls for me. Darn it, this is not a good time.

My heart leaps up into my mouth. It can’t be – oh, but it is. Olivia, my beautiful lost kitten. I never knew she could speak. No wonder I could never find the tape recorder. She sounds sweet, worried and teacher-like. Hearing her is wonderful and sad, like seeing a picture of yourself as a baby. I wish we could have talked. It’s too late now. I listen on and on. I don’t know why I’m crying.

It is called integration, the bug woman tells me. It happens, sometimes, in situations like ours. Integration sounds like something that happens in a factory. I think they just wanted to be together, Olivia and the other one. Anyway, Olivia is gone and she won’t be back.

The bug woman always tells me to let feelings in, not shut them out, so that is what I try to do. It hurts.

There are other voices, among Olivia’s recordings – ones that I don’t know. Some don’t use language, but grunts and long pauses and clicks and high songs. Those are the ones that move through me moaning like cold little ghosts. In the past I tried to shut them in the attic. Now I take time to listen. I’ve spent too long covering my ears.

Dawn wakes me these days. I surface slowly from a dream full of red and yellow feathers. My mind echoes with green sounds and thoughts that are not my own. I can taste blood in my mouth. I never know whose dreams I am going to get in the night. But the body actually gets to rest, these days, instead of being used by someone else while I sleep. So it’s worth it.

Other things are different too. Three days a week I work in the kitchen of a diner across town. I like the walk, watching the city slowly grow up around me. Right now I just wash dishes, but they tell me that maybe soon I can start helping the fry cooks. There is no work today – today is just for us.

Without plywood over the windows, the house seems made of light. I get out of bed, careful not to tear the staples that run down my side. Our body is a landscape, of scars and new wounds both. I stand and for a moment there is a wrestling in the depths of us. The body sways dangerously and we all feel sick. Sulky, Lauren lets me take control. I steady us with a hand on the wall, breathing deeply. The day is full of these seismic, nauseous struggles. We are learning. It is not easy to hold everyone in your heart at once.

Later today, maybe Lauren will take the body. She will ride her bike and draw, or we will go to the woods. Not to the glade, though, or the waterfall. We don’t go there. The blue dress of rotting organza, her old vanity case, her bones – they must be left alone so that they stop being gods and return to being just old things.

We will walk under the trees and listen to the sounds of the forest in autumn.

The tired possum detective and the police are searching the woods near the lake. They want to find the little boys Mommy took. They think there might have been as many as six, over the years. It’s hard to say because children do wander off. They were mostly boys from sad families, or who had no families. Mommy would have chosen the ones who wouldn’t be missed. Little Girl With Popsicle was a big deal because she had parents.

Maybe one day the boys will be found. Until then I hope they are peaceful under the forest green, held by the kind earth.

In the late afternoon perhaps Night Olivia and I will doze on the couch, watching the big trucks. When darkness falls they will hunt. A moment of unease travels through me, like the brush of a wet leaf on the back of my neck. Night Olivia is large and strong.

Well, it’s a beautiful day, and it is breakfast time. As we pass the living room I peer in, and take a moment to admire my new rug. It’s the colour of everything – yellow, green, ochre, magenta, pink. I love it. I could have thrown away that old blue rug any time since Mommy left, I guess. Strange that it never occurred to me until after everything happened.

We go into the kitchen. So far we have only discovered one thing that all of us like to eat. We have it together in the morning, sometimes. I always describe what I’m doing as I do it, so that we all remember. I don’t need to record my recipes any more.

‘We’re going to make it like this,’ I say. ‘Take fresh strawberries from the refrigerator. Wash them in cold running water. Put them in a bowl.’ We watch them gleam in the morning sun. ‘We can dry them with a cloth,’ I say, ‘or we can wait for the sun to do its work. It is our choice.’

I used to saw the strawberries into quarters with a blunt knife, because there was nothing sharp in the house. But now I keep a set of chef’s knives in a block on the counter. ‘This is called trust,’ I say as I slice. ‘Some of us have a lot to learn about it. See my point?’ I guess that is what Lauren calls a dad joke.

The blade reflects the red flesh of the fruit as it slides through. The scent is sweet and earthy. I feel some of them stir with pleasure within. ‘Can you smell that?’ I have to be careful with the knife near my fingers. I don’t give my pain to the others any more. ‘So we slice the strawberries as thin as we can and pour over balsamic vinegar. It should be the kind that is old and thick like syrup. Now we take three leaves from the basil plant that grows in the pot on the window ledge. We slice these into narrow ribbons and breathe the scent. Now add the basil to the strawberries and balsamic vinegar.’ It is a recipe, but sometimes it sounds like a spell.

We let it sit for a few minutes, so the flavours can mingle. We use this time to think, or watch the sky, or just be ourselves.

When I feel it’s ready I say, ‘I’m putting the strawberry, basil and balsamic mixture on a slice of bread.’ The bread smells brown and nutty. ‘I grind black pepper over. It’s time to go outside.’

The sky and trees are flooded with birds. The song flows and ebbs around us, on the air. Lauren gives a little sigh as the sun warms our skin.

‘Now,’ I say. ‘We eat.’

Fullepub

Fullepub