Chapter Eleven

August 9, 1810

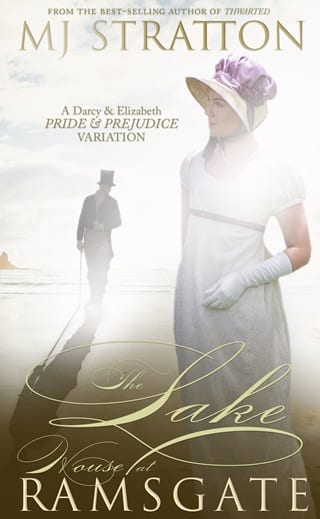

The Lake House

Ramsgate

Darcy

Waiting for a reply from Miss Bennet— Elizabeth— was interminable. Pretending she was now anything but ‘Elizabeth’ to him tested Darcy’s patience in a way few other things did. There was no discernible pattern as to how long letters took to pass from 1810 to 1812, though it seemed to vary depending on the writer. From the dates on many of Elizabeth’s replies, Darcy gathered that sometimes as little as a day passed before his letters traversed time to its destination.

His preoccupation had become apparent to Georgiana, and he had caught the speculative looks she cast his way. Oh, if only he could confide in her! But such a tale was beyond belief, and he could not expect her to accept it. Her current disillusionment with the superficial young ladies of society would surely increase her suspicions.

There was nothing for it—he must immerse himself in his work and the care of Georgiana, lest his thoughts drive him mad. At last, four days after sending his last letter, another arrived.

August 8, 1812

Dear Sir,

Pray forgive the delay in my reply. How absurd that sounds, when regular post would take far longer to arrive than our letters do. I began crafting my response as soon as I received your letter, but a number of tasks and troubles kept me from completing it until now.

Your flattering words regarding my appearance, sir, have touched me, though I must inform you that, according to my mother, I am only the fourth most beautiful Bennet daughter. Jane holds the highest place in her esteem. My sister Lydia follows next, being the liveliest and most like Mama herself. Kitty naturally follows, for she mirrors Lydia’s behaviour as she seeks Mama’s approval. I am deemed tolerable. Mama says that I am too brown from being in the sun and that my lack of ladylike accomplishments will deter many suitors. However, she considers poor Mary the least attractive of the Bennet girls—not to say that she is plain, but merely unremarkable by comparison.

Nevertheless, your kind words soothed my soul and give me hope that I may yet prove tolerable enough to tempt a gentleman into matrimony.

Your parents sound truly wonderful. I have often wished that mine shared such affection as yours did. I have spoken of Mr and Mrs Bennet before, so I shall not revisit those sentiments. How fortunate you are to have grown up surrounded by such felicity. It seems odd to me that, having witnessed the happiness of your parents, you would ever consider marrying for anything less. Yet, such is the way of the first circles.

Your father’s death must have placed a heavy burden upon your shoulders. From our earlier letters, I have surmised that you were very young when you lost him. My father did not inherit Longbourn until he was three-and-thirty, which was after I was born. I do not think he would have proven as adept at managing Longbourn had he assumed control of the estate before gaining his majority. As it is, he shows little interest in its management, and I cannot imagine that would have changed had he inherited at a younger age.

I cannot fathom the pain your mother and grandmother must have endured since I am not married, and my mama had no such troubles. Five daughters in less than eight years! If only she had borne a son, her happiness would have been complete. Your early years must have been terribly lonely until your sister arrived. I am glad, for your sake, that you have her with you.

What caused your marital perspectives to change, if I may ask? Mine have always been steadfast, shaped by the turbulent family in which I was raised. I was sixteen before I fully grasped that my father’s words to my mother held more than simple meaning, and older still before I understood the sharpness of his remarks. Mama’s fretting was once less pronounced, but my father’s continual belittling has done nothing to ease the situation. Perhaps her nerves might improve if he would guide her as a husband ought, rather than leaving her to flounder alone.

My mother is, I believe, content with her lot. Her status was elevated upon marrying my father. Although she is the great-granddaughter of a landed gentleman, her family has long since fallen from the ranks of the gentry. Her father, my Grandfather Gardiner, was a prominent solicitor in Meryton, and upon his passing, his business was willed to my uncle, Mr Andrew Phillips, who is married to my mother’s sister, Harriet. Mother’s brother, Mr Edward Gardiner, resides in London with his wife, the former Madeline Partridge.

The Gardiners live on Gracechurch Street near Cheapside, within sight of my uncle’s warehouses. He owns a successful import and export business, and I suspect he earns more per annum than my father does from his estate.

Despise me if you dare, Mr Darcy, for my connexions. Though not as elevated as your own, my relations are dear to me. I hold deep affection for my Aunt and Uncle Gardiner. As I have mentioned, it is through their tender care that Jane and I have not become as wild as my younger sisters. From the age of thirteen, we spent several months each year in London under their guidance. Aunt Gardiner’s instruction taught Jane and me the proper way to behave, and her influence is evident to all who know us.

I recall one such venture into town. It was in October of 1810, and I was nine-and-ten. My aunt had promised to give me a taste of London society. Jane accompanied me, and we eagerly anticipated spending the Little Season attending balls, soirees, and parties every night. That time is so memorable because, whilst we were in town, we heard that King George III had been officially declared insane, and his son, the Prince Regent, would assume control of the kingdom. But I digress.

After only a short time attending events, I found myself weary of the constant revelry. My aunt eyed me knowingly when I confessed this; whilst I do enjoy society, too much of it leaves me longing for peace and quiet. Thus, she took me to Hatchard’s to choose a book. I was in search of a specific volume for myself and another for my father’s birthday. I had but little time to find the ideal present, as his birthday was just three days away.

My dear aunt kindly spared time from her busy day to escort me about Town. She waited patiently as I browsed the volumes and did not so much as bat an eye when an unknown gentleman assisted me in selecting the perfect gift. She did, however, remind me of proper decorum on our return in the carriage! I shall forever be grateful for her gentle guidance—so different from Mama’s scolding or Papa’s indifference.

I know not if this memory conveys how dear my relations are to me, but there you have it. Now, on to Mr Blandishman, though I cannot agree that he is tantalising!

You are correct—Mama knows nothing of him. I made Jane swear to keep his visits a secret. I am not certain if one would call his attentions courting, precisely, though he calls on my brother twice a week.

Mr Blandishman is… unremarkable. He is of average height and build, with sandy brown hair and brown eyes. His mannerisms remind me of our favourite parson in Kent, though he lacks some of my cousin’s more intolerable traits. His situation is favourable for a woman in my position, and should he offer a proposal, it would be folly to refuse him. You know well how Mr Collins fared, however, and can likely guess what course I shall take if I find that I cannot love him.

I wish you success in your search for a companion for your sister. Were I in your place, I would send inquiries ahead, so that when you arrive in town, you have prospective ladies ready for consideration. The position of a lady’s companion is a coveted one, and such a woman holds great influence over her charge. She may either assist or hinder Miss Darcy’s introduction to society, so only the most suitable candidate will do, especially when it comes to facing the harpies of the ton .

Regarding your proposed meeting, I shall make a note of it in my journal. Tomorrow, I intend to venture out in search of this magnificent establishment you described, for I absolutely refuse to wait until next spring to sample the pastries and teas you so highly recommend.

Mr Darcy, since writing the above, I have attended a dinner with my brother and sister and have learned something that may interest you.

We dined at the home of Mr and Mrs Nelson, a young and cheerful couple my brother-in-law has recently befriended. They have only lived in Ramsgate for six months or so. Mrs Nelson would get along famously with my mother, for she delights in gossiping about everyone and everything.

Tonight’s topic of discussion was, surprisingly enough, the Lake House. Mrs Nelson claims to have it on good authority that the house has stood empty since last summer, though it has remained fully staffed. She expressed surprise that Jane would wish to stay in a house so marked by tragedy. When I pressed her for details, she admitted she knew little—only that something occurred last summer which drove the owners from Ramsgate, never to return.

Her account was rather dramatic, but if there is any truth in her words, something did indeed happen last year—next year for you—that will lead you to lease the house this year, in 1812. I shall keep my ears open for more information, though it seems the family kept the entire affair quiet, and no one truly knows what transpired.

Goodbye for now, Mr Darcy. I look forward to your next letter.

Yours,

E. Bennet

Darcy waited for the usual feelings of disgust and aversion to arise at the news of Elizabeth’s connexions, but none came. Had his opinions shifted so significantly that the thought of a tradesman for an uncle no longer troubled him? Even more surprising was the jealousy that surged within him as he read of Mr Blandishman—so strong, in fact, that it had caused him to wrinkle her letter. That gentleman was all… wrong for her. He would have to tell her so. She claimed there was no understanding, no courtship, but why else would the man persist in calling at the Lake House if not to see Elizabeth? He could not believe it was only her brother that drew him there.

Yet what intrigued him most was her signature. How I wish you were mine, he thought, retrieving her likeness from his coat pocket—it was there most days now, for he could not bear to part with it even for a moment. He gazed at her face once more, a soft smile forming on his lips.

His thoughts returned to her letter. She had agreed to meet him! Now came the waiting. It would be difficult, but he would endure it. Her letter had sparked another idea; another opportunity to see her in person. He would be unable to do more than observe her from afar, but it was something.

As for the tittle-tattle this Mrs Nelson had related… what could have possibly happened? Surely, if the Darcy family had been involved in any tragedy, the gossips would have widely talked of it in Ramsgate and in Town. Why was there so little information? Darcy considered asking Elizabeth to enquire further, but her source seemed to have reached the limits of her knowledge. It was of no matter. Darcy would simply prepare for the worst and prevent it from happening—or, at the very least, he would be vigilant, for he had no way of knowing exactly what this ‘tragedy’ could entail.

For now, he was content. Elizabeth’s letter had given him enough to ease his mind, and he was better able to focus on his work and on Georgiana. His sister brightened considerably after they spent a day together, and Darcy resolved to give her more attention during their remaining weeks in Ramsgate. He must temper his desire to communicate with Elizabeth; his lack of self-control should not cause Georgiana to suffer. There was nothing he could do to hasten the arrival of letters, and he would have to be satisfied to receive them whenever they came.

His commitment to Georgiana delayed his reply to Elizabeth’s letter by several days. Thus, it was mid-August before he sanded, sealed, and placed his response on the salver.

Fullepub

Fullepub